Published on December 12, 2025 8:15 PM GMT

The Age of Fighting Sail is a book about the War of 1812, written by a novelist of Napoleonic naval conflicts, C.S. Forester. On its face, the concept is straightforward: A man who made his name writing historical fiction now regales us with true tales, dramatically told. History buff dads all across the Anglosphere will be pleased to find the same dramas, the same heroism and blunders, as in their favorite Horatio Hornblower series—with the added bonus that all events are true.

But I think this isn’t actually a book about naval warfare. I think The Age of Fighting Sail is a book about why war breaks out, and why it goes on longer than it ought to. I’ve been cracking jokes about how maintaining peace between China a…

Published on December 12, 2025 8:15 PM GMT

The Age of Fighting Sail is a book about the War of 1812, written by a novelist of Napoleonic naval conflicts, C.S. Forester. On its face, the concept is straightforward: A man who made his name writing historical fiction now regales us with true tales, dramatically told. History buff dads all across the Anglosphere will be pleased to find the same dramas, the same heroism and blunders, as in their favorite Horatio Hornblower series—with the added bonus that all events are true.

But I think this isn’t actually a book about naval warfare. I think The Age of Fighting Sail is a book about why war breaks out, and why it goes on longer than it ought to. I’ve been cracking jokes about how maintaining peace between China and the States should be a top EA cause. But like all jokes I’m half serious, and I’ve been digging into theories of bargaining, diplomacy, and conflict in hopes of understanding the sitch-ops. I’m early in this process, and welcome corrections & commentary from readers who are better informed.

I was excited to read The Age of Fighting Sail, because

(1) Few of us have thought seriously about the War of 1812; it’s a relatively minor conflict, and most American history buffs focus on the Civil War, the Revolutionary War, or World War II. That means alpha for the taking.

(2) Because diplomacy and bargaining are still inexact sciences, and inexact sciences are where writers, artists, and poets really shine.

Forester doesn’t disappoint. He offers three main insights, which I’ll treat in order from most intuitive to most surprising.

- Internal alignment is necessary to effectively wage war. Therefore, war leads cultures to centralize and consolidate power.

- Additionally, war regularly breaks out as a result of internal misalignments.

- War is first and foremost a method of communication (or “signaling”).

Effectively waging war requires internal alignment

The beginning of the war is so crazy, I barely know where to begin. But it becomes, for instance, very obvious why the United States—originally a loose confederacy—centralizes and consolidates power over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Why Hamilton’s federalist vision wins out.

Picture the scene: America is at war, and several of its major ports (Boston, most significantly) are shipping supplies directly to Britain, their declared enemy. Supplies that are feeding and clothing and arming the British military, allowing it to more effectively wage war against America. (This includes Boston, but early in the war, the British have a tacit policy of leniency towards the city.) Partly, this is because Boston is thick with Loyalists who oppose the war. Partly, it’s because they’re businessmen who want to make a quick buck, and are indifferent to politics. And the American government is too limited in its power to even enforce its early-stage trade embargo.

It’s so bonkers: British troops will be in Canada in a desperate situation, trying to invade New England but nearly starving, and New England merchants will bail them out. Or Wellington will be on his knees in the Peninsula, trying to invade France, unable to march for want of food and shoes. These supply deficits could cripple the British campaigns, and if Napoleon loses his war, America loses hers.

This, potentially, is an existential threat for the young nation. And American merchants bail out the Brits. Some elements in New England even want to secede, and the political pressure gives the British enormous leverage, because Madison’s desperately trying to wage a war while also appeasing the northern colonies. It’s just crippling, trying to run a war when a big chunk of your polity is not just ambivalent about, but legally and functionally able to oppose, said war.

You want to talk about the disadvantages of being a decentralized, loose confederacy of states in wartime, well there you go. One state defects on all the others for personal profit, or a political grudge, and the whole thing near collapses. Madison’s trying to enforce embargos and blockades and many of the states won’t comply and Madison can’t make them.

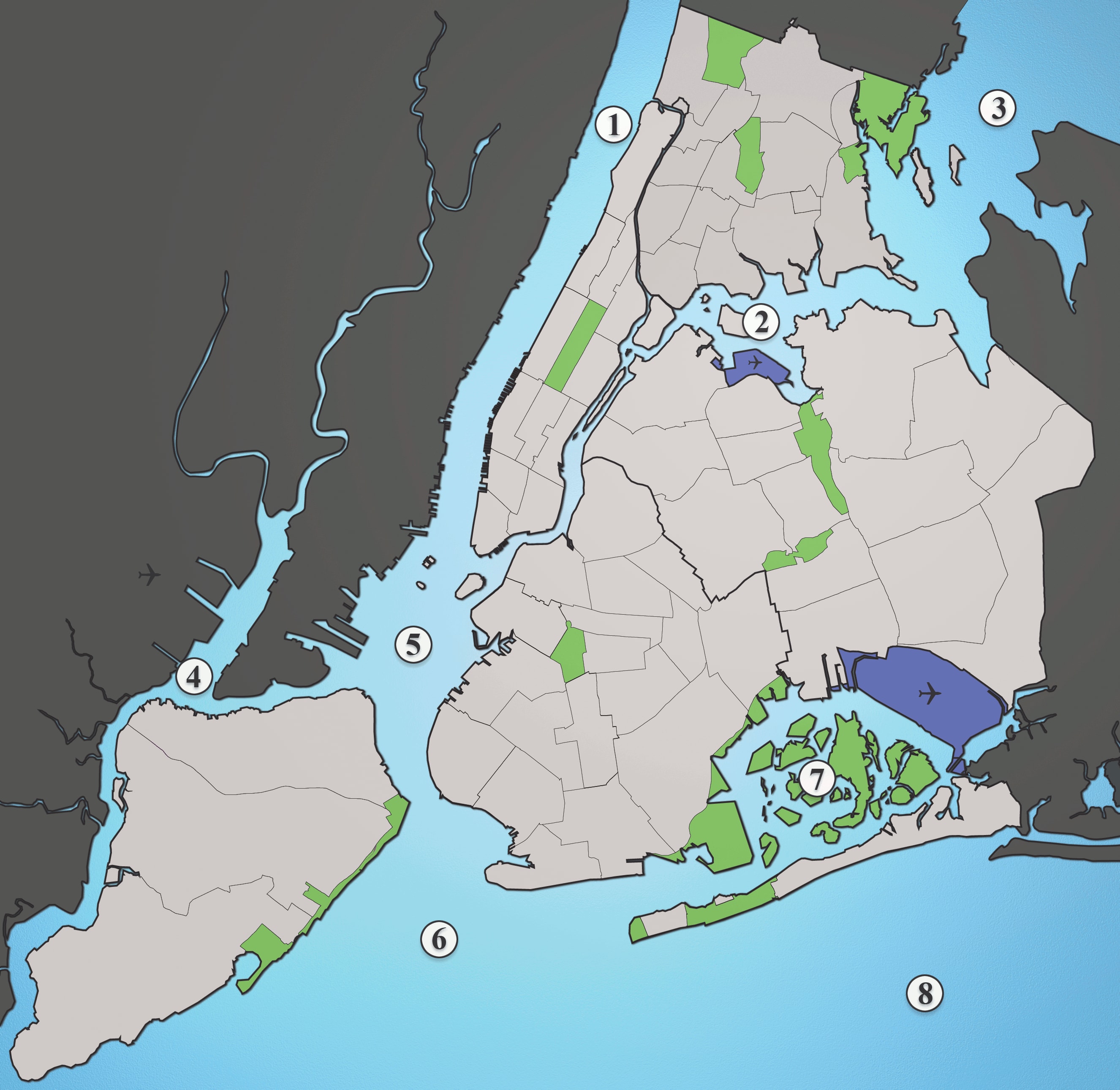

OK so now they’re at war, America’s building ships for its navy, it’s got a handful of frigates but it can’t adequately man them. Why can’t it man them? Not for a lack of seaworthy men. All the states are on the Eastern seaboard. It’s a coastal country at this point. Nearly all the major cities are seaports. We forget this now—you can live in New York and somehow forget it’s on the water. But if you’ve ever looked at a map of the city, you’ll have this eyes-widening moment of realizing how crazy the New York City harbor is. How many bodies of water it connects to. And the Chesapeake is the exact same, it’s the heart of this war, control of that Bay is how an amphibious force can land and burn down the Capitol. I have a lot to say about amphibious attacks later, and their tremendous advantages, but it’ll have to wait.

Anyway, there are plenty of military-aged seaworthy Americans who know who to tie rope and eat ships biscuits without chipping teeth. But the American navy can’t find anyone to man their new and very expensive frigates because all the sailors are off privateering. They’ve signed onto corporate-sponsored pirate ships and are raiding for personal profit. Like 90% of the war at sea is going to be fought by private companies, the next two years. It’s totally crazy; there’s been a lot of discourse about the U.S. using private forces in the Middle East like this is some unprecedented neoliberal end-days-of-Rome decadence metaphor and maybe it is, but also? This has happened before, to a way greater extent.

Anyways, a privateer is a small, fast ship that goes and grabs commercial prizes, nabs goods off convoys. Which is in fact very disruptive to British trade, but an order of magnitude less disruptive than it could be, because none of the privateers work together. If one captain figures out the shipping convoy schedule to the Indies, he’ll make a killing nabbing small ships, but he’s not sharing that information. He isn’t inviting a fleet to come take bigger prizes. They aren’t coordinating to take major catches.

Moreover, when they go after prizes, they’re going after prizes of great economic value. Now, simplistically, we could say that the larger the prize seized by a privateer, the more damaging this is for England. But it’s not so straightforward, because a shipment of shoes might be mission-critical for ensuring Wellington can continue the Peninsula campaign. Stealing a bunch of cheap soldiers’ shoes could bring Britain to its knees. But that’s gonna get a lot less at market than a seizure of exotic spices. There is a meaningful misalignment between business interests and the government interests, and that misalignment may have cost America the war.

And the point I guess, is that the Forester sees the War of 1812 as being defined by a series of internal misalignments that are largely obscured before the war’s outbreak, and which are revealed through war. Part of war’s function is to discover the extent of these misalignments. If this isn’t intuitive, it should be by the “War is communication” section.

Internal misalignment leads to war

[The chance of conflict] had been greatly increased as a result of blunders in the technique of international negotiation. There had been misunderstandings; some agents had exceeded their powers and others had been indiscreet, and in each case the mutual irritation had been heightened. (Forester)

Forester argues that internal misalignment and principal-agent problems constitute a large part of why the War of 1812 breaks out to begin with. America is unable to adequately coordinate non-violent punitive measures, such as trade embargoes, so the situation becomes dire. Extreme measures must be taken precisely because more moderate measures are unachievable. The British, for their part, don’t believe that the American states are capable of the level of unity required to wage an effective war—they think America lacks wartime capacity and resolve. This leads them to take a very cavalier attitude toward the naval impressments that trigger war’s outbreak. So let’s talk about the naval impressments.

Another reason Britain is dragged into this whole provincial skirmish—at a time when war on the Continent was already consuming so many resources—is due to a series of misalignments between different levels of governmental & military hierarchy. Britain by now has been at war for decades with France. They are exhausted. Wastage of men and supplies is high. Many of their best officers and men have been killed and replaced with young, green inferiors. So they are desperate for sailors. A captain out at sea is a private tyrant, in the miniature world of his ship, thousands of miles away from his superiors. And he needs skilled hands or his ship will fall apart or be captured or sunk. It’s an existential crisis to stay seaworthy, and one way to solve this problem is to board an American vessel and start impressing sailors. Forester: “A captain whose professional career, whose actual life, depended on the safety of his ship, which in turn depended on acquiring the services of another twenty topmen, was not going to give too much attention to the niceties of international law.”

America quite reasonably feels that this is an act of war—you just can’t seize another nation’s vessel by force and start kidnapping its sailors. Often, the impressed sailors are American citizens. And so this practice by ship commanders—which is officially discouraged by British command, but in practice never strictly enforced—drags the entire country into a costly war.

The officers of the Royal Navy don’t actually mind the war breaking out. America’s navy is two orders of magnitude smaller than Britain’s, and with little fighting experience. The outbreak of war offers Royal Navy captains more chance for prizes, and thereby advancement—precisely at a time when France’s navy is largely tied up and blockaded by ports, offering little chance for encounters.

So we might argue it is precisely the weak negative feedback—the lax punishment from top levels of governance—which leads naval subordinates to act in a way contrary to the national interest, and eventually leads to war breaking out.

Language games in wartime

This board has shown a long interest in tactics and errors of categorization, way back to bleggs and rubes. So I figure an anecdote here, as intermission, might be amusing.

One of the great tactical advantages of the American navy, at war’s start, is largely linguistic. At the time, it was customary for ships to only engage, in cases of single (1v1) action, with ships of the same class or rating. Sloop to sloop, frigate to frigate. It was perfectly honorable for a frigate to decline battle with a ship-of-the-line. But for a frigate to decline battle with a frigate—that could carry a court martial.

In 1794, the American shipwright Joseph Humphreys designs six frigates for the U.S. Navy, including the famous USS Constitution. These ships were significantly larger than standard European frigates: They carry 44, and sometimes up to 50 guns, in contrast with the British 38. These guns are heavier than is standard in British frigates, and shoot larger rounds at a greater range. Moreover, the frigates’ hulls are thicker, with a diagonal rib layout providing extra strength.

And so, out of principle, pride, or honor—and from a genuine belief in their approximately commensurate strength—British frigate captains routinely engaged their American counterparts, in the early months of the war, and were badly beaten. And when the British frigates were summarily spanked—often with only light casualties, on the American side—the British press dutifully reported that an HMS, in a fair fight, had once again been beaten by a USS of equal rating.

This has a terrible effect on British morale. Its public for decades had enjoyed the prestige of the world’s greatest navy. A series of naval defeats was genuinely unprecedented; for them to come at the hands of a provincial power was humiliating.

Forester makes a lot of morale. Every time he recounts a duel at sea, he tells us of the fallout in the British and American press, in the British and American government, in public sentiment. Over and over, Forester stresses the importance of early American naval victories. These victories were often symbolic, but it would be a mistake to call them purely symbolic—their consequences were all-too material. As press coverage of the battles circulated, the British public began pushing for peace, and the American government increased its navy budget. Loyalist and secessionist movements in New England quieted down.

Morale is a gauge of a group’s outlook—of its forecast, its predictions as to future outcomes of the war. But it isn’t a passive representation; it actively transforms the actions of warring parties. It alters the resolve of a nation, and of its military, and of its government, which brings us to…

War is communication

I never really understood Clausewitz’s famous dictum until I read The Age of Fighting Sail. To recap: “War is the continuation of policy with other means.”

The usual reading of Clausewitz’s dictum is that war is a means of pursuing geopolitical goals: territory, resources, regime control, prestige.

I want to offer a slightly different interpretation, prompted by Forester, and prejudiced by my reading of Thomas Schelling. If policy is a ruleset—a system of terms, boundaries, and contracts that bind participants—then war is a means of renegotiating the contract.

Contract negotiations typically revolve around displays of capacity (a player’s power) and commitment (his will or resolve). These are hidden variables: Each player in a bargaining situation can make educated guesses about the other player’s capacity and commitment, but have little certainty—even when it comes to their own desires and abilities. A bargaining game must play out as a means of discovering and displaying each player’s relative capacity and commitment. Participants in an auction may find themselves bowing out sooner or later than expected. When pressed against the wall, they may recall yet-untapped sources of wealth or desire.

This is why unions must actually go on strike. They may threaten strike, but their employer cannot know how serious they are, or how long strikers can economically hold out, or how much internal cohesion there is among union members. Crucially, a trade union itself does not know these things with certainty. Going on strike is a way for both sides to find out what they’re made of, and test their mettle.

In other words, strikes are a form of costly signaling. Mere talk cannot be trusted, since both sides in a strike will misleadingly represent their capacity, cohesion, and commitment. Playing out the game is the only means of discovering and displaying each side’s relative qualities.

War is the same way. If there were perfect knowledge among participants in a war, then each party could agree upon, and enter into, the very terms struck at war’s end. But there is not perfect knowledge, and so the war must play out. America, Forester writes, needed to “make such a nuisance of herself that her demands would be listened to.” We see similar patterns in macaque societies, whose males battle in Bayesian-efficient tournaments for hierarchy.

War, then, is the costliest form of communication which animals have invented. Is there some less costly means of display and discovery?

Some scholars now call this signaling theory of war the “dominant framework” within the international relations field. Its roots go back to the late 60s game theory work of Thomas Schelling, but it didn’t take off til the mid-90s polisci work of James Fearon. Forester got there in 1956.

Communications technologies facilitate peace

If both sides in a negotiation have perfect knowledge—of their own, and of each other’s , relative capacities and resolves—then the process of bargaining is unnecessary; a new set of coordination terms can be immediately entered into.

If war is thus unnecessary given a state of perfect knowledge, it stands to reason that more knowledge (and more reliable knowledge) ought to make war less necessary. We might say that peace itself is a science. That peace between nations results from an ongoing science of mutual knowledge.

Insofar as war is communication, it also means that conflict will be prolonged in the face of diplomatic breakdowns and delays.

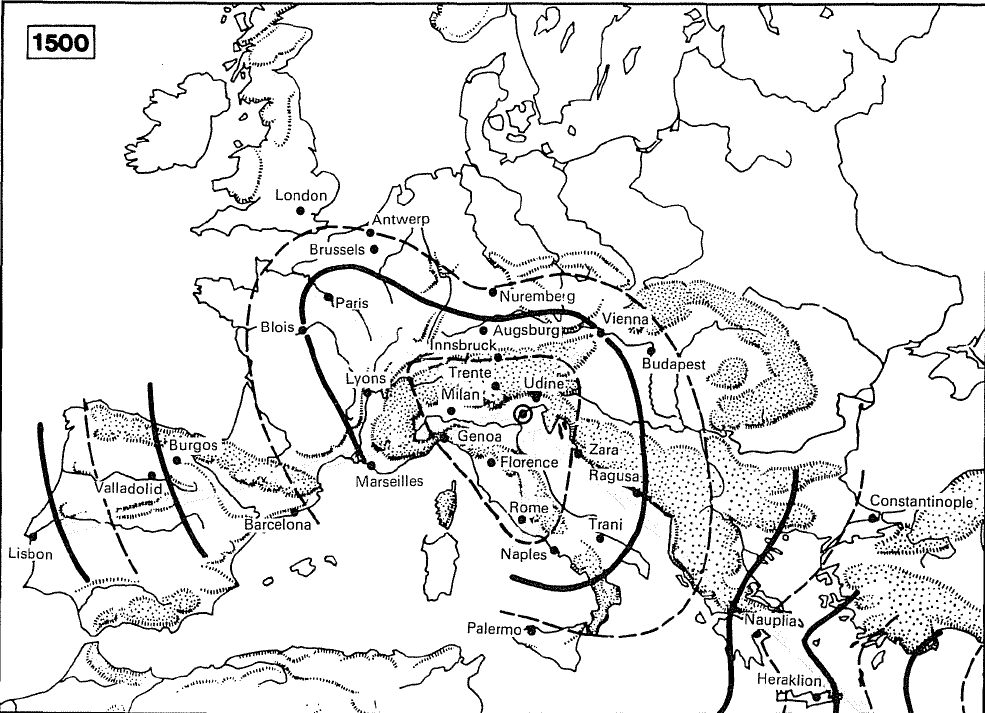

Soon after the War of 1812 breaks out, the Russian Tsar Alexander I gets wind and wants to broker a treaty. I don’t have primary sources in front of me, but let’s say it takes him at least a month to even hear about the outbreak of war, given the slow pace of early 19th C comms. Once he writes his letter, offering to broker a treaty, it takes a few months to get the proposal in both British and American hands. And then it takes another few months for American ambassadors to be selected and travel to Russia. By the time they arrive, the situation’s changed dramatically: Napoleon’s invading Russia, the tsar doesn’t have time for some backwater conflict, and the ambassadors kill six months waiting for a meeting. Finally, giving up on Alexander, they travel to London—which takes another month—and begin long drawn-out negotiations for peace.

Those negotiations are upended every time news comes in how the war’s going. If the Americans have had a prominent recent victory, their ambassadors gain leverage, and vice-versa for the British. But due to transit times, a “recent victory” is at least a month old. When finally a peace proposal is drawn up, it has to get shipped across the Atlantic again for the American government to read and ratify it. Once it’s ratified, messages have to be sent all over the word, to American ships and bases from Canada to the Caribbean. Andrew Jackson will make his name defending New Orleans from British attack, two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent. American frigates are still taking prizes six months into peacetime.

Two years then, spent trying to establish lines communications, trying to make progress on negotiations. All over a war that should never have started—that was in neither state’s interest—that broke out as a result of misalignments in the British military-governmental hierarchy. (The best argument for why the War of 1812 should never have happened is that the peace terms mark a return to pre-war status quo—i.e. neither party gained anything from the war. If this outcome could have been predicted in advance, then neither party would have had an incentive to go to war.)

So we begin to understand Kennedy’s anxiety when he’s trying to get letters passed to Kruschev in the Cuban Missile Crisis. We begin to understand why Kennedy insists on installing a telephone hotline between the superpowers: because you don’t want to be delayed by hours or days when a nuclear war can end the world in an hour.

Conclusion

It’s becoming well-established that China is gaining institutional capacity compared to the United States. They can build things much faster, much cheaper, much more reliably.

Much of this may simply result from relative industrial development tempos. But it’s also possible to draw several conclusions that are repugnant to Western worldviews: That there is a tension between individual freedoms and state capacity given alignment, like will-to-win, is critical to geopolitical struggles. America’s 20th C rise to power convinced many modern nations that internal demographic and ideological heterogeneity was not a hindrance, but in fact an advantage, in geopolitical struggle.

Is it possible that, in the evolutionary game of geopolitics, liberal ideas may not win? Authoritarian regimes may be better equipped to handle the spread of literal contagion, and they may similarly be better equipped to handle the spread of memetic contagion. In an age of information and mind war, is liberalism on the ropes?

And what are the counteracting dynamics, that might keep freedom alive? That might lead liberal political organization to triumph, in the end? Or at least, some post-liberal system that lives out Western values? There must be literature on this; I’d be indebted to any who link or cite in the comments. Market economies, at least, appear to outperform centralized economies pre-AGSI? And perhaps there is great power in the dialectical progress that free speech promises.

Perhaps it is natural and good populations bind together when threatened existentially, and fracture when wealthy and peaceful. In November 1941, there was mass support for the new state of Jefferson, splintering off from northern California and southern Oregon. Independence was declared, Route 99 was blockaded, and Congressional support quickly growing. In December 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Within 24 hours, the secessionists had re-pledged their loyalty to the Union.

Perhaps our fractiousness, as a nation, is not some unchangeable facet of liberal democracy, or of our decadence, but a rational response to our comfortable position of power. When core holdings are safe, you bargain over margins. “Bicker themselves into fragments,” is how Pynchon describes the post-Revolutionary War fallout, in Mason & Dixon. Then war came, and the fragments re-assembled.

Discuss