This was supposed to be a completely different write-up.

I originally intended to publish a sort of "Name and Shame" on some of the biggest tech companies in Silicon Valley. Screenshots of the sites you use daily, all vulnerable to the three of us hijacking your session and doing whatever the fuck we wanted with it.

Unfortunately, as it turns out, the only thing faster than an XSS payload is a veiled legal threat.

At the start of this week, as our disclosure planning was coming to a close, several companies decided to engage in some very aggressive PR management. Because, of course, the last thing a C-Suite wants to sign off on before Q4 earnings — and more importantly, just before Christmas break (happy holidays in advance!) — is Item 1.05 of a Form 8-K.

For those unfa…

This was supposed to be a completely different write-up.

I originally intended to publish a sort of "Name and Shame" on some of the biggest tech companies in Silicon Valley. Screenshots of the sites you use daily, all vulnerable to the three of us hijacking your session and doing whatever the fuck we wanted with it.

Unfortunately, as it turns out, the only thing faster than an XSS payload is a veiled legal threat.

At the start of this week, as our disclosure planning was coming to a close, several companies decided to engage in some very aggressive PR management. Because, of course, the last thing a C-Suite wants to sign off on before Q4 earnings — and more importantly, just before Christmas break (happy holidays in advance!) — is Item 1.05 of a Form 8-K.

For those unfamiliar, that is the specific securities form where you tell your shareholders that your stock price might be affected by a "Material Cybersecurity Incident".

Oh well, names are gone and the details are anonymized, but since the lessons are universal anyways; here’s an overview of what we observed throughout our Fortune 500 audit.

The Overview

We didn’t audit Mintlify’s entire customer list just to pop alert(document.domain).

I’m pretty sure at some point I’d be blocked from HackerOne/Bugcrowd submissions for spam if I kept sending reports for that alone.

We did it because the difference between "P4/Informative" and "P1/Critical" isn’t just the vendor code itself, it’s how much you trust third-party services in general.

The results? Not surprising at all, a healthy mix between customers that treated third-party vendors with zero-trust paranoia, and others that — quite literally — used configurations that were functionally equivalent to granting an all-access admin token.

Implicit Trust

This was the configuration we observed the most among companies that likely prioritized great UX over not getting pwned. They treated a third-party service as if it were their own product, rather than a regular dependency susceptible to compromise.

In these environments, the end result went from simple pop-up, to a whole ’nother chain of issues.

1. Wide CORS policies

The first failure usually started innocently enough. You run a documentation portal, and you want those cool "Try it now!" buttons that let developers test API requests directly from the browser. To make that happen, your backend needs to allow requests from the docs site.

So, the server is configured to respond with:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://docs.company.com

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

To the dismay of every UX designer who dreamt this up: You don’t own that subdomain. The vendor running code on it does. Whitelisting them defeats the entire purpose of the Same-Origin Policy, even if you think it’s "necessary" for that one cool feature (it isn’t).

2. Session Management? Isolation? What’s that?

This is where bad web design should probably be classified as a form of securities fraud.

In the first instance (CORS), the only "tokens" at risk are specific API keys you may have setup. That’s bad, but not "I guess I don’t own my account anymore" bad.

Unless... you scope your authentication cookies to the entire wildcard domain.

For the sake of smooth SSO between Support portals, Developer hubs, and the Main application itself, these companies often decided to share a single Session ID across the entire *.company.com namespace via:

Domain: .company.tld

Functionally, this renders SameSite protections completely useless.

Because the browser treats docs.company.com and api.company.com as the "Same Site" (sharing the eTLD+1), even SameSite=Strict will not save you. The browser sees where the request is coming from and just attaches the credentials automatically.

Worst of all? Almost none of the companies who did this even bothered setting HttpOnly, meaning we didn’t have to ride the session, we could just take the whole damn cookie jar.

Once again: UX > Security.

3. It’s just documentation...

The last issue wasn’t about what was configured wrong, but what wasn’t configured at all: Content Security Policy I mean, it’s just static content and SVGs, who cares if it even has a CSP?

One of the specific exploits relied on loading the SVG as an executable <object> or <iframe> to either trigger the script, or using those same HTML tags to widen the exploit chain itself. A single Content-Security-Policy: object-src 'none' would have neutralized this entirely. It doesn’t even break legitimate images, since you’d just use <img>.

The documentation pretty much became an execution environment, and I can’t even begin to think of a reason as to why that was necessary.

Explicit Distrust

On the other end of the spectrum, we saw companies with complete immunity to any attempts at escalating the initial XSS — and in some cases (like with the above CSP), even to the XSS itself.

A simple philosophy of "Third-party services will eventually get hacked".

1. TLD Isolation

The best defense we saw, whether it was intentional or not, was complete domain separation. Instead of hosting documentation at docs.company.com, or even company.com/docs, the engineering teams behind them used entirely separate Top-Level Domains (e.g., company.tld2).

This in return, completely mitigates any sort of site misconfiguration you could possibly have on the documentation site, from affecting the main app.

2. Host-Only Scoping

Where subdomains were necessary, companies properly scoped their cookies strictly to the app host itself (e.g., app.company.com). This was often the case with companies that used company.com as just the home/marketing pages, with the actual main app being behind said subdomain.

This in return, ensured that credentials could never "bubble up" to other parts of the site.

Even if we had JS execution on docs.company.com, regardless of other negligent configurations, the (authentication) cookies were only visible to app.company.com.

In the grand scheme of things, we would achieve at most JS execution on their documentation, but were otherwise completely isolated from the actual users themselves.

Bonus

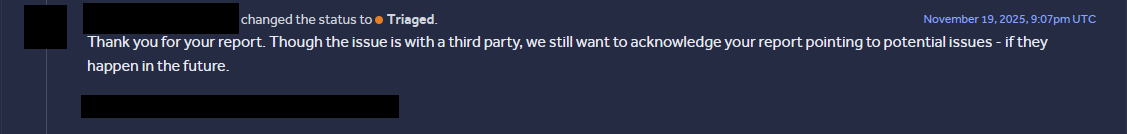

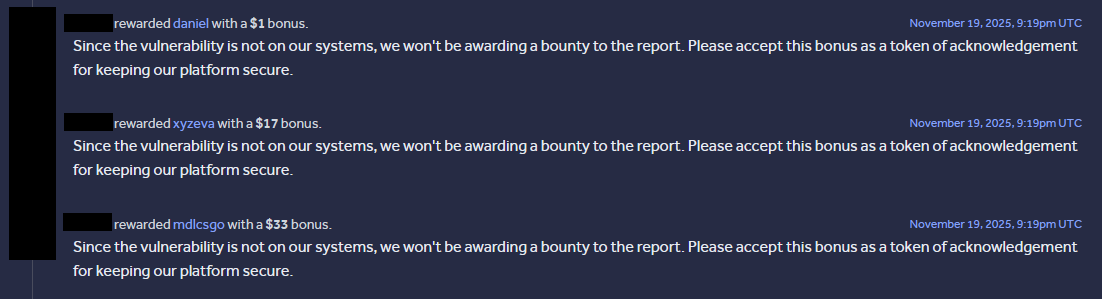

As a bonus for making it this far, here’s what one company valued at "$44 billion" had to say about us reporting some of their misconfigurations (the exact three named above!) that led to the full chain!

Don’t be like that company.

Final Thoughts

This was (unfortunately) my first write-up. While the "Hall of Shame" will never see the light of day, I hope this write-up series (go check out eva and Daniel!) managed to highlight exactly what goes wrong when you treat a dependency like a first-party product.

Honestly, throughout all the companies we tested for this, I was pleasantly surprised by how many ended up mitigating any real threat from this 0-day simply via good architecture. It gives me hope that despite the rapid Silicon Valley adoption of "move-fast-and-break-things" AI startups, good engineering can still protect users from rookie mistakes that inevitably occur to... well, rookies.

Shoutouts to Discord, Vercel, and Cursor as well for handling the disclosure process properly, without involving PR management.

Lastly, a huge shoutout to the Mintlify team as well for their coordination and assistance throughout the last month. After we first discovered the XSS and eva reported the RCE, they were super cooperative in getting any remaining issues addressed and even went as far as giving us snippets of source code to assist. They handled this last month a lot better than most other companies would have, and were very helpful in ensuring these write-ups remained transparent and accurate.

To any Mintlify customers who want to have their name included (or send legal threats/cease and desists, that works too), you can send them to legal@heartbreak.ing

For everyone else who has any questions or words of wisdom/feedback, feel free to reach me at contact@heartbreak.ing

Enjoy the holidays! May your pagers remain silent, and your production environment stay at 100% uptime.

Happy New Year :)