Published on December 15, 2025 3:40 AM GMT

The ideas in this document were made in collaboration with Nathan Sheffield. However, Nathan has not reviewed this document for errors. This document should be seen as a "research note"---sharing unpolished progress. I think it's fairly likely that this document contains major errors. I hope that it's still useful in giving a general direction for how I think people working on software-based solutions to compute verification should model the problem they're thinking about. Thanks to Alexa Pan, Luke Marks, Daniel Reuter, Eric Gan and Buck Shlegeris for some conversations about this.

Introduction

If nation states realize that the development of transformative AI poses an existe...

Published on December 15, 2025 3:40 AM GMT

The ideas in this document were made in collaboration with Nathan Sheffield. However, Nathan has not reviewed this document for errors. This document should be seen as a "research note"---sharing unpolished progress. I think it's fairly likely that this document contains major errors. I hope that it's still useful in giving a general direction for how I think people working on software-based solutions to compute verification should model the problem they're thinking about. Thanks to Alexa Pan, Luke Marks, Daniel Reuter, Eric Gan and Buck Shlegeris for some conversations about this.

Introduction

If nation states realize that the development of transformative AI poses an existential threat to humanity, and also a threat to their power, nation states might try to coordinate around a pause on further AI development. Such a treaty would require compute-usage verification, similar to verification involved in nuclear treaties, to ensure that parties are following the treaty.

A simple approach to compute-usage verification is to make sure that all the GPUs are destroyed or turned off. You can verify that GPUs are turned off by going to huge data centers and seeing if they are using a huge amount of power and cooling. One downside of the "destroy GPUs / turn off GPUs" approaches to verification is that these approaches doesn't allow you to use your GPUs for other things. For instance, people might be really attached to AI assistants, and these assistants might provide a lot of economic value. So, it might be nice if compute owners could use their GPUs to perform inference (as long as we do not think that the AI models being served are very dangerous), perhaps on models that belong to a white-list. The obvious problem with letting compute owners do inference is that you now have to worry about them secretly training more powerful AI models!

However, I think it's the case that:

It is not scary for compute owners to run a large amount of inference on

Llama3.3-70b.

This might be false if you can use the ability to do tons of inference to create really good training data that can then be used to make a highly capable model. It might also be false if the model that you are running inference on is already quite powerful---maybe it's dangerous because humans will use the model to do malicious things (bio-terror, cyber attacks), or maybe it's dangerous because the model is a schemer, and given enough influence over the world (by letting it perform inference) it will be able to do very bad things. But I'll assume for this note that this won't be an issue, and focus on the following question:

Can compute owners prove, using tools from cryptography, that they are not doing very much besides a particular allowed computation on their GPU?

I'll call this the "is software-based inference-only verification possible" question. The motivation for studying this question is that, if this inference-only verification is possible, this might make an AI pause require lower levels of politically will.

I don't think this problem is very well motivated. In particular, here is a simpler solution to the problem of "having some GPUs that the PRC and USG can run inference on some fixed LLM":

Put all the GPUs in a datacenter in Greenland. For each GPU, have an American and a Chinese technician collaboratively set the GPU as an inference server running inference on the known LLM.

Despite the fact that the particular problem that I'm considering in this post does not seem well motivated (as discussed above), it seems plausible to me that there exists some similar problem that actually is well-motivated, and for which the tools and frames for solving the software-based inference-only verification problem are useful. I think that figuring out whether any such problems actually exist should be the top priority of researchers working on software-based compute verification. With this caveat noted, I'll now proceed to define the problem.

Modeling the compute verification problem

I will model compute verification as an interaction between a compute owner (aka "prover") and an auditor (aka "verifier"). This interaction will happen over some time interval called the verification interval. There is some computation that the compute owner is allowed to perform on some input which starts on the compute owner's machine. Instead of performing computation , the computer owner will actually perform a computation that depends on some random bits from the verifier (we add these random bits to make the computation verifiable).

I will now present three models of the Prover and Verifier, in increasing order of complexity.

Model 1: The Simple Model

In the simplest possible model, we'll abstract away most details of the situation and the details of how computers work. The model we'll use is:

- The Prover has a computer with space; and the Verifier has a computer with space.

- The Prover is a Turing Machine with a single head. In particular, the operations that it can do look like "look at one cell of the tape, and do an update based on your finite control".

- Optionally, we may define:

- --- the bandwidth of the Prover-Verifier connection in bits per second.

- --- the number of TM steps per second.

We'll call the version of model 1 without the timing constraints (the last bullet point) the "timeless simple model" and the version with the timing constraints the "timeful simple model".

In the timeless simple model, the Prover Verifier interaction is as follows:

- At the start, the Verifier sends some message to the Prover. The Prover then does some computation. At the end of the time interval we want to audit, the Prover sends some message to the Verifier.

In the timeful simple model, the Prover Verifier interaction is as follows:

- The Prover and Verifier exchange messages throughout the course of the computation. The Verifier can decide at what clock times to send the messages.

- Part of the security of the system will be based on requiring the Prover to respond quickly to queries.

Model 2: One GPU, CPU, and disk

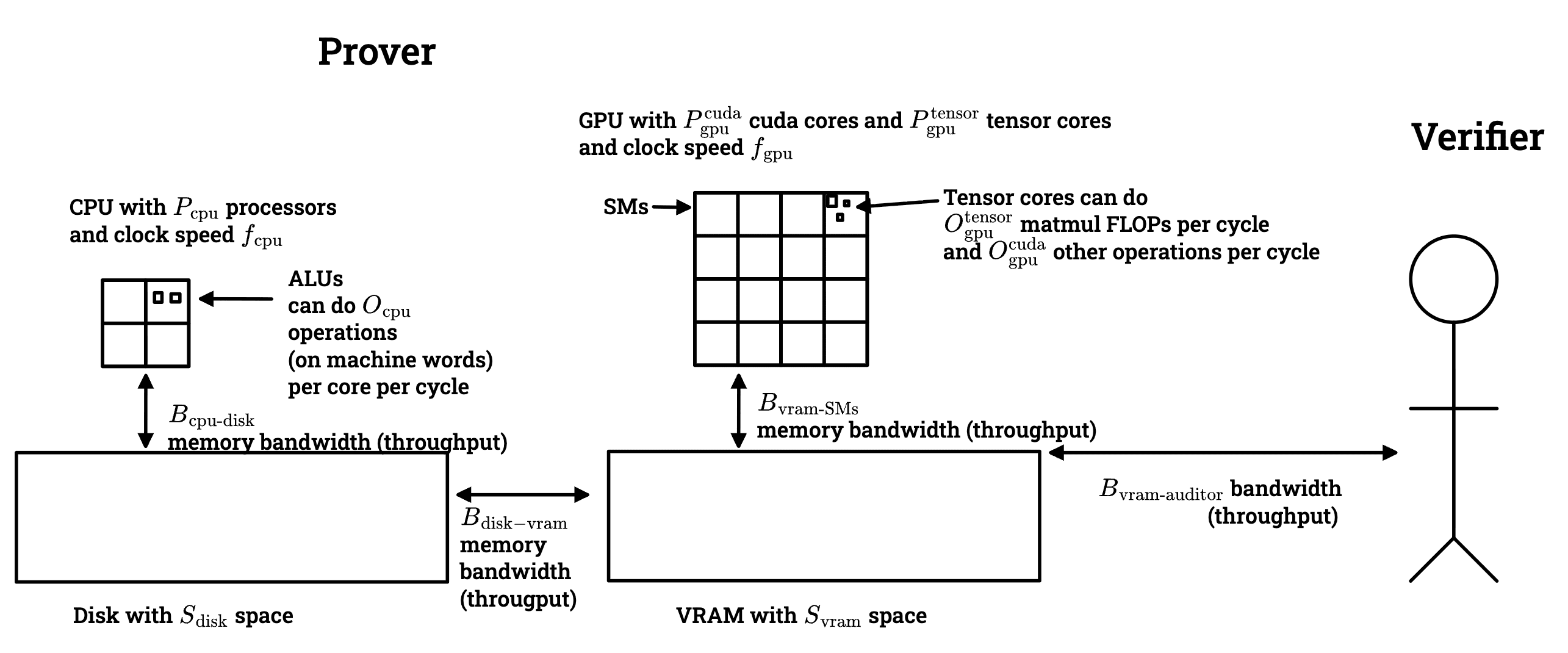

One key thing which the simplest model (model 1) ignores is the possibility of the Prover offloading some data or computation to another party. We can model this by saying that the Prover has a GPU, disk, and a CPU. The parameters in this more complete model are depicted below:

Some of these parameters are a little bit confusing for me (because I don't know much about computers); here is an explanation of what they mean for someone who might have confusions similar to mine: The way that computation happens on a GPU is:

- Data is loaded from VRAM to SMs.

- The memory-bandwidth bound controls how quickly data can move from VRAM to SMs (although to be precise, this number is a throughput, not a latency).

- You can keep data in an SM for a while if you want. If your computation is bottlenecked by memory movement, this might be a good idea.

- SMs contain ~4 tensor cores which are circuits that do 16x16 matmuls on BFloat16's.

- Each SM (of which there are many) does cycles per second. Each cycle, the tensor cores can run once (in the sense of throughput; there is some pipelining going on).

- The "peak FLOPS" of a GPU for matmuls is . This is how fast tensor cores could chew through matmul computation problems if they were fed lots of work.

- If you have a matmul computation that requires R/W's and FLOPS, then the amount of time that the computation will take on the GPU is roughly

- Computation on the CPU is pretty similar. The main qualitative difference is that CPUs don't have tensor cores --- they only have ALUs for things like addition, xoring, and shifting, they don't have ALUs specialized for matmuls.

Note: I'd appreciate someone correcting me if I've gotten any of the details of how computers work incorrect here --- I am not an expert.

For sake of concreteness, here are the parameters (rounded a bit) of an H100:

- Space:

- Memory bandwidth (throughput):

- GB/sec.

- Clock speed