The meteoric rise in the price of copper will likely continue thanks to a growing supply deficit that could reach 10 million metric tons — 25% of projected demand — by 2040, according to a new forecast from S&P Global.

Copper is critical for everything from phones and refrigerators to EV batteries, AI data centers, and battlefield drones. Yet new mines are still incredibly slow and expensive to open, and existing ones are becoming more costly to operate as the quality of ore declines. The market is already undersupplied, and in 2025 several of the world’s largest mines were temporarily closed because of disasters including mudslides, earthquakes, and collapsed tun…

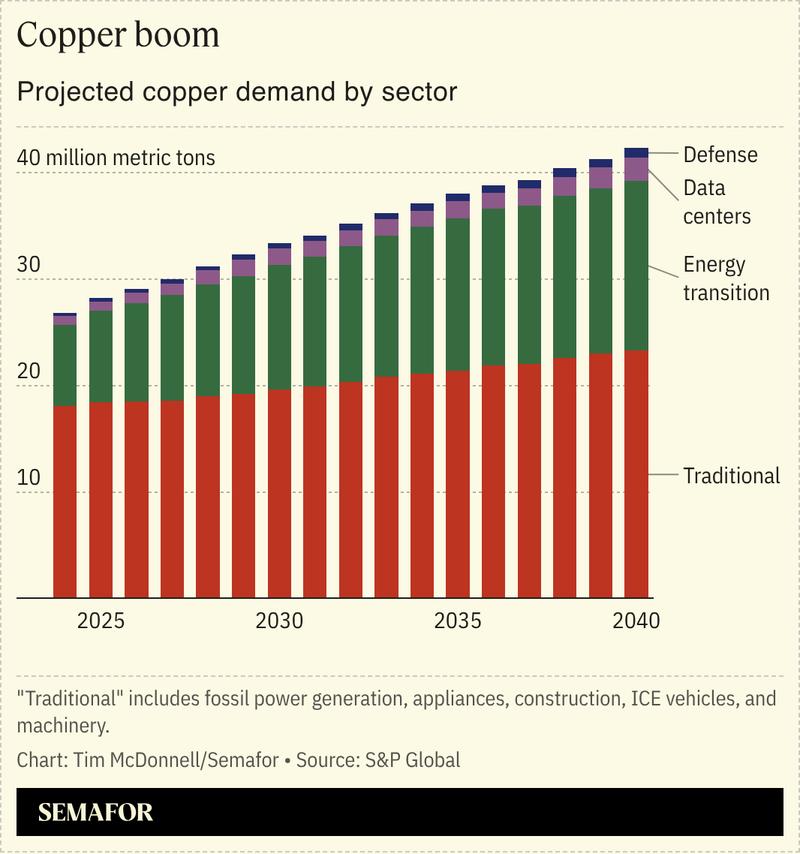

The meteoric rise in the price of copper will likely continue thanks to a growing supply deficit that could reach 10 million metric tons — 25% of projected demand — by 2040, according to a new forecast from S&P Global.

Copper is critical for everything from phones and refrigerators to EV batteries, AI data centers, and battlefield drones. Yet new mines are still incredibly slow and expensive to open, and existing ones are becoming more costly to operate as the quality of ore declines. The market is already undersupplied, and in 2025 several of the world’s largest mines were temporarily closed because of disasters including mudslides, earthquakes, and collapsed tunnels. Copper prices reached a fresh record Tuesday of $6.06 per pound.

Without policy changes to accelerate the development of new mines, increase recycling, and, most importantly, to forge new trade deals between suppliers, processors, and users, copper shortages will become a major constraint on the AI revolution and the energy transition, S&P Global Vice-Chair Daniel Yergin told Semafor. “The world is electrifying, and copper can be either the enabler or the obstacle.”

Copper is a conflict mineral of the future, an indispensable building block for critical technologies that has long been taken for granted but that will play an increasingly central role in US trade relations with China and Latin America—where most of the world’s copper production and processing capacity are located. The S&P study stresses that copper can’t be obtained at the necessary volumes or timelines through recycling or new mining alone. A 2022 S&P report pegged copper demand even higher, reaching above 50 million tons annually by 2040, but that was based on a “net zero” scenario in which renewable energy and EV use expand faster than they currently are. Even under the current pace of adoption, copper demand will still likely grow at least 1 million tons per year up to 2040, the new report found. Filling that need is a diplomatic challenge at least as much as an engineering one, with critical steps of the supply chain spread around the globe.

US President Donald Trump’s recent escalation in saber-rattling toward mineral-rich Greenland — whose deposits of copper are likely significant but remain underexplored — shows the administration’s willingness to exercise force to expand US access to raw materials. But taking minerals by force may close off access to other pieces of the supply puzzle by further ratcheting up protectionism on the part of other powers.

And it’s clear that an integrated global market is necessary for sufficient copper to get to where it is most needed. The US urgently needs to catch up to China on copper processing capability, which invading Greenland won’t help address: The US has only two functioning smelters, while China has dozens (which help to keep their costs low through the use of cheap renewable electricity, as well as plentiful supplies of heavily polluting coal). Saudi Arabia is also rapidly building out its copper refining capacity.

So for copper, the only path forward is through trade. “If we think it will be solved for the US by investment in the US, we’re never going to get there,” said Carlos Pascual, S&P Global’s senior vice president for geopolitics and international affairs.

Other factors besides simple supply-demand imbalance and mine closures are behind the current surge in prices, Yergin said. This includes the risk that copper will be caught up in Trump’s tariff wars, rising prices for gold which copper tends to follow, and cuts to the federal interest rate that could juice the US economy. New mines are still urgently needed, Yergin said, and while copper investors can’t react as quickly to price signals as, for example, shale oil drillers can — copper mines take an average of 17 years to develop — “when you get to these prices, that really gets people’s attention.”

Surging copper futures are especially driving revenue for African producers. DR Congo, which has tripled output in the last decade to become the world’s second-largest copper supplier after Chile, has seen its currency leap 28% against the dollar over the last year, while Zambia, also racing to boost copper mining, saw similar gains. Copper is key to African growth but countries across the continent face a familiar, and regularly unmet, challenge of ensuring that populations share the proceeds of extractive industries, Semafor Africa reported.

- The Trump administration’s threats to take military action against Greenland are counterproductive and needless, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board argues, and “even the suggestion of force is damaging America’s interests across the Atlantic.”