Steel punch testing of 3D printed metal objects [Source: Materials Research Express]

Steel punch testing of 3D printed metal objects [Source: Materials Research Express]

A new study uses miniaturized small punch testing to probe the mechanical behavior of 3D printed stainless steel, a promising route to faster and less wasteful qualification in metal AM.

Small punch testing (SPT) is a miniaturized mechanical test that presses a spherical indenter through a clamped, thin metallic disc to generate a load–displacement curve. From that single curve, practitioners often back out estimates of yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, ductility, and fracture energy. Because it consumes little material, SPT has long been attractive for in-service components and heritage alloys where sampling mu…

Steel punch testing of 3D printed metal objects [Source: Materials Research Express]

Steel punch testing of 3D printed metal objects [Source: Materials Research Express]

A new study uses miniaturized small punch testing to probe the mechanical behavior of 3D printed stainless steel, a promising route to faster and less wasteful qualification in metal AM.

Small punch testing (SPT) is a miniaturized mechanical test that presses a spherical indenter through a clamped, thin metallic disc to generate a load–displacement curve. From that single curve, practitioners often back out estimates of yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, ductility, and fracture energy. Because it consumes little material, SPT has long been attractive for in-service components and heritage alloys where sampling must be conservative.

Metal additive manufacturing routinely faces the opposite problem of traditional metallurgy — lots of process variables but limited testing stock. Coupons take build volume, tensile bars are wasteful to machine, and microstructure can vary part to part, layer to layer, and across the build plate. A miniaturized method that can be cut from thin walls or small features could unlock far denser property mapping without compromising parts or throughput.

Why This Matters For Metal AM

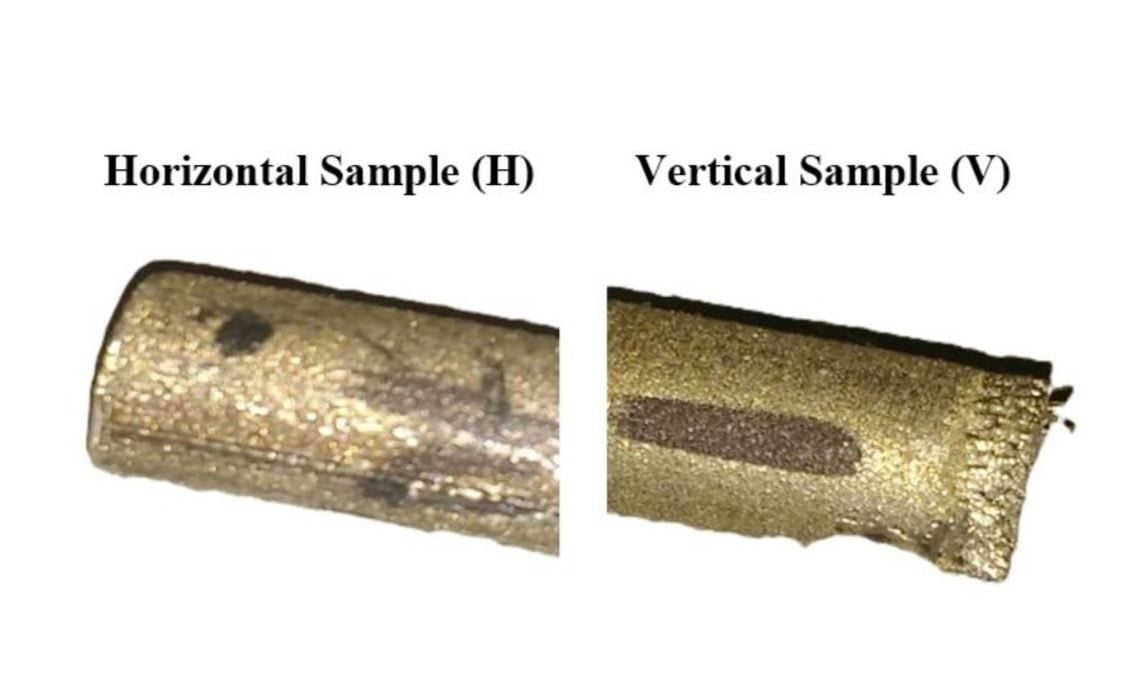

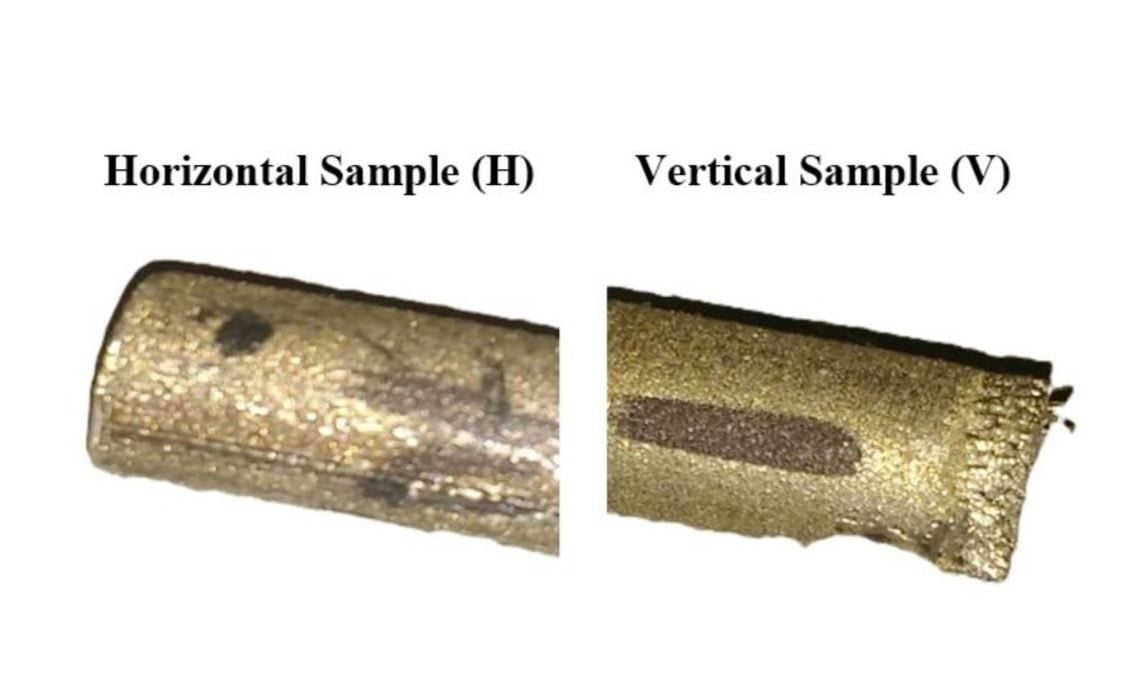

The paper focuses on 3D printed stainless steel, a mainstay of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) and other metal AM processes thanks to its weldability, corrosion resistance, and stable austenitic microstructure. Stainless steel also highlights AM realities: anisotropy from scan strategies, residual stress, porosity, and property shifts after stress relief or hot isostatic pressing.

Conventional qualification relies on full-size tensile tests that are expensive in machine time and human touch. Miniaturized SPT could enable more tests per build, rapid comparison of orientations, and localized checks near critical features. For service bureaus and production shops, that suggests a pathway to tighter statistical control without a steep penalty in time or powder.

What Small Punch Testing Can Reveal

In practice, SPT produces a characteristic curve that transitions from elastic response to membrane stretching and ends in fracture. With calibration, inflection points and areas under the curve can correlate to yield and tensile strengths, while maximum displacement and energy to failure tie to ductility and toughness. That creates a compact proxy for multiple standard tests.

The authors evaluate whether those correlations hold for 3D printed stainless steel, where microstructural features — melt pool boundaries, cell or subgrain structures, and pores — can alter deformation pathways compared to wrought materials. If correlation factors remain stable across build orientations and post processing, SPT could become a fast-screening tool for process development, parameter changes, and lot-to-lot powder checks.

Constraints And Unknowns

There are caveats. SPT correlations are not universal; they require calibration against conventional tensile data for each material condition. Disc thickness, surface finish, residual stresses from cutting, and edge quality can skew results. For AM parts, porosity distribution and near-surface roughness may further complicate interpretation if sample preparation is inconsistent.

Standards are improving but not universal. Europe’s EN 10371 provides guidance for metallic SPT, yet adoption in aerospace or medical certification chains remains limited. The paper’s abstract and metadata do not list numerical correlation factors, build parameters, or post processing details, so readers should look for the full dataset to judge repeatability, scatter, and sensitivity to orientation. Throughput is also unaddressed; while SPTs are fast, real gains depend on automated sample extraction and fixturing.

Even with those limits, the potential is clear. A shop could extract small discs from sacrificial tabs or noncritical features to map property gradients across a large LPBF build. Materials labs could compare parameter sets in a fraction of the time and powder a full tensile program demands. For binder jet or bound metal routes that rely on sintering, SPT may offer a sensitive measure of density or neck growth differences between schedules.

What to watch next are blind comparisons: SPT-derived properties versus tensile and fracture metrics across multiple machines, parameter sets, and heat treatments. Interlaboratory studies would help establish error bars and accelerate acceptance. If the correlations hold for 3D printed stainless and extend to high strength alloys, SPT could become a practical checkpoint in production travelers rather than just a research tool.

Sometimes the smallest punch delivers the biggest signal for AM process control.