An unusual email arrived in the inbox of a faculty member at the department of archeology at Simon Fraser University in the spring of 2024.

This email was from a thrift shop, Thrifty Boutique in Chilliwack, B.C. — unlike the many queries archeologists receive every year to authenticate objects that people have in their possession.

The shop wanted to determine whether items donated to the store (and initially put up for sale) were, in fact, ancient artifacts with historical significance. Shop employees relayed that a customer, who did not leave their name, stated the 11 rings and two medallions (though one may be a belt buckle…

An unusual email arrived in the inbox of a faculty member at the department of archeology at Simon Fraser University in the spring of 2024.

This email was from a thrift shop, Thrifty Boutique in Chilliwack, B.C. — unlike the many queries archeologists receive every year to authenticate objects that people have in their possession.

The shop wanted to determine whether items donated to the store (and initially put up for sale) were, in fact, ancient artifacts with historical significance. Shop employees relayed that a customer, who did not leave their name, stated the 11 rings and two medallions (though one may be a belt buckle) in the display case with a price tag of $30 were potentially ancient.

Thrifty Boutique wasn’t looking for a valuation of the objects, but rather guidance on their authenticity.

Eclectic collection

As archeology faculty, we analyzed these objects with Babara Hilden, director of Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Simon Fraser University, after the store arranged to bring the items to the museum.

Our initial visual analysis of the objects led us to suspect that, based on their shapes, designs and construction, they were ancient artifacts most likely from somewhere within the boundaries of what was once the Roman Empire. They may date to late antiquity (roughly the third to sixth or seventh century) and/or the medieval period.

The initial dating was based largely on the decorative motifs that adorn these objects. The smaller medallion appears to bear a Chi Rho (Christogram), which was popular in the late antiquity period. The larger medallion (or belt buckle) resembles comparable items from the Byzantine Period.

The smaller medallion appears to bear a Chi Rho or ‘Christogram’ symbol. (Simon Fraser University/Sam Smith), Author provided (no reuse)

The disparities between the two objects, suggesting different time periods, make it unlikely they’re from the same hoard. We expect they were assembled into an eclectic collection by the unknown person (as of yet) who acquired them prior to their donation to Thrifty Boutique.

- ** Read more: Melsonby hoard: iron-age Yorkshire discovery reveals ancient Britons’ connections with Europe ** *

With the exciting revelation that the objects may be authentic ancient artifacts, the thrift store offered to donate them to SFU’s archeology museum. The museum had to carefully consider whether it had the capacity and expertise to care for these objects in perpetuity, and ultimately decided to commit to their care and stewardship because of the potential for student learning.

Officially accepting and officially transferring these objects to the museum took more than a year. We grappled with the ethical implications of acquiring a collection without known provenance (history of ownership) and balanced this against the learning opportunities that it might offer our students.

The larger medallion (or belt buckle) resembles items from the Byzantine Period. (SFU/Sam Smith), Author provided (no reuse)

Ethical and legal questions

Learning to investigate the journey of the donated objects is akin to the process of provenance research in museums.

In accepting items without known provenance, museums must consider the ethical implications of doing so. The Canadian Museums Association Ethics Guidelines state that “museums must guard against any direct or indirect participation in the illicit traffic in cultural and natural objects.”

When archeological artifacts have no clear provenance, it is difficult — if not impossible — to determine where they originally came from. It is possible such artifacts were illegally acquired through looting, even though the Canadian Property Import and Export Act exists to restrict the importation and exportation of such objects.

- ** Read more: HBC’s artworks and collections help us understand Canada’s origins — and can be auctioned off ** *

We are keenly aware of the responsibility museums have to not entertain donations of illicitly acquired materials. However, in this situation, there is no clear information — as yet — about where these items came from and whether they are ancient artifacts or modern forgeries. Without knowing this, we cannot notify authorities nor facilitate returning them to their original source.

With a long history of ethical engagement with communities, including repatriation, the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology is committed to continuing such work. This donation would be no different if we’re able to confirm our suspicions about their authenticity.

Archeological forgeries

Archeological forgeries, while not widely publicized, are perhaps more common than most realize — and they plague museum collections around the world.

Well-known examples of the archeological record being affected by inauthentic artifacts are the 1920s Glozel hoax in France and the fossil forgery known as Piltdown Man.

Other examples of the falsification of ancient remains include the Cardiff Giant and crystal skulls, popularized in one of the Indiana Jones movies.

Various scientific techniques can help determine authenticity, but it can sometimes prove impossible to be 100 per cent certain because of the level of skill involved in creating convincing forgeries.

Sabrina Higgins, SFU associate professor, global humanities and archaeology, and Barbara Hilden, director, SFU Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, examine the items that have been donated to SFU for study. (SFU/Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology), Author provided (no reuse)

Copies of ancient artefacts

Other copies of ancient artifacts exist for honest purposes, such as those created for the tourist market or even for artistic purposes. Museums full of replicas still attract visitors, because they are another means of engaging with the past, and we are confident that the donation therefore has a place within the museum whether the objects are authentic or not.

By working closely with the objects, students will learn how to become archeological detectives and engage with the process of museum research from start to finish. The information gathered from this process will help to determine where the objects may have been originally uncovered or manufactured, how old they might be and what their original significance may have been.

Object-based learning using museum collections demonstrates the value of hands-on engagement in an age of increasing concern about the impact of artificial intelligence on education.

New course designed to examine items

The new archeology course we have designed, which will run at SFU in September 2026, will also focus heavily on questions of ethics and provenance, including what the process would look like if the objects — if determined to be authentic — could one day be returned to their country of origin.

The students will also benefit from the wide-ranging expertise of our colleagues in the department of archeology at SFU, including access to various technologies and avenues of archeological science that might help us learn more about the objects.

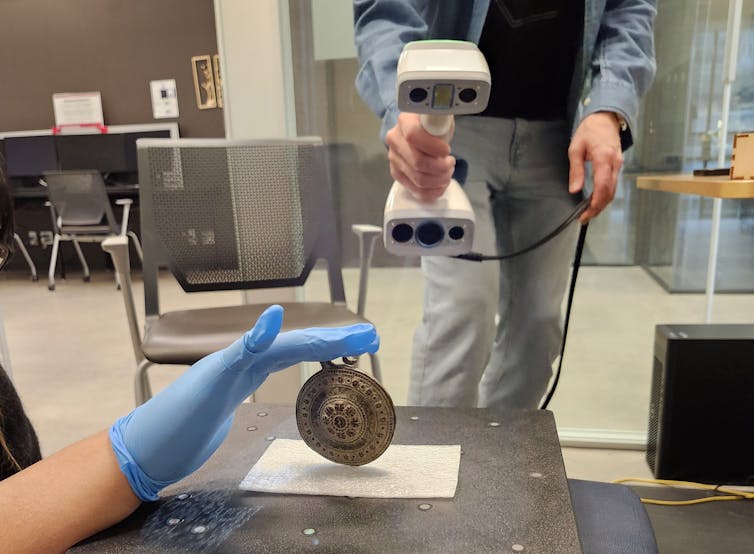

This will involve techniques such as X-ray fluorescence, which can be used to investigate elemental compositions of materials and using 3D scanners and printers to create resources for further study and outreach.

3D scanning one of the items at SFU’s Media and Maker Commons. (Cara Tremain), Author provided (no reuse)

Mentoring with museum professionals

Local museum professionals have also agreed to help mentor the students in exhibition development and public engagement, a bonus for many of our students who aspire to have careers in museums or cultural heritage.

Overall, the course will afford our students a rare opportunity to work with objects from a regional context not currently represented in the museum while simultaneously piecing together the story of these items far from their probable original home across the Atlantic.

We are excited to be part of their new emerging story at Simon Fraser, and can’t wait to learn more about their mysterious past.