December 9, 2025

4 min read

Data Centers in Space Aren’t as Wild as They Sound

Space-based computing offers easy access to solar power, but presents its own environmental challenges

By Jeremy Hsu edited by Eric Sullivan

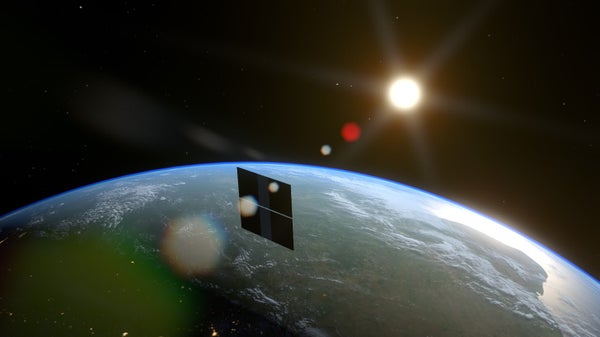

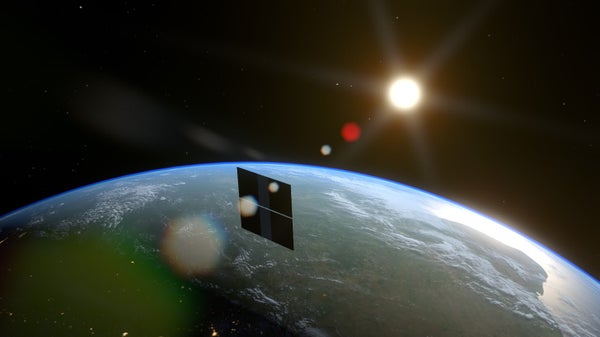

A mockup of the solar-powered data center the startup Starcloud plans to send into orbit.

Starcloud

To hear Silicon Valley tell it, artificial intelligence is outgrowing the p…

December 9, 2025

4 min read

Data Centers in Space Aren’t as Wild as They Sound

Space-based computing offers easy access to solar power, but presents its own environmental challenges

By Jeremy Hsu edited by Eric Sullivan

A mockup of the solar-powered data center the startup Starcloud plans to send into orbit.

Starcloud

To hear Silicon Valley tell it, artificial intelligence is outgrowing the planet that gave birth to it. Data centers will account for nearly half of U.S. electricity demand growth between now and 2030, and their global power requirements could double by the end of this decade as companies train larger AI models. Local officials have begun to balk at approving new server farms that swallow land, strain power grids and gulp cooling water. Some tech executives now talk about putting servers in space as a way to escape those permitting fights.

Orbital data centers could run on practically unlimited solar energy without interruption from cloudy skies or nighttime darkness. If it is getting harder to keep building bigger server farms on Earth, the idea goes, maybe the solution is to loft some of the most power-hungry computing into space. But such orbital data centers will not become cost-effective unless rocket launch costs decline substantially—and independent experts warn they could end up with even bigger environmental and climate effects than their earthly counterparts.

In early November Google announced Project Suncatcher, which aims to launch solar-powered satellite constellations carrying its specialty AI chips, with a demonstration mission planned for 2027. Around the same time, the start-up Starcloud celebrated the launch of a 60-kilogram satellite with an NVIDIA H100 GPU as a prelude to an orbital data center that is expected to require five gigawatts of electric power by 2035.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Those two efforts are part of a broader wave of concepts that move some computing off-planet. China has begun launching spacecraft for a Xingshidai “space data center” constellation, and the European Union is studying similar ideas under a project known as ASCEND.

A mockup of Starcloud’s orbital data centers, including an enormous array of solar panels.

Starcloud

“Orbital data centers would benefit from continuous solar energy, generated by arrays of photovoltaic cells,” says Benjamin Lee, a computer architect and engineer at the University of Pennsylvania. “This could resolve long-standing challenges around powering data center computation in a carbon-efficient manner.” Most proposals envision orbital data centers that would be in a dawn-to-dusk, sun-synchronous orbit aligned with the boundary between day and night on Earth so that their solar panels would receive almost constant sunlight and gain an efficiency advantage outside Earth’s atmosphere.

But the same physics that make orbital data centers appealing also impose new engineering headaches, Lee says. Their computing hardware must be protected from high radiation, through either shielding or error-correcting software. To cool off, orbital platforms need large radiators that can dump heat into the vacuum of space, adding significant mass that has to be launched on rockets.

All these plans ultimately collide with one stubborn constraint: getting hardware into space. Rocket launch costs alone pose a significant challenge to building large orbital data centers, not to mention the need to replace onboard chips every five to six years. “Launch costs are dropping with reusable rockets, but we would still require a very large number of launches to build orbital data centers that are competitive with those on Earth,” Lee says. Google’s Suncatcher team estimates that liftoff costs would need to fall to under $200 per kilogram by 2035 for their vision to make sense.

Even if they become economically feasible, orbital data centers may impose additional sustainability costs on the world. Starcloud estimates that a solar-powered space data center could achieve 10 times lower carbon emissions compared with a land-based data center powered by natural gas generators. But researchers at Saarland University in Germany, who published a paper entitled “Dirty Bits in Low-Earth Orbit,” calculated that an orbital data center powered by solar energy could still create an order of magnitude greater emissions than a data center on Earth, taking into account the emissions from rocket launches and reentry of spacecraft components through the atmosphere. Most of those extra emissions come from burning rocket stages and hardware on reentry, says Andreas Schmidt, a Saarland University computer scientist and a co-author of the paper. The process forms pollutants that can further deplete Earth’s protective ozone layer.

Astronomers have their own worries. Johnston says the ideal sun-synchronous orbit would only make orbital data centers visible in the night sky at dawn or dusk. But Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, notes that some observers rely on twilight to hunt for near-Earth asteroids, and she is wary of any orbital data center with a multikilometer solar-panel array. She also fears that such projects could worsen the growing problem of space junk, as more hardware is launched and more debris and fragments fall back through the atmosphere. “There’s so much pollution from reentries already and pieces hitting the ground,” she says.

For now, orbital data centers are mostly an idea, a handful of small prototypes and a stack of ambitious slide decks. The basic physics of near-constant sunlight in orbit are real, and launch costs are moving in the needed direction. But the environmental, astronomical and regulatory questions are pressing. The world will have to decide whether sending hardware into space is a clever way to power AI—or just a way to push its side effects out of sight.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.