In 2020, while lots of people were baking bread, I was building LEGO sets.

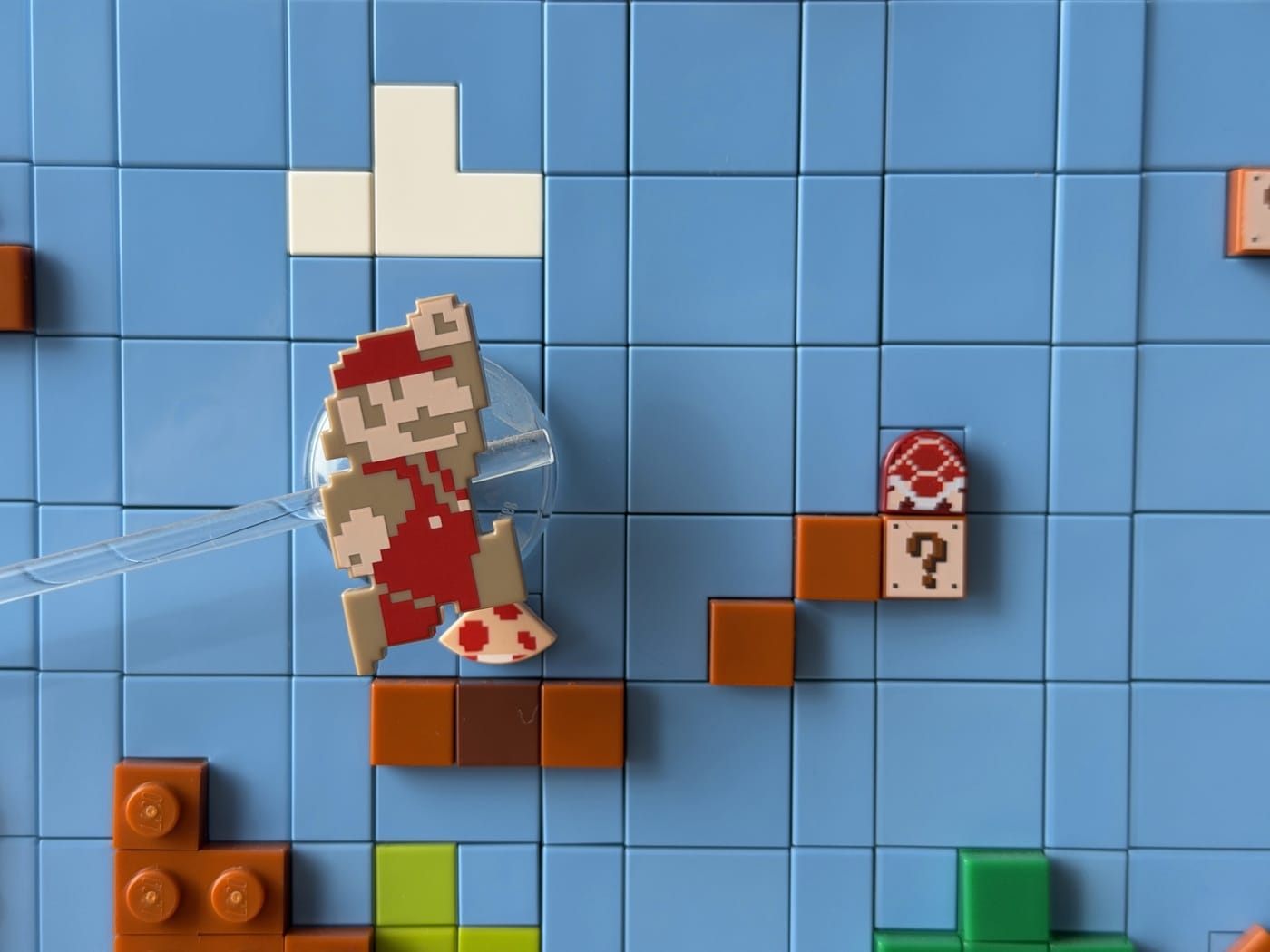

Through the following years, I picked up a number of interesting sets. There was the Nintendo Entertainment System. I rebuilt my old Voltron set. There was the Super Mario 64 Question Mark Block, and more—and, most recently, my sister’s and my favorite Transformer toy, now in LEGO form.

A lot of this was just joyfully being a kid at heart. But there was something else really interesting about them. They all had some kind of mechanical contr…

In 2020, while lots of people were baking bread, I was building LEGO sets.

Through the following years, I picked up a number of interesting sets. There was the Nintendo Entertainment System. I rebuilt my old Voltron set. There was the Super Mario 64 Question Mark Block, and more—and, most recently, my sister’s and my favorite Transformer toy, now in LEGO form.

A lot of this was just joyfully being a kid at heart. But there was something else really interesting about them. They all had some kind of mechanical contrivance to them. Something that made them do more than just sit on a shelf and look pretty.

Putting these together, carefully following the instructions—I found myself also reflecting on how building software and building expertise go hand-in-hand.

Building the mechanism—and the knowledge

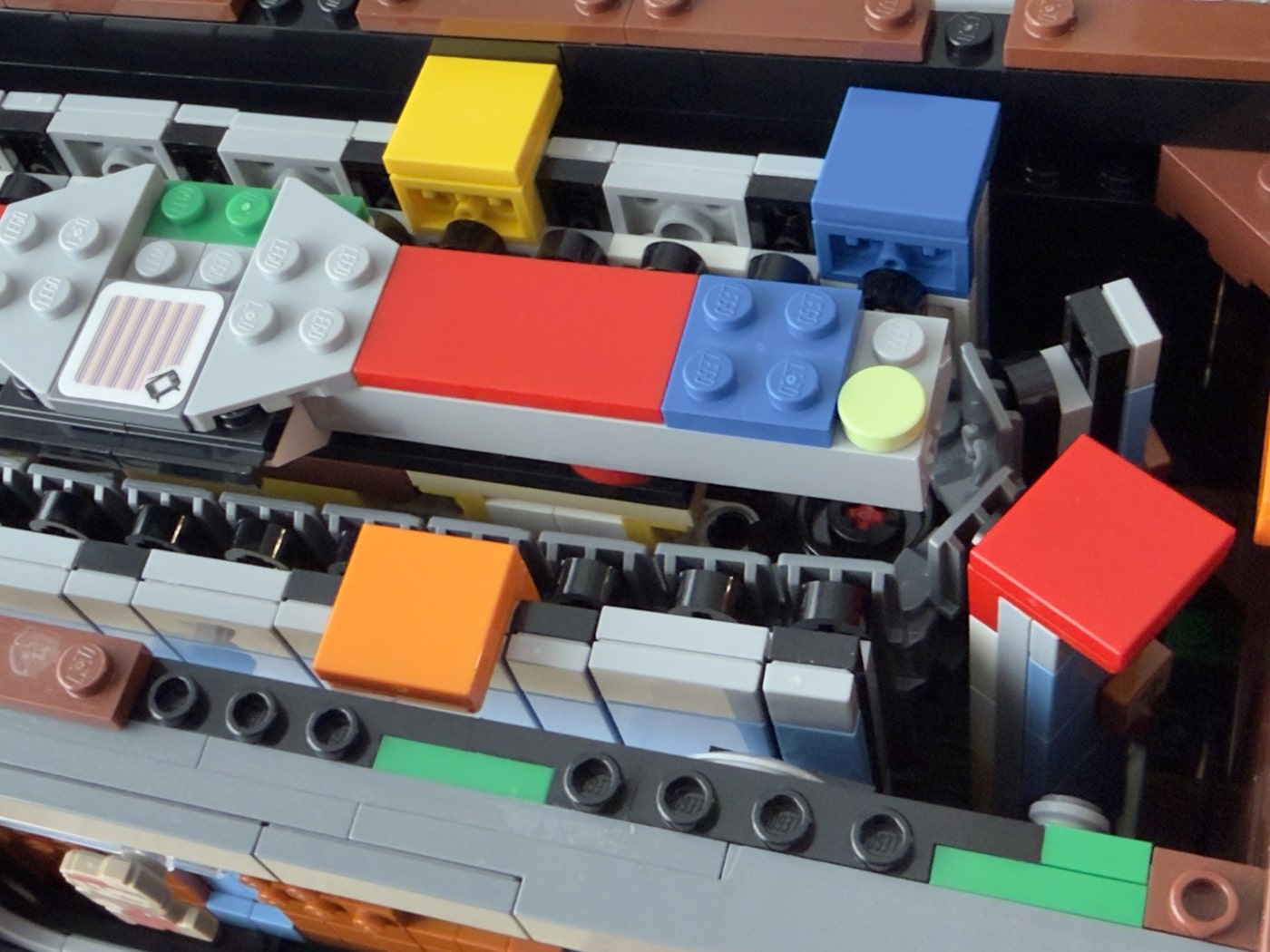

LEGO models would often start with the base, or maybe the core of the part of the model I was currently building. Interlocking bricks would take the weight of the model, eventually, so this part was important.

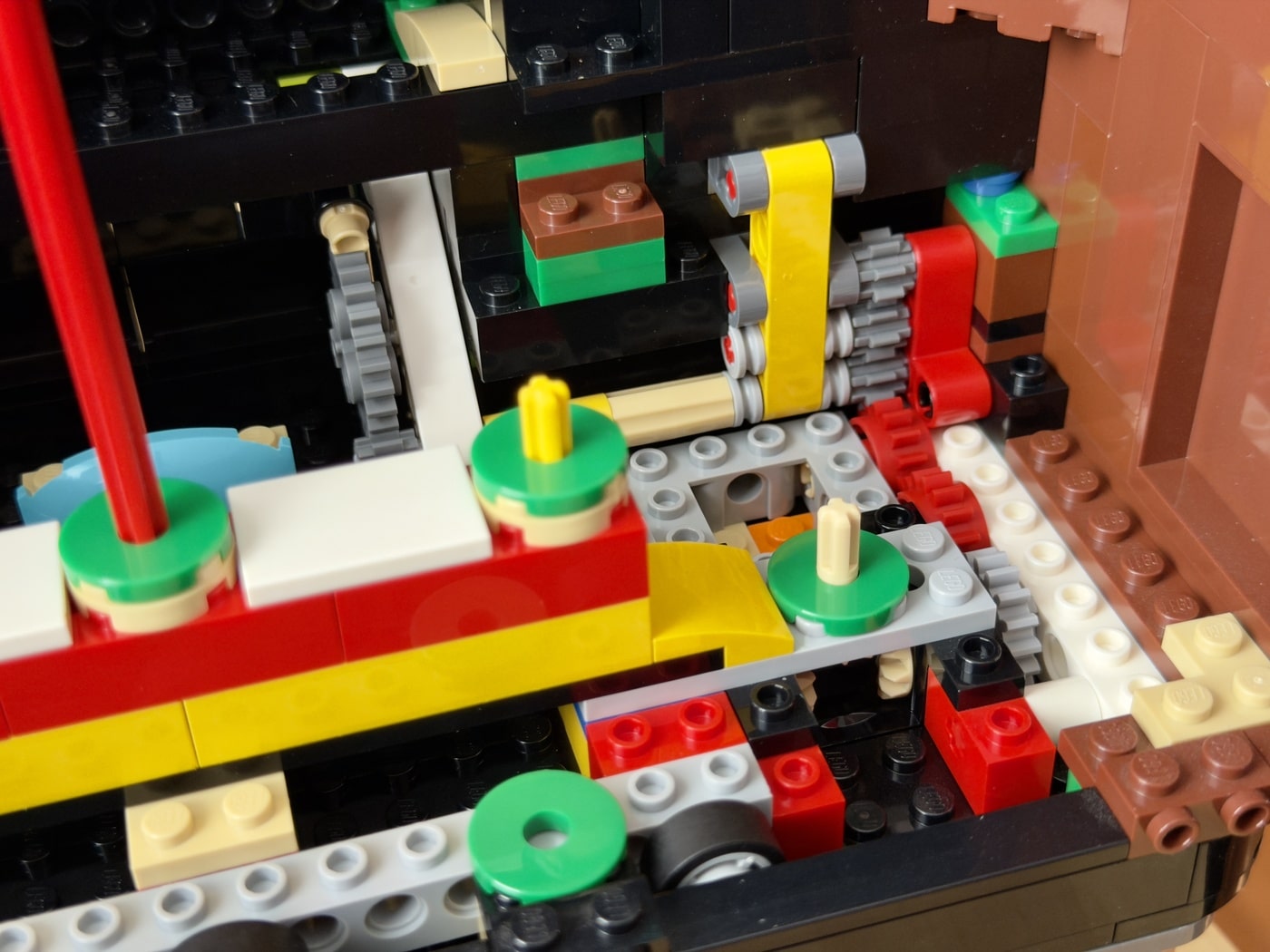

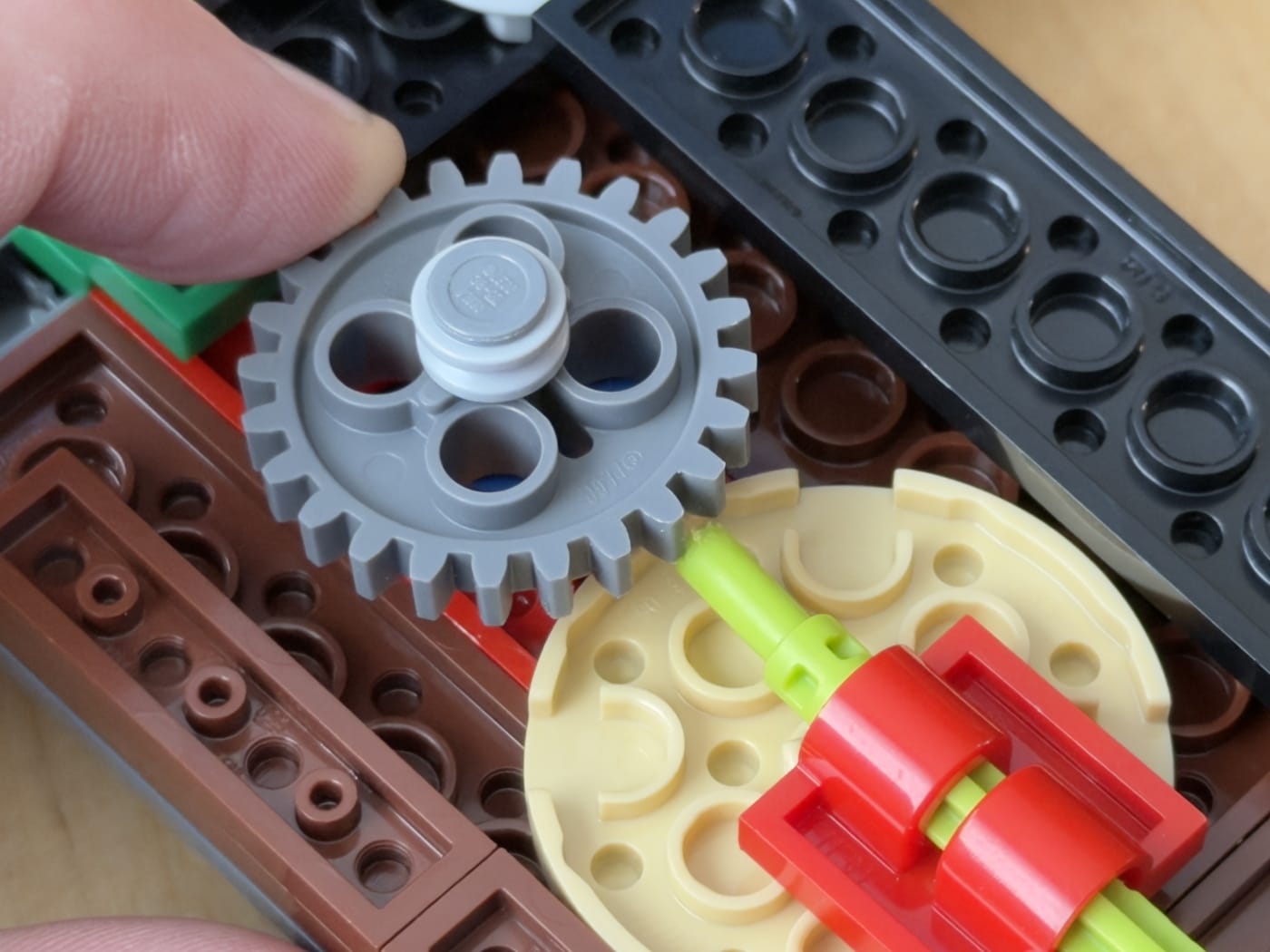

Then, after a bit, there’d be an interesting device. Maybe it’d start with an axle and a gear. Or maybe it was a hinge block. I’d press or slot it in, then pick up the piece and crank it, turn it, or open and close it.

Playing with it as I built it taught me, bit by bit, about all the moving parts that would eventually make up the whole. I wasn’t making decisions about how to build it, just following instructions. My vision of the future was often fuzzy at this point. But I could tell how this piece moved, and what happened when it did.

As the build went on, more devices would interlock with the original. Once again, I’d stop building and experiment with the mechanisms. The more I explored, the more I understood. I developed expertise through that play.

When buildings break

On my way to the end of the build, something would almost always come apart. (With luck, I wouldn’t lose any tiny, invisible pieces to the carpet in the process, only to find them later with my bare foot.) I’d need to fix it.

This is where I leveraged that expertise. I didn’t need to endlessly search through the instructions to figure out how to put it back together. I knew how it fit together, I knew how it was supposed to work. And, I knew where I could pull something else apart to slot it in.

In some cases, I found I could potentially improve on the stability of the mechanism in question to avoid that problem in the future. I understood all the details of how everything worked until that point, so I as in a great position to make them better.

As I built more models, I built up an internal framework for other, similar models worked, too. I’d spot potential problems in some models based on my experiences with those I’d built earlier. I could visualize how to build things that didn’t come in any instructions I had.

While I’m no LEGO master builder, the act of being present and involved in construction and exploration gave me mastery over these models, as well as similar ones. I had the model, and I had an ever-growing mental map of how it worked. That was immeasurably valuable whenever I’d be fidgeting with one and suddenly found I needed to make an impromptu repair.

Building software, building expertise

I’m sure astute readers have already figured out where I’m going with this. The software I’m most effective at building and maintaining is software I’ve been involved in building from the ground up, actively engaging with it and testing it at every step.

That doesn’t necessarily mean I had to design it all. Or even much of it at all, really. It was most important that I was present putting it together.

When I was learning programming back in the day, type-in programs were my jam. I subscribed to Compute! at the time. When a new issue arrived, I flipped straight to the listings for my TI-99/4A. As I keyed in each line of code, I developed a deep understanding of how each program worked.

In today’s era, software often contains many thousands of active lines of code before I even open an editor. So I take a split approach. There are parts of the system are going to be important for me to have deep knowledge about. And there are parts that I think it’s better for me to not invest limited time in.

It’s like how I don’t know the intricacies of injection molding used in LEGO bricks—but I can use them nonetheless. I just need to understand how they fit together and what they can do.

And just as LEGO mechanisms will pop apart sometimes or stop working, or sometimes bricks themselves even break, dependencies I rely on can and do fail. I can fix these sorts of software failures, though often at a high cost. A limited software budget may not be willing to pay that.

Knowing my system, the kind of knowledge that came from building it, is crucial here. I need to find a reliable way forward. I need to be able to work around the deficiencies of the building blocks I’m using. Without the expertise developed building the system, that work can be slow, aimless, and significantly less effective.

Building in modern times

This topic isn’t about AI, specifically. It’s been on my mind for a long time—long before I’d even tried Copilot on for size.

I still build today with the same cognitive engagement I always have. I do use many tools of all kinds to do so—and, this is key: I use them in ways that do not remove me from the builder’s role.

In the case of LLM-based tools, that’s often helping me find what I’m looking for in a large codebase, or suggesting possibilities for a problem I’m stuck on. But I’m always in the driver’s seat.

There is one real problem in modern software development that complicates effective building and understanding. When building LEGO models, I’d turn cranks or manipulate hinges to see how they responded. When building software in the past, I could much more easily do analogous things.

Unfortunately, today, the complexity of running modern software is a serious impediment to the kind of play that is necessary to work with it effectively. Dependency stacks are fragile and poorly-understood, and architectures with large numbers of independently running pieces of software defy debuggability. It takes substantial work to make software transparent, and that work isn’t happening like we really need it to.

Insulating developers from that understanding and visibility leads to software that increasingly only works well in happy paths. It creates failures when they’re most expensive to fix—down the road, when everything’s in production. Investing in development tools and architecture that amplify developers’ visibility and capability in systems is crucial.

Building the future

I think our future as software developers can be quite bright, if we can focus on being the builders, and a sense of play elevating us to the experts.

“LEGO” is actually based on a Danish phrase, “leg godt”—”play well”, in English. Not something I’d realized until writing this post, but something that made me smile when I realized the correlation. Being a real, engaged part of creating software makes not just the software and my ability to work with it better; it’s personally fulfilling, too.

It’s a uniquely human thing, to test and explore what we’ve built, to be dissatisfied with it, to improve it. I—we—want to put it together and see what it can do. Through that, we build better software, we become better stewards of that software, and we become better-prepared to do more as our futures roll on.

May we all, as software developers, build well.