Businessweek | The Big Take

India’s Digital Dream, Hacked

India’s digital revolution has exposed millions to a criminal dystopia. This is the story of a neurologist placed under “digital arrest”; a farmer promised a job that would set him up for life; a young man arranging mule bank accounts; and a newlywed who joins the crypto underworld.

December 5, 2025 at 12:01 AM EST

Share this article

1. RUCHIKA.

Lucknow, India. August 2024

She races into her bedroom, shuts the door behind her, then falls to the checkered-tile floor. The only place to hide is beneath the bed. She wriggles under, struggling to keep her smartphone in place so its camera remains trained on her face.

One of the rules s…

Businessweek | The Big Take

India’s Digital Dream, Hacked

India’s digital revolution has exposed millions to a criminal dystopia. This is the story of a neurologist placed under “digital arrest”; a farmer promised a job that would set him up for life; a young man arranging mule bank accounts; and a newlywed who joins the crypto underworld.

December 5, 2025 at 12:01 AM EST

Share this article

1. RUCHIKA.

Lucknow, India. August 2024

She races into her bedroom, shuts the door behind her, then falls to the checkered-tile floor. The only place to hide is beneath the bed. She wriggles under, struggling to keep her smartphone in place so its camera remains trained on her face.

One of the rules she must follow: No visitors. But her uncle dropped by unannounced, and her mother let him in. So here she is, hiding, trying not to make a sound, staring at the phone as it stares at her. On the screen she sees the crest for India’s Central Bureau of Investigation.

She can hear her uncle outside the room, his voice, his footsteps. What if he walks in? She squirms deeper under the bed and waits, for a half-hour, maybe an hour, doing as she’s been told.

Before she received the call, before the caller sent her the 70 rules of surveillance, Ruchika Tandon, a neurologist in the northern city of Lucknow, had a routine: a two-hour swim each morning, an eight-hour shift that often stretched to 12 at one of the country’s top teaching hospitals, guitar lessons in the evening. She’d been a class “topper,” as they say in India, passing every major academic exam on her first try. She took care of her mother and son in the same two-story house with a rusty gate that she’d been raised in. Her life was stable, her days predictable, her bearing unassuming, the expectations of her, met.

Dr. Ruchika Tandon in Lucknow, at the government hospital where she works.

The phone had hijacked that life, its little black eye always on her. It watches her when she washes her face. It watches her when she cooks, and when she finishes, the voice on the other side says, “Now you can eat.” It even watches her when she sleeps. And all those rules, each shrinking the world around her. No turning off the camera. No social media. No texts or calls. No unapproved purchases. No attempting to escape.

2. PRIYA.

Bargarh, Odisha state

Haripriya Pradhan is 31 when she marries in December 2022, nearly a decade older than the average wedding age for women in her home state of Odisha on the Bay of Bengal.

Growing up on the poor side of a poor state, Priya, as she liked to be called, had big plans. She studied for an MBA, made her way to Delhi, and by her late 20s was back in Odisha, leading a small sales team at the branch of a top Indian private insurer.

Online, she presented as a young woman with urban sass. Zara loafers. Converse hoodie. Puckered crimson lips and long, silky black hair, artfully tousled. She posted: #SelfLove #selfcare “Beauty is skin deep but attitude is to the bone.”

A post from Priya’s Facebook page.

In much of India, views on smart, ambitious women can be complicated: Education and careers are important until they aren’t. Ads flood newspapers and Shaadi.com seeking brides who are accomplished, hold advanced degrees, yet are still “homely”—as in, literally willing to stay home once wedded.

It took only an hour for Bholesh Khamari to decide Priya was the one. She had lived “outside,” as he puts it. She had a certain willfulness he attributed to her time in the big city, Delhi. But she also came from a good family and, he thought, shared his values, like a deference for elders.

Priya moves in with her new extended family: her husband, Bholesh, her mother-in-law, brother-in-law, his wife and their child. They cram into a one-story pink house in Bargarh, a sleepy district with a disproportionate number of auto parts shops.

She chafes at her new life. She likes wearing jeans and T-shirts, but women in Bargarh wear saris or dresses. “Why should I change what I’m wearing?” Priya asks Bholesh. In Hinduism, a reverence for food runs deep. It’s not to be wasted. But Priya, instead of giving leftovers to the cows and dogs, tosses the scraps, setting off quarrels with her mother-in-law.

Priya finds escape at a newly opened branch of a small regional bank, working as a low-level manager. It’s a bleak posting in a half-constructed building, and business is slow. That’s all right, because she has other work on the side: She’s joining Telegram and WhatsApp groups on her phone, learning about and investing in cryptocurrency.

Bholesh doesn’t understand why she feels the need to make more money. Between his income as a physiotherapist and her salary, they’re doing well—10 times the state’s average rural household income. “What do we lack?” he asks her.

“It is not how much we have, but how much we enjoy, that makes happiness,” Priya had posted earlier on Facebook. But if one can have more and still enjoy, why not?

There’s a catch: Her funds are frozen. To unlock them, her new Telegram acquaintances say she must send more money. With help from Bholesh and her siblings, Priya cobbles together 2,012,700 rupees ($22,440), a small fortune, enough to construct a house in many Indian cities.

In March 2023, three months into her marriage, Priya checks the details of the 11 payees she’s been instructed to transfer the money to. She types her username, 10881532, into https://oraclecorporation2023.com. Then, she sends it all.

3. GOVIND.

Gonda, Uttar Pradesh state

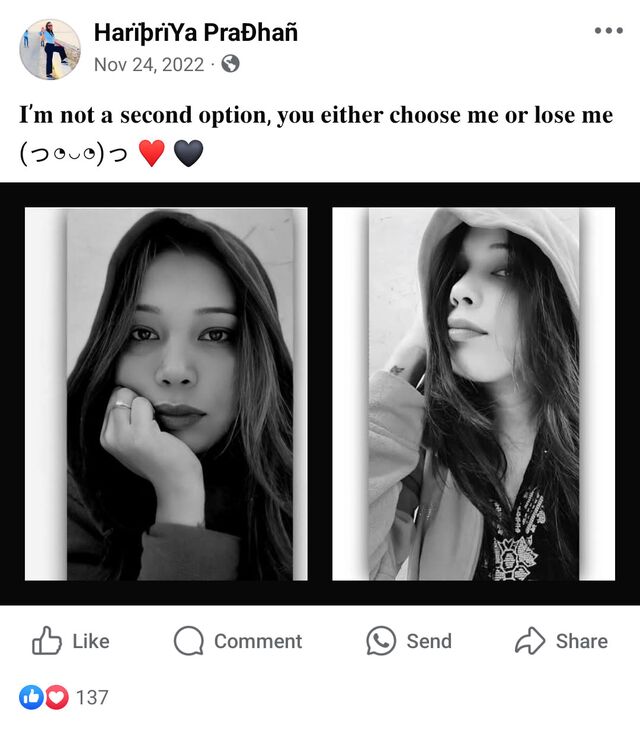

It’s early 2024, and Govind Tripathi stares bleakly across his fields near Gonda in Uttar Pradesh, one of India’s northern breadbasket states. Soon, it would be time to harvest the pulses, wheat and mustard sown during the winter. He needs a bumper crop.

Five years earlier, he’d quietly sold off his wife’s mangalsutra wedding necklace and their gold wedding bands, and taken a 300,000 rupee loan to pay for his mother’s cancer medications. She died a year later, his father soon followed, and with him disappeared the government pension that had supported the extended family.

Half the loan remained, and what Govind needs now is cash. His six acres of farmland, passed down across generations, grows enough to feed the family but not enough to turn a profit. The stray cows don’t help. Since 2014, Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government has sought to end the butchering and trading of cattle, an occupation long dominated by Muslims—even setting up a cow welfare agency in 2019—and the population of stray cows has exploded. Govind, like any devout Hindu, reveres the sacred animals. But this is getting out of hand—the beasts are devouring his livelihood, munching on anything that sprouts.

A farm on the outskirts of Gonda.

Jobs are scarce in his rural village, and Govind is no entrepreneur. He still has a pile of inventory from a clothing shop that never took off. Married at 19, he’s spent two decades working the land.

There’s one opportunity if Govind is willing to travel. He learned about it from Satish and Surendra, two friends who are like family. They grew up together in Gonda. They tell him there’s a decent job in Dehradun, a town in the foothills of the Himalayas about 650 kilometers (400 miles) northwest in Uttarakhand state. They just returned from a gig, and their employers say there’s work again: “Come back with two more friends.”

Something feels off about the offer. Govind doesn’t really understand what the job is—some kind of office work that pays 20,000 rupees a month, almost too generous for someone with his background. It makes him nervous to think of leaving his wife and daughter alone at home for months. He has never lived anywhere but this brick home, built by his father, with its powder blue walls and jasmine tree by the front door.

Govind tries to find resolve in his brother-in-law’s advice: “Nothing happens without trying.”

4. THE WHISTLEBLOWER.

Jalandhar, Punjab state

In 2015, Bharat Bhushan opened a tiny shop with plywood shelves in the northern Punjabi town of Jalandhar. In his early 30s, he was part of a new wave of entrepreneurs bringing basic services closer to millions of Indians. His spare kiosk—computer, monitor, desk and chair—became a lifeline. Locals came to pay electricity bills, top up their mobile phones or book railway tickets, chores that otherwise meant treks to distant service centers or hours in government queues.

Bharat Bhushan at his shop in Jalandhar.

India was on the cusp of a digital revolution that would soon send customers flocking to kiosks like his. Over the previous two decades, the country had shifted from landlines to mobile phones, but cellular services remained too costly to bring India fully online. Then came Mukesh Ambani—Asia’s richest man, famed for spotting opportunities—who upended the market in late 2016 with Reliance Jio. His nationwide 4G network slashed data costs to the world’s lowest, putting high-speed internet within reach of anyone with a cheap smartphone. Prime Minister Modi, too, pledged to knit the country together with high-speed networks under an initiative called Digital India.

The bedrock for that transition was Aadhaar—a new biometric identification system spearheaded by Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of tech giant Infosys. Until 2010, India had no equivalent to the US Social Security number. Many people—mostly poor, often rural—couldn’t prove their identity and were thereby shut out of the formal economy. They couldn’t buy a SIM card, open a bank account or access government benefits. Aadhaar, meaning “foundation,” changed that, issuing a unique 12-digit number linked to a person’s fingerprints and iris scan.

“I think in the next several years India will become the most digitized economy,” Bill Gates told an audience in Delhi in November 2016. “All of the pieces are now coming together,” he said. “It’s a pivotal moment in India’s history.”

Registering 1.3 billion people in Aadhaar proved fiendishly complex. The fingerprints and iris scans of each new registrant had to be compared against those of all previous registrants. To speed the process, the government turned to private operators such as Bharat. In 2016 he took out a loan to buy a biometric scanning machine for 70,000 rupees, then set to enrolling people and printing Aadhaar cards.

Business was brisk. Aadhaar was supposed to be voluntary, but its expediency soon made it a de facto requirement for everything: buying a car, tracking a lost Amazon package, registering on a matchmaking website, getting treated at a hospital. People across the country lined up for an Aadhaar number.

At first, Bharat’s was the only kiosk in the neighborhood. Before long others caught on. Within months, Aadhaar kiosks mushroomed across the country. In Bihar, near the border with Nepal, one entrepreneurial 16-year-old named Rishikesh Kumar opened one, gaining a toehold into a world coursing with the private details of hundreds of millions of citizens.

Operators received little vetting: Inspectors came maybe twice to Bharat’s kiosk, and only to check if there was a water cooler, enough chairs and adequate waiting space, he recalls. For technical support, Bharat and some fellow operators had an informal WhatsApp group where they shared information on software updates and the like.

By late 2016, India had issued more than a billion Aadhaar numbers, opened 260 million bank accounts, and brought 410 million people online in less than a decade. By making it easy to verify identities and link bank accounts, Aadhaar also enabled the rise of a homegrown instant-payment system that began transforming the country’s cash-based economy into a digital one. Street sellers and rickshaw drivers started flashing QR codes to customers, who at a stroke could transfer payment from their phones. Modi accelerated this shift in November 2016 by withdrawing India’s highest-value banknotes, accounting for 86% of the currency in circulation, to combat corruption and tax evasion.

India proved Gates right, undergoing the fastest, most ambitious digital transformation in history. It became the world’s top consumer of mobile data per user. Its Internet users are set to surpass 900 million. Its instant payment system processes half of all global real-time transactions.

The Aadhaar program was lauded by experts for its scalability and security. But it had a fundamental flaw: India had created a lockbox, yet kept giving a peek inside—to telecom companies, banks, courier companies, airlines, you name it.

Even small vendors in India now accept instant payment.

By mid-2017 the government began restricting access for private operators like Bharat. Along with thousands of other small-time entrepreneurs, he was about to lose his livelihood.

Around that time, Bharat noticed new participants in the WhatsApp group, hawking a software they promised would maintain access to the Aadhaar system for a nominal fee of 200 to 300 rupees. “I wanted to try and understand the software, what it was,” Bharat recalls. He purchased it, got a new ID and password, and entered the system. He typed in an Aadhaar number, and the system spat back all the registrant’s details—name, address, phone number, photo. This was odd. Previously, he couldn’t retrieve such details, he could only input them. He tried another Aadhaar number, and another, and another—all with the same result. “I felt something was very, very wrong.”

Over the next few months, he tried to alert authorities. He called and sent hundreds of emails to the Unique Identification Authority of India, which oversees Aadhaar. He went in person to several regional government officers to show them the software firsthand. He even emailed Modi.

For about $3.50, Bharat had bought access to a database containing the private details of a billion-plus people, one of the biggest data breaches of all time, and no one cared. Eventually, Bharat got the attention of a local newspaper reporter, who replicated Bharat’s steps, verified the breach and published an account. Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party responded by tweeting from its official account, “FAKE NEWS.”

It’s unknown how many unauthorized people had access or how much data was downloaded. In 2023 an American cybersecurity firm discovered hundreds of millions of Aadhaar records for sale on the dark web. Unlike leaked passwords or credit card numbers, biometrics can’t be changed—once they’re stolen, they pose a lifelong risk.

The day after the newspaper story was published, Bharat was rewarded for whistleblowing by having his access to government services cut off. He folded his service center and opened a business repairing kitchen appliances. Unauthorized groups are still out there offering access to Aadhaar, evidence that the government’s ID system remains vulnerable, he said in June at his new shop. “They know what’s happening, but they can’t stop it.”

5. RUCHIKA.

Aug. 1, 2024

Ruchika, the neurologist, is running late one Thursday morning in August of 2024 when the call comes at around 8. Normally, she’d be swimming her laps. It’s still early for a call, but it might be a patient. She presses the button on her keypad phone to answer.

A man says he’s calling from the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. Your number is being suspended, he says, telling her that 22 criminal complaints have been registered against her number. Is she aware of these complaints? No? Someone may be using her personal information fraudulently, he says. He’ll transfer her to the Central Bureau of Investigation, or CBI.

The voice of another man comes on. He identifies himself as Rahul Gupta, chief investigation officer, badge number FA263521. He speaks sternly, sparsely: She’s a suspect in a criminal case involving the collapse of Jet Airways, India’s second-largest airline. Ruchika vaguely recalls the headlines from a year earlier, when investigators arrested the founder, Naresh Goyal, on allegations that he’d laundered money siphoned from the airline’s bank loans. Gupta tells her there’s evidence, including an audio recording, that her accounts were used to launder funds.

Ruchika’s mind blanks. This must be a mistake. At 41 years of age, she’s never set foot in a police station, never received a traffic citation. She’d become a doctor by abiding by the rules, slogging through the rigid syllabi of India’s education system. Just four nights earlier, she was in Delhi, accepting an award for her research into movement disorders and Parkinson-plus syndromes. What’s going on?

But Ruchika isn’t getting time to think. Inspector Vijay Khanna from the Mumbai Cyber Crime office is now on the line: He has a warrant for her arrest, and local police are on their way. They’ll reach her home in five minutes.

There’s one alternative: Ruchika could agree to be placed under “digital custody” and interrogated remotely over Skype. But her case falls under India’s Official Secrets Act, so she can’t mention this to anyone, not even her mother or son. She must make a decision—quickly, Khanna says.

What would people think if she were taken away handcuffed by police? What would that mean for her son? I’ll take digital custody, she tells Khanna. But she can’t get on Skype—she doesn’t use a smartphone. Go out and buy one, he instructs. Otherwise, we’ll have to arrest you.

Ruchika recalls there’s an electronics store nearby on a busy circle next to the metro stop. She goes as soon as it opens, at 11 a.m., and picks out a black Samsung Galaxy F15 with a glossy 6.6-inch display. Make sure you install Skype, Gupta and Khanna had instructed. She asks the store clerk to help download the apps.

Until now, Ruchika had avoided upgrading to a smartphone. Everything was moving online—bill payments, shopping, access to bank accounts. Everyone wants you to download this app and that app to transact. Even her patients didn’t want to come to the hospital anymore; they wanted to do things over WhatsApp. Not trusting that world, Ruchika had clung to an old keypad phone with a cracked screen. But now, she has no choice.

Back at home, she fumbles with the new phone, struggling with its touchscreen and swipes. Somehow she launches Skype. They can see her, but all Ruchika sees is a red and navy logo with three golden lions in the center—the CBI’s official crest. In the tiny print below the lions, it says, “Satyameva Jayate.” Truth alone triumphs.

The voice on the other side begins to interrogate her.

See the graphic novel of Ruchika’s digital arrest.

6. GOVIND.

Dehradun, Uttarakhand state

In mid-2024, Govind, the farmer, and three companions from Gonda board a train that rattles northwest for 14 hours to Dehradun. Waiting for them is Robin Kumar. In his mid-30s, with a slight limp and a fast mouth, Robin informs them of their new employer: a transport company, GKGT, that’s setting up a branch in the Himalayan city.

Their new workplace is a ground-level office with nothing but a plastic signboard, a table and four chairs. Robin assures them that more equipment—laptops, printers—will soon arrive. But first he needs Govind’s Aadhaar card and his mobile phone.

Over the next few weeks, Govind discovers his main job seems to be opening accounts at local banks. Robin takes him to fill out form after form, opening corporate accounts under his name as GKGT’s director. Back at the office he waits for bank employees to drop by to verify that the business is legitimate. When they come, it’s all in English, and Govind has trouble following. But Robin and the bank staff appear to know each other and tell him to just keep signing. When mailings arrive—ATM cards, passbooks, checkbooks, all in Govind’s name—Robin keeps them.

Govind doesn’t like this, but Robin says: “The company is in your name, but someone else is investing the money—obviously, they’ll keep the account.” Plus, he needs control of the accounts to pay their salaries, he says.

Govind Tripathi at his house in Gonda.

As promised, Govind receives 20,000 rupees a month plus room and board. One long weekend, with the banks closed, Robin rents a car and drives them north for a pilgrimage to Kedarnath, a mountain temple snowed in for half the year. Govind helps Robin, who struggles with his limp, up the 17-kilometer trek to the temple; Robin buys Govind an amulet of three rudraksha seeds beaded onto a crimson string. They pray to Lord Shiva, both Protector and Destroyer, then return to Dehradun for more rounds of bank account openings.

Govind can’t shake the feeling that something is amiss, but Robin and his boss, who occasionally drops in from out of town, have an answer for everything. Some accounts aren’t working so that’s why they keep opening new ones, they explain. GKGT is registered under Govind’s name to minimize the company’s goods-and-services tax, they say. Just imagine, Robin tells Govind: Once the business takes off, you’ll get a share of the profits. “There’s not even a 1% problem in anything we’re doing,” Robin says, pulling up photos on his phone of GKGT’s fleet of trucks.

Then, about two months in, it’s over as quickly as it started. Robin informs the group that GKGT is having trouble sorting out the goods-and-services tax issue so they can go home for a month. Govind, flush with three months’ salary, returns to Gonda, relieved that his doubts appear unfounded and comforted by what Robin told him: “Don’t worry, we’ll set you up for life.”

7. RUCHIKA.

Aug. 2, 2024

It’s Friday, and Ruchika sits in her bedroom, isolated. Her new phone pings as a document lands in her WhatsApp. It’s watermarked with the CBI logo and carries Officer Gupta’s stamp and signature. *“Consent to Terms of Digital Custody … This case is classified as a second-level confidential case by the state. Anyone who leaks the secret will be sentenced for 3 to 5 years in prison …” *

On it is printed her confidential Aadhaar number.

Another ping. This time, it’s a list of 70 surveillance rules. The suspect must not alter her appearance. The suspect must not communicate with unauthorized individuals. The suspect must provide updates on her activities. Suspect, suspect, suspect. The word jars her.

It’s early evening now, and Inspector Khanna pops onto Skype. Unlike Gupta, Khanna seems sympathetic. He reassures her that if she’s innocent this will all blow over—but she needs to cooperate. He speaks in English, fluently. He begins asking questions, the kind you hear in a psychological test.

“What is your biggest fear?” “What do you consider your greatest accomplishment?” “How do you deal with failure?”

This goes on for hours, until 2 a.m. He asks about 500 questions in all.

The most rational mind will bend under stress. Isolation and confinement can cloud judgment. Relentless surveillance can impair cognitive functioning. Under prolonged interrogation, people do something that in retrospect makes no sense—they give false confessions.

Ruchika, under all these stressors, doesn’t find it odd that “Vijay Khanna” is almost comically fitting—a name that generations of older Indians associate with the swashbuckling police inspector played by Bollywood great Amitabh Bachchan. When Khanna says he can’t show Ruchika his face on Skype because he’s an intelligence officer, she believes him.

By the time Khanna breaks for the night, he knows Ruchika’s fears and desires, her strengths and weaknesses. A night duty officer comes online. Ruchika will remember her voice, the only female one she’ll hear on Skype. The officer doesn’t say much. As Ruchika cries herself to sleep, the little black eye watches her.

Ruchika wakes the next morning. It’s Friday, only 24 hours since the first phone call. She’s instructed to change into all white, to show respect. And don’t cry, Khanna says—that will exasperate the court. In her living room, where she sometimes keeps a colorful pile of teddy bears and other stuffed animals, she’s to attend a virtual hearing presided over by D.Y. Chandrachud, the chief justice of India. She’s told to stand. She hears a door open and close, footsteps, a clerk calling the court to order, the crack of a gavel. Chandrachud’s photo appears on Skype.

“Do you know Naresh Goyal?” the voice from the bench asks, referring to the disgraced founder of Jet Airways.

“No.”

“The court has a recording of you speaking with him.”

“I don’t recall,” Ruchika says. “He may have been a patient—my patients often call and talk to me.”

“It was about money.”

An order comes down afterward: “Upon review of the petition filed by Ruchika Tandon, the court finds that the funds in question remain unverified.”

All of Ruchika’s assets must be scrutinized by the CBI for links to illegal activities, the court order says. As a precaution, her funds must be pledged to the court—all of them, fixed deposits, mutual funds, even her retirement fund. She is to transfer them to a government-administered “Secret Supervision Account.” If Ruchika doesn’t comply, the order says, “an arrest warrant will be issued immediately.”

8. THE ECONOMIC DIVIDE.

Mumbai, Maharashtra state

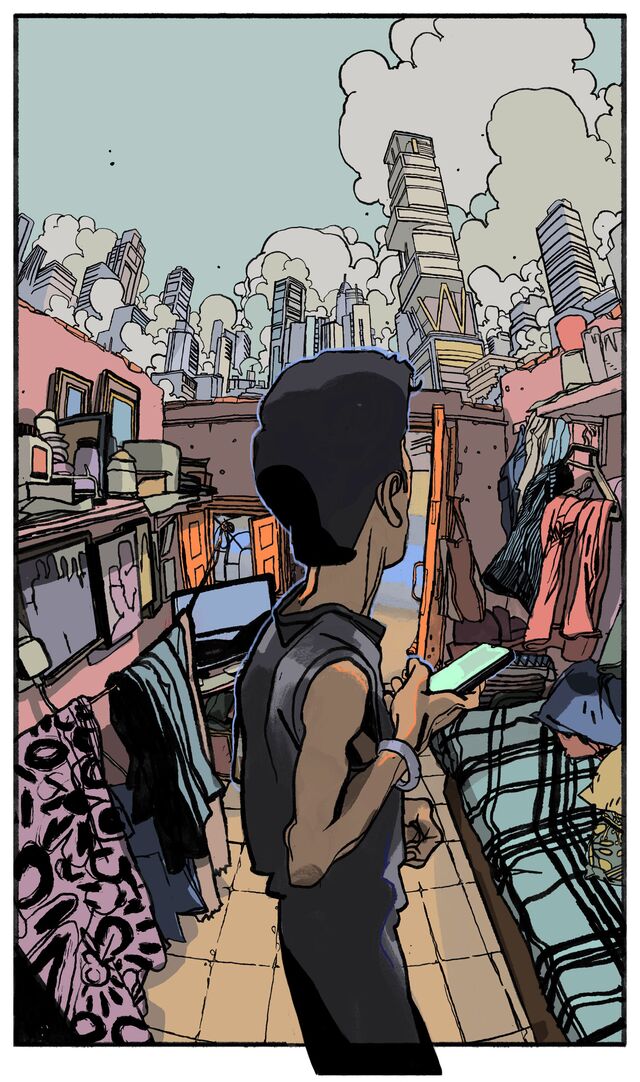

In 2022, the unemployment rate among young college graduates in India was 29%, nearly nine times higher than the rate among illiterate workers, according to the International Labor Organization. Many young people can’t find work that matches their skills and aspirations. For the scam industry, that’s become something to exploit.

Chetan Kokare’s story is a case study. In Mumbai, two worlds face off across a patch of blue sea. On one side is a strip of luxury bungalows and glass towers known as Billionaires’ Row. On the other lies Geeta Nagar, a slum lined with plastic jerrycans where, on average, 10 residents share a community tap that comes alive for 45 minutes—on a good day.

Chetan grew up in Room No. 147 of Geeta Nagar with his two brothers, mother and father. His mother was a house maid, his father a driver. Their $45-a-month room, 12 by 5 feet, had one queen-size bed, a clock and a calendar. It had no shower, no toilet, no tap. A plywood board wedged under the door blocked the entry of rats.

Chetan Kokare grew up in a slum across the water from Mumbai’s Billionaires’ Row.

Across the bay from Chetan’s room was a 27-floor residence, staggered like a Jenga tower, that belonged to Mukesh Ambani. Named Antilia, after a mythical Atlantic island, it had a staff of 600, helipads, gardens, pools, an ice cream parlor, a six-floor garage and a room with walls that emitted artificial snowflakes. Chetan was 18 when Ambani launched Jio, unleashing a digital revolution.

As the eldest son, Chetan worked to bolster his job prospects and improve his family’s fortunes. He earned a commerce degree and an online MBA, and took certification courses in taxation and data processing. He learned English, the language of social mobility. He got jobs, including one in sales with Jio. But it wasn’t enough. The jobs offered no career growth, and even Jio—which means “to live”—never paid more than $150 a month.

Then, one day, an acquaintance of his father’s said he could place Chetan in a job in Cambodia that would pay $700 to $800 a month. But the family would have to front $4,500 in fees to get him there. Desperate, they took out loans. In June 2024, Chetan flew to Siem Reap with a letter assuring him of a managerial job. Upon arrival, he was driven to a five-story building in Poipet, a city on the Cambodia-Thai border, where his passport was taken and he was handed a three-page script to memorize. His new job was to manage “Line 1” of a scam operation, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., seven days a week.

Each day, an automated system would dial for Chetan the numbers of about 100 Indians and play a prerecorded message: “To know more about the status of your undelivered FedEx package, press 1.”

When someone answered, Chetan, posing as FedEx employee Rajkumar Rao, said a parcel linked to their Aadhaar card, containing drugs, had been intercepted by customs and was now in police custody. Then he forwarded the call to “Line 2,” a room replicating an Indian police station, complete with Mahatma Gandhi’s portrait, the buzz of walkie-talkies and a Pakistani man in uniform who placed the person under digital arrest. “Line 3” was manned by someone posing as a finance official who directed the victims to transfer their money to India’s central bank. “Line 4” worked in the background, arranging bank accounts and overseeing transfers and withdrawals.

Chetan’s center, run by a Chinese boss, was staffed by people from India, Cambodia, Nepal and Pakistan. When Chetan botched a call, he was forced to stand for 24 hours or write the script 50 times. For every successful scam, he received a 1% to 2% commission. He was promoted to Line 2, bought the latest iPhone and sent money home.

After five months, Chetan and other line workers confronted the center’s managers, retrieved their passports and left. Chetan returned home in late November. Ten days later, police showed up in Geeta Nagar and arrested him. For 30 seconds of one victim’s 12-day digital arrest, the Skype ID used had been Chetan’s. In April, out on bail, he sits in his home wearing track pants and a black Batman T-shirt. If convicted, he could face life imprisonment. “We have nothing now,” he tells a Bloomberg Businessweek reporter when she visits. “I have to start from zero.”

9. PRIYA

In early July 2024, Priya and Bholesh pose for photos at the Hills n’ Horizon Resort in Nepal—relaxing on lounge chairs by the pool, sipping drinks at the billiard bar, stealing a kiss beneath the outdoor gazebo.

Vacation photos from Priya’s Facebook page.

Over the last 18 months, Priya has played the part of a young Indian wife, fasting during sabitri brata for the long and healthy life of her husband and donning a sari to celebrate the new rice harvest with in-laws. But tensions are building in the marriage.

When it became apparent that the small fortune she’d sent for the crypto investment wasn’t coming back—that she’d been scammed—she filed a police report, to no avail. Her mother-in-law keeps needling her about the loss. Her family insisted she quit her job at the bank, so they could keep watch over her. Trapped at home, Priya is forbidden by Bholesh from trading on her phone.

But Priya is hooked. She’s joined more than 40 Telegram groups and has built a network of contacts, who take Indian rupees and exchange them online for Tether, a cryptocurrency pegged to the US dollar. Tether is both stable and anonymous, making it a favorite of criminals around the world. She begins to work with a group of university boys in Lucknow, known for running their trades during class. One, Ayush Yadav, nicknames her “P2P Aunty” in his contacts—a nod to decentralized peer-to-peer exchanges where people trade crypto anonymously without a middleman.

Bholesh pleads with Priya to stop. This work makes him uneasy. He’s a simple man from a simple family with simple tastes. When he brings up the money lost to the scam, Priya snaps: “It happened just once. How many times are you going to keep bringing it up?” She isn’t the kind to self-flagellate. Her Facebook remains full of pick-me-ups like, “By loving yourself, you’re going to be a happy person.”

“Who knows where this money is coming from,” Bholesh warns her. “It may come from a bad source.”

She ignores his pleas. When the couple returns from their road trip in mid-July, Priya resumes chatting with Ayush on WhatsApp. “Is no work going on today?” Ayush asks. “No, there’s no money these days,” she responds.

About a week later, Ayush pings her. “One guy is going to run a scam,” he writes. “With you.”

10. RUCHIKA.

Aug. 3, 2024

Ruchika clutches the stick shift of her aging hatchback, her mother beside her. After yesterday’s court order, Khanna learned that a good chunk of Ruchika’s assets were held in joint accounts with her mother. That meant the mother had to co-sign on any withdrawals. So Khanna let her know her daughter was in trouble—and that she had to cooperate. “This is a matter of how the next 20, 30 years of your daughter’s life are going to be,” Khanna told her.

Ruchika must transfer all her assets to the secret government account by 4 p.m. today, the court said. Their first stop is a State Bank of India branch.

Ruchika receives instructions on WhatsApp as she arrives. She’s to provide updates to her handlers every five minutes. Her phone pings as the details of the first secret account land. Remember to request real-time gross settlement, RTGS, a system used to transfer large sums of money instantly, the handlers say.

The women are ushered to the office of the branch manager, Naren Kartikey. He remembers Ruchika from earlier visits—reserved and earnest, with a habit of bobbing her head when speaking.

He offers them tea as he looks over the request. The women want to clear out their entire balance: 11.7 million rupees, more than $130,000.

It’s a large amount for India, even for an established doctor. That’s because it’s not just Ruchika’s money—it’s a nest egg built across three generations, beginning with her grandfather, born in the 1920s when India was still a part of the British Raj. A government employee, he’d saved enough through India’s four-decade experiment with a planned economy to build a middle-class life. Ruchika’s father built on that as a civil engineer, squirreling away savings during India’s tumultuous post-independence history, including wars with Pakistan, food shortages, and Indira Gandhi’s two-year rule-by-decree. As Ruchika’s mother aged, the nest egg fattened a little more thanks to a modest pension. In all, Ruchika’s family has saved some 25 million rupees, or about $300,000.

“May I ask, what are you planning to do with this money?” Kartikey asks Ruchika. She’s prepared for the question. The handlers told her to say she was buying property.

But Kartikey asks more questions. Where is this property? Do you really want to use all your liquid assets? Might you consider a home loan? Ruchika hates to lie, but her mind is spinning. She had asked Khanna who her accuser was—who had named her as a suspect—and he’d told her: It might be a co-worker at your hospital. Or a patient. Or maybe someone inside your bank.

Kartikey is also troubled. Ruchika always came across as reticent, but today she seems afraid, anxious. He recalls the funny old keypad phone she used to carry. Now, she has a smartphone and keeps glancing at it, as though someone were on the line, he thinks to himself.

If this were a male client, Kartikey would press more. But Indian mores make it uncomfortable for him to pry into the affairs of two women. Ruchika is a senior faculty member of the hospital, not the type to grill. He processes the request.

Ruchika still has time to make a run across town to the next bank. By day’s end, 14.5 million rupees of the Tandon family nest egg have been whisked away, landing in three separate accounts, including two—opened just weeks earlier in the Himalayan town of Dehradun—registered to a transport company, GKGT.

11. RISHIKESH.

Sitamarhi, Bihar state

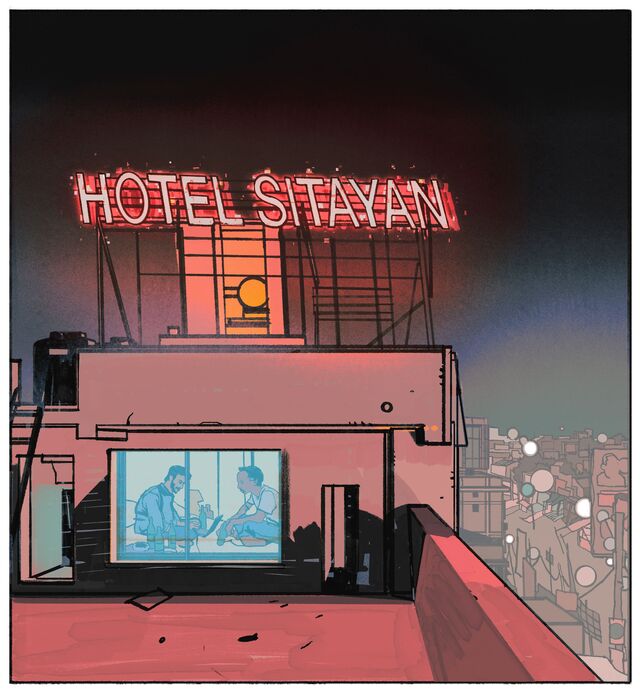

The same day Ruchika stands up in her Lucknow living room for a court hearing, a group of young men check into the Hotel Sitayan in Sitamarhi, a chaotic border town in Bihar state, abutting Nepal.

The four-story building is like thousands cropping up in India’s hinterland, a mishmash of new amenities and creaking infrastructure slapped together to keep pace with the country’s rapid modernization. An open fuse box in the stairwell bursts with electrical wires, ceiling panels are missing in the hallways, and guest rooms on one side look out at two white porcelain toilets that, somehow, made their way onto the tin roof of the building next door.

Hotel Sitayan, home base for one digital-arrest operation.

The Hotel Sitayan is also kitted with flat-panel TVs, air conditioners, and, more important, stable Wi-Fi. For Sitamarhi, it’s top-notch. The men take two rooms at the far end of the first floor, order chicken thighs and half-liter bottles of alcohol, and settle in for the job.

Rishikesh Kumar, a ganja-smoking 25-year-old, takes a room to himself and sets up his laptop. Eight months earlier, he’d responded to a post on a Telegram group of about 10,000 people that served as a kind of marketplace for Indian bank accounts. It brimmed with ads seeking to borrow accounts—preferably corporate ones with large transaction limits—for two to four days. In return, the account holder gets 1% to 2% of whatever funds flow through. One such ad shows bricks of cash covering a bed, set against the track of Paisa (Money), a rap about being as rich as Bezos, Gates and Musk.

Rishikesh is resourceful. As a 16-year-old, he’d started an Aadhaar kiosk—much like Bharat’s in Jalandhar—and got to know others doing similar work. When he saw the Telegram ads, he tapped into that network. One former kiosk owner lined up a contact who promised to provide a corporate account. Rishikesh and the man connected and struck a deal, leading him here.

Overseeing this operation remotely is Gopal Kumar, in his late 20s, who grew up in a small, dusty Bihari town called Barh. (He’s no relation to Rishikesh.) As a child, Gopal was precocious; good at math, a bookworm, the only one in his family to read newspapers in English. In his late teens, he became his family’s best shot at a stable middle-class life, clearing the competitive Indian Navy entrance exam. But over the years he’d strayed, according to two family members. He quietly took leave from the navy, snubbed a request from his eldest brother to meet a potential bride and fell in with company that was a bit “420”—as in, Section 420 of the Indian penal code, Cheating.

Gopal evolved into a potty-mouthed fast talker and a mentor of sorts in the shady world of loaned bank accounts. In one phone-tapped conversation, a person identified by police as Gopal coaches a rookie:

Voice 1:* I have a piece of bad news Gopal: What happened? Voice 1: Account has been frozen Gopal: Sister-f—er! *

Asked what to do, Gopal instructs the rookie on how to bully and motivate the account holder—“You tell him, ‘What sort of account did you give me?’”—then, at the conversation’s end, he agrees to handle the matter himself in return for 200 in Tether and a new smartphone.

Gopal’s operation relies on months of preparation, dozens of people across India, and technological and financial mastery. Weeks earlier, in Dehradun, Robin had covertly installed an app on Govind’s phone that automatically forwarded one-time passwords from his bank accounts. Now Gopal preps Rishikesh with a software called Panel, with which he’s able to manage both those hundreds of one-time passwords and all the bank-accounts-on-loan. Although remote, Gopal is hands-on: call records show the day the group checked in, he spoke with them 25 times over six hours.

Some teams in this underworld lose their proceeds because of glitchy software or an unstable internet connection. In one digital arrest case, more than 5 billion rupees got stuck in a dead man’s account.

Not Gopal’s team. The next day, 5.94 million rupees from the Tandon family nest egg lands in one of Govind’s GKGT company accounts in Dehradun. Govind himself is hundreds of kilometers away, according to call records, unaware of the activity in his account. As Rishikesh monitors Panel, the software executes more than 700 transactions in seconds, redistributing the money in real time to dozens of preregistered beneficiaries, account records show.

With each passing hour, Ruchika’s money becomes, for all practical purposes, irretrievable, traveling through layer upon layer of accounts, dispersing into the ether.

12. RUCHIKA.

Aug. 4, 2024

It’s Sunday, three days since the first phone call, and Ruchika is exhausted. She’s been closing out her deposits, investment policies and retirement accounts, running from one bank to the next. It seems her handlers are always waiting for a notary to sign off on one document or another—she can hear them typing over Skype—slowing everything down.

She keeps wondering: Why would someone accuse her? What reason would anyone have to resent her? She’s not rich, she doesn’t wear fancy jewelry, she drives an aging Maruti Suzuki with vinyl seats. Why is this happening to her?

At times, Khanna, the police inspector, gets fed up with her tears and questions. But other times, he softens and calls her “sister,” promising to help fast-track her bail application. He’s the only one who seems to believe her. They’ve been speaking for hours and hours—under different circumstances, long enough perhaps for a budding friendship—and at times he seems concerned for her well-being, for her future.

Ruchika hears her son leave the house for a dance recital. She was supposed to perform, playing the guitar, but Khanna won’t let her go. He can see she’s upset.

He suggests she play the songs anyway—at home, now.

Ruchika strums through the four songs she was supposed to perform. When she gets to Give Me Some Sunshine, from the 2009 Bollywood blockbuster 3 Idiots, Khanna’s voice cries out on Skype, joining hers:

Give me some sunshine Give me some rain Give me another chance I want to grow up once again

He’s off tune, absolutely terrible. Ruchika tries not to giggle. Momentarily, her tears dry.

13. SCAMDEMIC

As early as 2022, Chinese students in Ireland and Germany were receiving calls from fraudsters posing as Chinese cops, telling them they’d been implicated in a criminal case and instructing them to post “bail” to avoid arrest. By 2024, US colleges were flagging a warning from the FBI about the tactic. Similar alerts sounded in Japan and Thailand. The scam percolated, then petered out.

In India it morphed into an epidemic. Some 40,000 cases were reported in 2022, 60,000 the next, then nearly 124,000 in 2024. As of February this year, Indian citizens had lost 26 billion rupees in digital arrests, as the scam is called.

“Cybercrime has gone from a distant threat to a pervasive, everyday reality,” the government’s main policy think tank, Niti Aayog, said in April. Cybersecurity lapses have also exposed voter ID numbers, health records, even the biometrics of police officers.

Digital arrests draw on an understandi