Depending on the nature of your application, you may be dealing with color spaces and color correction standards outside of sRGB. Whether it is an Adobe RGB image, Display P3 monitor, HDR10 color space, etc., you will need to know the correct ways to transfer between one color space to another, as well as being able to correctly apply and invert any encoding corrections so certain color mainpulations can work properly. Here, I have created a list of the different color correction methods, most common color formats, the method of converting between color spaces, and ways to clamp values of colors outside the destination color space.

COLOR FORMATS

There is more than one way to represent the same color. The different ways can be categorized as such:

- Three values representing…

Depending on the nature of your application, you may be dealing with color spaces and color correction standards outside of sRGB. Whether it is an Adobe RGB image, Display P3 monitor, HDR10 color space, etc., you will need to know the correct ways to transfer between one color space to another, as well as being able to correctly apply and invert any encoding corrections so certain color mainpulations can work properly. Here, I have created a list of the different color correction methods, most common color formats, the method of converting between color spaces, and ways to clamp values of colors outside the destination color space.

COLOR FORMATS

There is more than one way to represent the same color. The different ways can be categorized as such:

- Three values representing the insensities of the additive primary colors (RGB)

- One value representing hue, one value representing saturation, and one value quasi-representing luminance (HSV, HSL, HSY)

- One value presenting luminance, two values denoting chrominance (YUV, YCbCr)

- Three values representing the insensities of the subtractive primary colors, optionally one value for key (CMY, CMYK)

- Three values presenting the optical reception from different wavelengths (LMS)

- Device independent tri-stimulus values (XYZ), and the common transform for defining primaries in color spaces (xyY)

RGB

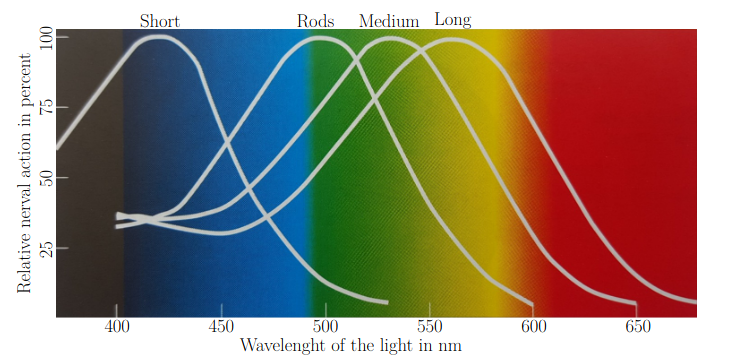

The most common way for images to be stored on the internet is with three channels of varying intensities of red, green, and blue; no intensity from each constitutes black, with full intensity from each constituting white. The reason it can work so well is because our eyes contains cones for detecting short (blue), medium (green), and long (red) wavelengths, and that certain monochromatic colors activate two or more of our cones at the same. For example, the color yellow activates both of our medium and long wavelength cones.

This means that if we shine both purely red and green light, it should create the same response inside your head as it would if we were to shine just the color yellow. And it does. This gives us a huge advantage where where just three primary colors (red, green, and blue), we can create a much wider range of colors than we previously thought. With 8-bit images whose range is from 0...255, we can create 16777216 (2^24) unique colors, and because of the facilitation brought by these phenomena mentioned, RGB became the most common standard for images and monitors. This does require the lights of each pixel to be small enough to create the illusion. But it is still there if you look really close and use a zoom feature of your camera.

![]()

YUV, YPbPr, AND YCbCr

Another way to format colors is YUV (or YCbCr if speaking digitally), where instead of storing the intensities of the three additive primary colors, you instead store the luminance (brightness effectively) of the color, and you write two color-difference chrominance values that dictate how blue-yellow (U or Cb) and how red-green (V or Cr) a color is. U and V being middle-valued will give a gray-scaled color.

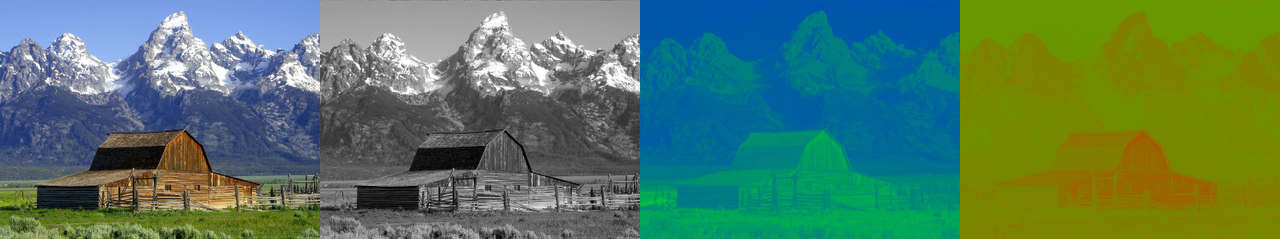

This was extremely useful in the days of when televisions just started to support colors. The original problem is to be able to send color signals in such a way without compromising the quality of black and white TVs. What was found is that because humans do not care out color nearly as much as contrast and luminance, they were able to squeeze color data by a large margin without affecting the quality of the image greatly. The artifacting resulted in tiny blips and dots throughout the monochrome television without otherwise affecting the quality of the image. This property got utilized in video formats where the same U and V value gets shared by a rectangular region of pixels. This concept in general is called chroma subsampling.

The picture above shows the list of different subsampling you may see in the wild, with the top three being the most common. Note that this showcases how each U and V pixel gets shared across the region of luminance pixels. The top three are often supported by graphics and hardware acceleration APIs, with the bottom three not so much. However, such subsamplings are rarely if ever present in the wild, but if you do run into one, you may need software support for these subsampling modes.

To convert from RGB to YUV for video compression and processing. You will need to utilize this matrix from below, taking encoded (not linear) RGB values as input.

Where refer to the luminance weights of the RGB color space in question. Whereas determines the maximum range for the U and V coordinates. All of these are defined by the respective color space and encoding standards.

For converting video frames into RGB images for processing, you may need the inverse of the matrix above, which can be easily computed as:

However, if you are to use YPbPr or its quantized version YCbCr for analog televsion or digital video processing processing, then you will need to set . Meaning we will have these matrices for YPbPr:

With YCbCr, instead of the range 0...1, you will deal with quantized values that are contained by the number of bits of your format, say from 0...255 for example.

Depending on whether you are using narrow or full range content, you will be dealing with different possible minimums and maximums for the luminance and chrominance values.

The most common for MPEG YUV content is limited range, which have the ranges (with n being the number of bits used to store color values):

For JPEG YUV content, you will see full range, which can be computed as (with n being the number of bits used to store color values):

Converting between analog YPbPr and digital YCbCr is a trivial linear relationship.

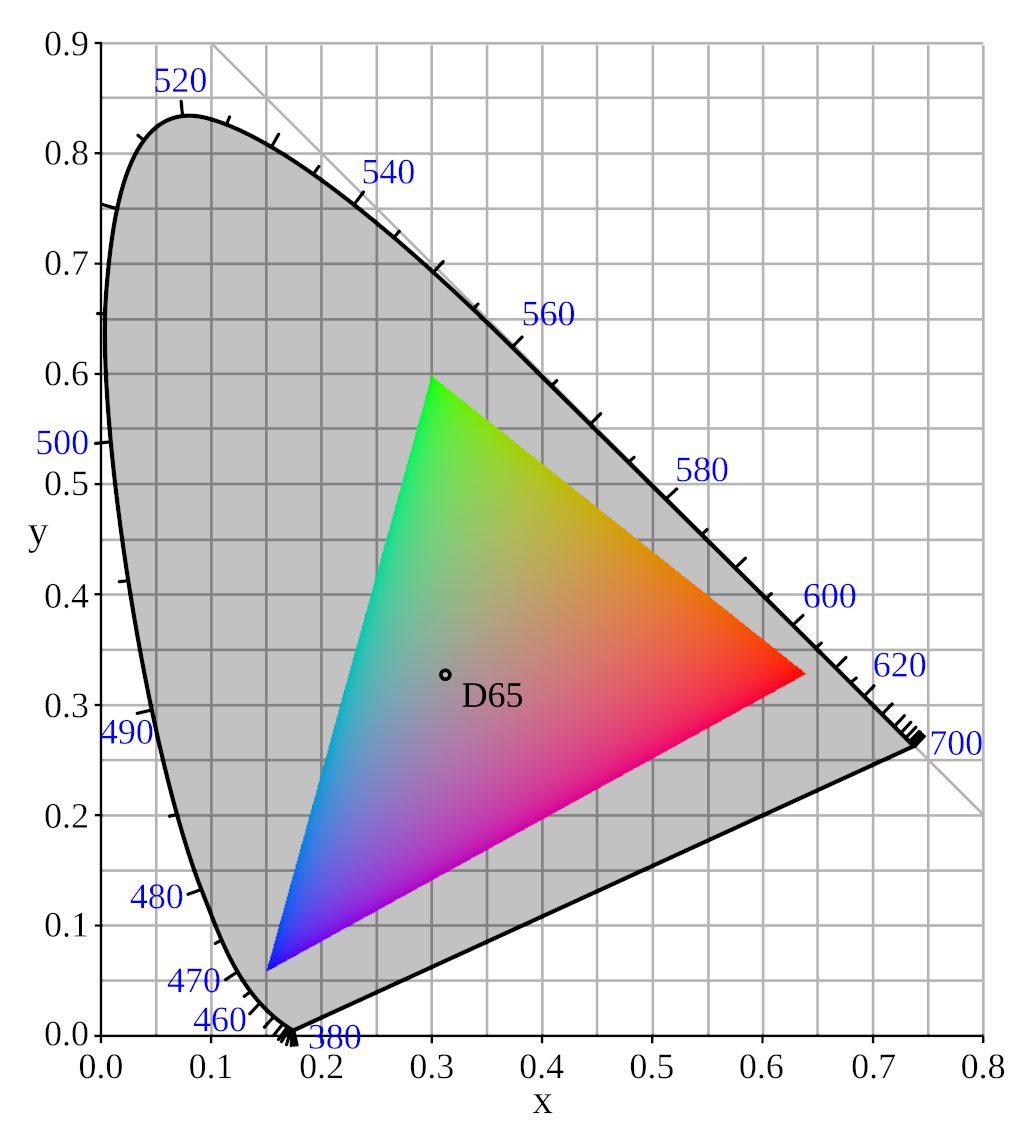

XYZ, xyY, AND COLOR GAMUTS

To be able to talk about color at a deeper level appropriately, we need to be able to have a useful diagram that shows the capabilities and limitations of human vision. The CIE 1931 Chromaticity Diagrams helps accomplish this by mapping out the range of possible colors of human vision into a 2D graph where the x and y are different chromaticity coordinates. The horse-shoe shape showcases the colors made from pure light wavelengths, from ~360 nm for violet all the way to ~830 nm for red. The line connecting the violets and the reds in the bottom create the purples which are not possible from any singular weavelength. Coordinates outside of this Spectral Locus are chromaticities that are not possible to be conceived by human vision.

Note: Most resources will only show wavelengths between 380 nm and 700 nm and other reduced ranges, but the 2 degree observer from the CIE’s 1931 diagram utilizes the larger range in a CSV.

When trying to define a color space for monitors and applications to use, you need to select a set of primary colors to denote the range of possible colors that can constructed, as well as a white point (ditto) for defining the brightest point in your color space. This can be done in terms of defining xy coordinates inside the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram.

Color Primaries

For sRGB, we use the same color space as the ITU-R BT.709 standard for HDTV. Thus the color space is defined under IEC 61966-2-1:1999 as:

| Chromaticity | Red | Green | Blue | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | 0.6400 | 0.3000 | 0.1500 | 0.3127 |

| y | 0.3300 | 0.6000 | 0.0600 | 0.3290 |

There is an entire list of these color primaries and the usage of each. 23 are defined, including reserved spaces in between.

| Value | Red x | Red y | Green x | Green y | Blue x | Blue y | White x | White y | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC |

| 1 | 0.640 | 0.330 | 0.300 | 0.600 | 0.150 | 0.060 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | Rec. ITU-R BT.709-6 Rec. ITU-R BT.1361-0 IEC 61966-2-1 sRGB or sYCC IEC 61966-2-4 SMPTE RP 177 (1993) |

| 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unspecified and ultimately determined by the application, usually chosen to be IEC 61966-2-1 sRGB or sYCC |

| 3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC |

| 4 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.71 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.310 | 0.316 | Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System M United States National Television System Committee (1953) United States Federal Communications Commission (2003) |

| 5 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System B, G Rec. ITU-R BT.601-7 625 Rec. ITU-R BT.1358-0 625 Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 625 PAL and 625 SECAM |

| 6 | 0.630 | 0.340 | 0.310 | 0.595 | 0.155 | 0.070 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | Rec. ITU-R BT.601-7 525 Rec. ITU-R BT.1358-1 525 or 625 Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 NTSC SMPTE ST 170 (2004) |

| 7 | 0.630 | 0.340 | 0.310 | 0.595 | 0.155 | 0.070 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | SMPTE ST 240 (1999) |

| 8 | 0.681 | 0.319 | 0.243 | 0.692 | 0.145 | 0.049 | 0.310 | 0.316 | Generic film (colour filters using Illuminant C) |

| 9 | 0.708 | 0.292 | 0.170 | 0.797 | 0.131 | 0.046 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | Rec. ITU-R BT.2020-2 Rec. ITU-R BT.2100-2 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/3 | 1/3 | SMPTE ST 428-1 (2019) (CIE 1931 XYZ as in ISO 11664-1) |

| 11 | 0.680 | 0.320 | 0.265 | 0.690 | 0.150 | 0.060 | 0.314 | 0.351 | SMPTE RP 431-2 (2011) |

| 12 | 0.680 | 0.320 | 0.265 | 0.690 | 0.150 | 0.060 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | SMPTE EG 432-1 (2010) |

| 13-21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC |

| 22 | 0.630 | 0.340 | 0.295 | 0.605 | 0.155 | 0.077 | 0.3127 | 0.3290 | The ITU-T has stated that "No corresponding industry specification identified". Then why? Why was it included to the list? And why 22? |

However, in order to have values that can be converted between color spaces, we need to know the luminances of each primary and ditto (white point) in question. This is because for converting xyY to XYZ, the luminance is required:

But trying to solve three equations with four unknwowns may be impossible, and here, you cannot get a unique solution here. Here’s the trick: we can define the luminance of the ditto to be 1. Doing so, we get these three equations:

Three equations, and three unknowns. Perfect, solving for the luminance of the three additive color primaries gets us these equations to compute them:

And now, to convert from RGB values from one gamut to the device-independent XYZ color space, you just use this formula:

And to go from XYZ to RGB again of a certain gamut, compute the XYZ matrix for that convertor, and invert it. You should note you can chain the two formulas together to convert intensities from one gamut to another.

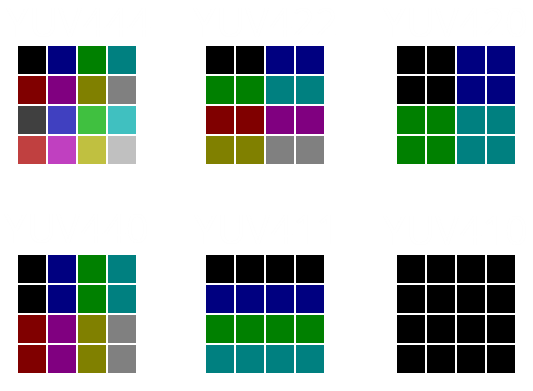

However, doing so risks colors from one gamut to not be found in another gamut, if the source space is larger than or just encompasses a different volume of color than the destination gamut. There are a few ways to cater to this gamut mismatch problem:

- You clamp the intensity values to be between 0 and 1

- You linearly compress the values to be a smooth gradient

- Convert the RGB to a different color space, perform 1. or 2., and convert it back to RGB

This is depending on what the artist or programmer values or intends, as each have their own advantages and disadvantages. Such as clipping of colors in the outer edge, or desaturation of the entire image.

COLOR TRANSFER FUNCTIONS

Our eyes do not perceive brightness in a simple, linear fashion. If you doubled the amount of light in a room, your eyes would not actually perceive that as twice as bright. Instead, you’d experience a logarithmic change. This non-linear perception is tied to how our vision works biologically. We’re much more sensitive to darker areas than to bright ones, and that is why the contrast between them feels so important in an image.

This human ability to contrast different shades of dark and inability to constrast shades of light nearly as well now brings an avantage to this phenomena: reducing space that a color can take up on disk. When compressing and trasmitting video, you want to ensure that the most important visual information is preserved. And because human eyes do not see light levels linearly, the way the video signal is encoded needs to both reduce chromatic distance for disk stroage, but maintain image quality.

Thus, functions to transform scenic light into video signal (opto-electronic transfer function) and to transform video signals to linear light for monitors (electro-optical transfer function) were born

The International Telecommunication Union has released recommendation H.273 in their Telecommunication Standardization Sector, listing out 19 Transfer Characteristics for such light transformations. These are either OETFs or inverse EOTFs, bear in mind.

Reference implementations of these transfer characteristics are provided below in GLSL.

const vec3 a_709 = vec3(1.09929682680944294035);

const vec3 b_709 = vec3(0.01805396851080780734);

const vec3 g_709 = vec3(0.00451349212772021864);

const vec3 a_240 = vec3(1.11157219592173121967);

const vec3 b_240 = vec3(0.02282158552944502221);

const vec3 a_rgb = vec3(1.05501071894758659721);

const vec3 b_rgb = vec3(0.00304128256012752085);

const vec3 a_b67 = vec3(0.17883277265694976563);

const vec3 b_b67 = vec3(0.28466890937220093749);

const vec3 c_b67 = vec3(0.55991072776271642980);

vec3 ITU_H273_transfer(vec3 L, int characteristic) {

switch(characteristic) {

case 0: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return L;

case 1: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.709-6 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1361-0 conventional colour gamut system */

return mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709));

case 2: /* Unspecified and ultimately determined by the application, normally either linear or sRGB */

return L;

case 3: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return L;

case 4: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System M | United States National Television System Committee 1953 | United States Federal Communications Commission (2003) | Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 625 PAL and 625 SECAM */

return pow(L, vec3(1.0/2.2));

case 5: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System B, G */

return pow(L, vec3(1.0/2.8));

case 6: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.601-7 525 or 625 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1358-1 525 or 625 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 NTSC | SMPTE ST 170 (2004) */

return mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709));

case 7: /* SMPTE ST 240 (1999) */

return mix(L * vec3(4.0), a_240 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_240 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_240));

case 8: /* Linear, unmodified transformation */

return L;

case 9: /* 100:1 Logarithmic transfer characteristic */

return mix(vec3(0.0), vec3(1.0) + ((log(L) / log(10.0))) / 2.0, greaterThanEqual(L, vec3(0.01)));

case 10: /* 100*sqrt(10):1 Logarithmic transfer characteristic */

return mix(vec3(0.0), vec3(1.0) + ((log(L) / log(10.0))) / 2.5, greaterThanEqual(L, vec3(sqrt(10.0) * 0.001)));

case 11: /* IEC 61966-2-4 */

return mix(-a_709 * pow(-L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709)), greaterThan(L, -b_709));

case 12: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.1361-0 extended colour gamut system */

return mix(-a_709 * pow(-4.0*L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709)), greaterThan(L, -g_709));

case 13: /* IEC 61966-2-1 sRGB | IEC 61966-2-1 sYCC */

return mix(-a_rgb * pow(-L, vec3(1.0/2.4)) - (a_rgb - vec3(1.0)), mix(L * vec3(12.92), a_rgb * pow(L, vec3(1.0/2.4)) - (a_rgb - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_rgb)), greaterThan(L, -b_rgb));

case 14: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.2020-2 (10-bit system) */

return mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709));

case 15: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.2020-2 (12-bit system) */

return mix(L * vec3(4.5), a_709 * pow(L, vec3(0.45)) - (a_709 - vec3(1.0)), greaterThanEqual(L, b_709));

case 16: /* SMPTE ST 2084 (2014) for 10-, 12-, 14- and 16-bit systems | Rec. ITU-R BT.2100-2 PQ system */

vec3 Lp = pow(L, vec3(1305.0/8192.0));

return pow((107.0/128.0 + 2413.0/128.0*Lp) / (1.0F + 2392.0/128.0*Lp), vec3(2523.0/32.0));

case 17: /* SMPTE ST 428-1 (2019) */

return pow(48.0/52.37 * L, vec3(1.0/2.6));

case 18: /* ARIB STD-B67 (2015) | Rec. ITU-R BT.2100-2 HLG system */

return mix(sqrt(3.0 * L), a_b67 * log(12.0 * L - b_b67) + c_b67, greaterThan(L, vec3(1.0/12.0)));

default: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return L;

}

}

vec3 ITU_H273_transferInverse(vec3 V, int characteristic) {

switch(characteristic) {

case 0: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return V;

case 1: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.709-6 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1361-0 conventional colour gamut system */

return mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709));

case 2: /* Unspecified and ultimately determined by the application, normally either linear or sRGB */

return V;

case 3: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return V;

case 4: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System M | United States National Television System Committee 1953 | United States Federal Communications Commission (2003) | Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 625 PAL and 625 SECAM */

return pow(V, vec3(2.2));

case 5: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.470-6 System B, G */

return pow(V, vec3(2.8));

case 6: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.601-7 525 or 625 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1358-1 525 or 625 | Rec. ITU-R BT.1700-0 NTSC | SMPTE ST 170 (2004) */

return mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709));

case 7: /* SMPTE ST 240 (1999) */

return mix(V / 4.0, pow((V + a_240 - vec3(1.0)) / a_240, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.0 * b_240));

case 8: /* Linear, unmodified transformation */

return V;

case 9: /* 100:1 Logarithmic transfer characteristic */

return mix(vec3(0.0), pow(vec3(100.0), V - 1.0), greaterThan(V, vec3(0.0)));

case 10: /* 100*sqrt(10):1 Logarithmic transfer characteristic */

return mix(vec3(0.0), pow(vec3(1000.0 / sqrt(10.0)), V - 1.0), greaterThan(V, vec3(0.0)));

case 11: /* IEC 61966-2-4 */

return mix(-pow((-V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709)), greaterThan(V, -4.5 * b_709));

case 12: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.1361-0 extended colour gamut system */

return mix(-0.25 * pow((-4.0 * V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709)), greaterThan(V, -4.5 * g_709));

case 13: /* IEC 61966-2-1 sRGB | IEC 61966-2-1 sYCC */

return mix(-pow((-V + a_rgb - vec3(1.0)) / a_rgb, vec3(2.4)), mix(V / 12.92, pow((V + a_rgb - vec3(1.0)) / a_rgb, vec3(2.4)), greaterThanEqual(V, 12.92 * b_rgb)), greaterThan(V, -12.92 * b_rgb));

case 14: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.2020-2 (10-bit system) */

return mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709));

case 15: /* Rec. ITU-R BT.2020-2 (12-bit system) */

return mix(V / 4.5, pow((V + a_709 - vec3(1.0)) / a_709, vec3(1.0 / 0.45)), greaterThanEqual(V, 4.5 * b_709));

case 16: /* SMPTE ST 2084 (2014) for 10-, 12-, 14- and 16-bit systems | Rec. ITU-R BT.2100-2 PQ system */

vec3 Vp = pow(V, vec3(32.0/2523.0));

return pow((Vp - vec3(107.0/128.0)) / (vec3(2413.0/128.0) - vec3(2392.0/128.0) * Vp), vec3(8192.0/1305.0));

case 17: /* SMPTE ST 428-1 (2019) */

return ((52.37/48.0) * pow(V, vec3(2.6)));

case 18: /* ARIB STD-B67 (2015) | Rec. ITU-R BT.2100-2 HLG system */

return mix(V*V / 3.0, (exp((V - c_b67) / a_b67) + b_b67) / 12.0 , greaterThan(V, vec3(0.5)));

default: /* For future use by ITU-T | ISO/IEC */

return V;

}

}

Reducing and optimizing these functions above are trivial and left as an exercise to the reader.

CONCLUSION

This page should be enough to give you the math and tools to convert between the different color spaces you may encounter, switch between gamuts, and being able to properly encode and decode image signals for proper color manipulation.

Citations

ITU-T H.273 : Coding-independent code points for video signal type identification Development of accessibility testing concepts for digital contents CIE 1931 colour-matching functions, 2 degree observer