In the last post, I hit the “send” on my v1 patch series. It was a huge milestone!

But as I said last time, that wasn’t the end. It was the beginning of a whole new stage: the review process.

This is the part of the kernel development story that’s both thrilling and humbling. Seeing replies from experienced maintainers in your inbox is a rush. Their feedback is a roadmap to making your code not just work, but be correct—and there’s a world of difference.

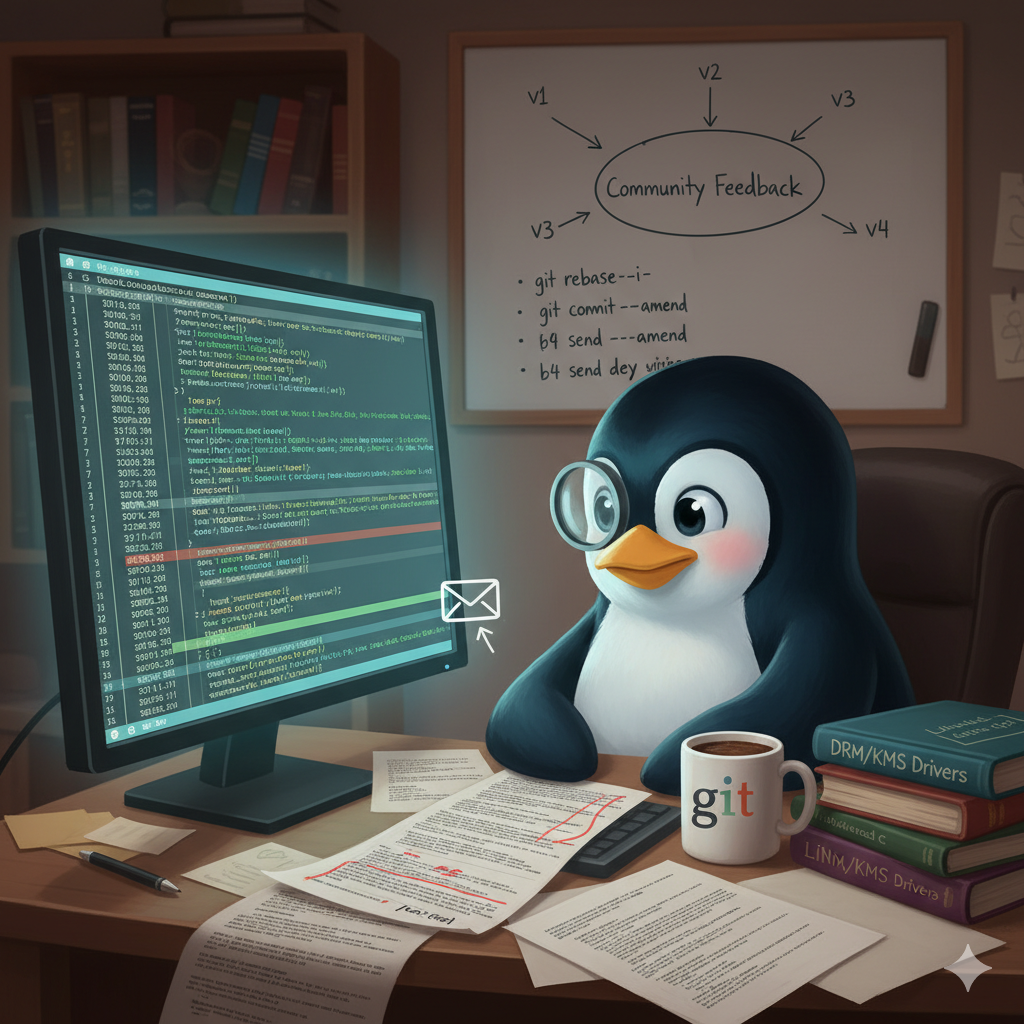

It was time to roll up my sleeves, fire up git, and get to work on v2 (and v3, v4, v5, v6 and v7).

The roolkit: rebase and amend

My new best friends for this phase weren’t b4 prep (not yet), but the bread-and-butter of Git history management: Bash

`…

In the last post, I hit the “send” on my v1 patch series. It was a huge milestone!

But as I said last time, that wasn’t the end. It was the beginning of a whole new stage: the review process.

This is the part of the kernel development story that’s both thrilling and humbling. Seeing replies from experienced maintainers in your inbox is a rush. Their feedback is a roadmap to making your code not just work, but be correct—and there’s a world of difference.

It was time to roll up my sleeves, fire up git, and get to work on v2 (and v3, v4, v5, v6 and v7).

The roolkit: rebase and amend

My new best friends for this phase weren’t b4 prep (not yet), but the bread-and-butter of Git history management: Bash

git rebase -i

git commit --amend

The rebase -i (interactive rebase) was crucial for squashing fixes into the right commits, and amend was perfect for polishing the commit messages. Once the code was updated, I turned back to my new favorite tool, b4, to package and send the new version.

b4 prep --edit-cover

b4 prep --check

b4 send --no-sign

This cycle became my rhythm. And what a cycle it was. Here’s a breakdown of the journey from v1 to v7.

Changes in v2: the great refactor

The v2 feedback was substantial. The reviewers pointed out some core structural issues, and fixing them made the driver so much cleaner.

SPI communication: the feedback pushed me to internalize all the error handling and delays inside the st7920_spi_write() helper. No more scattering msleep() calls in the main logic. I also split the main write function into smaller, command-specific helpers, which made everything far more readable.

DRM/KMS logic: This was a big one. I had CPU access calls (drm_gem_fb…) in the wrong place. Following the feedback, I moved them to the atomic_update hook where they belong. I also changed my custom validation to standard DRM helpers, which is always the most appropriate choice.

Cleanup: I got to delete dead code (goodbye, ST7920_FAMILY!), replace WARN_ON() with the more appropriate drm_WARN_ON_ONCE(), and fix my probe initialization order.

Changes in v3: polishing the details

Version 3 was all about correctness and polish.

Patch organization: a great tip I got was to document the Devicetree bindings before they are used. I reorganized the patch series to do just that.

Error handling: I’d missed an error path! I implemented the reviewer’s suggestion to use a goto label to ensure drm_dev_exit() is always called, even when drm_gem_fb_begin_cpu_access() fails.

Changes in v4: mastering the hardware

I thought v3 was good, but the v4 feedback showed me I still had more to learn about the hardware and the DRM subsystem.

Datasheet deep dive: the reviewers were right, I was missing minimum hardware requirements from the datasheet. I added definitions for the VDD power supply and the XRESET GPIO line.

Error handling refactor: the error handling strategy has been refactored to propagate an error-tracking struct from the caller.

DRM atomic logic: I had put my atomic_enable and atomic_disable logic in drm_encoder_helper_funcs. A reviewer correctly pointed out this functionality is bound to the CRTC, so I moved it all to drm_crtc_helper_funcs and added the proper drm_dev_enter() / drm_dev_exit() calls to manage the device’s power state.

General cleanup: renamed macro definitions to match the correct terminology.

Changes in v5, v6 and v7: stabilizing the driver

DRM compliance: renamed macros to avoid the reserved DRM_ prefix and switched to standard DRM logging helpers.

Atomic KMS logic: the atomic state duplication now uses kzalloc instead of kmemdup, and the atomic update function was refactored to integrate CPU access within the damage loop.

Hardware control: GPIO reset logic was fixed to respect logical levels, and I removed unused device variant structures to simplify the resolution handling.

Fix warnings from checkpatch.pl.

Remove unused DRIVER_DATE.

If you are wondering what the applied patch version looks like, here is the link.

Side quest: improving the foundation

This review process wasn’t just about my driver. It was about learning the “right” way to do things. I had based my work on the solomon ssd130x driver, and I realized that some of the lessons I learned could be applied there, too.

So, I took a small detour, put together a patch with some cleanups for the ssd130x and sent it upstream. It felt great to not only contribute my new driver but also to pay it forward and improve the code I had learned from.

Conclusion

It has been a long journey, but it’s been very rewarding. I’ve always wanted to contribute to the Linux kernel and this has been my best experience so far. I’ve created a driver from scratch, tested it and send it for review. I am very proud to have achieved this, and I hope that this is not just the end of something, but the beginning of a long history of contributions.

If you’ve made it this far and read all the posts in this series, thank you very much for joining me on this journey. I’ve been thrilled to share it with you, and I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed sharing it.