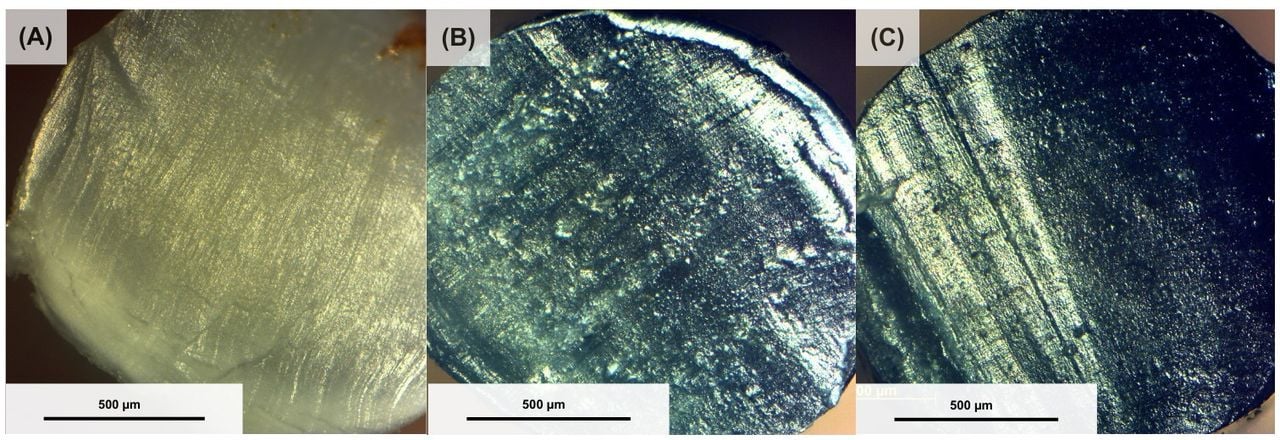

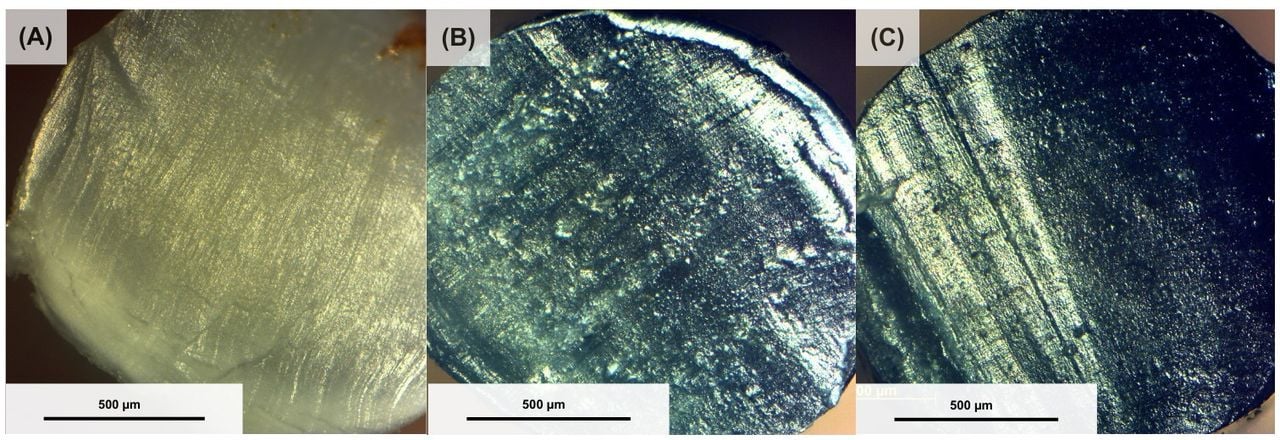

PEDOT same 3D prints [Source: University of Kentucky]

PEDOT same 3D prints [Source: University of Kentucky]

A new dissertation explores fiber-based conductors and 3D printed PEDOT for wearable and soft electronics.

The document, titled “Functional Fiber-Based and 3D-Printed PEDOT,” focuses on poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) — better known as PEDOT — a workhorse conductive polymer frequently blended as PEDOT:PSS (polystyrene sulfonate) for waterborne processing. While metals still dominate functional AM, PEDOT systems bring stretchability, low-temperature processing, and textile compatibility, which are valuable in biosignal electrodes, strain sensors, and soft robotic skins.

Most AM readers know the tradeoffs: metal-filled FFF filaments and carbon-lo…

PEDOT same 3D prints [Source: University of Kentucky]

PEDOT same 3D prints [Source: University of Kentucky]

A new dissertation explores fiber-based conductors and 3D printed PEDOT for wearable and soft electronics.

The document, titled “Functional Fiber-Based and 3D-Printed PEDOT,” focuses on poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) — better known as PEDOT — a workhorse conductive polymer frequently blended as PEDOT:PSS (polystyrene sulfonate) for waterborne processing. While metals still dominate functional AM, PEDOT systems bring stretchability, low-temperature processing, and textile compatibility, which are valuable in biosignal electrodes, strain sensors, and soft robotic skins.

Most AM readers know the tradeoffs: metal-filled FFF filaments and carbon-loaded resins print easily but rarely reach useful conductivity for demanding wearables without sacrificing flexibility. Conductive polymer networks take a different path, leveraging percolated polymer domains and secondary dopants to boost carrier mobility, often at lower temperatures than metals require. A fiber-first approach also fits the realities of garment manufacturing, where yarns and narrow tapes integrate better than rigid islands on fabric.

Why PEDOT, And Why Now

PEDOT:PSS has long been used as a transparent electrode and antistatic coating, but translating it into mechanically robust, patterned, and thick structures remains a challenge. The dissertation’s framing signals a push past thin films toward functional fibers and printed 3D geometries that can survive bending, stretching, and repeated cycles. In AM terms, that means inks with shear-thinning rheology for Direct Ink Writing (DIW) or jettable fluids for inkjet, plus adhesion strategies for textiles and elastomers.

What makes this interesting for AM is the potential to combine pattern freedom with softness. Directly writing conductive tracks onto fabrics or printing freestanding PEDOT features could reduce assembly steps and avoid harsh sintering. Because PEDOT systems can be processed from water, they also align with benchtop labs and educational makerspaces that avoid solvent-heavy workflows.

From Fibers To Printed Architectures

Although the abstract is not provided, work of this kind typically targets two fronts. The first is fiber-based conductors via coating, wet spinning, or dip-drawing, which are then plied into textiles or routed like flexible leads. The second is 3D printed features — serpentine interconnects, contact pads, or sensor bodies — deposited by DIW onto fabrics, elastomers, or temporary release layers, followed by drying and mild anneal. Reported conductivities in the literature for optimized PEDOT:PSS vary widely, often landing between tens to low thousands of S/cm after secondary doping and thermal treatment, but the specific values here are not stated.

Conductive polymers can be humidity sensitive, their conductivity can drift with strain, and adhesion to low-surface-energy textiles is not guaranteed without primers or surface activation. Post-processing usually includes controlled drying and dopant exchange, which can affect throughput. Feature sizes achievable by DIW are coarse compared to photolithography, and printing onto stretch fabrics introduces registration and warping challenges that demand closed-loop deposition or clever fixturing.

If the inks demonstrate stable resistance over thousands of strain cycles, compatibility with common laundry conditions, and reliable contact resistance at terminations, the path to application is clearer. Service bureaus focused on wearables, research labs building instrumentation, and medical device teams prototyping skin electrodes could all benefit from printable, soft conductors that do not require metal pastes or high-temperature sintering.

Economically, this approach trades raw conductivity for lower process temperatures, fewer rigid interposers, and potentially less manual assembly. A DIW toolhead on an existing motion platform can pattern circuits post-cut-and-sew, which shrinks touch time compared to sewing conductive threads by hand. Unknowns remain around ink shelf life, multi-material registration with elastomeric substrates, and whether the process can meet the repeatability targets of contract textile manufacturing.

What To Watch In Validation

Key data to look for include conductivity versus strain curves, cycle endurance to at least five or six figures, wash and abrasion durability, and biopotential electrode impedance on skin. Print resolution, layer adhesion in stacked structures, and the effect of humidity on resistance drift would also clarify real-world performance. If the dissertation releases ink formulations or processing windows, that will accelerate replication across labs and service shops.

The larger takeaway is that conductive polymers are inching from coatings toward structural, printed elements that align with AM’s strengths in geometry and on-demand production. If this work can prove consistent, textile-ready performance, expect more DIW toolpaths to land on fabric rather than metal build plates.