Introduction

OAuth 2 lets third-party apps access user data without handling passwords. Instead of asking users for their credentials, OAuth 2 delegates authentication to the service provider (like Google or GitHub) and issues tokens that represent specific permissions.

Here’s what you need to know: OAuth 2 is an authorization framework, not authentication. It answers “What can this app do?” not “Who is this user?” When you click “Sign in with Google” on a website, that’s typically OpenID Connect (which adds authentication) built on top of OAuth 2.

Why OAuth 2 exists: Before OAuth 2, applications either asked users for passwords (security risk) or required users to share API keys (too permissive). OAuth 2 solves this by letting us…

Introduction

OAuth 2 lets third-party apps access user data without handling passwords. Instead of asking users for their credentials, OAuth 2 delegates authentication to the service provider (like Google or GitHub) and issues tokens that represent specific permissions.

Here’s what you need to know: OAuth 2 is an authorization framework, not authentication. It answers “What can this app do?” not “Who is this user?” When you click “Sign in with Google” on a website, that’s typically OpenID Connect (which adds authentication) built on top of OAuth 2.

Why OAuth 2 exists: Before OAuth 2, applications either asked users for passwords (security risk) or required users to share API keys (too permissive). OAuth 2 solves this by letting users grant limited, revocable permissions. For example, a backup app can access your Google Drive files without your Google password, and you can revoke access anytime.

This guide shows you how OAuth 2 works, which grant types to use for different scenarios, and how to implement secure OAuth 2 flows in your applications.

Deploy your frontend applications from GitHub using DigitalOcean App Platform. Let DigitalOcean focus on scaling your app.

Key Takeaways

Before diving into the technical details, here are the essential points about OAuth 2:

- OAuth 2 provides authorization, not authentication. It allows applications to obtain permission to access resources but does not verify the user’s identity on its own.

- The OAuth 2 flow is defined by four core roles: Resource Owner, Client, Authorization Server, and Resource Server, each of which plays a part in enabling secure access.

- The Authorization Code grant is the standard approach for server-side applications where the client secret can be kept confidential.

- PKCE, or Proof Key for Code Exchange, is essential for public clients as it protects against authorization code interception attacks.

- Tokens issued by OAuth 2 have limited lifespans; access tokens expire, and refresh tokens allow applications to obtain new access tokens without user intervention.

- Scopes in OAuth 2 define the permissions being requested. Each authorization request specifies which resources and actions the application can access, such as read, write, or administrative privileges.

- OAuth 1 is now deprecated. OAuth 2 has replaced OAuth 1.0 due to improved security and a more straightforward implementation process.

From an application developer’s point of view, a service’s API fulfills both the resource and authorization server roles. We refer to both roles combined as the Service or API role.

What Is OAuth 2?

OAuth 2 is an authorization framework defined in RFC 6749 that enables third-party applications to obtain limited access to a user’s resources on an HTTP service. The framework standardizes how applications request and receive permission to access user data without exposing user credentials.

Think of OAuth 2 like a valet key for your car: you give a parking attendant a limited-use key that only opens the door and starts the engine, but doesn’t open the trunk or glove compartment. Similarly, OAuth 2 gives applications specific permissions (scopes) to access certain resources, without granting full account access.

OAuth 2 solves a critical security problem: applications no longer need to store user passwords. Instead, users authorize applications through the service provider (like Google or GitHub), which issues tokens that represent the granted permissions. This reduces the attack surface and gives users granular control over what each application can access.

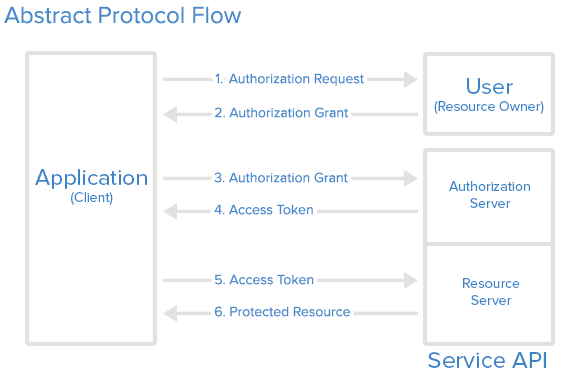

How OAuth 2 Works: The Basic Flow

OAuth 2 follows a six-step pattern regardless of which grant type you use. Understanding this flow helps you debug issues and choose the right grant type for your application.

Step 1: Application requests authorization. Your application redirects the user to the authorization server with a request for specific permissions (scopes).

Step 2: User authorizes the application. The user logs in (if needed) and approves or denies your application’s request. If approved, the authorization server generates an authorization grant.

Step 3: Application requests access token. Your application exchanges the authorization grant (plus your client credentials) for an access token. This happens server-to-server.

Step 4: Authorization server issues access token. If everything checks out, the server returns an access token (and optionally a refresh token) to your application.

Step 5: Application requests protected resource. Your application uses the access token to make API requests on behalf of the user.

Step 6: Resource server serves the resource. The API validates the token and returns the requested data if the token is valid and has the required scopes.

The specific grant type you choose determines how steps 1-4 work, but steps 5-6 are the same for all flows.

OAuth 2 vs Authentication vs OpenID Connect

Understanding the difference between OAuth 2, authentication, and OpenID Connect prevents common implementation mistakes.

OAuth 2 is authorization. It answers “What can this application do?” by granting permissions to access resources. OAuth 2 doesn’t verify who the user is; it assumes authentication already happened.

Authentication verifies identity. It answers “Who is this user?” by confirming credentials (username/password, biometrics, etc.). Authentication happens before OAuth 2 authorization begins.

OpenID Connect (OIDC) adds authentication to OAuth 2. Built on OAuth 2, OpenID Connect adds an ID token that contains user identity information. When you see “Sign in with Google,” that’s typically OpenID Connect using OAuth 2 underneath.

Here’s a comparison table:

| Aspect | OAuth 2 | Authentication | OpenID Connect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Authorization (permissions) | Identity verification | Both authentication and authorization |

| Answers | “What can this app do?” | “Who is this user?” | “Who is this user and what can they do?” |

| Token Type | Access token | Session token/cookie | ID token + access token |

| Use Case | API access, third-party integrations | Login systems | Social login, single sign-on |

| Example | App accessing your GitHub repos | Logging into your email | “Sign in with Google” button |

When to use each:

- Use OAuth 2 alone when you only need to grant API access (e.g., a backup tool accessing your cloud storage).

- Use authentication when building your own login system (e.g., username/password for your application).

- Use OpenID Connect when you need both identity and permissions (e.g., social login that also accesses user profile data).

Note: Many developers confuse OAuth 2 with authentication because popular implementations (like “Sign in with Google”) combine both. The OAuth 2 flow includes an authentication step (user logs in), but OAuth 2 itself only handles the authorization that follows.

OAuth 2 Roles Explained

OAuth 2 defines four roles that interact during the authorization process. Understanding these roles clarifies how OAuth 2 works in practice.

Resource Owner: The user who owns the resources (data, account, etc.) and can grant access to them. In real-world terms, this is you when you click “Allow” to let an app access your Google Drive files.

Client: The application requesting access to the user’s resources. This could be a mobile app, web application, or server-side service. The client must be registered with the authorization server before it can participate in OAuth 2 flows.

Authorization Server: The server that authenticates the resource owner and issues access tokens after successful authorization. This is typically the same service hosting the user’s account (e.g., Google’s authorization server for Google accounts).

Resource Server: The server hosting the protected resources (user data, APIs, etc.). It accepts and validates access tokens to determine if requests should be fulfilled. Often, the authorization server and resource server are the same service, but they can be separate for distributed architectures.

From an application developer’s perspective, the authorization server and resource server are often combined into a single “API” or “Service” that you’re integrating with. For example, DigitalOcean’s API handles both authorization (issuing tokens) and resource serving (providing droplet data).

Application Registration and Client Credentials

Before your application can use OAuth 2, you must register it with the service provider. Registration happens through the service’s developer portal or API management interface.

Application Registration Requirements

During registration, you’ll provide:

- Application Name: A human-readable name that users will see during authorization (e.g., “My Backup Tool”).

- Application Website: Your application’s homepage or documentation URL.

- Redirect URI (Callback URL): The exact URL where the authorization server will send users after they authorize or deny your application. This must match exactly what you specify in authorization requests.

Security Note: Register multiple redirect URIs if your application runs on different environments (development, staging, production). Never use wildcards or overly permissive redirect URIs, as attackers can exploit them to steal authorization codes.

Client ID and Client Secret

After registration, the service issues client credentials:

Client ID: A publicly exposed string that identifies your application. It’s safe to include in client-side code, URLs, and public repositories. The Client ID is used to build authorization URLs and identify which application is requesting access.

Client Secret: A confidential string that authenticates your application to the authorization server. Store it securely on your server (environment variables, secret managers) and only use it in server-to-server communication.

Security Critical: Never expose client secrets in:

- Frontend JavaScript code or mobile apps (use PKCE instead)

- Git repositories, even in .env files (use .gitignore)

- URLs or query parameters

- Client-side storage (localStorage, cookies)

- Error messages or logs

- Public documentation or screenshots

Compromised secrets require regeneration and redeployment of all clients.

OAuth 2 Authorization Grant Types

An authorization grant is a credential representing the resource owner’s authorization to access their protected resources. OAuth 2 defines several grant types, each optimized for different application architectures based on security requirements, client capabilities, and whether user interaction is possible.

Authorization Code: The most common grant type, designed for server-side applications where the client secret can be securely stored. This is a redirection-based flow that works through the user’s browser.

Client Credentials: Used for machine-to-machine communication where no user is involved. The application accesses its own resources or service account.

Device Code: Designed for input-constrained devices (smart TVs, IoT devices) that lack browsers or keyboards. Users authorize on a separate device.

Deprecated Grant Types: OAuth 2 originally included Implicit Flow and Resource Owner Password Credentials grant types. Both are now considered insecure and deprecated:

- Implicit Flow: Tokens were returned directly in the URL fragment, making them vulnerable to interception. Use Authorization Code with PKCE instead.

- Password Grant: Applications collected user passwords directly, violating OAuth 2’s core security principle. Never use this grant type.

The grant type you choose depends on your application architecture, security requirements, and the capabilities of your client application. We’ll explore each recommended grant type in detail below.

Authorization Code Flow (Step-by-Step)

The Authorization Code grant type is the standard for server-side web applications, mobile apps, and single-page applications. It’s secure because the access token is never exposed to the user-agent (browser); only the authorization code is transmitted, which is then exchanged server-side for the token.

When to Use Authorization Code Flow

Use this flow when:

- Your application has a server component that can securely store the client secret

- You’re building a web application, mobile app, or desktop application

- You need the highest level of security for user authorization

Step 1: Build the Authorization URL

The application redirects the user to an authorization URL that includes several parameters:

https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/authorize?response_type=code&client_id=CLIENT_ID&redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL&scope=read&state=RANDOM_STATE_STRING

URL Components Explained:

response_type=code: Tells the authorization server you’re requesting an authorization code grantclient_id=CLIENT_ID: Your registered application’s client IDredirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL: Must exactly match a redirect URI registered with your applicationscope=read: The permissions you’re requesting (common scopes:read,write,admin)state=RANDOM_STATE_STRING: A random value you generate to prevent CSRF attacks. Store this in the user’s session and verify it when the callback is received

Security Best Practice: Always include a state parameter with a cryptographically random value. Verify this value matches when processing the callback to prevent cross-site request forgery (CSRF) attacks.

Step 2: User Authorizes the Application

When the user clicks the authorization link, they’re redirected to the authorization server. If not already logged in, they authenticate with their credentials. Then they see a consent screen showing:

- Which application is requesting access

- What permissions (scopes) are being requested

- Which account the access will be granted for

The user can approve or deny the request. If they approve, the authorization server generates an authorization code.

Step 3: Receive Authorization Code

After user approval, the authorization server redirects the user back to your redirect_uri with an authorization code:

https://your-app.com/callback?code=AUTHORIZATION_CODE&state=RANDOM_STATE_STRING

Important: The authorization code is short-lived (typically 10 minutes or less) and can only be used once. Exchange it immediately for an access token.

Step 4: Exchange Code for Access Token

Your server makes a POST request to the token endpoint, sending the authorization code along with your client credentials:

POST https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

client_id=CLIENT_ID&client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET&grant_type=authorization_code&code=AUTHORIZATION_CODE&redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL

This request must be made server-to-server; never expose your client secret in client-side code.

Step 5: Receive Access Token

If the authorization code is valid and hasn’t expired, the authorization server responds with tokens:

{

"access_token": "ACCESS_TOKEN",

"token_type": "bearer",

"expires_in": 2592000,

"refresh_token": "REFRESH_TOKEN",

"scope": "read",

"uid": 100101

}

Token Response Fields:

access_token: Use this to authenticate API requests. Store it securely and never expose it in URLs or client-side code.token_type: Usually"bearer", indicating how to use the token (in theAuthorizationheader).expires_in: Token lifetime in seconds (e.g., 2592000 = 30 days).refresh_token: Optional token used to obtain new access tokens without user interaction.scope: The permissions granted (may be a subset of requested scopes).

Your application is now authorized. Use the access token to make API requests on behalf of the user, within the granted scope, until the token expires or is revoked.

Complete Implementation Example

This example demonstrates a production-ready Express.js server implementing the full Authorization Code flow. It includes all security best practices: state parameter validation to prevent CSRF attacks, proper error handling for common OAuth 2 failure scenarios, automatic token refresh to maintain seamless user sessions, and secure token storage. The implementation handles the complete lifecycle from initial authorization request through token exchange, refresh, and API usage.

// Express.js example - OAuth 2 Authorization Code flow

const express = require('express');

const crypto = require('crypto');

const axios = require('axios');

const app = express();

const CLIENT_ID = process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_ID;

const CLIENT_SECRET = process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_SECRET;

const REDIRECT_URI = 'https://your-app.com/callback';

const AUTHORIZATION_URL = 'https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/authorize';

const TOKEN_URL = 'https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token';

// Store state values in session (use Redis in production)

const stateStore = new Map();

// Step 1: Redirect user to authorization server

app.get('/auth', (req, res) => {

// Generate cryptographically random state

const state = crypto.randomBytes(32).toString('hex');

stateStore.set(state, { timestamp: Date.now() });

// Build authorization URL

const authUrl = new URL(AUTHORIZATION_URL);

authUrl.searchParams.set('response_type', 'code');

authUrl.searchParams.set('client_id', CLIENT_ID);

authUrl.searchParams.set('redirect_uri', REDIRECT_URI);

authUrl.searchParams.set('scope', 'read write');

authUrl.searchParams.set('state', state);

res.redirect(authUrl.toString());

});

// Step 2-4: Handle callback and exchange code for token

app.get('/callback', async (req, res) => {

const { code, state, error } = req.query;

// Validate state parameter

if (!stateStore.has(state)) {

return res.status(400).send('Invalid state parameter');

}

stateStore.delete(state); // Use state only once

// Handle authorization denial

if (error) {

return res.status(400).send(`Authorization failed: ${error}`);

}

if (!code) {

return res.status(400).send('Authorization code missing');

}

try {

// Exchange authorization code for access token

// Use URLSearchParams to send form data, not JSON

const tokenResponse = await axios.post(TOKEN_URL,

new URLSearchParams({

grant_type: 'authorization_code',

code: code,

redirect_uri: REDIRECT_URI,

client_id: CLIENT_ID,

client_secret: CLIENT_SECRET

}), {

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded'

}

}

);

const { access_token, refresh_token, expires_in } = tokenResponse.data;

// Store tokens securely (use encrypted database in production)

// In this example, we'll store in session

req.session.accessToken = access_token;

req.session.refreshToken = refresh_token;

req.session.tokenExpiry = Date.now() + (expires_in * 1000);

res.redirect('/dashboard');

} catch (error) {

// Handle token exchange errors

if (error.response) {

const { error: errorCode, error_description } = error.response.data;

console.error('Token exchange failed:', errorCode, error_description);

if (errorCode === 'invalid_grant') {

// Authorization code expired or already used

return res.status(400).send('Authorization code expired. Please try again.');

} else if (errorCode === 'invalid_client') {

// Client credentials invalid

return res.status(500).send('Server configuration error');

}

}

res.status(500).send('Token exchange failed');

}

});

// Step 5-6: Use access token to make API requests

app.get('/api/droplets', async (req, res) => {

let accessToken = req.session.accessToken;

// Check if token expired

if (Date.now() >= req.session.tokenExpiry) {

// Refresh the token

try {

const refreshResponse = await axios.post(TOKEN_URL,

new URLSearchParams({

grant_type: 'refresh_token',

refresh_token: req.session.refreshToken,

client_id: CLIENT_ID,

client_secret: CLIENT_SECRET

}), {

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded'

}

}

);

accessToken = refreshResponse.data.access_token;

req.session.accessToken = accessToken;

req.session.tokenExpiry = Date.now() + (refreshResponse.data.expires_in * 1000);

} catch (error) {

// Refresh failed, redirect to re-authorize

return res.redirect('/auth');

}

}

try {

const apiResponse = await axios.get('https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets', {

headers: {

'Authorization': `Bearer ${accessToken}`

}

});

res.json(apiResponse.data);

} catch (error) {

if (error.response?.status === 401) {

// Token invalid, redirect to re-authorize

return res.redirect('/auth');

}

res.status(error.response?.status || 500).json({ error: 'API request failed' });

}

});

Key implementation details:

- State validation: Prevents CSRF attacks by verifying the state parameter matches what you sent

- Error handling: Handles authorization denial, expired codes, and invalid tokens

- Token refresh: Automatically refreshes expired tokens before making API requests

- Secure storage: Tokens stored in session (use encrypted database in production)

- One-time code use: Authorization codes are single-use; attempting to reuse them fails

Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE)

PKCE (pronounced “pixie”) is a security extension to the Authorization Code flow that prevents authorization code interception attacks. It’s essential for public clients (mobile apps, single-page applications) that cannot securely store client secrets.

Why PKCE Matters

Without PKCE, here’s the exact attack:

- You install a legitimate app (“Photo Editor”) and a malicious app (“Free Wallpapers”) on your phone

- The malicious app registers a custom URL scheme:

photoeditor://callback(pretending to be the legitimate app) - When you authorize the Photo Editor app, the authorization code gets sent to:

photoeditor://callback?code=ABC123 - The malicious app intercepts this URL (since it registered the same scheme) and steals the code

ABC123 - The malicious app exchanges the code for an access token using the legitimate app’s public client ID

- Result: The malicious app now has full access to your account

With PKCE:

- The legitimate Photo Editor generates a secret

code_verifier(e.g.,dBjftJeZ4CVP-mB92K27uhbUJU1p1r_wW1gFWFOEjXk) before starting OAuth - It creates a

code_challengeby hashing this verifier:SHA256(code_verifier)→E9Melhoa2OwvFrEMTJguCHaoeK1t8URWbuGJSstw-cM - The authorization URL includes:

&code_challenge=E9Melhoa2OwvFrEMTJguCHaoeK1t8URWbuGJSstw-cM - Even if the malicious app intercepts the authorization code, it can’t exchange it without the original

code_verifier - When the legitimate app exchanges the code, it sends:

&code_verifier=dBjftJeZ4CVP-mB92K27uhbUJU1p1r_wW1gFWFOEjXk - The authorization server hashes it, confirms it matches the challenge, and issues the token

- Result: The malicious app’s exchange attempt fails with

invalid_granterror

PKCE makes the authorization code useless without the secret only your app knows.

How PKCE Works

Step 1: Generate Code Verifier and Challenge

Before redirecting to the authorization server, your client generates:

- Code Verifier: A cryptographically random string (43-128 characters, URL-safe)

- Code Challenge: A transformation of the verifier (typically SHA256 hash, base64url-encoded)

// Example PKCE generation (conceptual example)

const codeVerifier = generateRandomString(43);

const codeChallenge = base64url(sha256(codeVerifier));

Step 2: Include Challenge in Authorization Request

Add the code challenge and method to your authorization URL:

https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/authorize?

response_type=code&

client_id=CLIENT_ID&

redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL&

code_challenge=CODE_CHALLENGE&

code_challenge_method=S256&

scope=read

Step 3: Send Verifier with Token Request

When exchanging the authorization code for a token, include the original code verifier:

POST https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token

client_id=CLIENT_ID&

grant_type=authorization_code&

code=AUTHORIZATION_CODE&

redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URL&

code_verifier=CODE_VERIFIER

Step 4: Server Validates

The authorization server:

- Hashes the

code_verifierusing the specified method (S256 = SHA256) - Compares it to the stored

code_challenge - Only issues a token if they match

Best Practice: Always use PKCE, even for confidential clients. It adds minimal complexity while significantly improving security. Most modern OAuth 2 libraries handle PKCE automatically.

Client Credentials Grant Type

The Client Credentials grant type enables machine-to-machine communication where no user is involved. The application authenticates using its own credentials and receives an access token for its service account.

When to Use Client Credentials

Use this grant type when:

- Your application needs to access its own resources (not user resources)

- You’re building server-to-server integrations

- No user interaction is required or possible

- You need to update application settings via API

Common Use Cases:

- Background jobs accessing APIs

- Microservices authenticating to each other

- Applications updating their own OAuth registration details

- Automated systems performing administrative tasks

Client Credentials Flow

The flow is straightforward since no user interaction is needed:

Step 1: Request Access Token

Make a POST request to the token endpoint with your client credentials:

POST https://oauth.example.com/token

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

grant_type=client_credentials&

client_id=CLIENT_ID&

client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET&

scope=read

Step 2: Receive Access Token

The authorization server validates your credentials and returns an access token:

{

"access_token": "ACCESS_TOKEN",

"token_type": "bearer",

"expires_in": 3600,

"scope": "read"

}

Note that refresh tokens are typically not issued for client credentials grants. Since no user is involved, the application can request a new access token directly whenever the current one expires, using the same client credentials.

Note: DigitalOcean does not currently support the client credentials grant type. This example uses a hypothetical authorization server for illustration purposes.

Device Code Grant Type

The Device Code grant type enables authorization on devices that lack browsers or have limited input capabilities. Users authorize on a separate device (like their phone or computer) while the constrained device polls for the authorization result.

When to Use Device Code Flow

Use this grant type for:

- Smart TVs and streaming devices

- IoT devices without displays

- Game consoles

- Printers and other embedded systems

- Command-line tools running on headless servers

Device Code Flow

Step 1: Request Device and User Codes

The device makes a POST request to the device authorization endpoint:

POST https://oauth.example.com/device

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

client_id=CLIENT_ID&

scope=read

Step 2: Receive Device and User Codes

The authorization server responds with codes the user needs to enter:

{

"device_code": "IO2RUI3SAH0IQuESHAEBAeYOO8UPAI",

"user_code": "RSIK-KRAM",

"verification_uri": "https://example.okta.com/device",

"verification_uri_complete": "https://example.okta.com/device?user_code=RSIK-KRAM",

"interval": 10,

"expires_in": 1600

}

Response Fields:

device_code: Used by the device to poll for authorization statususer_code: Short code the user enters (often displayed asRSIK-KRAMfor readability)verification_uri: URL where the user enters the codeverification_uri_complete: Complete URL with user code pre-filled (useful for QR codes)interval: Minimum seconds between polling requestsexpires_in: How long the codes remain valid

Step 3: Display Codes to User

The device displays the user code and verification URL (often as a QR code). The user:

- Opens the verification URL on a device with a browser

- Enters the user code

- Authenticates and approves the authorization request

Step 4: Device Polls for Token

While the user authorizes, the device polls the token endpoint:

POST https://oauth.example.com/token

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

grant_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:grant-type:device_code&

device_code=IO2RUI3SAH0IQuESHAEBAeYOO8UPAI&

client_id=CLIENT_ID

Polling Responses:

authorization_pending: User hasn’t approved yet; continue pollingslow_down: Polling too frequently; increase intervalaccess_denied: User denied the request; stop pollingexpired_token: Codes expired; start over- Success: Returns access token and refresh token

Best Practice: Respect the interval value and implement exponential backoff. Don’t poll more frequently than the server specifies, as this wastes resources and may trigger rate limiting.

Note: DigitalOcean does not currently support the device code grant type. This example uses a hypothetical authorization server for illustration purposes.

Using Access Tokens

Once you have an access token, use it to authenticate API requests. The standard method is including the token in the Authorization header using the Bearer authentication scheme.

Making Authenticated API Requests

Here’s an example using curl:

curl -X GET \

-H "Authorization: Bearer ACCESS_TOKEN" \

https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets

For POST requests with a JSON body:

curl -X POST \

-H "Authorization: Bearer ACCESS_TOKEN" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name":"example-droplet","region":"nyc1","size":"s-1vcpu-1gb","image":"ubuntu-22-04"}' \

https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets

Token Validation and Error Handling

The resource server validates the access token on every request. Here are the actual HTTP responses you’ll encounter:

Success Response (200 OK):

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

{

"droplets": [...],

"meta": {...}

}

Token Missing or Invalid (401 Unauthorized):

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

Content-Type: application/json

WWW-Authenticate: Bearer error="invalid_token", error_description="The access token expired"

{

"id": "unauthorized",

"message": "Unable to authenticate you"

}

Insufficient Scope (403 Forbidden):

HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

Content-Type: application/json

{

"id": "forbidden",

"message": "You do not have access to the requested resource"

}

Handling Token Expiration:

When you receive 401 Unauthorized, check the response body for the specific error. Common scenarios:

Token expired: Error description mentions “expired” or “invalid_token”

- If you have a refresh token: Exchange it for a new access token

- If no refresh token: Redirect user through authorization flow again

Token revoked: User or service revoked the token

- Clear stored tokens and restart authorization flow

Token malformed: Token format is incorrect

- Check that you’re sending it in the

Authorization: Bearer TOKENheader format - Verify the token wasn’t truncated or modified

Security Note: Never log access tokens, include them in URLs, or expose them in client-side JavaScript. Treat access tokens like passwords: store them securely and transmit them only over HTTPS.

Refresh Token Flow

Refresh tokens enable applications to obtain new access tokens without requiring user interaction. This provides a seamless user experience while maintaining security through token expiration.

When Access Tokens Expire

Access tokens have limited lifespans (typically 1 hour to 30 days, depending on the service). When a token expires:

- API requests return

401 Unauthorized - Users would otherwise need to re-authorize frequently

- Refresh tokens solve this by enabling automatic token renewal

How Refresh Tokens Work

Step 1: Request New Access Token

When your access token expires, exchange the refresh token for a new one:

POST https://cloud.digitalocean.com/v1/oauth/token

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

grant_type=refresh_token&

client_id=CLIENT_ID&

client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET&

refresh_token=REFRESH_TOKEN

Step 2: Receive New Tokens

The authorization server validates the refresh token and issues new tokens:

{

"access_token": "NEW_ACCESS_TOKEN",

"token_type": "bearer",

"expires_in": 2592000,

"refresh_token": "NEW_REFRESH_TOKEN",

"scope": "read"

}

Token Rotation: Some services issue a new refresh token with each refresh (token rotation). Always save the new refresh token, as the old one may be invalidated. Other services reuse the same refresh token until it’s explicitly revoked.

Refresh Token Best Practices

- Store refresh tokens securely: Use encrypted storage, never in plaintext

- Handle refresh token expiration: Refresh tokens can also expire; redirect users to re-authorize if needed

- Revoke unused tokens: If a user logs out, revoke both access and refresh tokens

- Monitor token usage: Unusual refresh patterns may indicate compromised tokens

When to Use OAuth 2

Understanding when OAuth 2 is the right choice helps you avoid over-engineering or security pitfalls. This section covers appropriate use cases and scenarios where OAuth 2 might not be the best fit.

Use OAuth 2 For

1. Third-Party App Integrations

Real examples:

- Zapier accessing your Gmail to create automated workflows (uses OAuth to read/send emails without your password)

- Trello Power-Ups connecting to Google Drive (OAuth grants access to specific folders only)

- Social media scheduling tools (Buffer, Hootsuite) posting to Twitter/LinkedIn on your behalf

- Cloud backup services (Backblaze, Carbonite) syncing from Dropbox/OneDrive

Implementation: Authorization Code flow with read and write scopes

2. “Connect Your Account” Features

Real examples:

- E-commerce checkout offering “Sign in with Amazon” to pre-fill shipping addresses

- Music streaming apps importing playlists from Spotify using their API

- Fitness apps syncing workout data from Apple Health or Google Fit

- Calendar aggregators (Calendly, Fantastical) displaying events from multiple calendar services

Implementation: Authorization Code flow, typically with OpenID Connect for identity + data access

3. Mobile App API Access

Real examples:

- Instagram mobile app accessing user photos, posting content, retrieving feed data

- Banking apps accessing transaction data from backend APIs

- Delivery apps (DoorDash, Uber Eats) accessing user location and order history

Implementation: Authorization Code with PKCE (no client secret stored in app)

4. Server-to-Server Automation

Real examples:

- CI/CD pipelines (GitHub Actions, CircleCI) deploying to DigitalOcean using API tokens

- Monitoring tools (Datadog, New Relic) accessing infrastructure APIs to collect metrics

- Backup scripts running on cron jobs to archive data via API

Implementation: Client Credentials flow (no user interaction)

5. IoT and Smart Devices

Real examples:

- Smart home hubs (SmartThings, Home Assistant) controlling Philips Hue lights

- Smart TVs accessing Netflix, YouTube, Disney+ accounts

- Digital photo frames displaying Google Photos albums

Implementation: Device Code flow (user authorizes on phone/computer)

Don’t Use OAuth 2 For

1. Your Own Application’s Login System

OAuth 2 is designed for third-party authorization, not for authenticating users of your own application. When users log into your app with credentials you manage, you don’t need OAuth 2.

Why not use OAuth 2 here:

- OAuth 2 adds unnecessary complexity when you control both the client and authorization server

- You already have the user’s credentials, so there’s no need for token-based delegation

- Traditional authentication (username/password with bcrypt hashing) is simpler and more appropriate

- OAuth 2 requires redirect flows and token management that aren’t needed for direct authentication

- Session-based authentication is more efficient for your own users

What to use instead:

For your own login system, use standard authentication patterns:

// CORRECT: Simple authentication for your own users

app.post('/login', async (req, res) => {

const user = await User.findOne({ email: req.body.email });

if (!user) {

return res.status(401).json({ error: 'Invalid credentials' });

}

const valid = await bcrypt.compare(req.body.password, user.passwordHash);

if (valid) {

req.session.userId = user.id; // Simple session-based auth

res.json({ success: true });

} else {

res.status(401).json({ error: 'Invalid credentials' });

}

});

When OAuth 2 makes sense for login:

Use OAuth 2 only when offering “Sign in with Google/GitHub” social login, where you’re delegating authentication to a third-party provider:

// CORRECT: OAuth 2 for social login (third-party authentication)

app.get('/auth/google', passport.authenticate('google', {

scope: ['profile', 'email']

}));

2. Internal Microservices Communication

For services within your infrastructure:

- Use mTLS (mutual TLS certificates) for service-to-service authentication

- Use service mesh (Istio, Linkerd) with built-in identity

- Use API Gateway with internal API keys

- OAuth 2 adds unnecessary complexity when you control both client and server

3. Simple API Keys Are Sufficient

Use API keys instead of OAuth when:

- Accessing public data that doesn’t require user permission (weather APIs, stock prices)

- Your API has a flat permission model (no user-specific data)

- You’re providing access to services, not user resources

Example: OpenWeatherMap API, CoinGecko API, public transportation APIs

4. Real-Time Communication

WebSockets, WebRTC, or gRPC streams are better suited for:

- Live chat applications

- Multiplayer games

- Real-time collaboration tools

- Streaming video/audio

Use OAuth 2 to establish the initial session, then switch to connection-based protocols.

Common OAuth 2 Implementation Gotchas

Avoid these common mistakes when implementing OAuth 2:

1. Insecure Redirect URI Validation

Problem: Accepting redirect URIs that don’t exactly match registered URIs, or using wildcards.

Solution: Validate redirect URIs exactly, character-for-character. Register separate URIs for each environment:

// WRONG - Wildcard allows attacker.com

const ALLOWED_REDIRECTS = ['https://*.myapp.com/callback'];

// CORRECT - Explicit list

const ALLOWED_REDIRECTS = [

'https://app.myapp.com/callback',

'https://staging.myapp.com/callback',

'http://localhost:3000/callback' // Development only

];

if (!ALLOWED_REDIRECTS.includes(redirectUri)) {

throw new Error('redirect_uri_mismatch');

}

Common mistakes:

- Trailing slash differences:

https://app.com/callback≠https://app.com/callback/ - Protocol matters:

http://≠https:// - Port matters:

http://localhost:3000≠http://localhost:8080

2. Missing State Parameter Validation

Problem: Not validating the state parameter enables CSRF attacks where attackers trick users into authorizing malicious applications.

How the attack works:

- Attacker starts OAuth flow for victim’s account

- Attacker captures the authorization URL with their state value

- Attacker tricks victim into clicking the link (via phishing email)

- Victim authorizes, thinking they’re logging into attacker’s app

- Authorization code gets sent to attacker’s redirect URI

- Attacker’s app now has access to victim’s account

Solution: Generate cryptographically random state, validate it matches:

const crypto = require('crypto');

// Generate state

const state = crypto.randomBytes(32).toString('hex');

req.session.oauthState = state; // Store in session

// Validate state in callback

if (req.query.state !== req.session.oauthState) {

return res.status(403).send('Possible CSRF attack detected');

}

delete req.session.oauthState; // Use once

3. Storing Tokens Insecurely

Problem: Storing access tokens in localStorage, cookies without HttpOnly flag, or logging them.

Solution - Web Applications:

// WRONG - Vulnerable to XSS attacks

localStorage.setItem('access_token', token);

sessionStorage.setItem('access_token', token);

// CORRECT - Server-side session with HttpOnly cookies

res.cookie('session_id', sessionId, {

httpOnly: true, // JavaScript can't access it

secure: true, // HTTPS only

sameSite: 'lax', // CSRF protection

maxAge: 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000 // 24 hours

});

// Store the actual token server-side in Redis/database, indexed by session_id

Solution - Mobile Applications:

// iOS - Use Keychain

import Security

let query: [String: Any] = [

kSecClass as String: kSecClassGenericPassword,

kSecAttrAccount as String: "oauth_access_token",

kSecValueData as String: token.data(using: .utf8)!,

kSecAttrAccessible as String: kSecAttrAccessibleWhenUnlockedThisDeviceOnly

]

SecItemAdd(query as CFDictionary, nil)

// Android - Use EncryptedSharedPreferences (API 23+)

import androidx.security.crypto.EncryptedSharedPreferences

import androidx.security.crypto.MasterKey

val masterKey = MasterKey.Builder(context)

.setKeyScheme(MasterKey.KeyScheme.AES256_GCM)

.build()

val sharedPreferences = EncryptedSharedPreferences.create(

context,

"oauth_prefs",

masterKey,

EncryptedSharedPreferences.PrefKeyEncryptionScheme.AES256_SIV,

EncryptedSharedPreferences.PrefValueEncryptionScheme.AES256_GCM

)

sharedPreferences.edit()

.putString("access_token", token)

.apply()

Never do this:

- Don’t log tokens:

console.log(accessToken) - Don’t store in plain cookies without HttpOnly flag

- Don’t commit tokens to version control

- Don’t include tokens in error messages or stack traces

4. Not Handling Token Expiration

Problem: Assuming tokens never expire, leading to sudden authentication failures.

Solution: Check token expiry before each request, refresh proactively:

async function makeAuthenticatedRequest(url) {

// Check if token expires in next 5 minutes

const expiryBuffer = 5 * 60 * 1000; // 5 minutes in milliseconds

const tokenExpiry = new Date(req.session.tokenExpiry);

if (Date.now() + expiryBuffer >= tokenExpiry.getTime()) {

// Token expired or about to expire, refresh it

await refreshAccessToken();

}

// Now make the request with fresh token

return axios.get(url, {

headers: { 'Authorization': `Bearer ${req.session.accessToken}` }

});

}

5. Scope Creep

Problem: Requesting broad permissions reduces user trust and authorization rates.

// WRONG - Requesting unnecessary permissions

const scopes = 'read write delete admin user:email repo';

// User sees: "This app wants to delete your data and access all repos"

// Authorization rate: ~40%

// CORRECT - Request minimum required

const scopes = 'read user:email';

// User sees: "This app wants to read your data and email"

// Authorization rate: ~85%

Progressive permissions

Request additional scopes only when needed:

- Initial login: Request

readanduser:emailonly - When user clicks “Export Data”: Request

read:backupscope - When user enables auto-posting: Request

write:postsscope

6. Ignoring PKCE for Public Clients

Problem: Not using PKCE for mobile apps or SPAs leaves authorization codes vulnerable to interception.

Solution: Always implement PKCE for public clients:

- Mobile apps: Mandatory (no way to securely store client secret)

- Single-Page Apps (SPAs): Mandatory (JavaScript can be inspected)

- Desktop apps: Recommended (executables can be decompiled)

- Server-side apps: Recommended (defense-in-depth)

Most OAuth 2 libraries handle PKCE automatically (Passport.js, NextAuth.js, AppAuth iOS/Android).

Troubleshooting Common OAuth 2 Issues

When OAuth 2 flows fail, the error messages can be cryptic. Here’s how to diagnose and fix the most common problems:

“invalid_client” Error

What it means: The authorization server doesn’t recognize your client ID or client secret.

Common causes:

- Client ID or secret copied incorrectly

- Client secret exposed and regenerated (old secret no longer works)

- Application not registered with the service

How to fix:

Step 1: Verify Client ID

# Print your current client ID

echo "Current CLIENT_ID: $OAUTH_CLIENT_ID"

# Compare with developer portal:

# - DigitalOcean: https://cloud.digitalocean.com/account/api/applications

# - GitHub: https://github.com/settings/developers

# - Google: https://console.cloud.google.com/apis/credentials

Look for:

- Leading/trailing whitespace in your .env file

- Copy-paste errors (some characters look similar:

0vsO,1vsl) - Client ID from wrong environment (dev vs production)

Step 2: Check Client Secret

// Add temporary logging (REMOVE after debugging)

console.log('Client Secret length:', process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_SECRET?.length);

console.log('First 4 chars:', process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_SECRET?.substring(0, 4));

// Compare with developer portal (first few characters)

If the secret was regenerated:

- Go to your service’s developer portal

- Look for “Regenerate Secret” or “Reset Secret” button

- Check if there’s a timestamp showing recent regeneration

- Copy the NEW secret and update your

.envfile - Restart your application

Step 3: Verify Application Status

Some services require approval:

- Check if your app is in “Pending” or “Under Review” status

- Verify you’ve completed all required fields (logo, privacy policy URL)

- Check your email for approval/rejection notifications

Example error response:

{

"error": "invalid_client",

"error_description": "Client authentication failed"

}

“invalid_grant” Error

What it means: The authorization code is invalid, expired, or already used.

Common causes:

- Authorization code expired (typically 10 minutes)

- Code already exchanged for a token (codes are single-use)

- Code doesn’t match the redirect URI used in the authorization request

- Clock skew between your server and authorization server

How to fix:

Scenario 1: Code Expired

// WRONG - Queuing code for later processing

app.get('/callback', (req, res) => {

const { code } = req.query;

jobQueue.add({ code }); // Process in 2 minutes

res.send('Please wait...');

});

// CORRECT - Exchange immediately

app.get('/callback', async (req, res) => {

const { code } = req.query;

const tokens = await exchangeCodeForToken(code); // Do it NOW

req.session.tokens = tokens;

res.redirect('/dashboard');

});

Timing example:

- 10:00:00 AM - User authorizes, code generated

- 10:09:30 AM - You exchange code - Success

- 10:10:01 AM - Code expires

- 10:11:00 AM - Another exchange attempt -

invalid_grant

Scenario 2: Redirect URI Mismatch

// Authorization request

const authUrl = `${AUTH_URL}?redirect_uri=https://app.com/callback`;

// Token exchange - MUST use EXACT same redirect_uri

const params = new URLSearchParams({

code: code,

redirect_uri: 'https://app.com/callback', // Must match exactly

// Even trailing slash matters!

});

// These would cause invalid_grant:

// redirect_uri: 'https://app.com/callback/' (extra slash)

// redirect_uri: 'https://app.com/oauth/callback' (different path)

// redirect_uri: 'http://app.com/callback' (http vs https)