Apache Iceberg has become a serious default in modern data architecture conversations. The reason isn’t hype. Iceberg makes tables feel like an abstraction you can commit to, while keeping compute flexible across engines and over time. As more teams aim for “open foundation + multiple engines,” Iceberg stops being an experiment and starts being infrastructure.

As that adoption moves from experimentation to day-to-day use, the questions change. Early on, teams ask about formats, catalogs, and engine support. Later, they ask what it takes to keep Iceberg reliable without accumulating fragility, glue, and a growing platform tax. In our customer conversations, the bottleneck is rarely choosing Iceberg. The bottleneck is the surrounding pipeline system that makes Iceberg predictable a…

Apache Iceberg has become a serious default in modern data architecture conversations. The reason isn’t hype. Iceberg makes tables feel like an abstraction you can commit to, while keeping compute flexible across engines and over time. As more teams aim for “open foundation + multiple engines,” Iceberg stops being an experiment and starts being infrastructure.

As that adoption moves from experimentation to day-to-day use, the questions change. Early on, teams ask about formats, catalogs, and engine support. Later, they ask what it takes to keep Iceberg reliable without accumulating fragility, glue, and a growing platform tax. In our customer conversations, the bottleneck is rarely choosing Iceberg. The bottleneck is the surrounding pipeline system that makes Iceberg predictable at scale.

Iceberg defines tables, not pipelines

Iceberg defines table behavior and evolution, but it doesn’t take responsibility for operating pipelines around those tables. In a real deployment, tables still need continuous ingestion from operational systems, transformations that stay synchronized with upstream change, and ongoing table operations that keep performance and cost under control. You can assemble this from separate tools, but reliability ends up living in the seams between systems rather than in a single place you can reason about.

A concrete version of this shows up in almost every “patchwork” stack. A schema change lands upstream. Ingestion starts writing new fields into Iceberg. dbt Core runs later on a schedule and either fails, or worse, “succeeds” while producing partial results because assumptions no longer match reality. Meanwhile, table maintenance runs independently, compacting files and expiring snapshots on its own cadence. When something looks wrong downstream, you end up debugging across four places: the ingestion tool, the transformation job, the scheduler, and the table ops scripts. None of those systems is “broken” in isolation, but the combined behavior is brittle because no one system is responsible for the loop as a whole.

Iceberg also makes the operational nature of this hard to ignore. Snapshots accumulate, metadata grows, and cleanup has to happen continuously if you want predictable performance and manageable costs. Multiply that across hundreds of tables, and “operating Iceberg” becomes a first-class responsibility rather than something you bolt on after the fact.

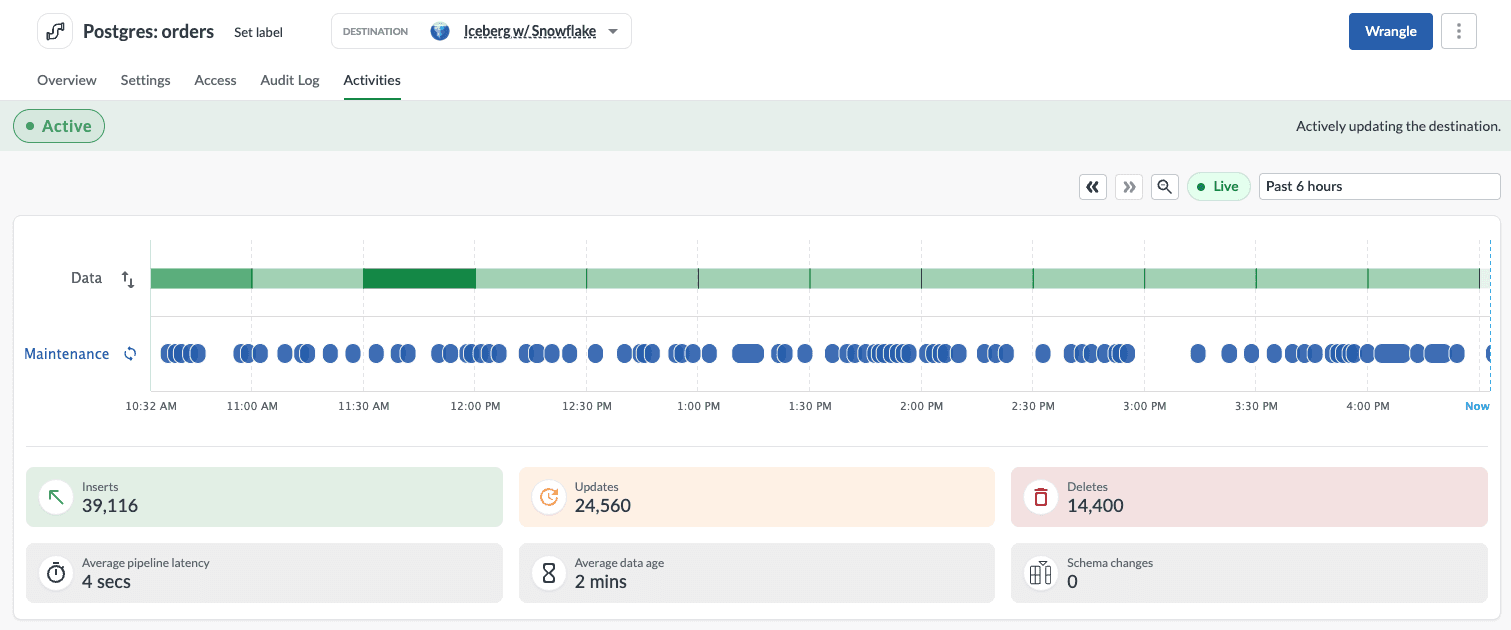

An Iceberg pipeline in Etleap: continuous ingestion into Iceberg with automated maintenance running alongside it, with freshness and change volume visible in real time.

What we mean by a pipeline layer around Iceberg

When we talk about a “pipeline layer around Iceberg,” we mean a system that takes responsibility for the operational loop end to end. It isn’t just an orchestrator, and it isn’t just an ingestion tool. It’s the layer that continuously moves data into Iceberg, runs transformations (including dbt Core) in sync with upstream change, and keeps tables healthy through ongoing operations.

The unit of reasoning isn’t “a job ran at 2am.” It’s “this table, its state, and what downstream depends on,” because that’s what breaks when the pipeline is split across tools that coordinate by convention. In practice, teams end up assembling a patchwork of ingestion tools, dbt Core jobs, orchestrators, and custom Iceberg maintenance, and that patchwork becomes expensive to build, hard to operate, and fragile as the system evolves.

Table state beats schedules

Most stacks coordinate ingestion, dbt Core runs, and table operations using schedules. That can work, but it hard-codes a fragile assumption: time is the coordination primitive. In a stateful table world, the durable primitive is table state: what changed, what snapshot is current, which models are now stale, and what operations should run to keep tables healthy.

Schedules are only a proxy for those facts. They behave fine when everything is batch and stable. They behave poorly once ingestion is continuous, schema changes are normal, and table operations meaningfully affect performance. At that point, “run dbt Core every hour” stops being an architecture and starts being a guess.

A table-state-first system answers “what should run next” from the actual state of the tables. Ingestion produced a new snapshot. That snapshot invalidates specific downstream models. Certain tables now meet the criteria for compaction or snapshot expiry. Downstream consumers can read a consistent version once the right steps complete. The scheduler becomes an implementation detail instead of the thing holding the system together, and the whole system becomes easier to reason about as it grows.

Why this is the next step for Etleap

This is why evolving Etleap toward Iceberg felt like an architectural necessity rather than “we added a new destination.” Etleap started from a simple frustration: pipelines become engineering projects when operational responsibility is spread across too many disconnected parts. Over the years we built monitoring, reliability features, and end-to-end pipelines that include dbt Core in the same workflow as ingestion. Iceberg sharpened the same lesson: if your system isn’t designed around table state and continuous operations, teams end up rebuilding a bespoke platform around it.

A small but telling example is data quality expectations. In many stacks, dbt Core tests are downstream assertions: you discover violations only after a model runs, which means you burn compute and can propagate bad assumptions before you find the issue. In an integrated pipeline system, those expectations can become part of the pipeline contract. You can detect violations at the boundary where data lands and prevent downstream work from proceeding on a broken assumption. It’s not magic. It’s what becomes possible when one system owns the loop rather than several tools coordinating indirectly.

What we’re launching

This is the motivation for what we’re launching: the Iceberg pipeline platform. It’s a new kind of pipeline system designed specifically for Apache Iceberg, built to serve as the missing pipeline layer Iceberg itself lacks. It unifies ingestion, transformations, orchestration, and Iceberg table operations into a single managed system, so teams can use Iceberg as a foundation for analytics and AI without building and operating a custom pipeline stack. The platform runs entirely inside the customer’s VPC, so teams get a managed system without giving up cloud control.

IDC captured the broader trend well, and I agree with the framing because it acknowledges both the promise and the operational reality of enterprise adoption:

“There is a strong industry consensus around the potential of Apache Iceberg to improve performance and provide interoperability across diverse data sources,” said Marlanna Bozicevich, Senior Research Analyst at IDC. “In today’s data landscape, where organizations are under pressure to deliver faster insights from increasingly complex environments, solutions like Etleap’s that unify pipeline management and Iceberg operations can help teams meet performance and scalability demands while maintaining architectural openness.”

That phrase “maintaining architectural openness” matters. Iceberg is attractive because it lets teams avoid locking their data foundation to one engine. But adopting Iceberg without a coherent operating layer often leads teams to recreate a different kind of lock-in: the internal platform they had to build to make it all work. Our goal is to make Iceberg operationally straightforward enough that teams can keep the openness they wanted, without paying the platform tax that often follows.

Want to see it in action? Book a demo here.