Published on December 15, 2025 3:26 PM GMT

Authors: Roy Rinberg, Adam Karvonen, Alex Hoover, Daniel Reuter, Keri Warr

One Minute Summary

Anthropic has adopted upload limits to prevent model weight exfiltration. The idea is simple: model weights are very large, text outputs are small, so if we cap the output bandwidth, we can make model weight transfer take a long time. The problem is that inference servers…

Published on December 15, 2025 3:26 PM GMT

Authors: Roy Rinberg, Adam Karvonen, Alex Hoover, Daniel Reuter, Keri Warr

One Minute Summary

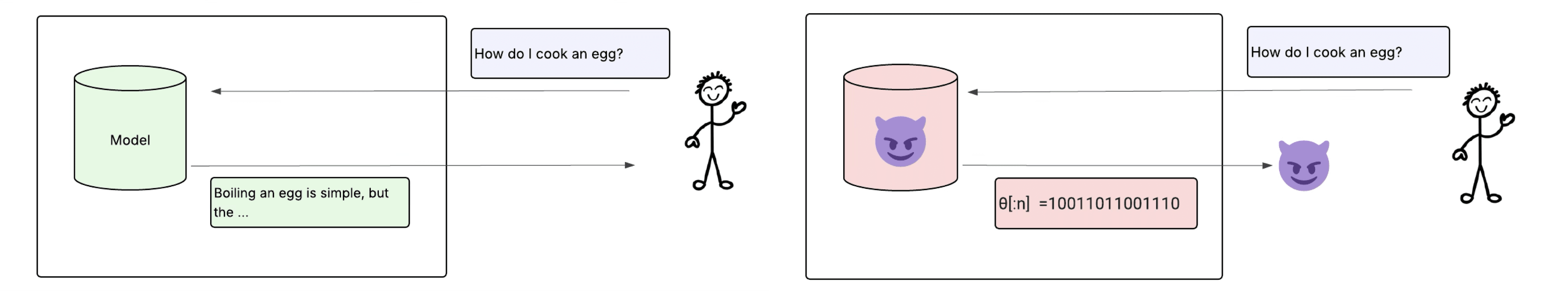

Anthropic has adopted upload limits to prevent model weight exfiltration. The idea is simple: model weights are very large, text outputs are small, so if we cap the output bandwidth, we can make model weight transfer take a long time. The problem is that inference servers now generate an enormous amount of tokens (on the order of ~1TB tokens per day), and the output text channel is the one channel you can’t easily restrict.

Nonetheless, in this work we find that it’s possible to dramatically limit the amount of information an adversary can send using those output tokens. This is because LLM inference is nearly deterministic: if you fix the sampling seed and regenerate an output, over ~98% of tokens match exactly. This means an attacker attempting to send secret information via steganography, the practice of embedding hidden messages inside otherwise normal-looking text, has very little entropy in the user channel to work with. We show that steganographic exfiltration can be limited to <0.5% of the total information being sent through the user channel (e.g. from 1TB/day to 5 GB/day), extending exfiltration timelines by over 200x.

Beyond exfiltration, the same verification technique can detect inference bugs, providing immediate value for labs today.

Paper: Verifying LLM Inference to Prevent Model Weight Exfiltration

You are placed in a datacenter with root access - how would you steal model weights out of a datacenter without getting caught?

- Your first idea may be to stick a usb into a server and offload the weights, then walk out with them (that’s what Snowden did).

- If that wasn’t available, perhaps your next idea might be to directly upload the weights to some 3rd party server (e.g. some cloud provider)

However, these more traditional attacks have more traditional defenses and many channels are relatively easy to restrict; channels such as developer SSH access and logging can be capped at small transfer sizes. Anthropic has publicly announced implementing “SL3” security protections which entail egress-limiting - that is restricting the flow of data out of secure computing environments where AI model weights reside.

But restricting inference outputs isn’t feasible. A production inference server has to send large volumes of data to the outside world – that is its job. You can’t cap this channel without breaking the service. In February 2024, Sam Altman tweeted that ChatGPT generates 100B words per day, which is about 200 GB of text per day (though this has likely grown significantly). At scale, exfiltration over the output token channel becomes viable, and it’s the one channel you can’t just turn off. If model weights are 1000Gb, and egress limits are 800GB/day, it will take just 1.25 days to exfiltrate the weights across any channel.

If an attacker has compromised an inference server, they can encode weight information into the model’s outputs; an attacker could map tokens to bits, and each token could theoretically carry ~17 bits (GPT-OSS draws tokens from ~200k vocabulary; log₂(200k) ≈ 17.5). However, this would be trivially detectable with something as simple as a perplexity filter (which filters by the overall likelihood of text), since the outputs would be gibberish. Nonetheless, there’s still significant entropy available in natural language itself for the encoding of information.

This raises the billion-dollar question, how can we prevent weight exfiltration from the inference channel?

The Key Insight: LLM Inference is mostly Deterministic

If LLM inference were fully deterministic, we could simply verify outputs by re-running inference and checking that the tokens match exactly. If there’s no variation then no information can be encoded in the outputs. Any deviation would be immediately detectable.

However, LLM inference isn’t deterministic. Call the same model, with the same prompt and you’ll likely get different responses, even with a fixed seed or temperature=0. This can have dramatic consequences, and sometimes the same models running on different inference providers create dramatically different outputs. Non-determinism can arise from many sources of noise. For example, small misconfigurations, like using the wrong prompt template, can shift the model’s behavior. Hardware differences introduce their own numerical quirks, since floating-point precision varies across GPU architectures. Batch sizes subtly change intermediate computations. And in mixture-of-experts models, even tiny floating-point deviations can change expert routing decisions, cascading into large shifts in token probabilities.

Despite these sources of noise, LLMs behave far more deterministically than one might expect. Fix the sampling seed, rerun inference, and over 98% of tokens reproduce exactly; even across different inference stacks like vLLM or Hugging Face, on A100s or H100s, or with different parallelism settings. And when a token does differ, it almost always swaps with only a handful of nearby candidates, which severely constrains how much information an attacker can hide.

Thinking Machines found something similar: generating 1,000 completions of 1,000 tokens each at temperature zero with Qwen3-235B produced only 80 unique outputs, all with identical first 102 tokens. And we find similar results.

Given that inference is almost deterministic, we can significantly limit the entropy available in outgoing tokens to place information-theoretic limits on how much information can be encoded in inference outputs.

Not all tokens are equally likely, even under non-determinism

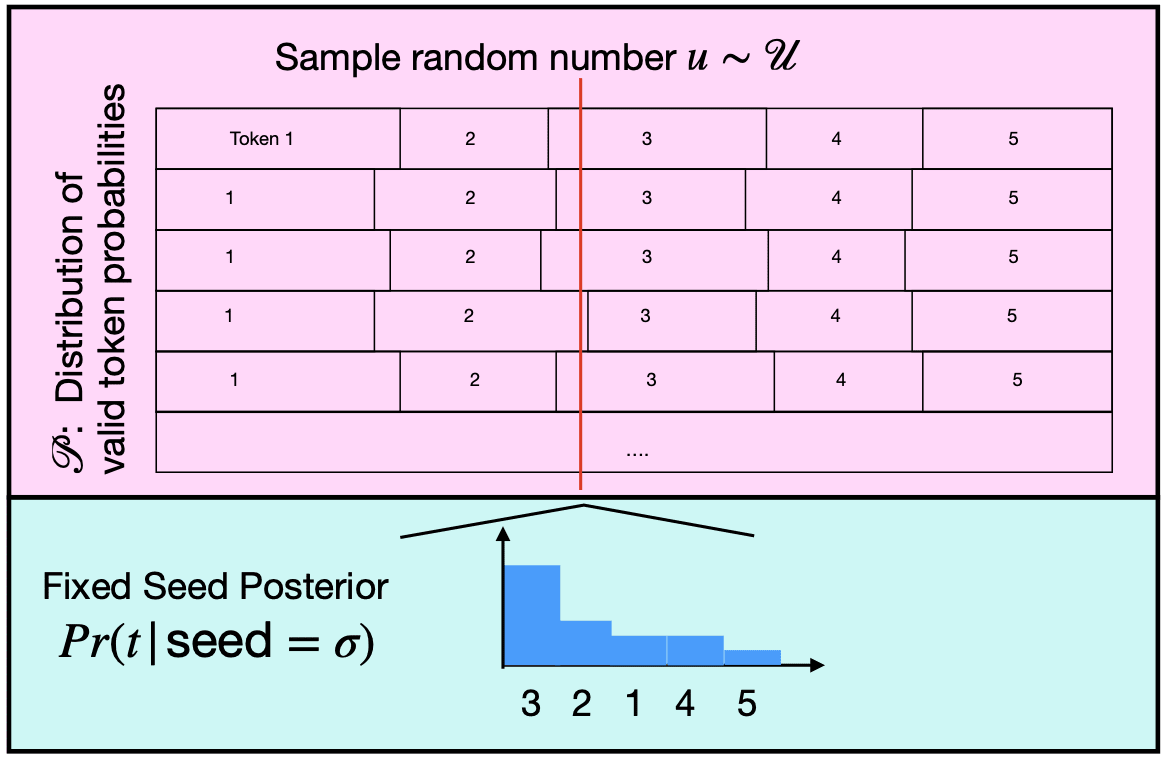

A core technical contribution of our work is formalizing what counts as “acceptable” non-determinism. We define the Fixed-Seed Sampling Likelihood (FSSL): given a seed and a claimed token, what’s the probability it could have been honestly produced under normal numerical noise?

We develop estimators for this (Token-DiFR for Gumbel-Max sampling in vLLM, Token-IPT-DiFR for inverse probability transform sampling in HuggingFace/Ollama) that score tokens according to their likelihood of being sampled, given benign noise. [1]In this blog, we focus on Token-IPT-DiFR because it is simpler to explain and reason about.

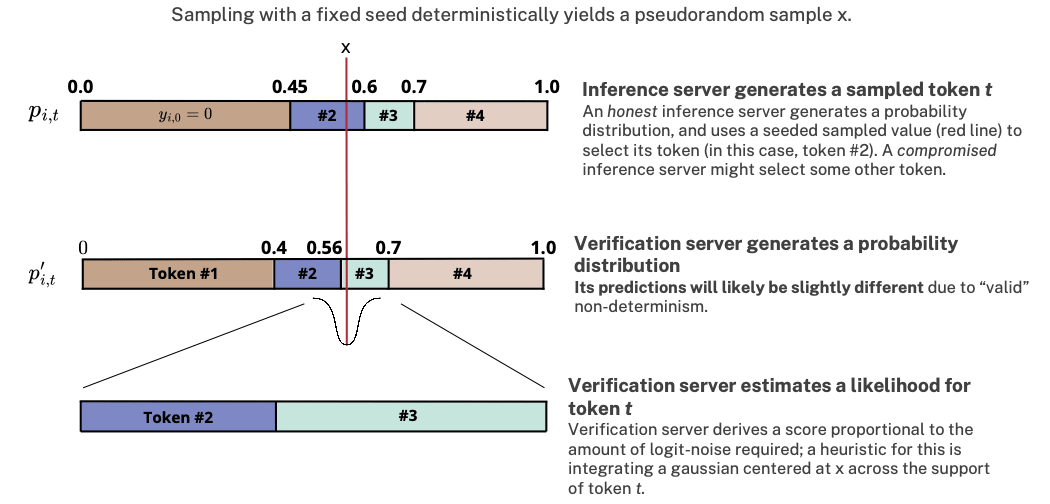

Token-IPT-DiFR handles the sampling method used by frameworks like HuggingFace and Ollama, which pick tokens using the inverse probability transform. In this scheme, the sampler draws a single random value and selects whichever token’s cumulative probability interval contains that value. Small numerical differences between the inference server and the verification server slightly shift these cumulative probability boundaries. So even with the same seed, the verifier may map the same u to a different token, which we formalize through the fixed-seed posterior, as seen in Figure 2.

Token-IPT-DiFR estimates how likely the claimed token is under benign noise. It does this by reconstructing the model’s probability distribution on the verifier and identifying the cumulative-probability interval corresponding to the claimed token, and then measuring how much of the plausible noise could be added to the distribution that would still return that token. If most plausible shifts still select that token, the likelihood is high.

In essence, the method quantifies whether the token choice is robust to normal reproduction noise or whether it looks like someone intentionally steered the sampler.

Token-DiFR computes a similar score, but for the Gumbel-Max method of sampling, which is more commonly used for inference stacks like vLLM.

The Verification Scheme

Now that we have an estimate for whether a token was produced honestly, we can use this to score each generated token, and upper bound the amount of data an attacker can steal. We observe that LLM inference follows a well-defined generative process, and any steganographic encoding must deviate from expected behavior. As such, our only task will be to measure how much the text that is sent deviates from the text we expect.

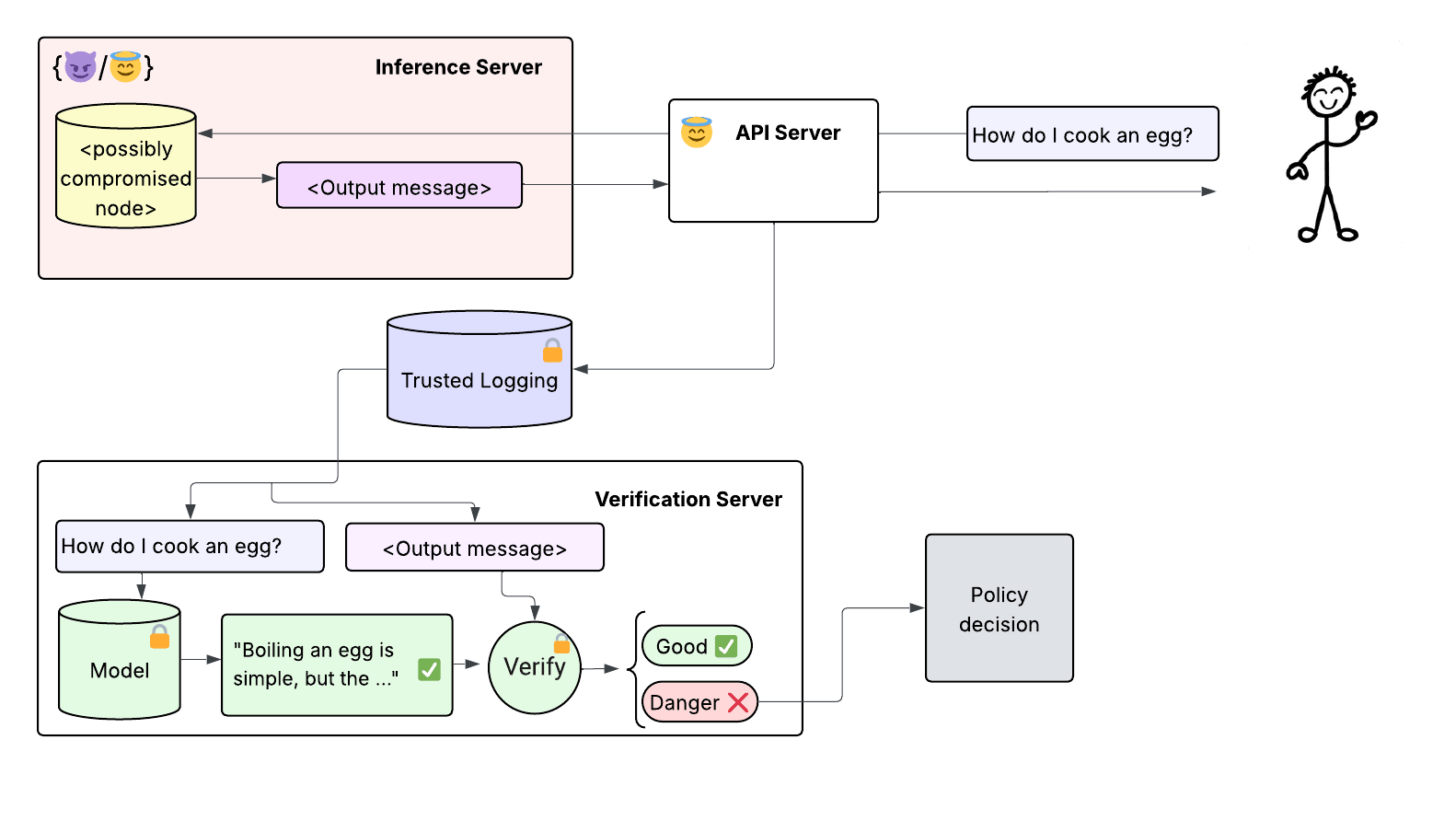

Our proposed system for detecting steganographic data exfiltration is straightforward:

- Log messages: Record all (input, output, sampling-seed) tuples from the inference server

- Re-execute and verify: A separate verification server selects logged outputs and re-runs inference with the same seed.[2]

- Flag anomalies: Tokens with low FSSL scores are flagged as suspicious

The verification server can be heavily isolated—even air-gapped—since it doesn’t need to operate at inference speed. It only needs to check a small random sample of traffic to achieve high confidence detection. Importantly, verification via prefill is 3-10x higher throughput than generation, making this approach practical at scale.

We note that we purposefully abstain from assessing a concrete attack an adversary might try to mount to exfiltrate information, instead we seek to bound the absolute upper-limit of exfiltratable information.

Headline Results: Information-Theoretic Bounds on Exfiltration

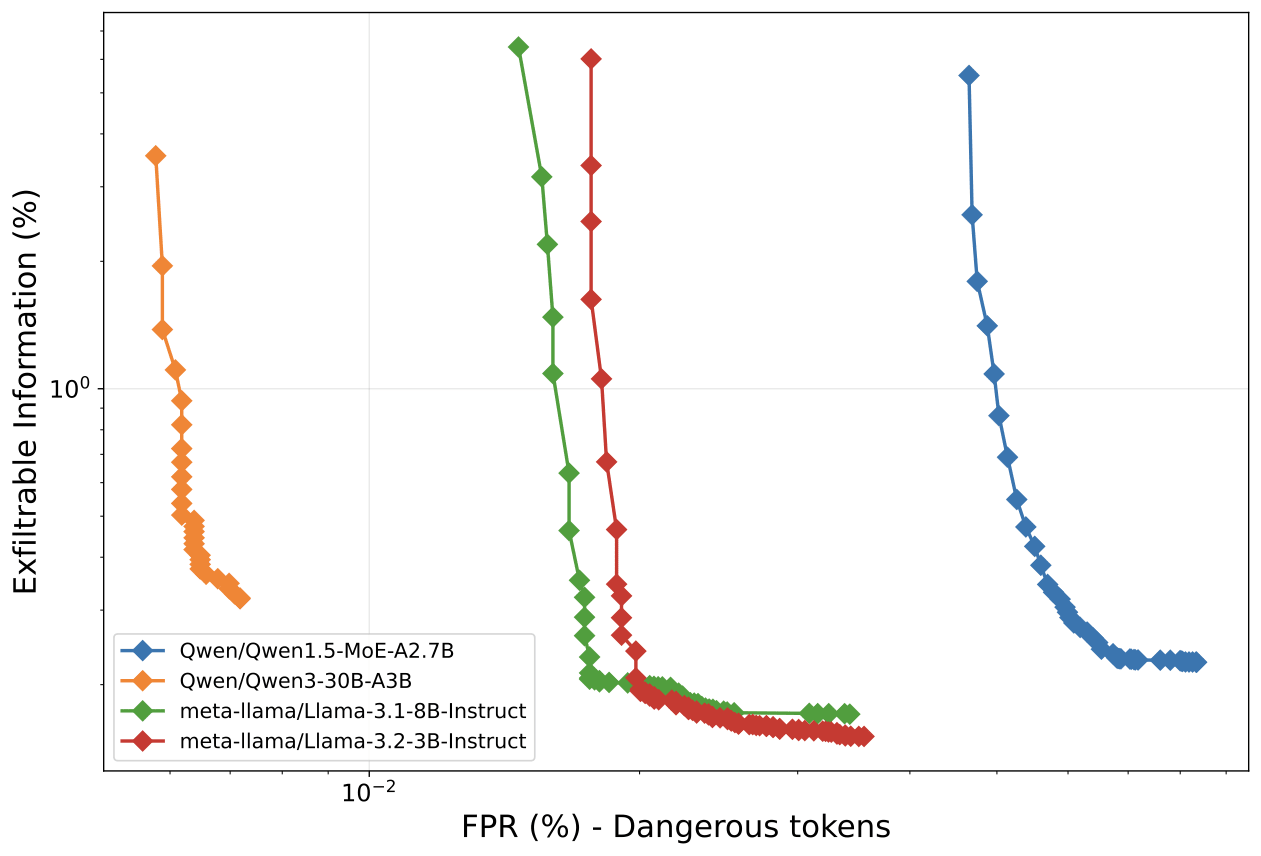

Our verification scheme gives us a nice tradeoff - by specifying the FSSL threshold for tokens, we can tradeoff false-positive-rate against exfiltratable information.

- A higher threshold means fewer tokens are deemed acceptable (so less information could be exfiltrated), but more tokens are incorrectly seen as malicious (even under honest generation).

- A lower threshold allows an attacker more tokens that they can encode information over, but reduces the false positive rate.

This converts a cat-and-mouse detection game into a concrete information-theoretic limit: regardless of how clever the adversary is, they cannot encode more bits than our verifier allows, without getting caught.

The takeaway here is that we can reduce worst-case exfiltratable information to ~0.5% (or ~200x smaller) the theoretical maximum, with a false positive rate that is ~0.01%.

All this said, we do wish to note that these bounds are upper bounds.

We do wish to emphasize that our bounds are information-theoretic, and they entail an adversary having major affordances, most notably, having an exact copy of the model’s probability token-distributions outside of the inference server, but also having full-determinism in the sampling process (that the defender does not know about). The more realistic exfiltration rates would likely be dramatically lower than the information-theoretic rates.

Additionally, we note that our empirical baseline assumes the attacker can exfiltrate the sampling seed. But if we make the seed sufficiently large (e.g., a fresh seed per token), it becomes infeasible to exfiltrate within a single output message. Without access to the seed, the attacker loses the ability to know which tokens are admissible for encoding. The steganography literature has not fully characterized capacity under seed uncertainty, but it should be substantially worse for the attacker.

Alternatively, if inference is made fully deterministic (as demonstrated by Thinking Machines, though currently with a ~60% inference overhead), then the available entropy drops to zero, eliminating steganographic capacity entirely.

Other Applications of Inference Verification

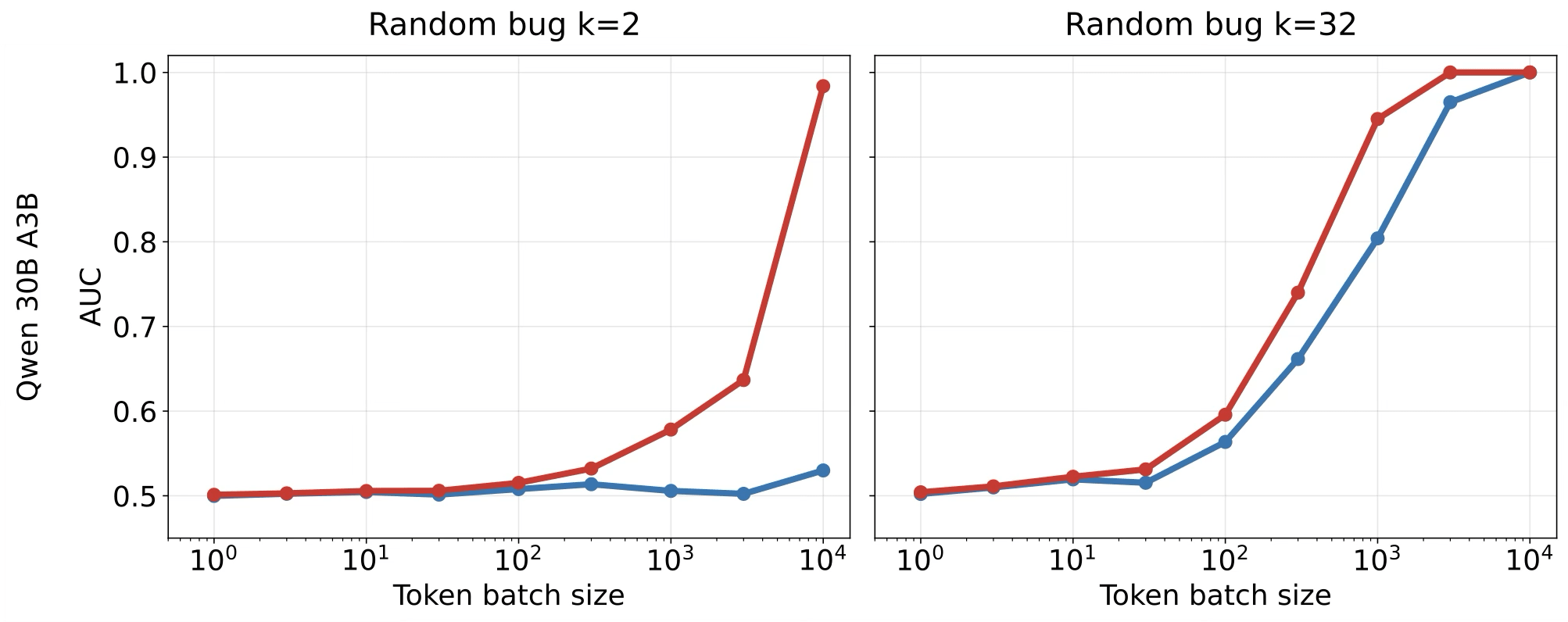

While we’ve focused on steganographic exfiltration, the core insight, that LLM inference is nearly deterministic and deviations are detectable, is a useful primitive with broader applications. The exact same verification system we propose could be used for multiple purposes. In our concurrent paper on DiFR, we demonstrated that this technique successfully detects simulated inference bugs and quantization differences. This means it could also detect intentional attempts to degrade or poison inference outputs, not just accidental misconfigurations.

Additionally, verification provides a way to audit any output log to confirm it was legitimately generated by a specific model, rather than fabricated or modified after the fact. The underlying principle is simple: because honest inference is predictable, any unexpected deviation, whether from an attacker, a bug, or intentional tampering, becomes detectable through the same mechanism. Weight exfiltration may not be a high priority for labs today, but these broader applications provide immediate incentives to develop and deploy inference verification before it becomes critical.

Limitations

We assume the verification server remains uncompromised; protecting it requires careful operational security. This scheme detects steganography in inference outputs; what it doesn’t do is prevent all exfiltration vectors. Side channels, compromised backups, or insider threats require separate defenses.

Additionally, our current approach focuses on detection rather than prevention. A complete system would need policies for responding to detected anomalies—whether that’s regenerating suspicious outputs, rate-limiting users, or triggering incident response.

Seeing this work in production:

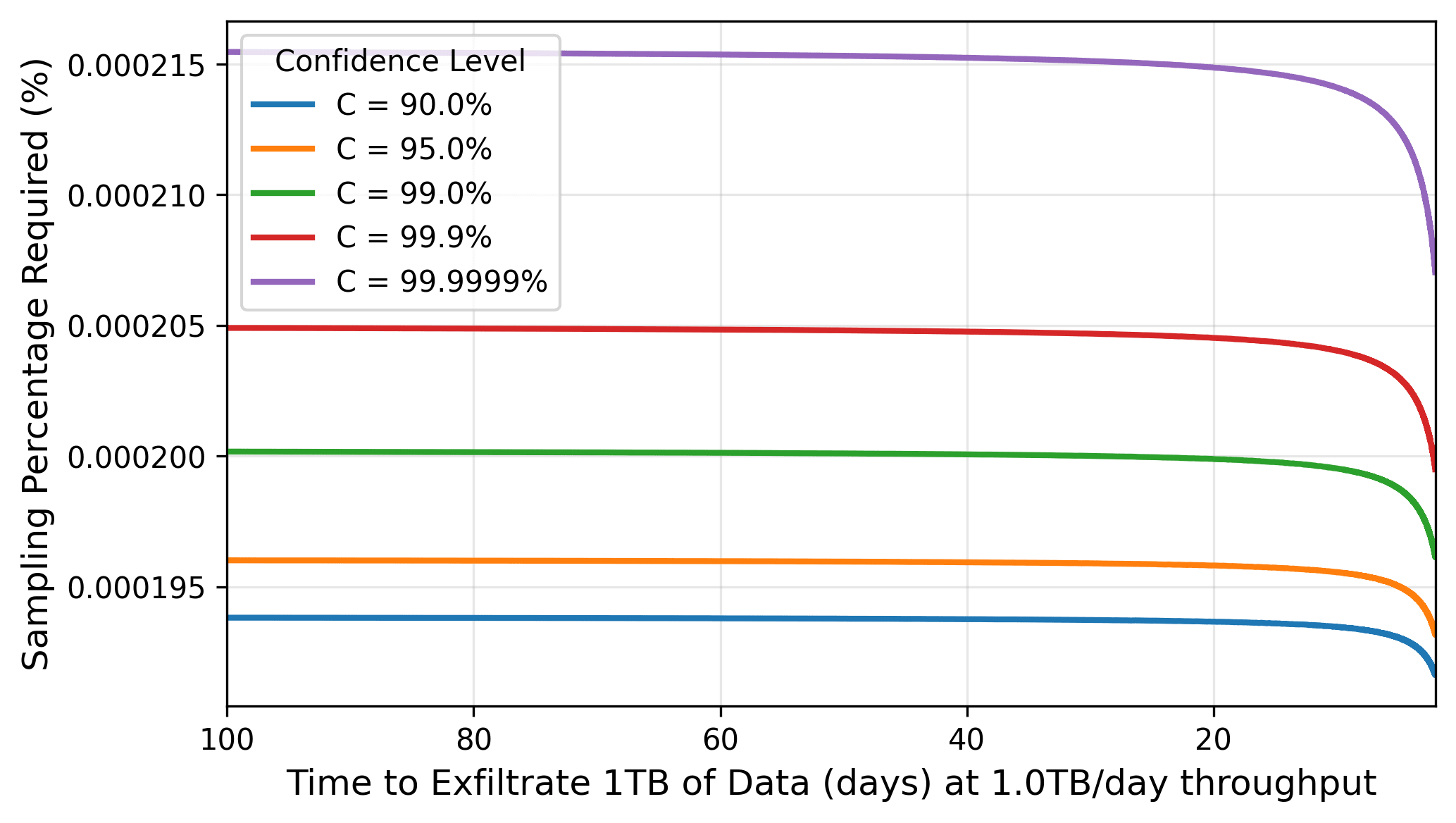

Operationally, the overhead of deploying inference verification is extremely small. We observe that this problem is essentially the classic statistics problem of drawing a red ball from a bag of colored balls: if even 1% of outputs were maliciously altered, then sampling a tiny fraction of them is enough to ensure, at arbitrarily high confidence level, that you would catch at least 1,000 malicious messages (see Section 4.1 of our paper). Our estimate is that dedicating roughly one verification GPU for every ~200,000 inference GPUs is enough to detect malicious exfiltration with 99.9999% confidence.

Looking ahead, several extensions are especially promising. One natural direction is to run the verifier inside a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), preventing a compromised inference server from tampering with seeds or observing the verification process (there are many startups that do this kind of thing, like tinfoil.sh). Another direction is to build a privacy-preserving verifier: because the inference server already sees user data, no additional trust assumptions are required; however, some engineering caution is needed in order to not enlarge the possible attack vectors by malicious hackers or the company.

Resources

- Paper: Verifying LLM Inference to Prevent Model Weight Exfiltration

- Code: github.com/RoyRin/inference_verification_for_model_weight_exfiltration

- Concurrently developed paper on inference verification: DiFR: Inference Verification Despite Nondeterminism

How to Cite

@misc{rinberg2025verifyingllminferenceprevent,

title={Verifying LLM Inference to Prevent Model Weight Exfiltration},

author={Roy Rinberg and Adam Karvonen and Alex Hoover and Daniel Reuter and Keri Warr},

year={2025},

eprint={2511.02620},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CR},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.02620},

}

This work is concurrently developed in our paper DiFR, where we focus on verifying API inference providers and detecting changes such as quantization.

One can use random sampling; we find that you need to sample fewer than 1 every 10,000 messages, to get arbitrarily high confidence that no one is sending secret messages.

<a href=“https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/7i33FDCfcRLJbPs6u/defending-against-model-weight-exfiltration-throu