GOTO 10

OpenAI built an AI coding agent and uses it to improve the agent itself

“The vast majority of Codex is built by Codex,” OpenAI told us about its new AI coding agent.

In interviews with Ars Technica this week, OpenAI employees revealed the extent to which the company now relies on its own AI coding agent, Codex, to build and improve the development tool. “I think the vast majority of Codex is built by Codex, so it’s almost entirely just being used to improve itself,” said Alexander Embiricos, product lead for Codex at OpenAI, in a conversation on Tuesday.

Codex, which OpenAI launched in its modern incarnation as a research…

GOTO 10

OpenAI built an AI coding agent and uses it to improve the agent itself

“The vast majority of Codex is built by Codex,” OpenAI told us about its new AI coding agent.

In interviews with Ars Technica this week, OpenAI employees revealed the extent to which the company now relies on its own AI coding agent, Codex, to build and improve the development tool. “I think the vast majority of Codex is built by Codex, so it’s almost entirely just being used to improve itself,” said Alexander Embiricos, product lead for Codex at OpenAI, in a conversation on Tuesday.

Codex, which OpenAI launched in its modern incarnation as a research preview in May 2025, operates as a cloud-based software engineering agent that can handle tasks like writing features, fixing bugs, and proposing pull requests. The tool runs in sandboxed environments linked to a user’s code repository and can execute multiple tasks in parallel. OpenAI offers Codex through ChatGPT’s web interface, a command-line interface (CLI), and IDE extensions for VS Code, Cursor, and Windsurf.

The “Codex” name itself dates back to a 2021 OpenAI model based on GPT-3 that powered GitHub Copilot’s tab completion feature. Embiricos said the name is rumored among staff to be short for “code execution.” OpenAI wanted to connect the new agent to that earlier moment, which was crafted in part by some who have left the company.

“For many people, that model powering GitHub Copilot was the first ‘wow’ moment for AI,” Embiricos said. “It showed people the potential of what it can mean when AI is able to understand your context and what you’re trying to do and accelerate you in doing that.”

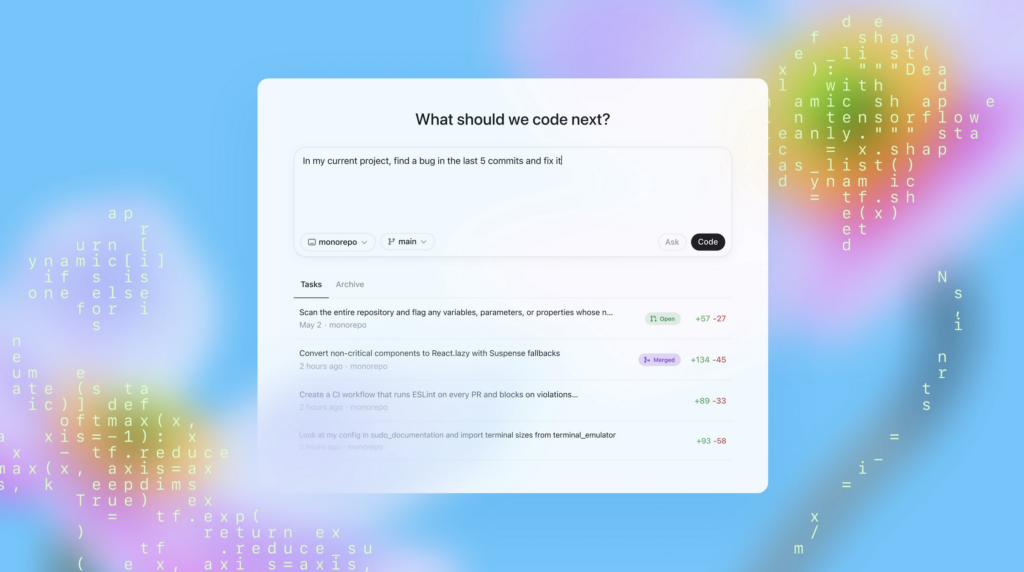

The interface for OpenAI’s Codex in ChatGPT. Credit: OpenAI

It’s no secret that the current command-line version of Codex bears some resemblance to Claude Code, Anthropic’s agentic coding tool that launched in February 2025. When asked whether Claude Code influenced Codex’s design, Embiricos parried the question but acknowledged the competitive dynamic. “It’s a fun market to work in because there’s lots of great ideas being thrown around,” he said. He noted that OpenAI had been building web-based Codex features internally before shipping the CLI version, which arrived after Anthropic’s tool.

OpenAI’s customers apparently love the command line version, though. Embiricos said Codex usage among external developers jumped 20 times after OpenAI shipped the interactive CLI extension alongside GPT-5 in August 2025. On September 15, OpenAI released GPT-5 Codex, a specialized version of GPT-5 optimized for agentic coding, which further accelerated adoption.

It hasn’t just been the outside world that has embraced the tool. Embiricos said the vast majority of OpenAI’s engineers now use Codex regularly. The company uses the same open-source version of the CLI that external developers can freely download, suggest additions to, and modify themselves. “I really love this about our team,” Embiricos said. “The version of Codex that we use is literally the open source repo. We don’t have a different repo that features go in.”

The recursive nature of Codex development extends beyond simple code generation. Embiricos described scenarios where Codex monitors its own training runs and processes user feedback to “decide” what to build next. “We have places where we’ll ask Codex to look at the feedback and then decide what to do,” he said. “Codex is writing a lot of the research harness for its own training runs, and we’re experimenting with having Codex monitoring its own training runs.” OpenAI employees can also submit a ticket to Codex through project management tools like Linear, assigning it tasks the same way they would assign work to a human colleague.

This kind of recursive loop, of using tools to build better tools, has deep roots in computing history. Engineers designed the first integrated circuits by hand on vellum and paper in the 1960s, then fabricated physical chips from those drawings. Those chips powered the computers that ran the first electronic design automation (EDA) software, which in turn enabled engineers to design circuits far too complex for any human to draft manually. Modern processors contain billions of transistors arranged in patterns that exist only because software made them possible. OpenAI’s use of Codex to build Codex seems to follow the same pattern: each generation of the tool creates capabilities that feed into the next.

But describing what Codex actually does presents something of a linguistic challenge. At Ars Technica, we try to reduce anthropomorphism when discussing AI models as much as possible while also describing what these systems do using analogies that make sense to general readers. People can talk to Codex like a human, so it feels natural to use human terms to describe interacting with it, even though it is not a person and simulates human personality through statistical modeling.

The system runs many processes autonomously, addresses feedback, spins off and manages child processes, and produces code that ships in real products. OpenAI employees call it a “teammate” and assign it tasks through the same tools they use for human colleagues. Whether the tasks Codex handles constitute “decisions” or sophisticated conditional logic smuggled through a neural network depends on definitions that computer scientists and philosophers continue to debate. What we can say is that a semi-autonomous feedback loop exists: Codex produces code under human direction, that code becomes part of Codex, and the next version of Codex produces different code as a result.

Building faster with “AI teammates”

According to our interviews, the most dramatic example of Codex’s internal impact came from OpenAI’s development of the Sora Android app. According to Embiricos, the development tool allowed the company to create the app in record time.

“The Sora Android app was shipped by four engineers from scratch,” Embiricos told Ars. “It took 18 days to build, and then we shipped it to the app store in 28 days total,” he said. The engineers already had the iOS app and server-side components to work from, so they focused on building the Android client. They used Codex to help plan the architecture, generate sub-plans for different components, and implement those components.

Ed Bayes, a designer on the Codex team, described how the tool has changed his own workflow. Bayes said Codex now integrates with project management tools like Linear and communication platforms like Slack, allowing team members to assign coding tasks directly to the AI agent. “You can add Codex, and you can basically assign issues to Codex now,” Bayes told Ars. “Codex is literally a teammate in your workspace.”

This integration means that when someone posts feedback in a Slack channel, they can tag Codex and ask it to fix the issue. The agent will create a pull request, and team members can review and iterate on the changes through the same thread. “It’s basically approximating this kind of coworker and showing up wherever you work,” Bayes said.

For Bayes, who works on the visual design and interaction patterns for Codex’s interfaces, the tool has enabled him to contribute code directly rather than handing off specifications to engineers. “It kind of gives you more leverage. It enables you to work across the stack and basically be able to do more things,” he said. He noted that designers at OpenAI now prototype features by building them directly, using Codex to handle the implementation details.

The command line version of OpenAI codex running in a macOS terminal window. Credit: Benj Edwards

OpenAI’s approach treats Codex as what Bayes called “a junior developer” that the company hopes will graduate into a senior developer over time. “If you were onboarding a junior developer, how would you onboard them? You give them a Slack account, you give them a Linear account,” Bayes said. “It’s not just this tool that you go to in the terminal, but it’s something that comes to you as well and sits within your team.”

Given this teammate approach, will there be anything left for humans to do? When asked, Embiricos drew a distinction between “vibe coding,” where developers accept AI-generated code without close review, and what AI researcher Simon Willison calls “vibe engineering,” where humans stay in the loop. “We see a lot more vibe engineering in our code base,” he said. “You ask Codex to work on that, maybe you even ask for a plan first. Go back and forth, iterate on the plan, and then you’re in the loop with the model and carefully reviewing its code.”

He added that vibe coding still has its place for prototypes and throwaway tools. “I think vibe coding is great,” he said. “Now you have discretion as a human about how much attention you wanna pay to the code.”

Looking ahead

Over the past year, “monolithic” large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4.5 have apparently become something of a dead end in terms of frontier benchmarking progress as AI companies pivot to simulated reasoning models and also agentic systems built from multiple AI models running in parallel. We asked Embiricos whether agents like Codex represent the best path forward for squeezing utility out of existing LLM technology.

He dismissed concerns that AI capabilities have plateaued. “I think we’re very far from plateauing,” he said. “If you look at the velocity on the research team here, we’ve been shipping models almost every week or every other week.” He pointed to recent improvements where GPT-5-Codex reportedly completes tasks 30 percent faster than its predecessor at the same intelligence level. During testing, the company has seen the model work independently for 24 hours on complex tasks.

OpenAI faces competition from multiple directions in the AI coding market. Anthropic’s Claude Code and Google’s Gemini CLI offer similar terminal-based agentic coding experiences. This week, Mistral AI released Devstral 2 alongside a CLI tool called Mistral Vibe. Meanwhile, startups like Cursor have built dedicated IDEs around AI coding, reportedly reaching $300 million in annualized revenue.

Given the well-known issues with confabulation in AI models when people attempt to use them as factual resources, could it be that coding has become the killer app for LLMs? We wondered if OpenAI has noticed that coding seems to be a clear business use case for today’s AI models with less hazard than, say, using AI language models for writing or as emotional companions.

“We have absolutely noticed that coding is both a place where agents are gonna get good really fast and there’s a lot of economic value,” Embiricos said. “We feel like it’s very mission-aligned to focus on Codex. We get to provide a lot of value to developers. Also, developers build things for other people, so we’re kind of intrinsically scaling through them.”

But will tools like Codex threaten software developer jobs? Bayes acknowledged concerns but said Codex has not reduced headcount at OpenAI, and “there’s always a human in the loop because the human can actually read the code.” Similarly, the two men don’t project a future where Codex runs by itself without some form of human oversight. They feel the tool is an amplifier of human potential rather than a replacement for it.

The practical implications of agents like Codex extend beyond OpenAI’s walls. Embiricos said the company’s long-term vision involves making coding agents useful to people who have no programming experience. “All humanity is not gonna open an IDE or even know what a terminal is,” he said. “We’re building a coding agent right now that’s just for software engineers, but we think of the shape of what we’re building as really something that will be useful to be a more general agent.”

Benj Edwards is Ars Technica’s Senior AI Reporter and founder of the site’s dedicated AI beat in 2022. He’s also a tech historian with almost two decades of experience. In his free time, he writes and records music, collects vintage computers, and enjoys nature. He lives in Raleigh, NC.