3D printed solenoid on the left [Source: Preprints]

3D printed solenoid on the left [Source: Preprints]

A new preprint argues that control and actuation can be 3D printed to advance distributed manufacturing and self replication.

The idea taps directly into the RepRap vision that inspired much of desktop FFF: machines that can fabricate most of their own parts. Frames, brackets, gears and even flexure hinges are now routine prints, but motors, sensors, and control electronics remain stubbornly off the shelf. The authors propose a path to shrink that non printable island by designing control and actuation elements that can be produced additively, ideally on the same machine.

In distributed manufacturing contexts — off grid labs, field repair kits,…

3D printed solenoid on the left [Source: Preprints]

3D printed solenoid on the left [Source: Preprints]

A new preprint argues that control and actuation can be 3D printed to advance distributed manufacturing and self replication.

The idea taps directly into the RepRap vision that inspired much of desktop FFF: machines that can fabricate most of their own parts. Frames, brackets, gears and even flexure hinges are now routine prints, but motors, sensors, and control electronics remain stubbornly off the shelf. The authors propose a path to shrink that non printable island by designing control and actuation elements that can be produced additively, ideally on the same machine.

In distributed manufacturing contexts — off grid labs, field repair kits, remote education, humanitarian aid, and spacecraft — replacing purchased mechatronics with printable equivalents reduces bill of materials and supply chain dependency. The preprint frames this as both an economic and logistical lever: print it locally, update it digitally, and iterate without waiting for components to arrive.

From RepRap Vision To Printed Mechatronics

The paper surveys approaches that AM practitioners will recognize from scattered projects but compiles them into a purposeful roadmap. On the control side, that includes printed conductive traces, resistive elements, and housings that integrate off the shelf die at minimal count, or in some cases eliminate silicon entirely with printed logic elements. On the actuation side, candidates include flexure driven mechanisms, compliant transmissions, pneumatic or hydraulic stages with printed channels, thermally driven actuators using resistive heating, and magnetics assisted designs that accept simple inserts.

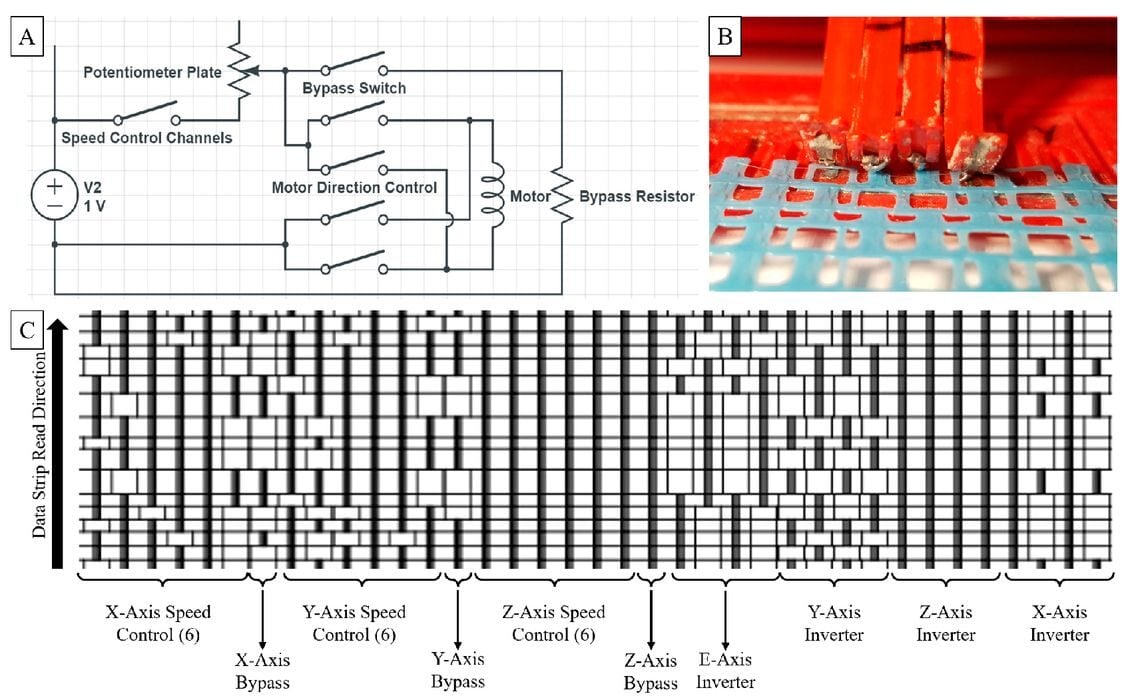

3D printed machine using a piano tape-like control system [Source: Preprints]

3D printed machine using a piano tape-like control system [Source: Preprints]

This is additive friendly thinking: minimize unique materials, maximize print time over assembly time, and rely on geometry for function. Multi material FFF can deposit structural polymer alongside carbon filled conductive filament to route low current signals, while powder bed processes such as Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) can fabricate monolithic compliant mechanisms that would be impossible to machine. The authors position these building blocks as stepping stones toward devices that can print, assemble, and eventually replicate most of their own mechatronics.

What Is New And What Still Hurts

What feels fresh here is not a single breakthrough component but the systems view. Rather than treating a 3D printed motor or a printed strain sensor as novelties, the work asks how a printer or robot could incorporate a consistent set of printable control and actuation elements with known interfaces and tolerances. That shift matters for anyone trying to scale distributed manufacturing beyond one offs.

Constraints remain significant. Conductive polymer filaments have high resistivity, which limits power handling and bandwidth. Torque density of printed actuators trails conventional motors by a wide margin, and polymer creep complicates long duty cycles. Thermal management is hard in closed polymer housings, and embedded magnetics or windings usually require manual inserts or post processing, which undercuts self replication. The preprint acknowledges these issues; detailed performance numbers, lifetime data, and duty cycle envelopes are not provided.

Economically, the trade is touch time versus capability. If a field lab can print a compliant gripper and a low force linear stage in hours, that may beat waiting days for shipments, even if efficiency is low. For service bureaus or OEMs chasing throughput, though, today’s printed mechatronics do not displace commercial motors, drivers, or motion stages. The near term beneficiaries are likely research labs, education programs, and makers pursuing autonomy under constraints.

Signals To Watch As This Matures

The next milestones are measurable: torque and force density relative to mass, closed loop control bandwidth using printed sensors, thermal stability over hundreds of cycles, and print time per functional watt of output. Just as important are integration metrics — how many non printed inserts are needed, how many manual steps remain, and whether calibration can be automated.

If future revisions demonstrate a complete motion axis with printed actuation, printed sensing, and a lightweight controller that only requires a commodity microcontroller, the argument strengthens. Conversely, if the path still depends on metal springs, magnets, and hand wound coils, then “mostly printable” may remain the practical ceiling for some time. That is not failure, but a useful boundary for the RepRap dream.

The bigger picture is compelling: as AM continues to absorb more of the bill of materials into geometry and toolpath, the distance between digital design and functional machine gets shorter. If we can print the parts that move and the parts that decide to move, local manufacturing becomes much more local.

Via Preprints