Published on January 28, 2026 7:17 AM GMT

There is something it feels like to make a choice. As I decide how to open this essay, I have the familiar sense that I could express these ideas in many ways. I weigh different options, imagine how each might land, and select one. This process of deliberation is what most people call “free will”, and it feels undeniably real.

Yet some argue it’s an illusion. One prominent opponent of the concept of free will is the author, podcaster, and philosopher Sam Harris. He has written a book on free will, spoken about it in countless public <a href…

Published on January 28, 2026 7:17 AM GMT

There is something it feels like to make a choice. As I decide how to open this essay, I have the familiar sense that I could express these ideas in many ways. I weigh different options, imagine how each might land, and select one. This process of deliberation is what most people call “free will”, and it feels undeniably real.

Yet some argue it’s an illusion. One prominent opponent of the concept of free will is the author, podcaster, and philosopher Sam Harris. He has written a book on free will, spoken about it in countless public appearances, and devoted many podcast episodes to it. He has also engaged with defenders of free will, such as a lengthy back-and-forth and podcast interview with the philosopher Dan Dennett.

This essay is my attempt to convince Sam[1]of free will in the compatibilist sense, the view that free will and determinism are compatible. Compatibilists like me hold that we can live in a deterministic universe, fully governed by the laws of physics, and still have a meaningful notion of free will.

In what follows, I’ll argue that this kind of free will is real: that deliberation is part of the causal pathway that produces action, not a post-hoc story we tell ourselves. Consciousness isn’t merely witnessing decisions made elsewhere, but is instead an active participant in the process. And while none of us chose the raw materials we started with, we can still become genuine agents: selves that reflect on their own values, reshape them over time, and act from reasons they endorse. My aim is to explore where Sam and I disagree and to offer an account of free will that is both scientifically grounded and faithful to what people ordinarily mean by the term.

A Pledge Before We Start

Before we get too deep, I want to take a pledge that I think everyone debating free will should take:

I acknowledge that I am entering a discussion of “free will” and I solemnly swear to do my best to ensure we do not talk past each other. In pursuit of that, I will not implicitly change the definition of “free will”. If I dispute a definition, I will own it and explicitly say, “I hereby dispute the definition”.

I say this, in part, to acknowledge that some of the difference is down to semantics, but also that there’s much more than that to explore. I’ll aim to be clear about when we are and are not arguing over definitions. In defining “free will”, I’ll start with the intuitive sense in which most people use the term and I’ll sharpen it later.

While we’re on definitions, we should also distinguish between two senses of “could”. Here are the two definitions:

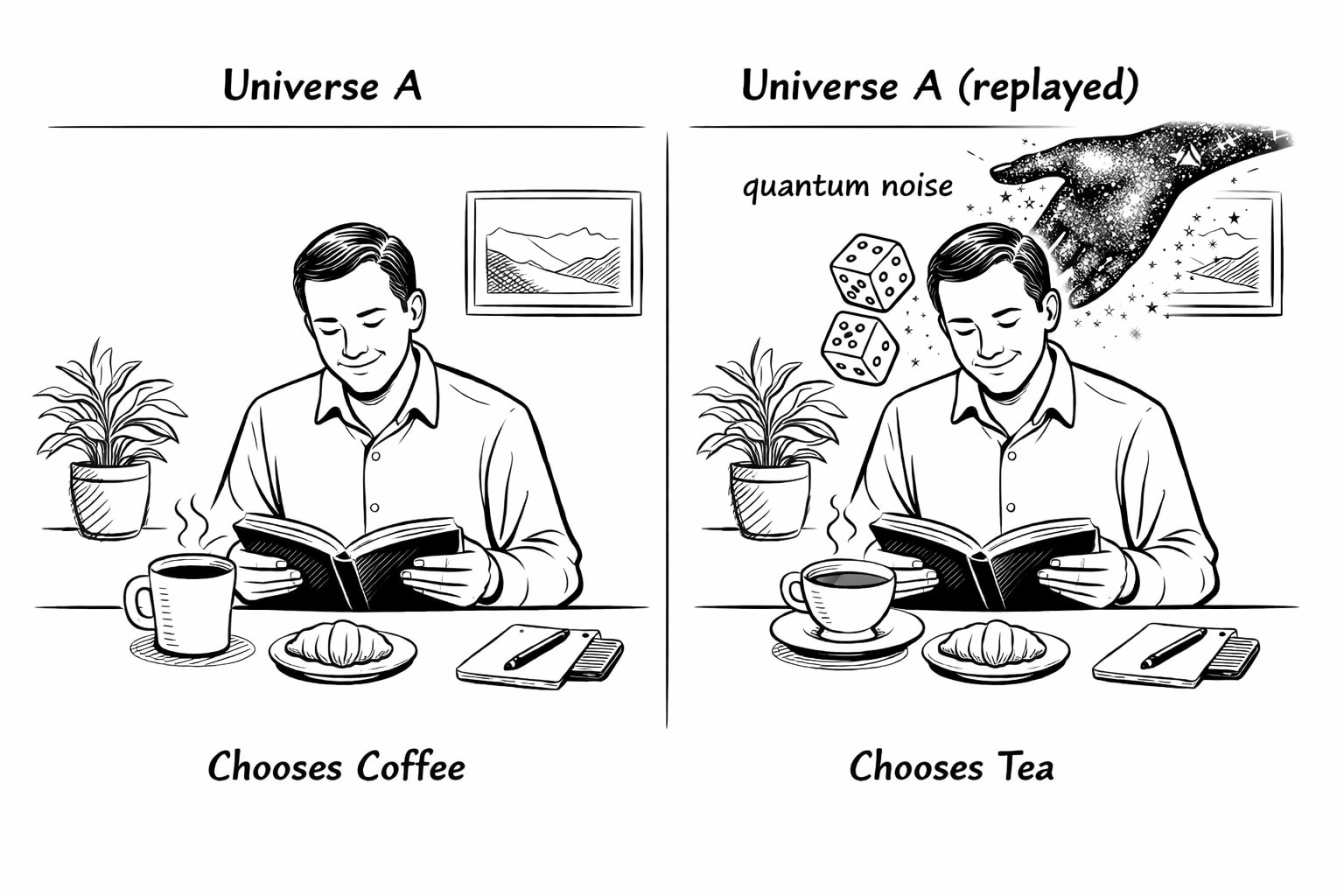

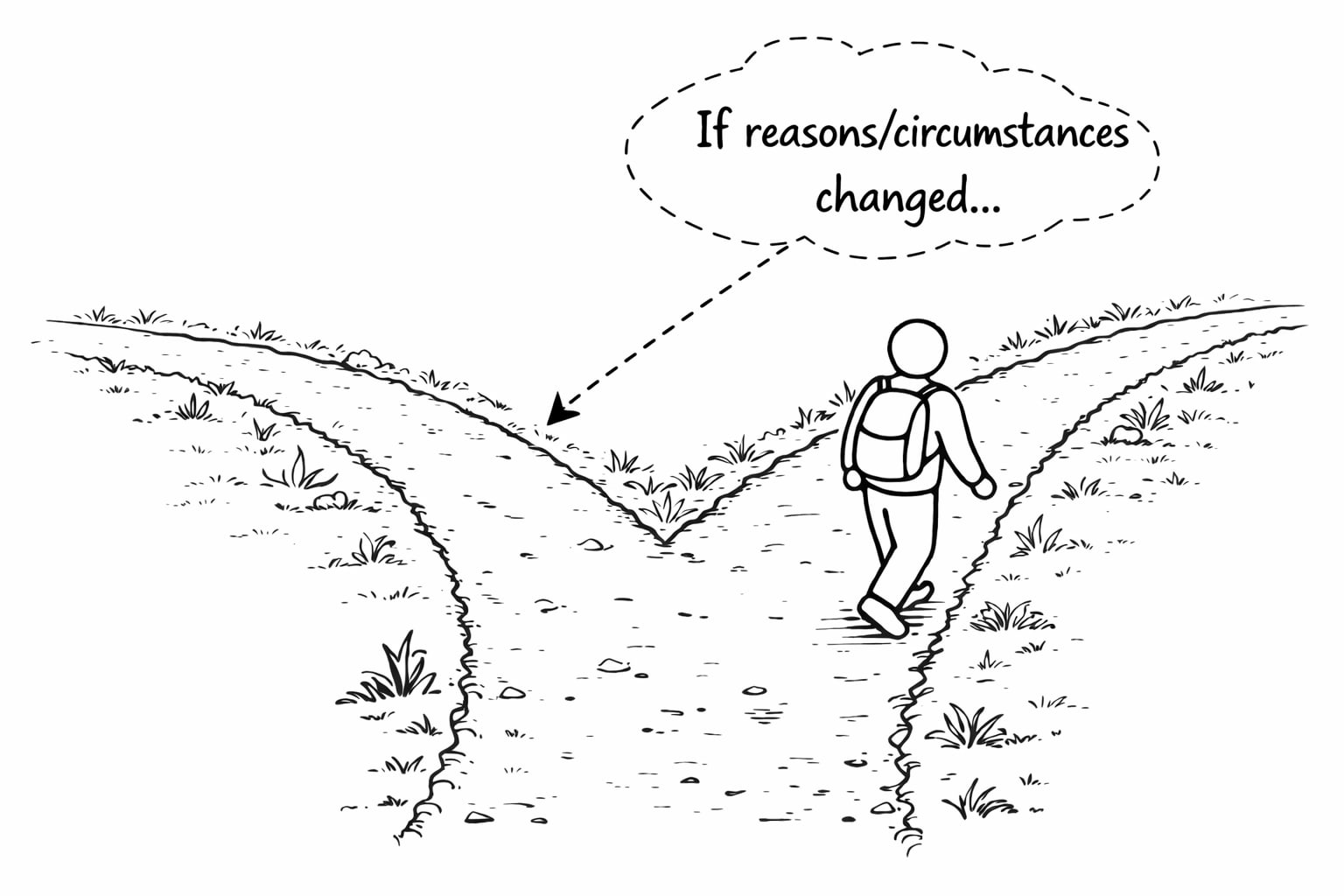

- We’ll use Could₁ to mean “could have done otherwise if my reasons or circumstances were different”.

- We’ll use Could₂ to mean “could have done otherwise even if we rewound the universe to the exact same state—same atoms, same brain state, same everything—and replayed it”.

Here’s an example of each case:

- Sam often uses the example of choosing between coffee and tea. Let’s say you chose coffee this morning. If your doctor had told you that you need to cut out coffee, you could have chosen tea instead. That’s Could₁. If we rewound the universe back to how it was when you made your decision and replayed the tape, you could not have chosen otherwise, no matter how many times you tried. That would be Could₂. So in this case, you Could₁ but not Could₂ have chosen tea.

- Imagine instead that your choices are at least partially determined by quantum noise, and that this is a fundamentally random process. If you rewound the universe and replayed it, you really might have made a different choice. That’s Could₂. But notice: if quantum noise determined your choice yet no amount of reasoning could have changed it, you’d have Could₂ without Could₁—you could have done otherwise, but only by luck, not by thinking. That would be a strange notion of freedom.

Compatibilist “free will”, which is what I’m arguing for, is about Could₁, not Could₂.

Sam’s Position

Areas of Agreement

Let me start with a list of things Sam and I agree on. I know not everyone will agree on these points, but Sam and I do, so, fair warning, some of these I’m not going to discuss in detail. I’ve used direct quotes from Sam when possible. In other cases I’ve used my wording but I believe Sam would agree with it:

- Determinism: “Human thought and behavior are determined by prior states of the universe and its laws.” Humans and consciousness are fully governed by the laws of physics.

- No libertarian free will: Neither of us believes in libertarian[2]free will, which is the idea that a person could (Could₂) have acted differently with all physical facts held constant.

- Randomness doesn’t help: The presence of randomness doesn’t create free will. If there is also some fundamental randomness in the universe (e.g. from quantum physics), that doesn’t rescue free will because you didn’t choose which random path to go down. That might give you Could₂, but it doesn’t give you Could₁, which, I believe, is what matters for free will.

- Souls don’t help: Even if people have souls, this probably doesn’t change anything because you likely didn’t choose your own soul.[3]

- Determinism does not mean or imply fatalism: We are both determinists, but not fatalists. It does not follow from “everything is determined” to “nothing you do matters”.

- No ultimate authorship: Ultimately, you did not choose to be you. You did not choose your genes, parents, childhood environment, and so on.

- Accountability should be forward-looking: “Holding people responsible for their past actions makes no sense apart from the effects that doing so will have on them and the rest of society in the future (e.g. deterrence, rehabilitation, keeping dangerous people off our streets).”

- Incarceration and contract enforcement still make sense: Nothing Sam or I believe suggests that, as Dan Dennett says about Sam’s position, “not only should the prisons be emptied, but no contract is valid, mortgages should be abolished, and we can never hold anybody to account for anything they do.”

- We must decouple two distinct questions of free will: The metaphysical question (does free will exist?) is separate from the sociological question (what happens if people believe it does or doesn’t?). Some argue for free will by saying belief in it leads to good outcomes (personal responsibility, motivation), or that disbelief leads to nihilism or fatalism. Sam and I agree these arguments are irrelevant to whether free will actually exists. The truth of a claim is independent of the consequences of believing it.

Sam’s Thought Experiment

Sam argues that we do not have free will.[4]In the podcast, “Final Thoughts on Free Will” (transcript here), he provides an excellent thought experiment explaining his position. I quote sections of it below, but if you’re interested, I recommend listening to it in his voice. (I find it quite soothing.) Click here to jump right to the thought experiment and listen for the next nine and a half minutes. But in case you don’t want to do that, here’s what he says (truncated for brevity):

Think of a movie. It can be one you’ve seen or just one you know the name of; it doesn’t have to be good, it can be bad; whatever comes to mind, doesn’t matter. Pay attention to what this experience is like.

A few films have probably come to mind. Just pick one, and pay attention to what the experience of choosing is like. Now, the first thing to notice is that this is as free a choice as you are ever going to make in your life. You are completely free. You have all the films in the world to choose from, and you can pick any one you want.

[…]

What is it like to choose? What is it like to make this completely free choice?

[…]

Did you see any evidence for free will here? Because if it’s not here, it’s not anywhere. So we better be able to find it here. So, let’s look for it.

[…]

There are many other films whose names are well known to you—many of which you’ve seen but which didn’t occur to you to pick. For instance, you absolutely know that The Wizard of Oz is a film, but you just didn’t think of it.

[…]

Consider the few films that came to mind—in light of all the films that might have come to mind but didn’t—and ask yourself, ‘Were you free to choose that which did not occur to you to choose?’ As a matter of neurophysiology, your The Wizard of Oz circuits were not in play a few moments ago for reasons that you can’t possibly know and could not control. Based on the state of your brain, The Wizard of Oz was not an option even though you absolutely know about this film. If we could return your brain to the state it was in a moment ago and account for all the noise in the system—adding back any contributions of randomness, whatever they were—you would fail to think of The Wizard of Oz again, and again, and again until the end of time. Where is the freedom in that?

[…]

The thing to notice is that you as the conscious witness of your inner life are not making decisions. All you can do is witness decisions once they’re made.

[…]

I say, ‘Pick a film’, and there’s this moment before anything has changed for you. And, then the names of films begin percolating at the margins of consciousness, and you have no control over which appear. None. Really, none. Can you feel that? You can’t pick them before they pick themselves.

[…]

If you pay attention to how your thoughts arise and how decisions actually get made, you’ll see that there’s no evidence for free will.

Free Will As a Deliberative Algorithm

I wanted to see if I could write down my process of making a decision to see if I could “find the free will” in it. I wrote down the following algorithm. Note that it is not in any way The General Algorithm for Free WillTM, but merely the process I noticed myself following for this specific task. Here’s what it felt like to me:[5]

- Set a goal

- In this case, the goal is just “name a movie”.

- Decide on a course of actions to reach the goal

- I realize I’ll need to remember some movies and select one. The selection criteria don’t matter that much.

- Generate options

- To generate options, I simply instruct my memory to recall movies. I can also add extra instructions in my internal dialog to see if that triggers anything: “What about Halloween movies, aren’t there more of those? Oh, yeah, that reminds me, what about more Winona Ryder movies? I must know some more of those.”

- Receive response

- The names of movies just pop into my head. More precisely, I should say they “become available to my consciousness” or “my consciousness becomes aware of them”.

- Simulate and evaluate each option

- I hold candidates in working memory and simulate saying them. I reason about each option (will this achieve my goal? What are the pros/cons?) Then I evaluate each option and each returns a response like “yes, I can say this” / “no, this doesn’t achieve the goal” (maybe it’s a book and not actually a movie). It also returns some sense of how much I “like” the answer based on my utility function[6]. This is the thing that makes “Edward Scissorhands” feel like a better answer than “Transformers 4,” even though both are valid movies. Maybe I want to seem interesting, or I genuinely loved that film, or I have a thing for Winona Ryder. Whatever the reason, I get an additional response of “yes, that’s a good answer” or “eh, I can do better.”

- Commit to a decision[7]

- I can reflect further on my choice. I hear Regis’ voice asking, “Is that your final answer?” Eventually, I tell myself that I am satisfied with my answer, and commit to it.

- Say my answer

- I say it out loud (if I’m with others) or just say it to myself. Either way, I feel like I have made the decision.

- Reflect on my choice

- I reflect on my decision. I feel ownership of my actions. I feel proud or embarrassed by my answer (“Did I really say that movie? In front of these people? Was that the best I could do?”).

So, where does this algorithm leave me? It leaves me with a vivid sense that “I chose X, but I could have chosen Y”. I can recall simulating the possibilities, and feel like I could have selected any of them (assuming they were all valid movies). In this case, when I say “could”, I’m using Could₁: I could (Could₁) have selected differently, had my reasons or preferences been different. It’s this sense of having the ability to act otherwise that makes me feel like I have free will, and it falls directly out of this algorithm.

This was simply the algorithm for selecting a movie, but this general structure can be expanded for more complex situations. The goal doesn’t have to be a response or some immediate need, but can include higher-order goals like maintaining a diet, self-improvement, or keeping promises. The evaluation phase would be significantly more elaborate for more complex tasks, such as thinking about constraints, effects on other people, whether there’s missing information, and so on. Even committing to a decision might require more steps. I might ask myself, “Was this just an impulse? Do I really want to do this?” And, importantly, I can evaluate the algorithm itself: “Do I need to change a step, or add a new step somewhere?”

In short, I’m saying free will is this control process, implemented in a physical brain, that integrates goals, reasons, desires, and so on. Some steps are conscious, some aren’t. What matters is that the system is actively working through reasons for action, not passively witnessing a foregone conclusion. (Perhaps there is already a difference in definition from Sam’s, but I want to put that aside for another moment to fully explain how I think about it, then we’ll get to semantics.)

So when someone asks, “Did you have free will in situation X?” translate it to: “Did your algorithm run?”

Constraints and Influences

Let me be clear about what I’m not claiming. My compatibilist free will doesn’t require:

Freedom from constraint. Sam points out that saying “Wizard of Oz” was not an option if I didn’t think of it at the time, even if I know about the film. This is true. But free will doesn’t mean you can select any movie, or any movie you’ve seen, or even any movie you’ve seen that you could remember if you thought longer. It just means that the algorithm ran. You had the free will to decide how much thought to put into this task, you had the free will to decide you had thought of enough options, and you had the free will to select one.

Consider a more extreme case: someone puts a gun to your head and demands your wallet. Do you have any free will in this situation? Your options are severely constrained—you could fight back, but I wouldn’t recommend it. However, you can still run the algorithm, so you have some diminished, yet non-zero amount of free will in this case. For legal and moral reasons, it would likely not be enough to be considered responsible for your actions (depending on the specific details, as this is a question of degree).

In these scenarios, you have constrained choices. Constraints come in many forms: physical laws (you can’t choose to fly), your subconscious (Wizard of Oz just didn’t come to mind), other people (the gunman), time, resources, and so on. None of these eliminates free will, because free will isn’t about having unlimited options; it’s about running the deliberative algorithm with whatever options you do have.

Freedom from influence. Sam gives many examples of how our decisions are shaped by things we’re unaware of, such as priming effects, childhood memories, and neurotransmitter levels. That’s fine. Free will is running the algorithm, not being immune to influence. Your algorithm incorporates these influences. It isn’t supposed to ignore them.

Perfect introspection. You don’t need complete understanding as to why certain movies popped into your head or why you weighed one option over another.

We have some level of introspection into what goes on inside our brains, though it’s certainly not perfect, or maybe even very good. We confabulate more than we’d like to admit and spend a lot of time rationalizing after the fact. But the question isn’t whether you can accurately report your reasoning; it’s whether reasoning occurred. The algorithm works even when you can’t fully explain your own preferences.

Complete unpredictability. Free will doesn’t require unpredictability. If I offer you a choice between chocolate ice cream and a poke in the eye with a sharp stick, you’ll pick the ice cream every time. That predictability doesn’t mean you lack free will; it just means the algorithm reached an obvious conclusion. The question isn’t about whether the results were predictable, but whether the deliberative control process served as a guide versus being bypassed.

I think these distinctions resolve many of the issues Sam brings up. To hear them, you can listen to the thought experiment 42 minutes into the podcast episode Making Sense of Free Will. If you have these clarifications in mind, you’ll find that his objections don’t threaten compatibilist free will after all. See “Responding to Another Sam Harris Thought Experiment” in the appendix for my walkthrough of that thought experiment.

Objections, Your Honor

Let’s address some likely objections to this algorithmic account of free will.

Exhibit A: Who Is This “I” Guy?

Much of this might sound circular—who is the “I” running the algorithm? The answer is that there’s no separate “I”. When I say “I instruct my memory to recall movies,” I mean that one part of my neural circuitry (the part involved in conscious intention) triggers another part (the part responsible for memory retrieval). There’s no homunculus, no little person inside doing the real deciding. The algorithm is me.

This is why I resist Sam’s framing. Sam says my Wizard of Oz circuits weren’t active “for reasons I can’t possibly know and could not control.” But those reasons are neurological—they’re part of me. When he says “your brain does something,” he treats this as evidence that you didn’t do it, as if you were separate from your brain, watching helplessly from the sidelines. But my brain doing it is me doing it. The deliberative algorithm running in my neurons is my free will. Or, to quote Eliezer Yudkowsky, thou art physics.

The algorithm involves both conscious and subconscious processes. Some steps happen outside awareness—like which movies pop into my head. But consciousness isn’t merely observing the process; it’s participating in it: setting goals, deciding on a course of action, evaluating options, vetoing bad ideas. I’m not positing a ghost in the machine. I’m saying the machine includes a component that does what we call “deliberation,” and that component is part of the integrated system that is me.

Exhibit B: So, it’s an illusion?

Someone might say, “Ok, you’ve shown how the feeling of free will falls out of a deterministic process. So you’ve shown it’s an illusion, right?”

No! The deliberative algorithm is not just a post-hoc narrative layered on top of decisions made elsewhere; it is the causal process that produces the decision. The subjective feeling of choosing corresponds to the real computational work that the system performs.

If conscious deliberation were merely a spectator narration, then changing what I consciously attend to and consider would not change what I do. But it does. If you provide new reasons for my conscious deliberation—“don’t choose My Little Pony or we’ll all laugh at you”—I might come up with a different result.[8]

It’s certainly possible to fool oneself into thinking you had more control than you actually did. I’ve already admitted that I don’t have full introspective access to why my mind does exactly what it does. But if this is an illusion, it would require that something other than the deliberative algorithm determines the choice, while consciousness merely rationalizes afterward. This is not so; the algorithm is the cause. Conscious evaluation, memory retrieval, and reasoning are not epiphenomenal but instead are the steps by which the decision is made.

Exhibit C: Did you choose your preferences?

Did I choose my preferences? Mostly no, but they are still my preferences. I’ll explore this more later, but, for now, I’m happy to concede that I mostly didn’t choose my taste in music, books, movies, or anything else. They were shaped by my genes, hormones, experiences, and countless other factors, none of which I selected from some prior vantage point. Puberty rewired my preferences without asking permission.

But this doesn’t threaten free will as I’ve defined it (we’ll get to semantics later, I promise). The algorithm takes preferences as inputs and works with them. It doesn’t require that you author those inputs from scratch.

The objection against identifying with my own preferences amounts to saying, “You didn’t choose to be you, therefore you have no free will.” But this sets an impossible standard. To choose your own preferences, you’d need some prior set of preferences to guide the selection, and then you’d need to have chosen those, and so on, forever. The demand is incoherent. What remains is the thing people actually care about: that your choices flow from your values, through your reasoning, to your actions. That’s free will. You can’t choose to be someone else, but you can choose what to do as the person you are.

Exhibit D: What about those Libet Experiments?

What about those neuroscience experiments that seem to show decisions being made before conscious awareness? Don’t these prove consciousness is just a passive witness?

The classic evidence here comes from Libet-style experiments (meta-analysis here), where brain activity (the “readiness potential”) appears before participants report awareness of their intention to move.[9]These findings are interesting, but they don’t show that the entire deliberative algorithm I’ve described is epiphenomenal. When researchers detect early neural activity preceding simple motor decisions, they’re detecting initial neural commitments in a task with no real stakes and no reasoning required. This doesn’t bypass conscious evaluation, simply because there’s barely any evaluation to bypass.

In Sam’s movie example, the early “popping into consciousness” happens subconsciously, and I grant that. But the conscious evaluation, simulation, and selection that follows is still doing real computational work. The Libet experiments show consciousness isn’t the first step, but they don’t show it’s causally inert. To establish that, we would need to see complex decisions where people weigh evidence, consider consequences, and change their minds, being fully determined before any conscious evaluation occurs.[10]

There are also more dramatic demonstrations, like experiments where transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) activates the motor cortex opposite to the one a participant intended to use, forcing the “wrong” hand to move. When asked why they moved that hand, participants say things like “I just changed my mind.” I’ve actually talked about these studies before. I agree that they show that consciousness can invent explanations for actions it didn’t cause. But confabulation in artificial, forced-movement scenarios doesn’t prove that deliberation is always post-hoc rationalization. It proves we can be fooled when experimenters hijack the system.

Exhibit E: Aren’t You Just the Conscious Witness of Your Thoughts?

Sam has repeatedly referred to our conscious experience as a mere witness to our actions. In his book, he said (my bolding):

I generally start each day with a cup of coffee or tea—sometimes two. This morning, it was coffee (two). Why not tea? I am in no position to know. I wanted coffee more than I wanted tea today, and I was free to have what I wanted. Did I consciously choose coffee over tea? No. The choice was made for me by events in my brain that I, as the conscious witness of my thoughts and actions, could not inspect or influence. Could I have “changed my mind” and switched to tea before the coffee drinker in me could get his bearings? Yes, but this impulse would also have been the product of unconscious causes. Why didn’t it arise this morning? Why might it arise in the future? I cannot know. The intention to do one thing and not another does not originate in consciousness—rather, it appears in consciousness, as does any thought or impulse that might oppose it.

[…]

I, as the conscious witness of my experience, no more initiate events in my prefrontal cortex than I cause my heart to beat.

He’s made similar arguments in his podcasts, such as Final Thoughts on Free Will (jump to 1:16:06 and listen for 1.5 minutes). In that episode, he responds to compatibilist philosophy by arguing that what “you” experience as conscious control is just being a conscious witness riding on top of unconscious neural causes, and calling all of that “you” (as compatibilists do) is a “bait-and-switch”. That is, compatibilists start with “you” in the intuitive sense—the conscious self—but then expand it to include all the unconscious processes you never experience or control. By that sleight of hand, Sam argues, compatibilists can say “you” chose freely, but only because they’ve redefined “you” to mean something the ordinary person wouldn’t recognize. He concludes by saying, “The you that you take yourself to be isn’t in control of anything.”

I think this is a key crux of our disagreement. Sam sees consciousness as a mostly passive observer[11]. I think it’s an active participant, a working component of the deliberative algorithm. Contrary to his claim, I think it can initiate events in your prefrontal cortex AND influence your heartbeat.

Here’s a simple demonstration: tell yourself to think about elephants for the next five seconds. Your conscious intention just shaped what happened in your prefrontal cortex. You don’t have complete control—it wouldn’t surprise me if a to-do list or a “did I turn off the stove?” trampled upon your elephantine pondering, but your conscious direction influenced events in your prefrontal cortex.

Of course, Sam would protest that the conscious intention to think about elephants arose from unconscious causes. This is true. But we need to distinguish origination (which I concede is unconscious) from governance. Even if the thought arose from the unconscious, it still went into the algorithm before you decided to act upon it. Therefore, you still had the ability to consciously deliberate, revise it if needed, or simply veto the whole idea.

I think Sam’s analogy to heartbeats actually backfires. He means to show that consciousness is as powerless over thought as it is over cardiac rhythm. But notice that you can influence your heartbeat: imagine a frightening scenario vividly enough and your heart rate will increase. You can’t stop your heart by willing it, but you can modulate it within a meaningful range.

I think this is a miniaturized version of a larger disagreement. Sam looks to the extremes and says, “You can’t choose what thoughts appear in your mind. You can’t stop your heart. You can’t inspect the rationale for your thoughts and actions. Looks bad for free will.” I look at the proximate areas and say, “You can choose to light up your elephant neural circuitry. You can choose to increase your heart rate. You can inspect the rationale for your thoughts and actions, albeit imperfectly. There’s plenty of free will here.” Your consciousness isn’t omnipotent, but it isn’t impotent either. It can modulate physiology, focus attention, and do real causal work while operating within constraints.

Sam is generally unimpressed with these sorts of claims. In his book, he quips: “Compatibilism amounts to nothing more than an assertion of the following creed: A puppet is free as long as he loves his strings.” But this gets the distinction backwards. A puppet would be unfree if the strings were pulled by an external controller, bypassing its algorithm. A person is free (in the compatibilist sense) when the “strings” are their own values, reasoning, and planning, and when the algorithm isn’t being bypassed but is the thing doing the pulling.

I understand where Sam is coming from. I’ve said before that sometimes our executive function seems more like the brain’s press secretary. But notice what a press secretary actually does. A pure figurehead would be someone who learns about decisions only after they’re final. A real press secretary sits in on the meetings, shapes messaging strategy, and sometimes pushes back on policy because of how it will play. The question isn’t whether consciousness has complete control, but whether it’s contributing in the room when decisions get made.

Confabulation research shows that we sometimes invent explanations after the fact. It doesn’t show that we always do, or that conscious reasoning never contributes. Again, the test is the counterfactual. You gave me a reason not to choose My Little Pony mid-deliberation, and it changed my decision. This means the conscious reasoning is doing real causal work, not just narration. That’s compatible with also sometimes confabulating. We’re imperfect reasoners, not mere witnesses.

Pathological Cases

Maybe a way to make the distinction between merely witnessing and being an active participant more clear is to talk about pathological cases. There are conditions where consciousness really does seem to be a mere witness, and, notably, we recognize them as pathologies:

- Alien hand syndrome—Here’s how the Cleveland Clinic describes alien hand syndrome: “Alien hand syndrome occurs when your hand or limb (arm) acts independently from other parts of your body. It can feel like your hand has a mind of its own. […] With this condition, you aren’t in control of what your hand does. Your hand doesn’t respond to your direction and performs involuntary actions or movements.”

Here’s an example from the Wikipedia page: “For example, one patient was observed putting a cigarette into her mouth with her intact, ‘controlled’ hand (her right, dominant hand), following which her left hand rose, grasped the cigarette, pulled it out of her mouth, and tossed it away before it could be lit by the right hand. The patient then surmised that ‘I guess “he” doesn’t want me to smoke that cigarette.’” - Epileptic automatisms—Neuropsychologist Peter Fenwick defined it as follows: “An automatism is an involuntary piece of behaviour over which an individual has no control. The behaviour is usually inappropriate to the circumstances, and may be out of character for the individual. It can be complex, co-ordinated and apparently purposeful and directed, though lacking in judgment. Afterwards the individual may have no recollection or only a partial and confused memory for his actions.”

- Tourette syndrome—The paper Tourette Syndrome and Consciousness of Action says this: “Although the wish to move is perceived by the patient as involuntary, the decision to release the tic is often perceived by the patient as a voluntary capitulation to the subjective urge.”

- Schizophrenia—Here’s how one person with schizophrenia described an experience: “It is my hand and arm that move, and my fingers pick up the pen, but I don’t control them. What they do is nothing to do with me.”

How does any of this make sense if the non-pathological “you” is only a witness to actions? There would be no alien hand syndrome as it would all be alien. There could be no distinction between voluntary and involuntary behavior if it’s all involuntary to our consciousness. To me, these are all cases where consciousness isn’t able to play the active, deliberate role that it usually plays. What are these in Sam’s view?

Proximate vs Ultimate Authorship

A key distinction has been lurking in the background of this discussion, and it’s time to make it explicit: the difference between proximate and ultimate authorship of our actions.

Proximate authorship means your deliberative algorithm was the immediate cause of an action. The decision ran through your conscious evaluation process: you weighed your options, considered the consequences, selected a course of action, and, afterwards, felt like you could (Could₁) have selected otherwise. In this sense, you authored the choice.

Ultimate authorship would mean you are the ultimate cause of your actions. This would mean that, somehow, the causal chain traces back to you and stops there.

Sam and I agree that no one has ultimate authorship. The causal chain does not stop with you. You did not choose to be you. Your deliberative algorithm—the very thing I’m calling “free will”—was itself shaped mostly by factors outside your control:

- Your genes, which you didn’t select

- Your childhood environment, which you didn’t choose

- Your experiences, which are mostly a combination of events outside your control and the above, which you didn’t choose

This could go on and on. The causal chain stretches back through your parents, their parents, the evolution of the human brain, the formation of Earth, up to the Big Bang. As Carl Sagan put it, “to make an apple pie you must first invent the universe.” I have invented no universes; therefore, I have ultimate authorship over no apple pies (though I do have proximate authorship over many delicious ones, just for the record).

How to Make an Agent out of Clay

So how are we, without ultimate authorship, supposed to actually be anything? When does it make sense to think of ourselves as agents, with preferences we endorse, reasons we respond to, and a will of our own? In short, how do we become a “self”?

Earlier I said my preferences were my preferences in some meaningful way, but how can that be if I didn’t choose them? And even if I did choose them, I didn’t choose the process by which I chose them. And if, somehow, I chose that as well, we can just follow the chain back far enough and we’ll reach something unauthored. That regress is exactly why ultimate authorship is impossible, and I’ve already conceded it.

But notice what the regress argument assumes: it gives all the credit to ultimate authorship and none to proximate authorship. By that standard, nothing we ordinarily call control or choice would count.

Consider a company as an example. Let’s say I make a bunch of decisions for my company. I say we’re going to build Product A and not Product B, we’re going to market it this way and not that way, and so on. In any common usage of the words, I clearly made those decisions—they were under my control. But did I, by Sam’s ultimate authorship standard? Well, the reason I wanted to build Product A is because I thought it would sell well. And that would generate revenue. And that would make the company more valuable. But, did I make the decision to set the goal of the company to be making money? Well, I wasn’t a founder of the company, so it wasn’t my idea to make a for-profit company in the first place. Therefore, by the standard of ultimate authorship, I had no control and made no decisions! The founders made every one of them when they decided to found a for-profit company. This, of course, is not how we think about decision-making and control.

What matters for agency isn’t whether your starting point was self-created; it’s whether the system can govern itself from the inside, whether it can reflect on its results and revise its own motivations over time.

Humans can evaluate their own evaluations. I can have competing desires and reason through them. I can want a cigarette but also not want to want cigarettes, and that second-order stance can reshape the first over time. That’s the feedback loop inside the decision-making system. The algorithm doesn’t just output actions; it can also adjust the weights it uses to produce future actions.

Here’s a real example from my life: I believe I’ve successfully convinced myself that I like broccoli. Years ago, I made a conscious decision to tell myself I really liked broccoli. I didn’t hate it prior, but I wouldn’t have said I particularly enjoyed it. But I decided I’d be better off if I did, so I gathered all my anti-rationalist powers and told myself I enjoyed the taste. I ate it more often, and each time I told myself how much I was enjoying it. Within a couple of years, I realized I wasn’t pushing anymore. I just liked broccoli. Frozen broccoli, microwaved with salt, pepper, and a little lemon juice, is now my go-to snack. And it’s delicious.

Now, we don’t have ultimate authorship of either the first-order desire (disliking broccoli) or second-order desire (wanting to have a healthier diet), so who cares? But notice what happened here. This wasn’t just a parameter being adjusted in some optimization process. It was me deciding what kind of person I wanted to be and reshaping my preferences to match. That’s me authoring at the proximate level and taking ownership of the kind of person I’m becoming. The broccoli preference became mine not because I authored it from scratch, but because I consciously endorsed and cultivated it. It coheres with who I take myself to be.

This matters because I want to show that, over time, humans can become coherent agents. I want to show that humans are a distinct category from just a pile of reflexes or a mere conscious witness to one’s actions.

And this is why the regress to ultimate authorship doesn’t touch what matters. If “ownership” required self-creation, then no belief, value, or intention would ever count as yours either, because those, too, trace back to unchosen influences. But that’s not how we actually draw the line. We treat a preference as yours when it is integrated into your identity.

Note what this reveals about entities that can have free will. To reflect on your own desires you have to be able to represent them as your desires. You have to be able to take yourself as an object of evaluation and revise yourself over time. That requires a self-model robust enough to support second‑order evaluation: not just “I want X,” but “do I want to be the kind of person who wants X?”

You can see how the sense of agency develops in humans over time. It wouldn’t make sense to describe an infant as much of an agent. But over time, humans develop a sense of who they are and who they want to be. They can reflect on themselves and change accordingly. The algorithm can, to some degree, rewrite its own code in light of an identity it is actively shaping. This is another sense in which proximate authorship is “enough”. Not only can we run the algorithm, we can modify it.

That capacity for self-editing is a real boundary in nature. It separates agents from mere processes. A muscle spasm can’t reflect on itself. A craving can’t decide it would rather be a different kind of craving. But I can, and that’s the distinction that matters when we ask whether someone acted freely.

Sam’s entire objection seems to boil down to the assumption that control requires ultimate authorship. But this assumption doesn’t hold.

Disputing Definitions

OK, some of this has gotten into semantics, so, in keeping with my pledge: I hereby dispute the definition.

As we’ve seen, when I say “I have free will,” I don’t mean I’m the ultimate, uncaused source of my decisions, untouched by genes, environment, or prior events. I mean I have the capacity to translate reasons, values, and goals into actions in a way that is responsive to evidence. Or, in short, to run the algorithm.

So why call this “free will”?

First, you can see how the feeling of free will falls out of this algorithm. When people say they “could have done otherwise,” they are feeling their choice-making algorithm at work, and, as I’ve shown, that algorithm really is at work. The phenomenon matches the feeling of free will, so I say it’s appropriate to call it that.

Second, I think this definition matches how people talk in everyday life. Consider the following:

- “I could have made that shot.”

- “You could have studied harder.”

- “The defendant could have acted differently.”

- “The car could have gone faster.”

- “It could have rained.”

In all of these, “could have” means something like, “given the situation, a different outcome was within reach under slightly different conditions.”

For example, consider “I could have made that shot.” If I miss a half-court shot, I might say “I could have made that shot.” By that, I mean that, given my skill, if I tried again under similar conditions, it’s possible I could have made it. Making it is within my ability. If I try a full-court shot and the ball falls 20 feet short, then I probably just couldn’t have made it. I lack the physical capacity.

This is Could₁. It’s about alternative outcomes across nearby scenarios (e.g. I could have made that shot if the wind was a little bit different).

Contrast that with what the sentence would mean if people were using Could₂. The sentence would be, “I could have made that shot even if everything about the past and the laws of nature were the same.” It says that, rewinding every atom in the universe and every law of physics, things could (Could₂) have gone differently. This is a completely different claim and it’s not what people mean when they use the word.