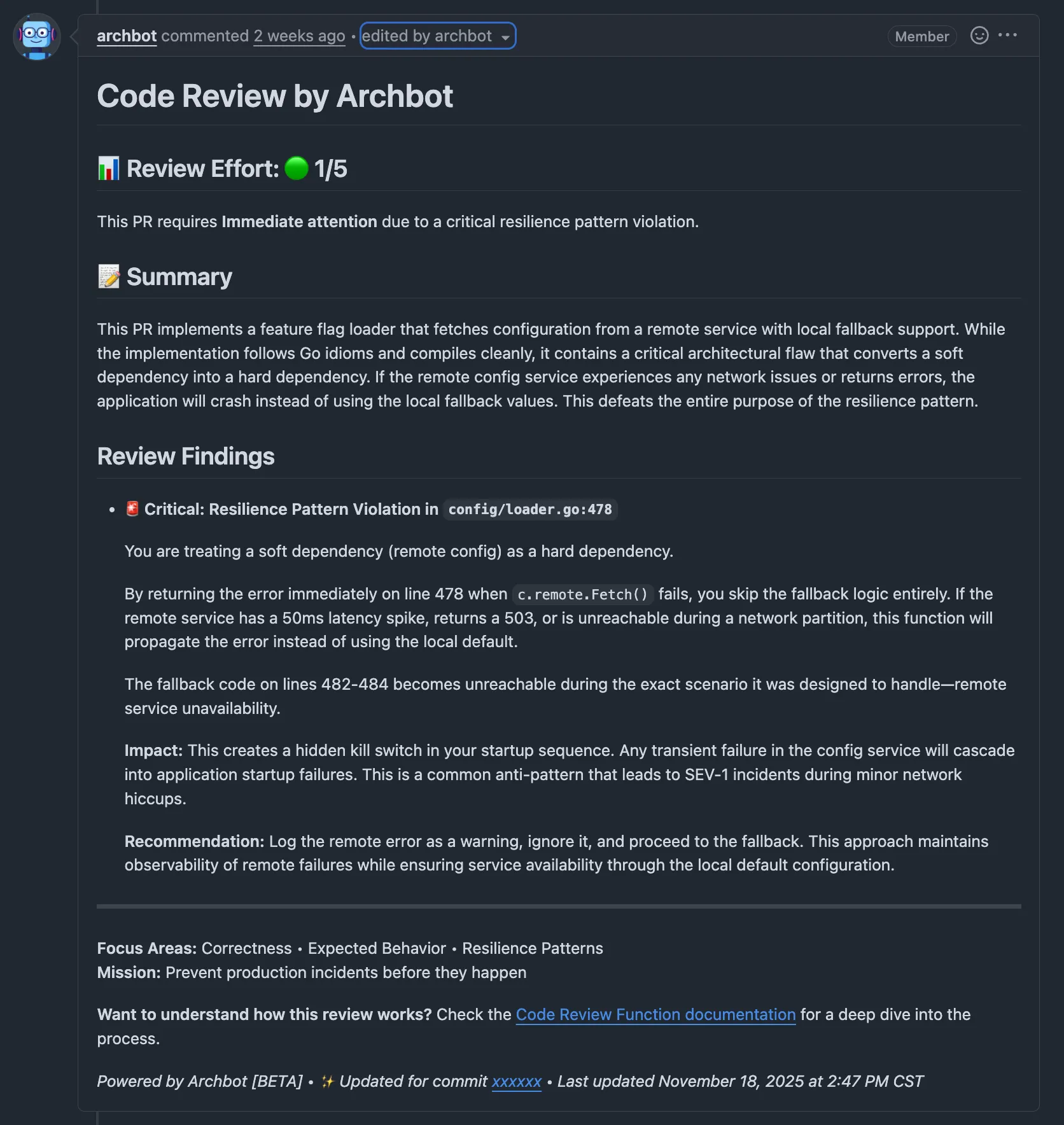

Two weeks after deploying our custom AI code reviewer, it caught a bug that would have crashed our payment processing. A senior engineer’s PR looked clean—it compiled, passed linting, followed Go idioms. But the AI spotted a subtle pattern: we’d accidentally turned a soft dependency into a hard one. If our config service blinked, our main service would die.

The engineer’s response? “Oh.”

That’s when the team stopped treating Archbot like a toy.

Here’s the problem we were solving: we run GitHub Enterprise behind a VPN. Modern AI code review tools like Cursor, Github Copilot, and CodeRabbit expect cloud-hosted repos. We couldn’t pipe proprietary code into the…

Two weeks after deploying our custom AI code reviewer, it caught a bug that would have crashed our payment processing. A senior engineer’s PR looked clean—it compiled, passed linting, followed Go idioms. But the AI spotted a subtle pattern: we’d accidentally turned a soft dependency into a hard one. If our config service blinked, our main service would die.

The engineer’s response? “Oh.”

That’s when the team stopped treating Archbot like a toy.

Here’s the problem we were solving: we run GitHub Enterprise behind a VPN. Modern AI code review tools like Cursor, Github Copilot, and CodeRabbit expect cloud-hosted repos. We couldn’t pipe proprietary code into them. But we still wanted AI code review on every PR.

So I built it myself.

This is the story of Archbot, the custom AI code reviewer I built to run securely inside enterprise networks. It started as a weekend hack (“how hard could it be?”). Spoiler alert: it didn’t start well.

What I learned (and want to teach you):

- Why naive git diff + LLM approaches fail

- How to manage context windows for large repos

- Using Bedrock Tool schemas for structured LLM output

- Two-phase AI architecture for intelligent filtering

- Production patterns for running AI tools in CI/CD

Why Git Diff Alone Fails for AI Code Review

My first iteration was painfully simple. I wrote a Go program that fetched the git diff of a PR and sent it to the LLM with a prompt like: “Find bugs in this code.”

I felt like a genius for about five minutes. Then the results came in.

The AI would confidently claim:

Variable

userRepositoryis undefined.

I’d look at the code. It was imported right there at the top of the file. But because the git diff only shows changed lines (and a few lines of context), the AI couldn’t see the imports.

It was the equivalent of trying to review a book by reading only the sentences that were edited in the second draft. You lose the plot immediately.

Lesson learned: Context is king. Without the file definitions, imports, and surrounding scope, the AI is just guessing.

So I went back to the drawing board.

GitHub API Rate Limits and the Sequential Fetch Problem

My next attempt was obvious: don’t just send the diff—fetch the full files from GitHub’s API.

I updated the bot to parse the diff, identify which files were changed, and then use the GitHub API to fetch the full content of those files.

This worked… until someone opened a PR that touched 40 files.

My bot fired off 40 sequential API calls to GitHub. GitHub fired back a 429 Too Many Requests. The bot crashed. The developer waited 5 minutes for a review that never came.

And even when it did work, it was slow. We were burning network time just shuttling strings around. I realized I was trying to rebuild git clone over HTTP, poorly.

Using Repomix to Pack Repository Context for AI

I needed a way to pack the repository context efficiently. That’s when I found Repomix (formerly repopack).

Repomix solves a subtle problem: AI models don’t understand file systems. You can’t just tar a repo and send it—you need structure. Repomix walks your tree and outputs either XML or Markdown with clear file boundaries, respecting .gitignore, and including metadata like file sizes and token counts. It’s like pandoc for codebases.

Perfect, right?

There was just one catch: Repomix is a Node.js tool. Archbot is written in Go.

Why didn’t I just write the bot in Python/TypeScript? Two reasons: Concurrency and Deployment. We needed to handle bursts of webhook events without spinning up heavy worker processes, and shipping a single static binary to our distroless containers keeps our security team happy.

I didn’t want to rewrite my entire bot in TypeScript. I didn’t want to manage two separate deployment pipelines. And I definitely didn’t want to write a Go port of Repomix (that’s a two-month side quest).

So I did what platform engineers do best: I made the tools work together.

The Multi-Stage Build Solution

The solution was a standard Docker multi-stage build: compile the Go binary in one stage, run it in a Node runtime in the second.

# Stage 1: Build the Go binary

FROM golang:latest AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

RUN go mod download

RUN CGO_ENABLED=0 GOOS=linux go build -a -o /app/archbot ./cmd/.

# Stage 2: Runtime with Node for Repomix

FROM node:lts-bullseye

RUN apt-get update && \

apt-get install -y ca-certificates tzdata git && \

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

RUN npm install -g repomix

# Copy the pre-built Go binary from stage 1

COPY --from=builder /app/archbot /app/

EXPOSE 9000

CMD ["/app/archbot"]

We simply copy the compiled Go binary into a Node.js base image. The Go binary runs as the main process and uses exec.Command to shell out to the globally-installed repomix command when needed.

It’s not the purest architectural pattern, but it shipped the feature in 2 hours instead of 2 weeks. Sometimes, platform engineering is about making the tools work for you, not being a purist.

The Performance Win

Here’s what this actually improved: we stopped hammering the GitHub API.

When a PR comes in, Archbot clones the repo once (network call), runs repomix locally (disk I/O), and gets a nice XML string of the codebase in ~2 seconds. Compare that to the “Attempt 2” approach where we made 40+ sequential API calls per PR.

Git cloning is fast. S3 caching (we cache the repomix output) handles way more load than the on-prem GitHub API could. The bottleneck shifted from network to disk, which is exactly what you want.

Context Window Management for Large Repositories

We deployed the Repomix version. It worked great for small microservices.

Then we tried it on The Monolith™.

You know the one. Millions of lines of code. Hundreds of directories. When Repomix packed that repo, the resulting text file was massive—way larger than the context window of even the generous 200k token models.

And even if it did fit, sending 150k tokens for every simple bug fix is a great way to burn through your budget.

I realized I couldn’t just “feed the repo” to the AI. I had to replicate how I review code.

When I review a PR, I don’t read the entire codebase.

- I look at the diff.

- I check the file tree to see where the changes live.

- I open only the files that are relevant to the change to verify imports and usage.

We needed a Two-Phase Architecture.

Instead of blindly packing the entire repo, we split the review into two phases:

graph TB

User([Developer]) -->|Opens/Updates PR| Webhook[GitHub Webhook]

Webhook -->|Triggers| Archbot[Archbot Handler]

subgraph Phase1["Phase 1: Discovery (~500 tokens)"]

direction TB

Diff[Git Diff]

Tree[Directory Structure]

P1_LLM[Bedrock LLM]

FileList[Selected Files JSON]

Archbot --> Diff

Archbot --> Tree

Diff --> P1_LLM

Tree --> P1_LLM

P1_LLM -->|Tool: select_files| FileList

end

subgraph Packing["Context Packing (Local)"]

direction TB

RepomixTool[Repomix]

FocusedCtx[Focused Context~5k tokens]

FileList --> RepomixTool

RepomixTool --> FocusedCtx

end

subgraph Phase2["Phase 2: Deep Review (~5k tokens)"]

direction TB

P2_LLM[Bedrock LLM]

Comments[Review Comments JSON]

FocusedCtx --> P2_LLM

Diff -.-> P2_LLM

P2_LLM -->|Tool: perform_code_review| Comments

end

Comments --> GH_API[GitHub API]

GH_API -->|Posts Comments| PR[Pull Request]

Phase 1: Intelligent File Selection

Instead of sending the code immediately, we first send the AI the Directory Structure and the Diff.

We ask it a simple question: “Given these changes, which files do you need to read to verify correctness?”

The system prompt for this phase is carefully engineered to guide the AI’s selection:

You are a senior code reviewer. You must use the select_files tool to identify

which files are needed to verify the correctness of these changes. Consider:

imports, interface definitions, test coverage, and related business logic.

Be selective—choose only files directly relevant to understanding the change.

If a PR modifies a handler, you likely need the service it calls and any

interfaces it implements. You don't need unrelated files in the same directory.

The AI is surprisingly good at this. It will say:

“I see you modified

user_handler.go. I need to seeuser_service.goto check the interface anduser_handler_test.goto verify coverage.”

Forcing Structured Responses with Bedrock Tools

Cool, but how do we actually tell Bedrock what format to return?

This is where AWS Bedrock Tools become critical. Instead of hoping the LLM returns parseable text, you define a JSON schema that forces the model to return structured data in exactly the format you specify.

The model guarantees it returns valid JSON matching that schema. No regex parsing. No “I hope the AI formatted this correctly.” Just typed data you can unmarshal directly into a Go struct.

We use this pattern for both phases: Phase 1 uses a select_files tool schema (returns an array of file paths), and Phase 2 uses a perform_code_review tool schema (returns structured review comments with severity levels and inline suggestions). The AI can’t return freeform markdown even if it wants to. The schema is the contract.

We’ll see the actual code for these schemas in the implementation section below.

Phase 2: The Focused Review

Now that we have the list of 5-10 relevant files, we use Repomix to pack them into a focused context. But here’s the thing—even those selected files come with baggage.

Generated code. Vendored dependencies. Lock files. Binary artifacts. Test fixtures.

This is where Repomix’s exclusion list feature becomes critical. Instead of naively packing everything, Repomix lets you define exclusion patterns that filter out files that don’t make sense for AI review. Think .gitignore, but specifically tuned for context packing.

We configure Repomix to exclude:

- Generated proto files and mocks

- Third-party vendored code

- Large JSON fixtures and test data

- Binary assets and compiled artifacts

- Package lock files (sorry

package-lock.json, you’re 50k lines of noise)

The result? I take the selected files and pack them cleanly—stripping out the noise that would confuse the AI or burn tokens unnecessarily.

This reduces the context size from ~100k tokens (full repo) to ~5k tokens (filtered, focused context). It’s faster, cheaper, and because the noise is removed, the AI hallucinates less.

Let’s talk money. The naive approach of sending 150k input tokens plus ~5k output tokens to Claude Haiku 4.5 via Bedrock would cost roughly $0.18-0.20 per review (based on direct API pricing of $1/$5 per million input/output tokens—Bedrock pricing may vary). With the two-phase approach and Repomix’s exclusion filtering, I’m averaging 8k input tokens and ~2.5k output tokens per review—about $0.02 per review. At 50 PRs/day, that’s the difference between $300/month (naive) vs $30/month (optimized). The two-phase architecture pays for itself immediately.

Implementation: Bedrock Tools and Structured LLM Output

Okay, enough story time. Let’s look at the code.

The secret sauce isn’t just the prompting—it’s forcing the LLM to return structured data. Instead of parsing freeform markdown (nightmare fuel), we use AWS Bedrock’s “Tool” feature—essentially a JSON schema that constrains the model’s output. You define the shape you want, and the model guarantees it returns valid JSON matching that schema. No regex. No “I hope the AI formatted this correctly.” Just typed data.

One quick note: we’re using Bedrock’s Converse API, not the older InvokeModel approach that required raw JSON payload construction. The Converse API handles message formatting, tool schemas, and multi-turn conversations for you. If you’re still using InvokeModel, upgrade—it’ll save you hours of JSON wrangling.

Step 1: The Contract (Bedrock Tools)

First, we define the schema for our “tools”. In AWS Bedrock (or OpenAI), this tells the model exactly what JSON format we expect back.

Here is the select_files tool. Note how we explicitly ask for an array of file paths and a reasoning field.

// Imports:

// "github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/service/bedrockruntime/types"

// "github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/service/bedrockruntime/document"

// BuildSelectFilesTool creates a tool for selecting relevant files from a PR

func BuildSelectFilesTool() *bedrockTypes.ToolConfiguration {

schemaMap := map[string]interface{}{

"type": "object",

"properties": map[string]interface{}{

"files": map[string]interface{}{

"type": "array",

"items": map[string]interface{}{

"type": "string",

"description": "File path relative to repo root (e.g., 'src/main.go')",

},

"description": "List of relevant file paths to analyze.",

},

"reasoning": map[string]interface{}{

"type": "string",

"description": "Explanation of why these files were selected",

},

},

"required": []string{"files", "reasoning"},

}

// Wrap the schema in Bedrock's ToolConfiguration

toolSpec := &bedrockTypes.ToolMemberToolSpec{

Value: bedrockTypes.ToolSpecification{

Name: aws.String("select_files"),

Description: aws.String("Select the most relevant files for analysis based on the PR diff"),

InputSchema: &bedrockTypes.ToolInputSchemaMemberJson{

Value: document.NewLazyDocument(schemaMap),

},

},

}

return &bedrockTypes.ToolConfiguration{

Tools: []bedrockTypes.Tool{toolSpec},

ToolChoice: &bedrockTypes.ToolChoiceMemberTool{

Value: bedrockTypes.SpecificToolChoice{

Name: aws.String("select_files"),

},

},

}

}

This schema tells Bedrock: “You must return a JSON object with a files array of strings and a reasoning string. No other format is acceptable.”

When you pass this tool configuration to the Converse API, Bedrock guarantees it returns valid JSON matching that schema. The same pattern applies to Phase 2—we define a perform_code_review tool with fields for severity levels, inline comments, and code suggestions.

Step 2: Phase 1 - File Selection

When a PR comes in, we grab the diff and the file tree (Repomix gives us a nice “Directory Structure” summary we can reuse). We send that to the model.

Here’s the core logic from selectFilesForReview. This is production code with the defensive patterns you need when running this on every PR across 30 repositories.

func (r *CodeReviewAnalyzer) selectFilesForReview(ctx context.Context, prDiff string) ([]string, error) {

// Add timeout for production resilience

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 30*time.Second)

defer cancel()

// 1. Get directory structure from Repomix (cached)

repoStructure := r.ChangeContext.Repomix.DirectoryStructure

// 2. Build the prompt asking "Which files do you need?"

phase1Prompt := fmt.Sprintf(SelectFilesForReviewPrompt, repoStructure, prDiff)

// 3. Call Bedrock with the Tool Configuration

toolConfig := bedrock.BuildSelectFilesTool()

response, err := r.BedrockClient.Converse(ctx, SystemPrompt, phase1Prompt, toolConfig)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("bedrock converse failed: %w", err)

}

// 4. Extract structured tool response

toolJSON, err := bedrock.ExtractToolJSON(response)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to extract tool response: %w", err)

}

// 5. Unmarshal into typed struct

var selectResponse struct {

Files []string `json:"files"`

Reasoning string `json:"reasoning"`

}

if err := json.Unmarshal(toolJSON, &selectResponse); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("invalid json structure: %w", err)

}

// 6. Guard against runaway file selection

if len(selectResponse.Files) > 20 {

slog.Warn("AI selected too many files, truncating",

"requested", len(selectResponse.Files),

"limit", 20)

selectResponse.Files = selectResponse.Files[:20]

}

return selectResponse.Files, nil

}

Notice the defensive programming: timeouts with context.WithTimeout, explicit error wrapping with fmt.Errorf, structured logging with slog.Warn, and the guardrail cap that truncates oversized file selections. When you’re running this on every PR across 30 repositories, you need to assume the AI will occasionally hallucinate, the network will flake, or someone will open a 500-file refactor. The first week we deployed this, the AI tried to select 47 files for a 3-line CSS change. Without the cap, we would have blown our context window budget. Production systems need guardrails.

Step 3: Packing Context (The Repomix Magic)

Now that we have the selectedFiles list, we don’t need to re-clone anything. We have the Repomix data structure in memory (or cached). We just filter it to extract the context we need.

// BuildFileContext filters RepomixData to selected files and returns a packed string.

// Note: This example shows XML format for illustration. The production version outputs

// JSON using structured serialization for better type safety and easier parsing.

func (r *Runner) BuildFileContext(data *RepomixData, selectedFiles []string) (string, error) {

// 1. Create a lookup map for O(1) checks

keep := make(map[string]bool)

for _, f := range selectedFiles {

keep[f] = true

}

// 2. Filter the pre-packed files from Repomix

// We assume data.Files contains the parsed output from Repomix

var filteredFiles []repomix.File

for _, file := range data.Files {

if keep[file.Path] {

filteredFiles = append(filteredFiles, file)

}

}

if len(filteredFiles) == 0 {

return "", fmt.Errorf("no relevant files found in context")

}

// 3. Reconstruct the XML/Context string

// This replicates Repomix's output format but only for the subset

var sb strings.Builder

sb.WriteString("<repository>\n")

for _, f := range filteredFiles {

sb.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf("<file path=%q>\n%s\n</file>\n", f.Path, f.Content))

}

sb.WriteString("</repository>")

return sb.String(), nil

}

This transforms a 50MB repo into a precise 10KB context window containing only the files that matter.

Step 4: Phase 2 - The Review

Finally, I run the actual review. I feed it the focused context and ask for specific actionable feedback.

Crucially, we map the response to a Go struct that matches GitHub’s comment API structure. We also make sure to handle errors gracefully here too—no _ assigns allowed in production!

func (r *CodeReviewAnalyzer) performCodeReview(ctx context.Context, fileContext string, prDiff string) (*CodeReviewResult, error) {

// 1. Build the prompt with the focused context

phase2Prompt := fmt.Sprintf(ReviewPrompt, fileContext, prDiff)

// 2. Call Bedrock with the "perform_code_review" tool

toolConfig := bedrock.BuildCodeReviewTool()

response, err := r.BedrockClient.Converse(ctx, SystemPrompt, phase2Prompt, toolConfig)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// 3. Unmarshal the structured response

var reviewData struct {

Summary string `json:"summary"`

KeyConcerns []KeyConcern `json:"key_concerns"`

InlineComments []struct {

FilePath string `json:"file_path"`

Line interface{} `json:"line"`

Body string `json:"body"`

SuggestedCode string `json:"suggested_code"`

} `json:"inline_comments"`

}

toolJSON, err := bedrock.ExtractToolJSON(response)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to extract tool json: %w", err)

}

if err := json.Unmarshal(toolJSON, &reviewData); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to unmarshal review data: %w", err)

}

// Now we have structured data to send to GitHub API!

return processReviewData(reviewData), nil

}

The result? I get a list of InlineComments that I can loop over and POST directly to the GitHub Pull Request API. No regex parsing, no “I hope the AI formatted the markdown block correctly.” Just typed data.

Why Not Use an Existing Tool?

Fair question. Tools like CodeRabbit and Codeium Enterprise exist and they are fantastic. But here’s the deal: none of them worked with our specific constraints.

The primary driver was infrastructure. We run GitHub Enterprise on-premise behind a strict VPN. While many SaaS tools claim enterprise support, they typically expect your git instance to be reachable from the public internet (or require complex tunnel setups that our security team vetoed immediately). We simply couldn’t pipe our repositories into a cloud SaaS.

Once we accepted we had to build, we realized four massive benefits that validated the decision:

- Control: We could integrate deeply with our internal knowledge base. I’m talking about feeding the AI our specific architecture docs and Go style guides.

- Cost: SaaS tools usually charge per-seat ($20-50/user/month). I wanted per-PR pricing I could control. If we have a quiet month, I pay less.

- Data residency: This was non-negotiable. With a custom build using Bedrock in our VPC, zero code ever leaves our controlled environment.

- Customization: We have specific architectural rules (like “no direct DB calls in handlers”). Phase 2 adds these as custom fitness functions—something no off-the-shelf tool offered.

If you can use a SaaS tool, use it. This post is for when you can’t.

The First Save (And Why This Matters)

Catching syntax errors is cute. Catching logic bombs is why we built this.

Two weeks after deploying Archbot, it caught a bug that would have turned a minor network hiccup into a SEV-1 outage.

A Senior Engineer was implementing a “Feature Flag” loader. The pattern is common: fetch configuration from a remote service, but keep a local fallback for safety. The goal is resilience.

Here is a simplified version of the code:

func (c *ConfigLoader) GetFeatureFlag(ctx context.Context, flag string) (bool, error) {

// 1. Try to fetch from the remote config service

val, err := c.remote.Fetch(ctx, flag)

if err != nil {

// The "Safe" move? Fail fast.

return false, fmt.Errorf("remote config failed: %w", err)

}

// 2. If remote returns nothing (e.g. 404), fallback to local defaults

if val == nil {

return c.local.Get(flag), nil

}

return *val, nil

}

Do you see it? It looks clean. It compiles. It passes the linter. It follows the standard Go idiom: if err != nil { return err }.

But Archbot saw the architectural implication:

The engineer paused. “Oh.”

We had inadvertently built a “kill switch” into our startup sequence. If the config service blinked, our main application would crash. The fallback code—written specifically for that scenario—was unreachable code during an outage.

That’s when the team stopped treating Archbot like a toy.

The Real Impact: Shifting Code Review from “Find Problems” to “Verify Intent”

Now, don’t get me wrong—catching production bugs is the headline reason we built this. That’s what gets management buy-in. That’s what makes the case for the infrastructure investment.

But here’s what actually changed day-to-day: Archbot became the first filter on every PR, freeing human reviewers to focus on architecture instead of syntax.

Think about the traditional code review process. You open a PR. A senior engineer context-switches from their deep work, loads your branch, scans 15 files looking for imports, error handling, edge cases, architectural violations—all while trying to remember what you were trying to accomplish in the first place. It’s exhausting. By the time they get to the interesting architectural question (“Should this live in the service layer or the handler?”), their brain is already fried from scanning for nil checks.

Archbot inverts that. It handles the cognitive load of the “scan for obvious issues” phase. It’s not replacing human review—it’s augmenting it.

When Archbot leaves a comment, it’s doing one of two things:

- Spotlighting complexity: “Hey, this function has three nested error paths and I can’t tell if all branches are covered.” Even when Archbot is wrong, it’s usually highlighting code that deserves a second look.

- Catching the mundane: Missing error handling, unreachable fallback logic, off-by-one bugs in loops—the stuff that’s easy to miss when you’re mentally juggling architectural intent.

The result? Human reviewers spend less time hunting for bugs and more time asking the questions that matter: “Is this the right design? Does this scale? Is there a simpler way?”

And yes, Archbot nitpicks sometimes. It’ll flag a variable name it doesn’t like. It’ll suggest a refactor that doesn’t make sense in context. But the team learned quickly: if Archbot comments on it, it’s probably worth at least reading twice. Complex code attracts AI attention. That’s actually a feature, not a bug.

The shift we saw was subtle but real. Code review went from “find all the problems” to “verify the architectural intent.” Archbot doesn’t have architectural taste—but it frees up the humans who do to actually apply it.

The Result

The difference was night and day.

- Naive Approach: Hallucinations, missed context.

- Hammering: Slow, rate-limited.

- Monolith (Full Repo): Context overflow, expensive.

- Two-Phase Archbot: Fast, accurate, cheap.

What we’re seeing:

- Catching production-impacting logic bugs before merge

- Identifying missing test coverage in critical paths

- High acceptance rate for comments with minimal false positives

- Drastically lower API costs compared to per-seat SaaS pricing

- Zero data leaked outside our VPC

But catching bugs is only half the battle. The next evolution is Architecture Fitness Functions — teaching the AI to enforce our specific architectural rules (like “no direct DB calls in handlers” or “use circuit breakers for external APIs”). That’s a topic for another day.

Want to build something similar for your platform team? Let’s chat.