For this chore, the human touch still beats machines. But maybe not for long

Kaia Glickman, Knowable Magazine

December 8, 2025 8:08 a.m.

Robots still struggle with the unpredictable ways that fabric crumples and creases. But newer approaches offer the hope of better robotic household help. peepo/Getty Images

More than 60 years ago, Rosie the Robot made her TV debut in “The Jetsons,*” *seamlessly integrating herself into the Jetson household as she buzzed from room to room completing chores. Now, as reality catches up to science fiction and scientists work to develop modern-day Rosies, one of the most mundane tasks is proving to be a big challenge: folding laundry.

The ordinary-seemin…

For this chore, the human touch still beats machines. But maybe not for long

Kaia Glickman, Knowable Magazine

December 8, 2025 8:08 a.m.

Robots still struggle with the unpredictable ways that fabric crumples and creases. But newer approaches offer the hope of better robotic household help. peepo/Getty Images

More than 60 years ago, Rosie the Robot made her TV debut in “The Jetsons,*” *seamlessly integrating herself into the Jetson household as she buzzed from room to room completing chores. Now, as reality catches up to science fiction and scientists work to develop modern-day Rosies, one of the most mundane tasks is proving to be a big challenge: folding laundry.

The ordinary-seeming act of picking up a T-shirt and folding it into a neat square requires a surprisingly complex understanding of how objects move in three dimensions. Our own ease in accomplishing such tasks comes from a learned understanding of how different fabrics will respond when folded, even if we haven’t folded them before, but robots struggle to apply what they learn to new situations that may differ from their training. As a result, current robots are slow and often perform poorly on even the simplest of folding tasks.

Now, however, newer approaches that adapt better to real-world scenarios may lay the groundwork for robots folding our laundry in the future.

A big challenge in teaching robots the skill is the infinity of ways that various fabrics can fold. Think about all the times you’ve tossed a T-shirt into the laundry basket and how it landed in a slightly different-shaped heap each time. It’s simple for people to pick up a shirt and quickly find a sleeve or collar to orient themselves, but every unique way a shirt crumples is a new challenge for robots, which are often trained on images of unwrinkled clothing lying flat on a surface, with all features visible.

“It’s not the fabric itself that is the challenge. It’s the amount of variations that can be created by the way fabric can be crumpled, and all the different kinds of clothing items that exist,” says David Held, a robotics researcher at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

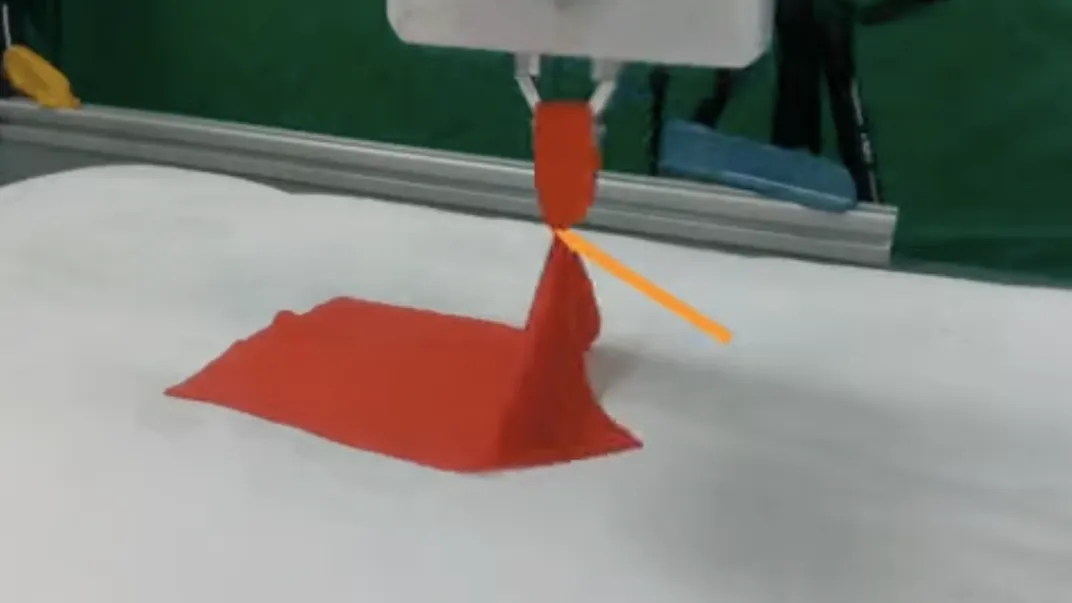

Pick and place

Today’s robots often use a strategy called “pick and place,” in which the robot uses a pre-determined move to manipulate fabric. This often fails to result in a good fold, because soft fabric can crumple or distort unexpectedly.

CREDIT: A. LONGHINI ET AL / ADAFOLD: ADAPTING FOLDING TRAJECTORIES OF CLOTHS VIA FEEDBACK-LOOP MANIPULATION 2024

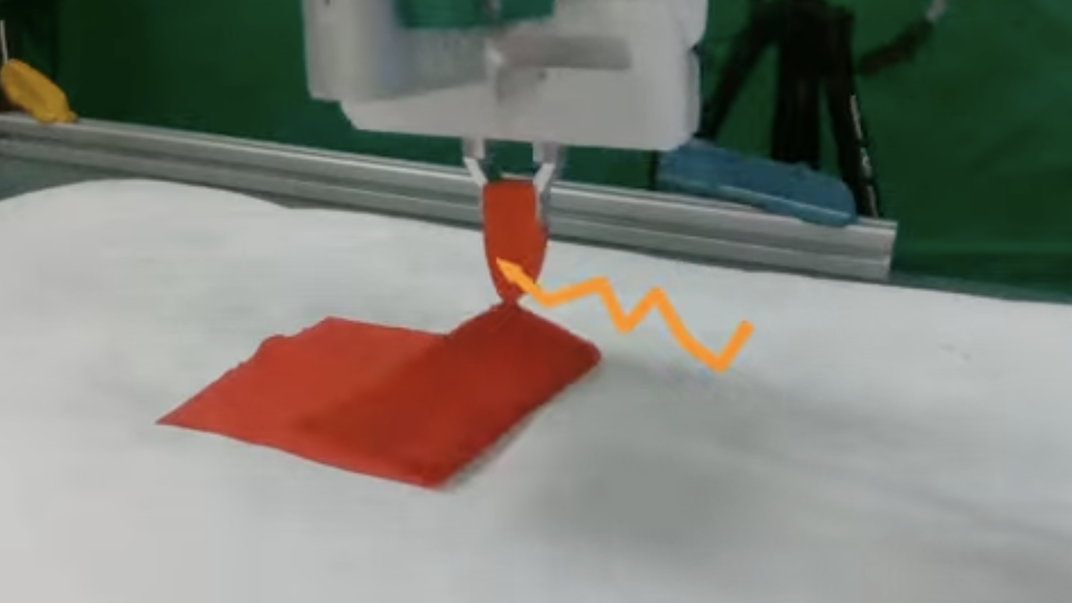

AdaFold

A newer folding algorithm, AdaFold, adjusts its folding path at each step to reduce crumpling and respond to dynamic changes in the fabric’s shape.

CREDIT: A. LONGHINI ET AL / ADAFOLD: ADAPTING FOLDING TRAJECTORIES OF CLOTHS VIA FEEDBACK-LOOP MANIPULATION 2024

That challenge is easier for people, because we are sensory sponges. Our eyes and hands provide a tremendous amount of information about the world through a lifetime of manipulating three-dimensional objects. Another result of all that learning is that simply looking at a piece of fabric gives us an intuition of how heavy or stretchy it is, and how it would best be folded. It’s clear to us that denim doesn’t fold like silk, for example, but robots don’t automatically understand that more force is required to lift and fold a pair of jeans than a delicate blouse and instead need to interact with the object before determining a folding plan.

Additionally, robots’ “hands” aren’t as versatile as ours. Many have grippers designed specifically for the size and shape of the object that’s going to be manipulated: A robot tasked to screw bolts into a panel of a car, for example, may have a gripper built to grab the exact size of the bolt. Laundry presents a challenge because the dimensions of fabric change with every maneuver, so grippers must be designed to adapt precisely to any shape and size of fabric.

“Humans have flexible hands covered by skin that can sense temperature, texture, whether something is wet or dry,” says Danica Kragic, a computer scientist at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden and co-author of an article about robotic folding in the 2025 Annual Review of Control, Robotics and Autonomous Systems. The long and short of it, Kragic says, is that “manipulating fabrics requires both advanced hand manipulation capabilities and high-level reasoning.”

Though robots often learn about the properties of real-world laundry by recognizing clothing features in images, more sophisticated approaches sometimes use physics to model fabric as a series of masses connected by springs, simulating the elastic nature of the material. But even these representations often don’t capture the true complexity of clothing. Scientists are working to shrink this reality gap, as researchers term such issues, by developing better data sets. An example is ClothesNet, a collection of 4,400 simulated three-dimensional clothing items, with features such as sleeves and collars labeled, to provide a more realistic representation for robots to learn from.

Once they have been trained on a fabric’s properties, many robotic systems use a folding strategy called “pick and place,” where the robot uses computer vision technology to identify a specific point on a shirt (like the left sleeve), then pick up that point and place it down at a different specified point (perhaps the right sleeve). In these models, the origin, destination and trajectory of the maneuver are pre-determined based on assumed properties of the fabric, such as stretchiness and weight**. **Though it may sound straightforward, the approach limits the ability of robots to adapt to real-time changes in the environment—such as a pair of pants being far heavier than expected, or a button getting in the way. Should such complications arise, the system can’t change its trajectory to complete a fold correctly.

Indeed, for this reason the results aren’t very good. Researchers often evaluate the success of a fold using a metric called Intersection over Union (IoU), essentially the amount of overlap of a material after it has been folded. A perfect fold would have an IoU score of 1, meaning the fabric was folded perfectly in half. In a 2024 study, pick and place scored a measly 0.41 when attempting to fold a rectangular piece of cloth in half.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/49/d849f316-df96-41fa-a4d6-4a7a2d9b96ba/g-measure-folding-performance.png) Folding success is often scored using a method called Intersection over Union (IoU), which measures how fully the upper half of a fold covers the lower half. A perfect fold overlaps completely, giving an IoU of 1; the score is lower if one half doesn’t match the other.

Folding success is often scored using a method called Intersection over Union (IoU), which measures how fully the upper half of a fold covers the lower half. A perfect fold overlaps completely, giving an IoU of 1; the score is lower if one half doesn’t match the other.

New technologies aim to make robots better at reacting to real-time changes during a folding task. One of these approaches is called AdaFold (named for its adaptive folding abilities). Unlike pick and place, AdaFold can change its plan in the middle of a fold. The model repeatedly monitors the fabric as it’s folding to gauge progress, adapting to changes in cloth shape and elasticity and adjusting when necessary to ensure the most overlap when the fold is complete. In the same 2024 study, AdaFold scored an IoU of 0.83.

The dynamic, adaptable response shown by AdaFold could help researchers more broadly to design robots that respond flexibly to the ever-changing human world. “We have this capability of recognizing that our intuition was wrong—we can easily adjust our internal representation of the object,” says Alberta Longhini, a co-creator of AdaFold who is about to begin postdoctoral research at Stanford University in California. “For robots, this is still complex.”

Until roboticists solve that problem, it’s unlikely that we’ll be able to consign laundry or other daily chores to robots like Rosie. Alas.

Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

You Might Also Like

December 5, 2025

December 5, 2025

December 5, 2025

December 5, 2025

December 5, 2025

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

- More about:

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Robots