This post was written by Aditya Maru, co-founder of Blacksmith, offering verticalized CI cloud infrastructure. We found their use case for Tailscale Services clever and instructive, so we’re sharing this post from their blog on our site, too.

TL;DR: We built a transparent proxy that routes GitHub traffic through an alternate network path with direct GitHub peering, giving our runners defence-in-depth against ISP routing failures. No code changes required for customers—GitHub Actions interact with GitHub exactly as they used to. This proxy uses the newly announcedTailscale Services for secure load balancing andSquid for high-performance proxying and caching.

The wake-up call

On Th…

This post was written by Aditya Maru, co-founder of Blacksmith, offering verticalized CI cloud infrastructure. We found their use case for Tailscale Services clever and instructive, so we’re sharing this post from their blog on our site, too.

TL;DR: We built a transparent proxy that routes GitHub traffic through an alternate network path with direct GitHub peering, giving our runners defence-in-depth against ISP routing failures. No code changes required for customers—GitHub Actions interact with GitHub exactly as they used to. This proxy uses the newly announcedTailscale Services for secure load balancing andSquid for high-performance proxying and caching.

The wake-up call

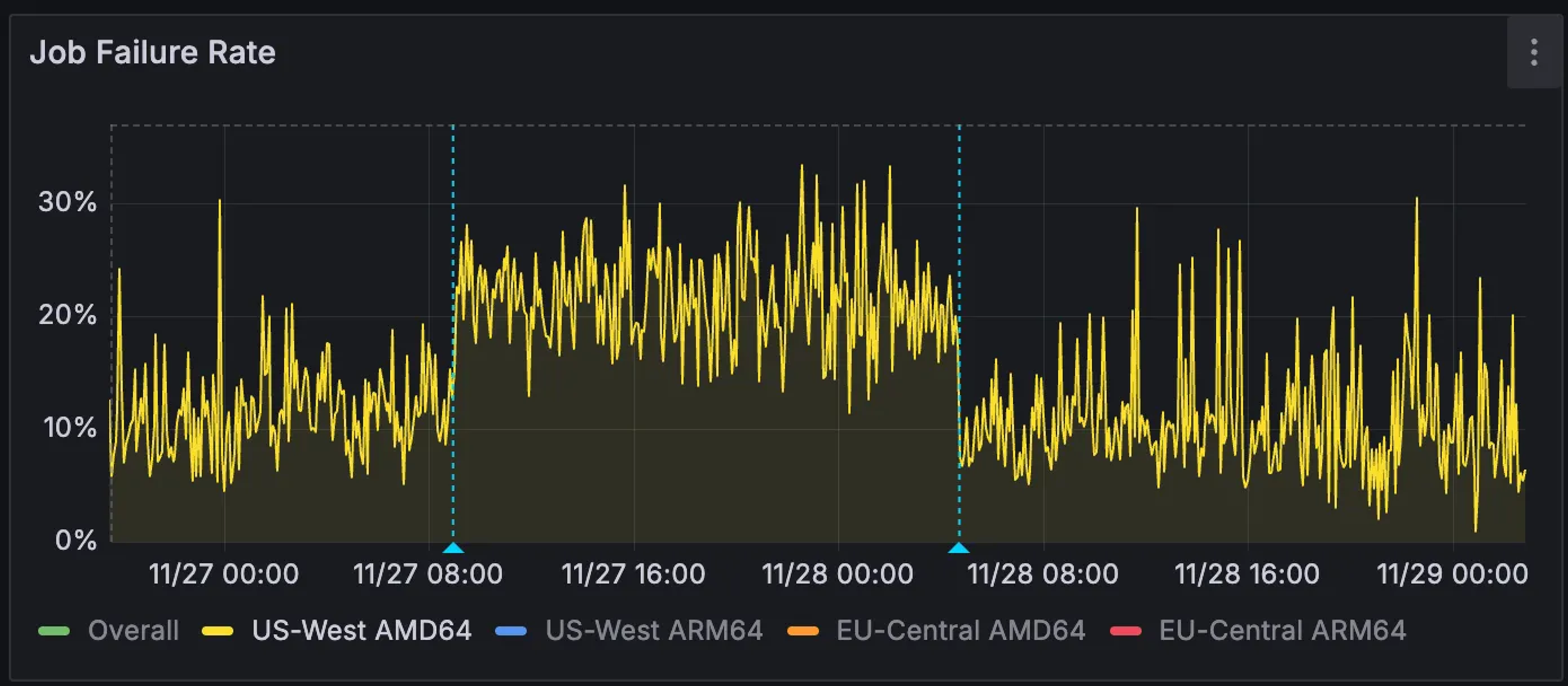

On Thanksgiving day, we woke up to an outage: GitHub Actions jobs running on Blacksmith’s infrastructure were not able to check out repositories. A large percentage of CI (continuous integration) jobs also interact with other GitHub endpoints, such as packages, API, and ghcr.io, and they were all timing out as well. The actions/checkout steps that normally complete in seconds were timing out after two minutes.

The error messages reported in our support issues offered little insight:

Failed to connect to github.com port 443 after 134053 ms: Couldn't connect to server

The problem wasn’t with GitHub. It wasn’t in the infrastructure stack that we had direct control over. It was somewhere in between: an upstream ISP, with degraded routing from one of GitHub’s edge nodes. Connections from our datacenter were experiencing five to 20-second HTTP stalls on roughly 7-10% of requests. Meanwhile, the exact same operations from other regions, hitting the same set of GitHub edge nodes, were performing normally.

At our scale, when 7% of GitHub connections stall, that’s dozens of jobs failing every minute.

Image via Blacksmith

Image via Blacksmith

Why we couldn’t just "fix the network"

The instinctive response is to find the bad ISP, call them, escalate, and get the routing fixed. That’s easier said than done when your data center uses a blend of ISPs, and you have no visibility into which one is degraded. We had to disable them one by one, check if the problem reproduced, then repeat until we found the culprit. That process took 16 hours. But even after identifying the problematic ISP, routing issues like peering disputes, BGP misconfigurations, and congested links can take days to fully resolve. These aren’t problems you solve with a phone call on a holiday weekend.

We needed a disaster recovery solution that:

- Works immediately when routing degrades

- Requires zero changes from customers

- Only affects GitHub traffic, while everything else stays on the default network path

Transparent proxying with iptables

The goal was to be able to flip a switch and route GitHub-bound traffic from our VMs through a pool of proxies, running in a network stack, with direct GitHub peering. During an ISP degradation in our network stack, this would allow us to bypass the problematic hops entirely and reach GitHub over a well-maintained network path.

Here’s what we built:

When a packet leaves a VM destined for a GitHub IP, the kernel rewrites the destination to our ProxyManager process running on the bare metal host. The ProxyManager then uses the SO_ORIGINAL_DST socket option to recover where the packet was actually headed, opens an HTTP CONNECT tunnel through Squid, and pipes bytes back and forth. Our cluster of Squid proxies sit inside our tailnet and are addressable by a single stable IP provided by a Tailscale Service. The key insight: we only intercept traffic destined for GitHub. Everything else takes the normal path.

To do this efficiently, we use an ipset. This is a Linux kernel data structure that stores a set of IP addresses or network ranges and lets you match packets against the entire set in O(1) time. Without ipset, you’d need a separate iptables rule for each of GitHub’s ~50 IP ranges, and the kernel would check each rule sequentially. With ipset, you load all the ranges into a single set, and matching a packet is a single hash lookup. It’s the difference between a linear scan and a hash table. We populate our ipset with GitHub’s published CIDRs.

When the ranges change, we swap the ipset atomically. Packets in flight continue matching against the old set until the swap completes, then instantly start matching against the new one. With this mechanism, there are no dropped connections and no race conditions.

Tailscale Services: load balancing without the load balancer

The traditional approach to implementing this fix would be: put a load balancer (HAProxy, NGINX, a cloud provider’s network load balancer) in front of the Squid pool, expose a static IP, and configure agents to connect to that IP.

We did something different. Tailscale Services gave us load balancing, health checking, and encryption, without running a separate load balancer.

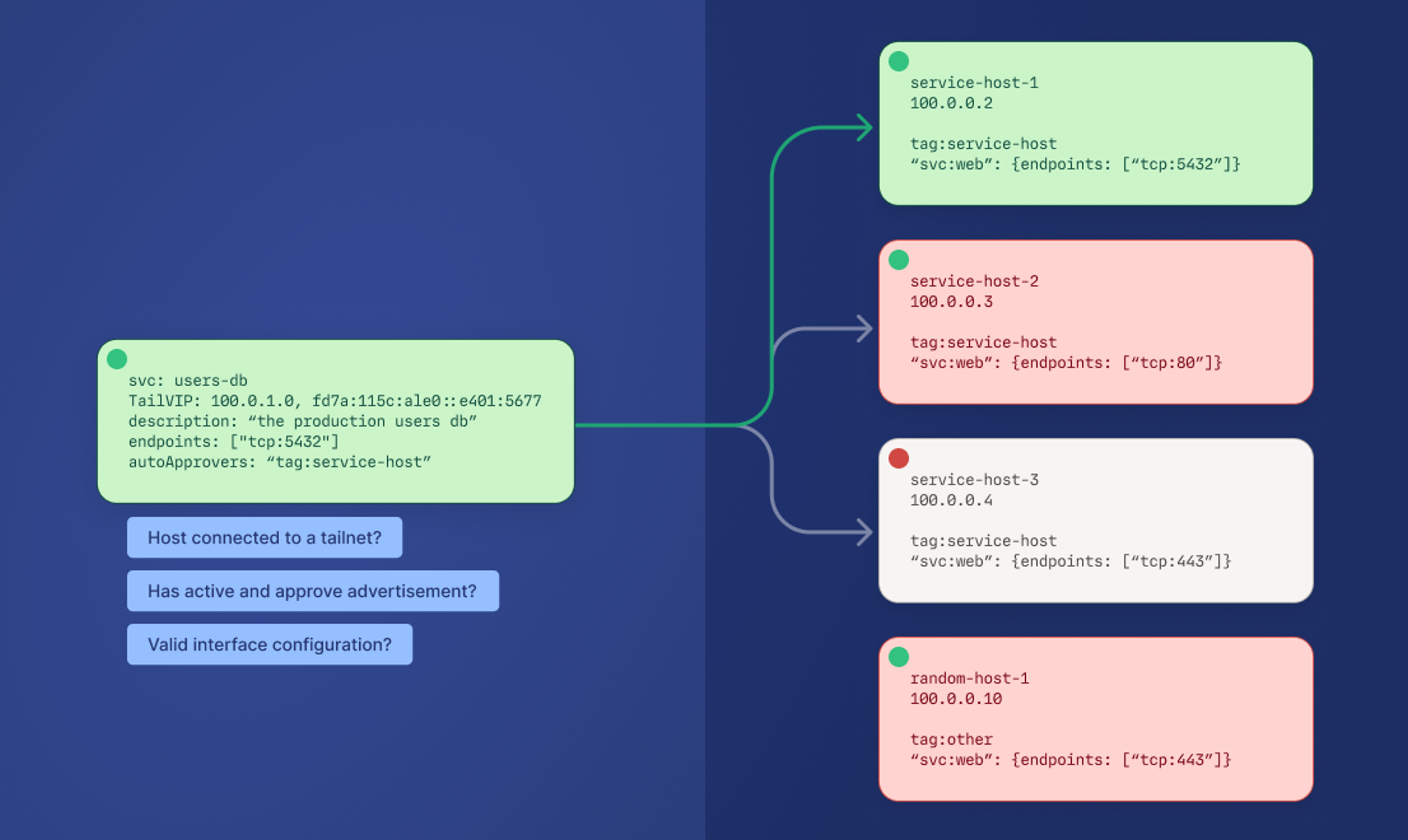

Tailscale Services performs a set of validations—including interface, connectivity, state, and tags—to provide intelligent routing, which can replace traditional load balancing.

Tailscale Services performs a set of validations—including interface, connectivity, state, and tags—to provide intelligent routing, which can replace traditional load balancing.

Each Squid instance registers itself with the service:

That’s it. The instance is now part of the git-proxy service. Tailscale handles:

- Health checking: Unhealthy backends are automatically removed

- Load distribution: Traffic spreads across available instances

- Encryption: All traffic flows over WireGuard tunnels

- Authentication: Only devices in our Tailnet can reach the service

From the agent’s perspective, it just connects to git-proxy.tailnet.ts.net:443. No IP addresses to manage. No certificates to rotate. No security groups needing holes punched.

The Squid instances have no public IP addresses for proxy traffic. They’re only reachable via Tailscale. Even if someone discovered the proxy, they couldn’t connect without being on our tailnet.

What’s next?

We now have a disaster recovery story for GitHub connectivity. When an ISP has a bad day, traffic automatically flows through the proxy. Customers don’t notice. Jobs complete. That’s the baseline we wanted. We’re actively load testing the proxy, so we’re better prepared for when this happens again.

The architecture is flexible enough that we could extend it to other critical services if needed. ECR, Docker Hub, package registries—anything that uses a known set of IPs could be routed through a similar proxy in a pinch.