By Ankit Mittal on January 21, 2026

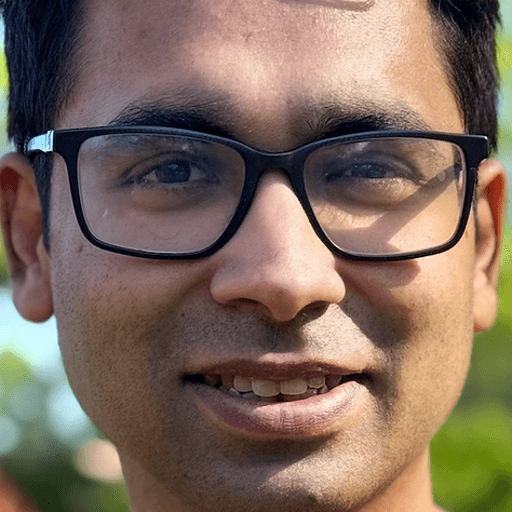

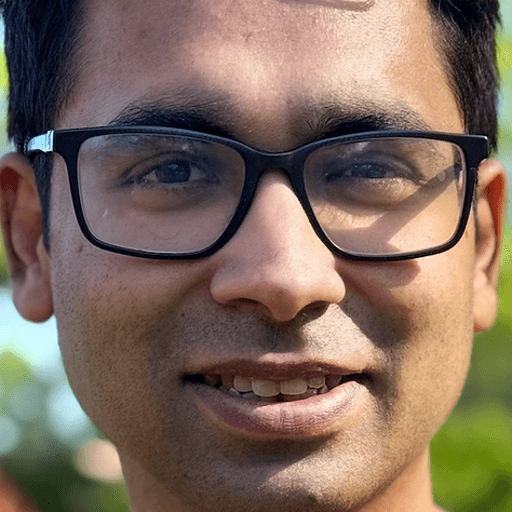

When I search for "King", I’m looking for LOTR - The Return of the King. You might be looking for The King’s Speech. A generic search engine returns the same results for both of us, likely a mix of Fantasy and Drama, which means it fails both of us.

I first presented a solution to this shortcoming at [PGConf NYC 2023](https://postgresql.us/events/pgconfnyc2023/schedule/s…

By Ankit Mittal on January 21, 2026

When I search for "King", I’m looking for LOTR - The Return of the King. You might be looking for The King’s Speech. A generic search engine returns the same results for both of us, likely a mix of Fantasy and Drama, which means it fails both of us.

I first presented a solution to this shortcoming at PGConf NYC 2023. Having engineered search infrastructure systems at Instacart, I’ve seen firsthand how complex search systems crumble under their own weight. Similar patterns power search at giants like Target and Alibaba.

Personalization can take a "good enough" search experience to a magical one. Traditionally, building personalized search involved a complex Rube Goldberg machine: syncing data to Elasticsearch, building a separate ML recommendation service, dragging data to Python workers for re-ranking, then stitching it all back together. It works, but the cost is high: architectural complexity, network latency, and data synchronization nightmares.

What if you could build a production-grade personalized search engine entirely within Postgres? No new infrastructure. No network hops. Just SQL.

In this post, we’ll build a personalized movie search engine using just Postgres, with ParadeDB installed. We’ll implement a "Retrieve and Rerank" pipeline that combines the speed of BM25 full-text search with the intelligence of vector-based personalization, all without the data ever leaving PostgreSQL.

This post is based on a functional prototype concept I created which demonstrates in-database personalization patterns. If you’re the type who reads the last page of a novel first, feel free to start there.

The Architecture: Retrieve & Rerank

The Retrieve and Rerank approach breaks the problem into two stages, utilizing the strengths of different algorithms:

- Retrieval: We use BM25 (standard full-text search) for lexical search to find the top N candidates (100 here) matching the user’s query. This is extremely fast and computationally cheap, filtering millions of rows down to a relevant subset.

- Reranking: We use Cosine Similarity and semantic / vector search to re-rank those 100 candidates ordering them based on the user’s personal profile.

Why this approach? Because running vector similarity search on your entire dataset for every query is overkill. For n=100n=100 items (or even 1000), it would be better to ignore vector indexes, and instead brute force our way to a result.

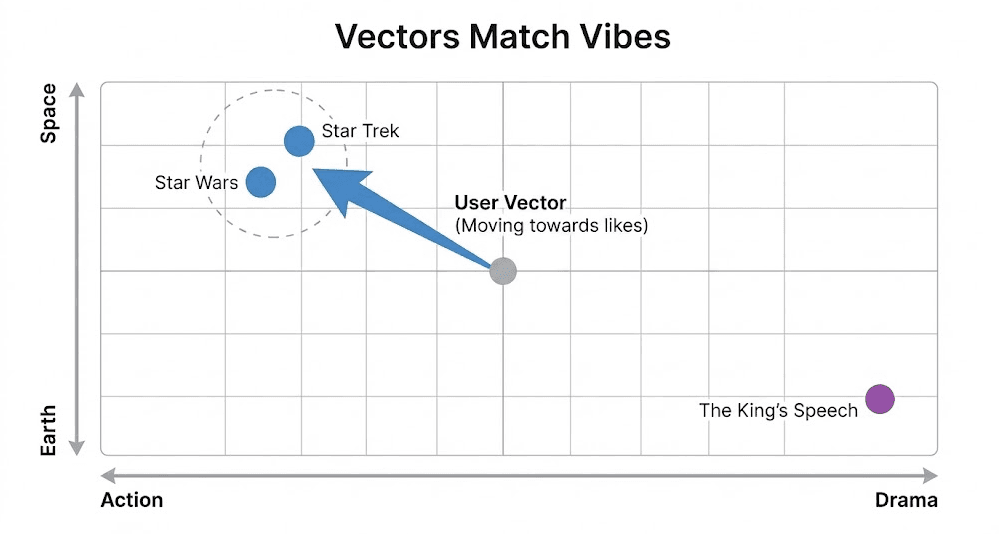

The Intuition: Vectors Match Vibes

Before we look at code, it helps to understand why this works.

Traditional search matches keywords. If you search for "King", a keyword engine simply looks for the string "King" in titles. It returns The Return of the King, The King’s Speech, and The Lion King with equal confidence, but it has no way to know which one you want.

A User Vector represents aggregated taste. It can be built from explicit signals (like the 5-star ratings we look at in this post) or implicit signals (like clickstream data or watch time).

In our example, if a user dislikes The King’s Speech but loves Star Wars, we steer their vector towards fantasy and away from drama in the embedding space.

Implementation

Let’s build it. We need two core entities: Movies (the content) and Users (the personalization context).

1. Core Schema

We use standard Postgres tables for movies and users, plus a ratings table for likes and dislikes.

Personalization requires user-specific signals. Here we use explicit ratings: 4-5 stars signals a like, 1-2 stars signals a dislike. You could also use implicit signals like watch time or click behavior.

-- Enable required extensions

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pg_search;

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS vector;

-- The content we want to search

CREATE TABLE movies (

movie_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY,

title VARCHAR(500) NOT NULL,

year SMALLINT,

genres TEXT[],

imdb_id VARCHAR(20),

tmdb_id INTEGER,

-- Embedding representing the movie's semantic content

-- (e.g. from OpenRouter/HuggingFace)

-- We used all-MiniLM-L12-v2 which has 384 dims

content_embedding vector(384),

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT now()

);

-- The user profiles

CREATE TABLE users (

user_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

-- A vector representing the user's taste

embedding vector(384)

);

Movies get a ParadeDB BM25 index.

CREATE INDEX movies_search_idx ON movies

USING bm25 (movie_id, title, year, imdb_id, tmdb_id, genres)

WITH (key_field='movie_id');

We use pgvector’s vector column to store movie and users embeddings. Movie embeddings can be created by calling OpenRouter or Huggingface APIs. For the demo we used sentence-transformers/all-minilm-l12-v2 model.

2. Generating User Profiles

How do we get a vector that represents a user’s taste? In a complex stack, you’d have a background worker processing datastreams in Python. We can do that too, but since all our movie embeddings are already in Postgres, we can use standard SQL aggregation to get user embeddings.

-- Generate a user's profile vector:

-- Move towards movies they like (>= 4 stars)

-- Move AWAY from movies they dislike (< 3 stars)

UPDATE users SET embedding = (

SELECT SUM(

CASE

WHEN r.rating >= 4.0 THEN m.content_embedding

ELSE m.content_embedding * -1

END

)

FROM ratings r

JOIN movies m ON r.movie_id = m.movie_id

WHERE r.user_id = users.user_id

AND (r.rating >= 4.0 OR r.rating < 3.0) -- Ignore mediocre ratings

);

This is the power of "In-Database AI". You don’t need a separate pipeline to keep user profiles up to date. You can update them transactionally as ratings come in.

3. The Unified Search and Recommender Engine

Now for the main event. We can execute the entire Retrieve & Rerank pipeline in a single SQL query using Common Table Expressions (CTEs).

Instead of a black box, let’s break this down into four logical steps: Retrieve, Normalize, Personalize, and Fuse.

Step 1: The Retrieval (Fast)

First, we use BM25 to find the top 100 candidates. This is our "coarse filter" that casts a wide net to find anything relevant to the text query.

WITH first_pass_retrieval AS (

SELECT

movie_id,

title,

paradedb.score(movie_id) as bm25_score

FROM movies

WHERE title @@@ 'action'

ORDER BY bm25_score DESC

LIMIT 100

),

Step 2: The Normalization (Math)

BM25 scores are unbounded (they can be 10.5 or 100.2), while Vector Cosine Similarity is always between -1 and 1. To combine them fairly, we normalize the BM25 scores to a 0-1 range using a standard Min-Max scaler.

normalization AS (

SELECT

*,

(bm25_score - MIN(bm25_score) OVER()) /

NULLIF(MAX(bm25_score) OVER() - MIN(bm25_score) OVER(), 0) as normalized_bm25

FROM first_pass_retrieval

),

Step 3: The Personalization (Smart)

Now we bring in the user context. We calculate the similarity between our normalized candidates and the current user’s taste profile.

personalized_ranking AS (

SELECT

n.movie_id,

n.title,

n.normalized_bm25,

-- Cosine similarity: 1 - cosine_distance transforms distance to a 0-1 similarity score

(1 - (u.embedding <=> m.content_embedding)) as personal_score

FROM normalization n

JOIN movies m ON n.movie_id = m.movie_id

CROSS JOIN users u

WHERE u.user_id = 12345 -- The Current User

)

Step 4: The Fusion (Final Polish)

Finally, we combine the signals. We take a weighted average: 50% for the text match (relevance) and 50% for the user match (personalization).

SELECT

title,

(0.5 * normalized_bm25 + 0.5 * personal_score) as final_score

FROM personalized_ranking

ORDER BY final_score DESC

LIMIT 10;

This composable approach allows you to tune the knobs. Want personalization to matter more? Change the 0.5 weight. Want to filter candidates differently? Change the first_pass CTE. It’s just SQL.

Other Recommender Engine Workloads

There are few more workloads that can be supported in a similar way inside Postgres.

- Collaborative filtering (Users Like Me): Find other users who are similar to a user id. This can be directly used or used as a subquery to find items liked by similar users.

- Real-time Updates via Triggers: Whenever a user’s behavior changes or a new rating arrives, a trigger can update the user’s embedding in real time.

Trade-offs: The Landscape

No architecture is perfect. While the "In-Database" approach offers unbeatable simplicity, it helps to understand where it sits in the broader landscape of personalization strategies.

1. In Application Layer Inference (Python/Node.js)

Fetch data and re-rank it in your application code or a dedicated microservice.

- Pro: Maximum Flexibility. Use arbitrary logic and complex ML models (PyTorch/TensorFlow) that might be hard to express in SQL.

- Con: The "Data Transfer Tax". You ship thousands of candidate rows over the network just to discard most of them, adding latency and serialization overhead.

2. Dedicated Inference Platforms (e.g. Ray Serve, NVIDIA Triton)

Perform retrieval in a database, then send candidate IDs to a dedicated inference cluster for GPU-accelerated reranking.

- Pro: State-of-the-Art Accuracy. Run massive deep learning models too heavy for a standard database.

- Con: Infrastructure Sprawl. You’re managing a database and an ML cluster, plus paying latency for every network hop.

3. The "Cross-Encoder" Approach (e.g. Cohere Re-ranker)

Instead of comparing pre-computed embeddings (a Bi-Encoder), a Cross-Encoder feeds both query and document into the model simultaneously.

- Pro: Maximum Accuracy. Cross-encoders understand word interactions between query and document.

- Con: The Latency & Cost Cliff. You must run this heavy model at query time for every candidate — typically 200-500ms extra latency, plus third-party API costs and privacy concerns.

The ParadeDB Sweet Spot

The landscape above shows a spectrum: application-layer reranking offers flexibility but adds latency; dedicated inference platforms offer accuracy but add infrastructure; cross-encoders offer precision but add cost and privacy concerns.

The in-database approach hits a sweet spot for 95% of use cases. You get hybrid search and personalization with zero added infrastructure. No inference clusters, no reranker API calls, no ETL pipelines. Just Postgres. For the 5% of cases where squeezing out the final drops of relevance is worth the extra latency and vendor cost, a cross-encoder may be the right choice.

The main consideration? Resource Management. Because search runs on your database, it shares CPU and RAM with your transactional workload. For most applications, this is a non-issue given Postgres’s efficiency. For high-scale deployments, you can run search on a dedicated read replica to isolate inference load from your primary writes. ParadeDB supports two approaches:

- Physical replication: The BM25 index exists on the primary. Small write cost, but read queries can be routed to specific full replicas.

- Logical replication: The BM25 index is isolated to a replica subset only. No transactionality guarantees, but proper workload isolation.

The best approach depends on your infrastructure and requirements.

Conclusion

By pushing this logic into the database, we achieve Simplicity.

There is no "synchronization lag" where a user rates a movie but their recommendations don’t update for an hour. There is no fragile ETL pipeline to debug when recommendations look weird. There is no network latency adding 50ms to every search request while data travels to a ranker.

This pattern isn’t just a PostgreSQL trick; it’s a fundamental optimization principle called Compute Pushdown. You see it everywhere in high-performance computing:

- Big Data: Modern data warehouses like BigQuery and Snowflake push filtering logic down to the storage layer to avoid scanning petabytes of data.

- Edge Computing: IoT devices process sensor data locally (at the "edge") rather than sending every raw byte to the cloud, saving massive bandwidth.

ParadeDB applies this same principle to search: Move the compute to the data, not the data to the compute. Treat personalization as a database query rather than an application workflow. You simplify the stack, reduce latency, and get a unified engine for both search and recommendations.

Have a recommender workload you’d like to see in Postgres? Write to us in the ParadeDB Slack community.