**T****here is something quietly subversive about unfolding an idea step by step. ****Tony Breu helped shape tweetorials as a genre. I asked him what it is that still makes them special. **

It’s like birdsong fading at the end of summer. You didn’t really notice it disappear, but then it just has.

With the migration from X/Twitter to other platforms, fewer scientists seem to be posting tweetorials, and that is a pity. Tweetorials do actually work on platforms like Bluesky even if you call them something else. But fewer scientists seem to be daring to invest the time to write them. As newsfeeds on content-sharing platforms like LinkedIn are overrun by AI-generated slop, it might be time to revi…

With the migration from X/Twitter to other platforms, fewer scientists seem to be posting tweetorials, and that is a pity. Tweetorials do actually work on platforms like Bluesky even if you call them something else. But fewer scientists seem to be daring to invest the time to write them. As newsfeeds on content-sharing platforms like LinkedIn are overrun by AI-generated slop, it might be time to revi…

**T****here is something quietly subversive about unfolding an idea step by step. ****Tony Breu helped shape tweetorials as a genre. I asked him what it is that still makes them special. **

It’s like birdsong fading at the end of summer. You didn’t really notice it disappear, but then it just has.

With the migration from X/Twitter to other platforms, fewer scientists seem to be posting tweetorials, and that is a pity. Tweetorials do actually work on platforms like Bluesky even if you call them something else. But fewer scientists seem to be daring to invest the time to write them. As newsfeeds on content-sharing platforms like LinkedIn are overrun by AI-generated slop, it might be time to revisit the good old tweetorial.

With the migration from X/Twitter to other platforms, fewer scientists seem to be posting tweetorials, and that is a pity. Tweetorials do actually work on platforms like Bluesky even if you call them something else. But fewer scientists seem to be daring to invest the time to write them. As newsfeeds on content-sharing platforms like LinkedIn are overrun by AI-generated slop, it might be time to revisit the good old tweetorial.

So what are they, actually?

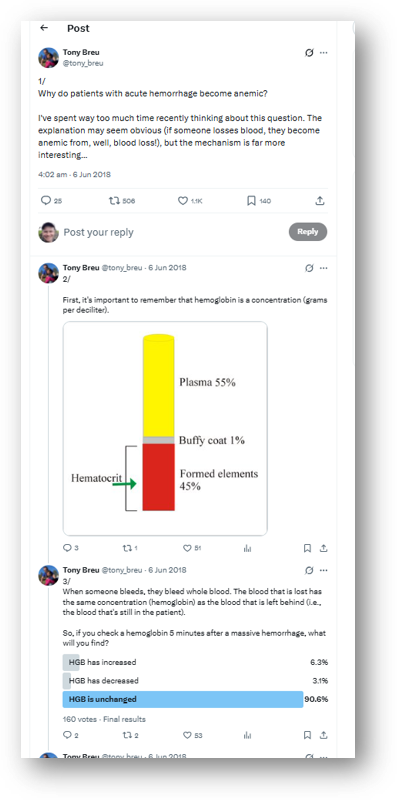

Tweetorials are a string of tightly written, connected tweets that question or explain something complex, with each of the tweets retweetable and potentially the start of a new sub-thread, drawing the curious reader downwards and setting off new scientific conversations. You can see an example of the start of one on the image to the right.

For a few years, tweetorials seemed to be everywhere.

On Twitter, they were ideal as introductions to a research topic, and scientists typically pinned tweetorials explaining their own research at the top of their profile, effectively making the perfect introduction to a first-time visitor to their profile.

As a genre they didn’t play well with the platforms that want you to share one-off pieces of ‘content‘ (like LinkedIn) that then algorithmically compete for readers’ attention. But this was a good thing. They were for works of art, made for long-term consumption. Refreshing.

If you’re able to engender an interest in just a few small parties who have more of a following than you, then it has the ability to explode

Tony Breu

They were invented by users: Microblogging platforms like the old Twitter had character limits to encourage brevity. Users then went beyond the imposed character limit by threading multiple tweets together as threads. Tweetorials, a sub-genre of these threads that acted as ‘tutorials’, were a genre of threads that was then invented by scientists.

Tweetorials are a perfect fit for science.

They can be structured like tight versions of academic papers, with a question, leading to a methods section, a discussion, and a conclusion. This meant that academics could easily reformulate already existing papers as tweetorials.

Also, because each of the underlying tweets can be discussed and commented, they often start new conversations, with an original tweetorial leading to several separate chains of comments and new ideas.

The format invokes scientific curiosity in the reader, teasing them with a short research question, and inviting them to follow along a thought process tweet by tweet.

Some researchers even post them as slow threads, one post at a time with a delay, allowing the reader to follow a researcher’s work in real time.

If anyone is at the centre of the tweetorial genre it is Tony Breu, Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School. He has written more than 130 of them.

If anyone is at the centre of the tweetorial genre it is Tony Breu, Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School. He has written more than 130 of them.

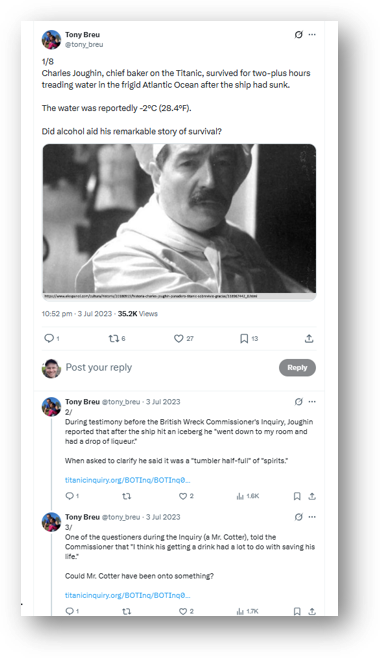

His tweetorials were consumed, argued and commented by doctors, nurses, pharmacists, students, and researchers from other fields. They have titles like ‘Charles Joughin, chief baker on the Titanic, who survived for two-plus hours treading water in the frigid Atlantic Ocean after the ship had sunk’ to ‘Have you ever wondered why we don’t use steroids to treat acute pancreatitis (AP)? I have!’

So when I started my book on Social Media For Research Impact with Marcel Bogers, I leapt at the opportunity to interview him.

Tony Breu posted his first tweetorial in 2018.

“So I had thought about this question in the shower the day before and it was really gnawing at me: Why does someone’s hematocrit, the concentration of red blood cells decrease, when they have an acute bleed? When you’re bleeding you bleed whole blood, so the concentration of hemoglobin shouldn’t change,” he recalls.

“I thought, let me sit down at my computer in front of the TV and throw together something with no expectation that anyone was going to be interested. At that point, I had a few hundred followers at most. But if you’re able to engender an interest in just a few small parties who have more of a following than you, then it has the ability to explode,” he says.

It did.

In fact, he told me, it turned out to be the most popular thing he’d ever done.

100s of tweetorials later, he has a mass following on X. His new account posting tweetorials on Bluesky already has a large following there also.

A tweetorial for him would take six to ten hours to make. To give you an idea of the process he has written a tweetorial (my favourites!) on how to write tweetorials here and here.

A tweetorial for him would take six to ten hours to make. To give you an idea of the process he has written a tweetorial (my favourites!) on how to write tweetorials here and here.

“I’ve never measured how long it took me to produce a tweetorial. But for a typical one that I’ve written over the last few years, I will download 50-100 academic articles, and read in detail at least 10 of those, So just the research component can take, let’s say, three to five hours. The actual construction of the tweetorial doesn’t take as much time in 2025, but certainly two to three hours,” he tells me.

This is a significant time investment. But they are widely reposted, commented and read. And in Tony Breu’s case, they have had a real impact in the world.

What a tweetorial wants to do is use a medium that is specifically geared towards quick consumption, like X or Bluesky, and do something with it that is the exact opposite, which is demand people’s attention for five to 10 minutes.

Tony Breu

In one tweetorial, for example, Tony asked why corticosteroids weren’t used in cases of pancreatitis. The thread caught the attention of a critical care doctor he had once worked with, who decided to launch a randomised trial to test the idea. The trial is still ongoing.

Some of Tony Breu’s tweetorials got hundreds of thousands of views, and his latest ones still get a lot of attention.

But tweetorials may be declining as a genre. And this is not solely a result of the decline of Twitter/X as a platform for scientific ideation. There is a paradox at the heart of the tweetorial, according to Tony Breu:

“By definition, what a tweetorial wants to do is use a medium that is specifically geared towards quick consumption, like X or Bluesky, and do something with it that is the exact opposite, which is demand people’s attention for five to 10 minutes.”

Trying to replicate what we do in tweetorials with TikTok, that is just not going to work. That’s impossible

Tony Breu

Tweetorials were, in effect, a way in which academics revolted against the constraints of the platform. This then turned out to be an enticing way of sometimes driving scientific curiosity towards scientific problems.

“I don’t anticipate a rejuvenation. I don’t think we’re going to get back to where we were,” says Tony Breu. “There’s probably going to be some other way that people do this work that isn’t the tweetorial. These model may work, continue to work in the future. But trying to replicate what we do in tweetorials with TikTok, that is just not going to work. That’s impossible.”

“I don’t anticipate a rejuvenation. I don’t think we’re going to get back to where we were,” says Tony Breu. “There’s probably going to be some other way that people do this work that isn’t the tweetorial. These model may work, continue to work in the future. But trying to replicate what we do in tweetorials with TikTok, that is just not going to work. That’s impossible.”

Generative AI can now produce a post, as ‘content’, faster, cleaner, and more impersonally than ever. This will speed up the actual posting process, even for something like a tweetorial. But this will prove to be the downfall of content-sharing platforms, if newsfeeds turn into a long queue of AI slop.

Tweetorial was, after all, never just ‘content’. It was a process and the reader could see it. You can automate a summary, but you can’t automate curiosity.

Tony Breu also has some of his recent tweetorials on Bluesky.

Tony Breu is currently taking a break from tweetorials. He is writing a book with Avraham Cooper called Why Doesn’t Your Stomach Digest Itself?

“It’s about human resilience and about how the body is able to withstand a constant barrage of things that are trying to put it awry, but also how in even extreme situations, humans are able to maintain themselves,” he explains.

Tony reckons still plans to write tweetorials once his book is finished. “If a hundred people read it instead of a hundred thousand, that’s fine,” he told me. He does it also for his own sake:

I’ve come to terms with the fact that when I put these together, the main learner is me

Tony Breu

“I hate to say it, but a typical tweetorial, if I were to take one of them three months later, and I had the option to interview all the people who had read it from the first tweet till the end, I bet you most of those people would not remember very much from it.“

“Even I, three months later, may only remember 80% of it! But that’s okay. I’ve come to terms with the fact that when I put these together, the main learner is me,” he says.

“Anyone else who learns is just gravy.”

You can see a full list of Tony Breu’s tweetorials here.

Tony Breu is also co-host with Avraham Cooper on the medical podcast The curious clinicians.

*Social media for research impact is a new book *by Mike Young and Marcel Bogers (forthcoming January 2026). It invites you to think more clearly — and ethically — about how to use social media. Not just to disseminate your research, but to connect, ideate, co-create, and stay open to the unexpected. The book page is here.