Motivation

Embedding model inference often struggles with efficiency when serving large volumes of short requests—a common pattern in search, retrieval, and recommendation systems. At Voyage AI by MongoDB, we call these short requests queries, and other requests are called documents. Queries typically must be served with very low latency (typically 100–300 ms).

Queries are typically short, and their token-length distribution is highly skewed. As a result, query inference tends to be memory-bound rather than compute-bound. Query traffic is pretty spiky, so autoscaling is too slow. In sum, serving many short requests sequentially is highly inefficient.

In this blog post, we explore how batching can be used to serve queries more efficiently. We first discuss padding removal in…

Motivation

Embedding model inference often struggles with efficiency when serving large volumes of short requests—a common pattern in search, retrieval, and recommendation systems. At Voyage AI by MongoDB, we call these short requests queries, and other requests are called documents. Queries typically must be served with very low latency (typically 100–300 ms).

Queries are typically short, and their token-length distribution is highly skewed. As a result, query inference tends to be memory-bound rather than compute-bound. Query traffic is pretty spiky, so autoscaling is too slow. In sum, serving many short requests sequentially is highly inefficient.

In this blog post, we explore how batching can be used to serve queries more efficiently. We first discuss padding removal in modern inference engines, a key technique that enables effective batching. We then present practical strategies for forming batches and selecting an appropriate batch size. Finally, we walk through the implementation details and share the resulting performance improvements: a 50% reduction in GPU inference latency—despite using 3X fewer GPUs.

Padding removal makes effective batching possible

Given the patterns of query traffic, one straightforward idea is: can we batch them to improve inference efficiency? Padding removal, supported in inference engines like vLLM and SGLang, makes efficient batching possible.

Most inference engines accept requests in the form (B, S), where B is the sequence number in the batch, and S is the maximum sequence length. Sequences should be padded to the max sequence length so that tensors line up. But that convenience comes at a cost: padding tokens do no useful work but still consume compute and memory bandwidth, so latency scales with B × S instead of the actual token count. With serving large volumes of short requests, this wastes a large share of compute and can inflate tail latency.Padding removal and variable-length processing fix this by concatenating all active sequences into one long "super sequence" of length T = Σtoken_count_i, where token_count_i is the token count in sequence i. Inference engines like vLLM and SGLang can process this combined sequence. Attention masks and position indices ensure that each sequence only attends to its own tokens. As a result, inference time now tracks T rather than B × S, aligning GPU work with what matters.

Proposal: token-count-based batching

In Voyage AI, we proposed and built token-count-based batching, batching queries (short requests) by total token count in the batch (Σtoken_count_i), rather than by total request count or arbitrary time windows.

Time-window batching is inefficient when serving many short requests. Time-window batching swings between under- and over-filled batches depending on traffic. A short window keeps latency low but produces small, under-filled batches; a long window improves utilization but adds queueing delay. Traffic is bursty, so a single window size oscillates between under- and over-filling. Time-window batching introduces variability in resource utilization, causing the system to shift between memory-bound and compute-bound operations. Request-count batching has similar problems.

Figure 1. Request-number-based batching VS token-count-based batching.

Token-count batching aligns the batch size (total token count in the batch) with the actual compute required. When many queries arrive close together, we group them by token counts so the GPU processes a larger combined workload in a single forward pass. Based on our experiment, token-count-based batching amortizes fixed costs, reduces per-request latency and cost, and increases throughput and model flops utilization (MFU).

What is the optimal batch size?

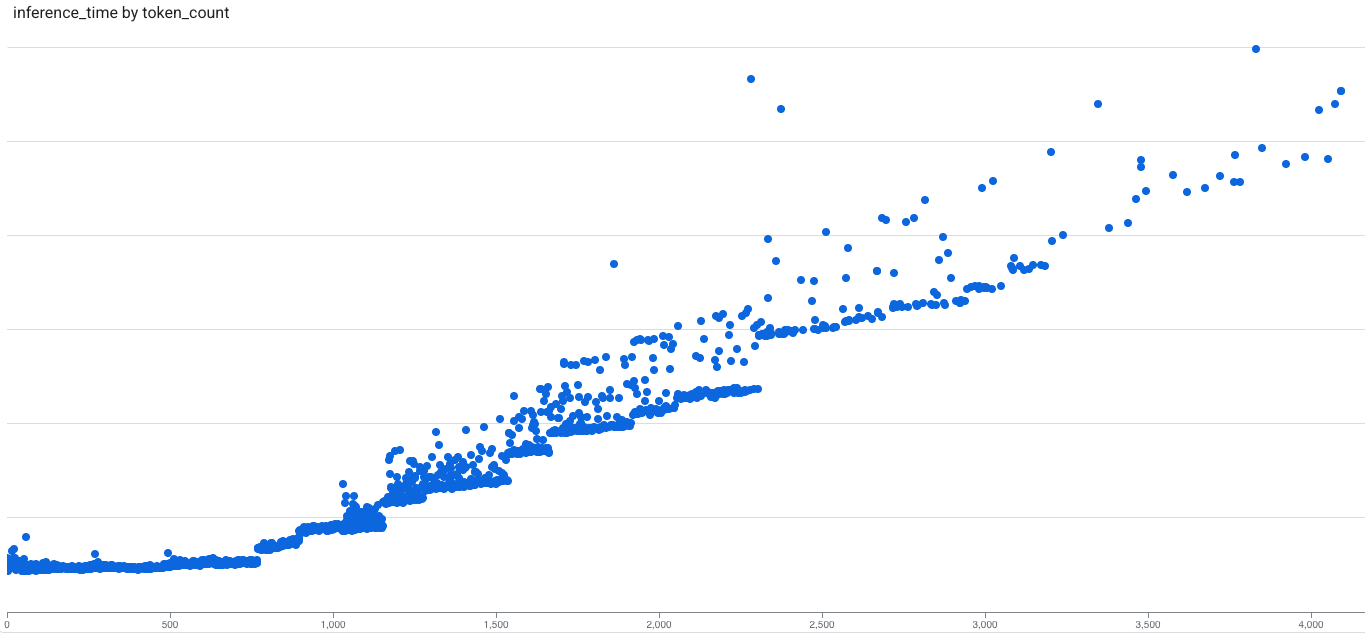

Our inference-latency-vs-token-count profiling of query inference shows a clear pattern: latency is approximately flat up to a threshold (saturation point) and then becomes approximately linear. For small requests, fixed per-request overheads (like GPU scheduling, memory movement, pooling and normalization, etc.) dominate, and latency stays nearly constant; beyond that point, latency scales with token count. The threshold (saturation point) depends on factors like the model architecture, inference engines, and GPU. For our voyage-3 model running on A100, the threshold is about 600 tokens.

Figure 2. Inference latency vs token count for Voyage-3 on A100.

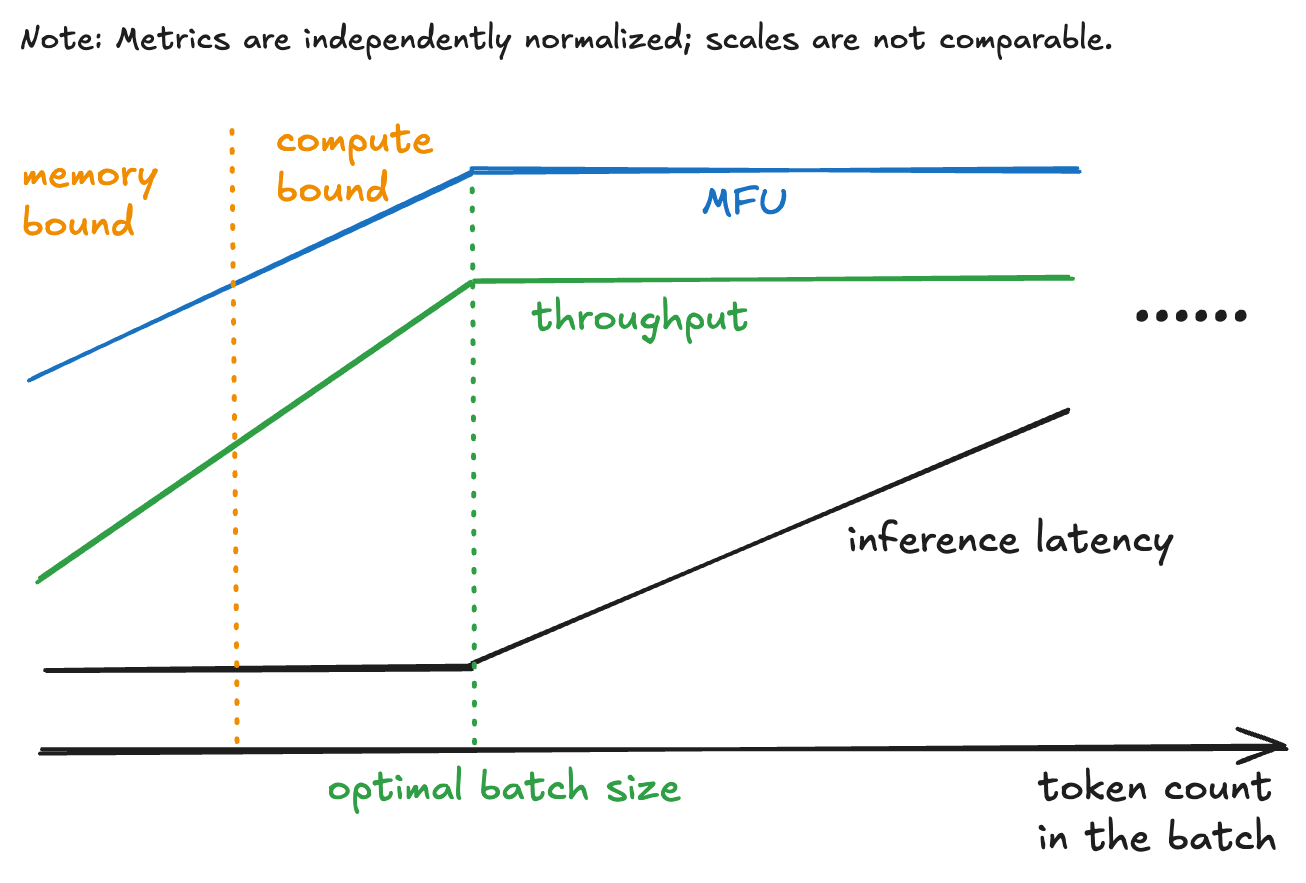

Based on the data of inference latency vs token count, we can analyze FLOPs Utilization (MFU) vs. token count and throughput vs. token count, which are shown in the following graph. We observe that Model FLOPs Utilization (MFU) and throughput scale approximately linearly with token count until reaching a saturation point. Most of our queries inferences are in the memory-bound zone, far away from the saturation point.

Figure 3. Approximated diagram of MFU/throughput/inference latency vs token count.

Batching short requests can move the inference from memory-bound to compute-bound. If we choose the saturation point in Figure 3 as the batch size (total token count in the batch), the latency and throughput/MFU can be balanced and optimized.

Queue design: enabling token-count-based batching

Token-count–based batching needs a data system that does more than simple FIFO delivery. The system has to attach an estimated token_count to each request, peek across pending requests, and then atomically claim a subset whose total tokens fit the optimal batch size (Σtoken_count_i ≤ optimal_batch_size). Without these primitives, we either underfill the GPU—wasting fixed overheads—or overfill it and spike tail latency.

General-purpose brokers like RabbitMQ and Kafka are excellent at durability, fan-out, and delivery, but their batching knobs are message count/bytes, not tokens. RabbitMQ’s prefetch is request-count-based, and messages are pushed to consumers, so there’s no efficient way to peek and batch requests by Σtoken_count_i. Kafka batches by bytes/messages within a partition; token count varies with text and tokenizer, so there is no efficient way to batch requests by Σtoken_count_i.

So there are two practical paths to make token-count-based batching work. One is to place a lightweight aggregator in front of Kafka/RabbitMQ that consumes batches by token counts and then dispatches batches to model servers. The other is to use a store that naturally supports fast peek + conditional batching—for example, Redis with Lua script. In our implementation, we use Redis because it lets us atomically “pop up to the optimal batch size” and set per-item TTLs within a single lua script call. Whatever we choose, the essential requirement is the same: the queue must let our system see multiple pending items, batch by Σtoken_count_i, and claim them atomically to keep utilization stable and latency predictable.

Our system enqueues each embedding query request into a Redis list as:

Code Snippet

Model servers call lua script atomically to fetch a batch of requests until the optimal batch size is reached. The probability of Redis losing data is very low. In the rare case that it does happen, users may receive 503 Service Unavailable errors and can simply retry. When QPS is low, batches are only partially filled and GPU utilization remains low, but latency still improves.

Figure 4. Batching implementation.

Results

We ran a production experiment on the Voyage-3-Large model serving, comparing our new pipeline (query batching + vLLM) against our old pipeline (no batching + Hugging Face Inference). We saw a 50% reduction in GPU inference latency—despite using 3X fewer GPUs.

We gradually onboarded 7+ models to the above query batching solution, and saw the following results (note that these results are based on our specific implementations of the “new” and “old” pipelines, and are not necessarily generalizable):

vLLM reduces GPU inference time by up to ~20 ms for most of our models 1.

Throughput improved by up to 8X by batching 1.

Some model servers saw P90 end-to-end latency drop by 60+ ms. The proposed solution can lower queuing time when resources are tight. 1.

By batching, we can have better P90 e2e latency during spikes, even with fewer GPUs 1.

Higher GPU utilization 1.

Higher MFU

In summary, combining padding removals with token-count-based batching improves throughput and reduces latency, while improving resource utilization and lowering operational costs during short query embedding inference.

Next Steps

To learn more about how Voyage AI’s state-of-the-art embedding models and rerankers can help you build accurate, reliable semantic search and AI applications, see the Voyage AI by MongoDB page.

Many thanks to Tengyu Ma, Andrew Whitaker, Ken Hong, Angel Lim, and Andrew Gaut for many helpful discussions along the way, and to Akshat Vig, Murat Demirbas, and Stan Halka for thoughtful reviews and feedback.