Garnet is my attempt at making a programming language that could be summed up as “What if Rust was simple?” The goal is to make a small, borrow-checked language aimed at lower-level programming, designed for portability and robustness.

Low-level language landscape

This is about what I’ve been doing on this silly thing in the last year. If you want an overview of the language itself, check out the Sourcehut project page. Or, check out previous iterations o…

Garnet is my attempt at making a programming language that could be summed up as “What if Rust was simple?” The goal is to make a small, borrow-checked language aimed at lower-level programming, designed for portability and robustness.

Low-level language landscape

This is about what I’ve been doing on this silly thing in the last year. If you want an overview of the language itself, check out the Sourcehut project page. Or, check out previous iterations of this:

- TheStateOfGarnet2021

- TheStateOfGarnet2022

- TheStateOfGarnet2023

- TheStateOfGarnet2024

- TheStateOfGarnet2025

Last updated Jan 2026.

Compiler

The “rewriting the type checker” saga continues.

By early 2025 I had a proof-of-concept for a type checker that should do most of what I wanted from Garnet’s type system. I took that proof of concept, slapped it into the main compiler, made it work (though type inference is still a little janky), and made it monomorphize generics properly. And it all works quite well, all things considered. In theory terms, the type system is currently basically System F, minus existential types.

That took about six months. Then I asked “okay how do we make associated types like Rust’s actually work?” and “how do we make generics that can actually be used for anything?” and dove back into theory-land; see the Type System section below. I’m a bit concerned that Garnet has failed at its “don’t be a research project” goal… But I’m still having fun, mostly, and a friend I trust has assured me that I’m still on the “development” side of “research and development”. So despite some intense self-doubts, we’ll keep going.

Language

The fundamentals of Garnet are all pretty stable so far, they just don’t do much that’s super interesting ’cause it’s hard to do that while the type system is in flux. A statically-typed language without user-definable generic types is limited to basically C/Pascal-like levels of sophistication, so you need powerful generics to do much interesting work with pointers, arrays, etc unless they’re special-cased into the language somehow. Turns out getting a language to that point is actually very easy, and getting it much past that point is pretty hard. But I did manage to do some Actual Cool Language Stuff:

Pattern matching

It doesn’t actually work yet, but I played with some pattern matching ideas based off of The Penultimate Conditional Syntax. I like it a lot, since instead of having match and if expressions and eventually having them grow into a Rust-like zoo of if let, while let etc, you just have an expr is pattern pattern-match expression that returns true when the match is successful. So you can write thing is Some(x) to test for a match like Rust’s matches!() macro, if thing is Some(x) then ... end to get Rust’s if let, and if you have a long chain of if cases containing pattern matches then the compiler can pretty easily notice and optimize them into something like Rust’s match, complete with exhaustiveness checking. Then you make some syntax sugar for long chains of if/elif/else’s, and tada, you’ve built powerful pattern matching out of interchangeable parts.

The problem with this is that the expression thing is Some(x) introduces a new variable, x, but only when the match is successful. Currently in Garnet if you write if test_expr then true_expr else false_expr end then variables bound in test_expr don’t exist in true_expr. And they definitely don’t exist in false_expr. So, implementing the is expression is pretty easy, but making it actually bind variables inside if exprs requires rewriting a whole bunch of the compiler’s assumptions about how variable scope works. Most languages that heavily use pattern matching like OCaml or Erlang make a failed match into a runtime error, so “how do you have a variable bound in one subexpression but not in another” just never comes up for them. But I don’t want that to happen in Garnet, I want to have always-exhaustive patterns like Rust does. The easiest way out of this corner results in something a lot like Gleam’s use expression, where if statements turn their body into closures and calls the correct ones with the variables bound in the test. So this:

if thing is Some(x) then

x + 1

else

other_stuff

end

is actually syntax sugar for something more like this:

-- `expr is pattern` returns true or false, and a sneaky list of bound variables

let (matches, env) = thing is Some(x)

let if_expr = fn(env) -> env.x + 1

let else_expr = fn() -> other_stuff

if matches then

if_expr(env)

else

else_expr()

end

This feels rather silly and circuitous, and it means that binding a variable in a pattern outside of an if or similar thing is simply invalid. But I actually haven’t come up with an easier way that doesn’t require a dedicated match syntax for pattern matching like Rust or OCaml does. And these generated closures proooobably fall into the class of “easy for the compiler to recognize and inline”, so runtime performance isn’t much of a worry. Just one of those unexpected speedbumps you run into when you take a neat idea and then try to run with it for real.

Properties

I also played with properties a fair bit, even if they still barely exist in practice. It’s basically settled: in language theory terms, Garnet’s properties are effect types with inference. Unlike most languages with “effect systems” there’s no effect handlers or coroutines or such though, just effect types. I considered just calling them “effects” instead of making up a new term for them, but a) languages with “effect systems” like Koka tend to use the term to mean like 3 different interleaved features with fuzzy boundaries, and Garnet’s properties are just one of those. And b) everyone I asked said “if I see an language advertising ‘effects’ as a feature I assume it’s a research toy”. So, they’ll remain “properties”. Gotta shape the reality you want to live in.

What are properties in practical terms? Well, have you ever wished you could tell Rust “the function foo() can’t panic, and if I write something that would let it panic then it’s a compile-time error”? Cool, me too. That’s basically the idea for Garnet’s properties, extended to all sorts of things you can say about a function or data type: stack usage, nontermination, purity, unsafeness, etc. Currently they’re just compiler built-ins, a list of things the compiler knows how to prove about a program. But there’s no real reason users can’t extend them to their own features eventually.

Properties are both easier and harder to implement than they look, though. They’re easier because they can be somewhat lossy: you don’t always have to prove that the function foo() does panic, just that it can. So much like Rust const expr’s you can have a fairly simple algorithm that allows some false positives, as long as it still never produces false negatives. The somewhat half-assed prototype code for this is less than 100 lines.

But properties are also harder than they look because they really do act like types. If you have a higher-order function like fn map[T, U](v: Vec[T], f: fn(T) U) Vec[U], and you write it in such a way that it can’t panic (maybe you’ve pre-allocated the output vector), then it’s easy to prove that it can’t panic… Unless the function f you pass into it panics. Then your map() function can now panic by calling f(). So much like like generic types, properties are kinda sticky and tend to bubble up through your program’s function signatures.

Hopefully you won’t need to worry about properties 98% of the time. Most computers have plenty of resources, constraints can be loose and the compiler can infer all the function and type properties that it needs to care about without you having to boss it around. Great! Properties are for the last 2% where you need to be very explicit, and in my conceptual tests they do tend to generate a big fat morass of type-like annotations and preconditions and stuff. Buuuuuut I suppose that’s inevitable for code that concerns itself with the low-level details. If you actually care about them that much, then writing out an extra 5 lines of function annotations is probably better than 20 lines of comments explaining how you promise this function can’t panic as long as the assumptions A and B and C are true…

Tooling

Not a whole lot of work here, though I played with writing a tree-sitter parser and doing some basic Helix editor integration. It doesn’t even do syntax highlighting correctly yet, but it’s at least enough to make writing integration tests not entirely horrible. I must be one of the only 3 people in existence who doesn’t find much fun in endlessly tinkering with text editors.

Type system

I’m basically on year 5 of trying to write a type checker. Sigh. Turns out there’s reasons that Rust is the only remotely production-quality language that has really done the sort of things I want Garnet to do… Life would be infinitely easier if I could pretend everything is a pointer like OCaml or Lisp does, or if I could pretend every function call is a vtable like Go or Java does, or if I could lean on a JIT to figure out everything at runtime like C# or LuaJIT does. But you need a memory-safe language to write all the tooling underneath that stuff, and there aren’t many of them, so I’m making Garnet.

Almost since the beginning Garnet has looked at Rust traits/typeclasses and said “why are these their own special thing in the language? Why are there all these word-of-god rules about how they work?” Trait definitions look a lot like a type: they’re just a struct type full of functions. Then trait implementations are just a value of that type, with the functions filled in. What’s the big deal? Can’t you just write traits as struct types and values? So I’ve always tried to just run as far with that formulation as possible.

Welllllll, long story short, once you add generic types it Gets Complicated. And then when you want to add any non-trivial feature beyond the most bare-bones generics, it Gets More Complicated. (The “simpler Rust” I wanted probably doesn’t exist. That’s okay, I’m still doing what I can.) Startlingly quickly your type checker grows most of the features of an interpreter, and you either do the “template” approach to generics like Zig/Odin/D and just generate code and hope it typechecks with a simpler type checker, or you do the “real generics” approach like Rust/OCaml/Haskell and try to prove the types are correct before generating code. If you do the “real generics” approach and try to push it further than Rust does, you descend incredibly quickly into a morass of dependently-typed languages full of theorem provers and other such headache-inducers. Making a nice, small low-level language with dependent typing not an impossible problem to solve, I suspect in 10 years we’ll start to have some pretty great languages built around that sort of thing, but for now it’s still mostly in the realm of “research project”.

Fortunately, a few years back I stumbled upon a slightly underappreciated paper defining a research language called 1ML, descended from OCaml/SML modules. 1ML claims to straddle the boundary between traits and more complicated type systems, getting you a very trait-like set of language features by starting from a “structs full of functions” model. It also builds its trait-equivalents out of simpler pieces without an entirely parallel sublanguage of “looks like types but different”, and does it without dependent types. This seemed ideal, and while the complete 1ML paper with all the math is massive, the basic version of the paper is only 13 pages. So while I didn’t fully understand all the details of it yet I was pretty sure I could figure it out. What I want to do is possible to do, someone else has figured out how, it’s just a small matter of programming

Easy, right?

So, remember how in 2024 I read through the Types And Programming Languages textbook? in 2025 I read through the full version of the 1ML paper, all 50+ pages. And I barely understand a word of it, so I also read through the 70+ pages of its predecessor paper, evocatively titled “F-ing Modules”. Then I read through the 1ML paper again. A few times. And I still didn’t understand most of it, so I went to the PLTDI Discord server and annoyed a bunch of people who are way smarter than me to help figure out all the details. And in the process I discovered something very, very important:

1ML is weird.

And I mean weird even for type-theory research papers. It looks pretty straightforward at a glance, but fucking nobody I talked to seemed to actually understand all the technical details holding it together. People who were good at ML module systems couldn’t explain them all. People who were good at type theory couldn’t explain them all. And 1ML has a lot of technical details when you dig under the surface.

In principle the 1ML paper works by taking its ideas and translating them down into lower-level math that is all fairly conventional, but that translation is put together in a somewhat unconventional way which takes a fair bit of work to figure out even the simplest bits. The notation they derive for it is sugar-heavy and built out of some very recursive definitions and is generally excessively clever, which makes it hard to figure out how all the pieces fit together because they all depend on each other. There’s a reference implementation, but it’s also written in a somewhat obtuse way that makes it hard to suss out all the details. As research code goes it’s pretty okay, but you don’t have to do much digging to realize it’s not a straightforward implementation of the paper’s proofs, but rather experimental code that has been cleaned up for publication. No shame in that, but it’s a lot of work to get anything useful out of it.

So 1ML demonstrably works, but figuring out all the details of how the hell it works has at one time or another baffled many smart people. Out of dozens of skilled language nerds and several real researchers, only one actually seems to have actually understood 1ML from end to end. I still do not count myself among their number.

The problem is that 1ML is very clever. It’s too clever. In design terms it feels a lot like Hindley-Milner type inference, where it balances very finely on the cusp of what is possible. It’s a perfect, crystalline collection of features that fit together in juuuuuust the right way. And that makes me worry quite a lot. What if, like HM type inference, departing from that balance will make it fall apart and rapidly plunge you into chaos and agony and The implementation does not match the interface: "val foo : bytes -> int -> unit" is not included in "val foo : bytes -> int -> unit"?

I do not want Garnet to be built around a complicated, fragile, and difficult-to-implement theory. Garnet is supposed to be simple, robust and pragmatic.

Buuuuuuuut I didn’t have many other ideas besides giving up, so I kept digging for a while. HM type inference becomes much more tractable and useful when you change a few of its basic assumptions: you can make top-level functions and types require annotations, infer the rest of the program, and it works extraordinarily well and fails in fairly predictable ways. And there are other approaches to type inference than Hindley-Milner, with different tradeoffs. Can we change some of 1ML’s assumptions to transform it into something simpler and more robust? After a few more weeks of pondering it, somewhat to my surprise I think it’s actually pretty simple:

- Chill out on type inference.

- Ditch subtyping.

First, type inference. 1ML is a language very much in the OCaml lineage, so it puts a lot of work into making global type inference work, and there’s several major features in it mainly to help with that inference. But as mentioned, type inference is a double-edged sword, and global type inference is imo outright undesirable in most programs. As long as type inference mostly works and doesn’t tend to lead you down infinite rabbit-holes of erroneous suggestions, you can make useful programs without needing all that much sophistication. For example, Zig’s type inference is relatively primitive but still very nice to use in practice. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it has to be Good Enough.

Next, subtyping. One of the great things about Rust is that it has almost no subtyping outside a few rarely-used features, and thus demonstrates vividly how often subtyping is a trap. Sure, subtyping is legitimately useful sometimes, but most of the Rust code I’ve written that used subtyping has ended up being refactored to replace it with simpler and less problematic abstractions. So I’ve always been very leery of having subtyping in Garnet. However, ML-style module systems actually rely a lot on subtyping, in many sneaky places and in many unspoken ways. 1ML puts a lot of effort into making subtyping work, in such a way that ensures the type checker actually terminates and still functions in the presence of type inference. What if we just… take it out?

The result is… well, still very weird. But it actually seems pretty tractable:

- Types are just constant (compile-time) expressions, with the type

Type(not to be confused with kinds, sigh) - Defining a type is just a normal expression like defining a constant value

- You can stick most normal expressions anywhere you need a type, as long as the expression’s return type is

Type - Which expressions are valid to use in a type are restricted, in slightly complicated ways, but it mostly comes down to “stuff that can be evaluated purely at comptime, like Rust’s

const”. But it includes “function calls that returnType” though, which gives you a whoooole lot of power.

So if I try to conjure up a type system around those rules, the following code is theoretically all valid, though I’m omitting a fair few details:

fn Vec(T: Type) Type = ... end -- Similar to Rust's Vec::<T> type...

const MyVec: Type = Vec(I32) -- ...but this typedef is just a function call.

-- Similar to defining a new trait:

const Iterator: Type = struct

Item: Type,

Collection: Type

State: Type,

-- give it some methods (just function pointers)

next: fn(State) Option(Item),

...

end

-- Implement the "trait" for our new type

const MyVecIterator: Iterator = {

.Item = I32,

.Collection = MyVec,

.State = USize, -- Just store our current position in the vector

.next = fn(State) Option(Item) = ... end

}

-- Write a function that works on any Iterator,

-- it can refer to the iterator's types like Rust associated types.

-- (don't worry about an add() method for now, but we can do that too)

fn sum(impl: Iterator, collection: impl.Collection) impl.Item =

...

end

-- Finally, use it.

let data: MyVec = make_some_data()

let result: I32 = sum(MyVecIterator, data)

Notably, this seems to get some very dependent-type-looking features, while dodging the complexity of full deptypes. Unlike deptypes, every expression only ever has one correct type, I think the type checker always terminates, and you don’t need a math degree to write code in it. It even fixes some issues ML modules tend to have, such as being able to express both applicative and generative functors – ie, you can write Rust’s “newtype struct” pattern, while still being able to tell that the type equality OrdSet(Int, CmpAscending) == OrdSet(Int, CmpAscending) is true and OrdSet(Int, CmpAscending) == OrdSet(Int, CmpDescending) is false. It’s still a pretty weird type system, but you seem to get a lot of very useful and powerful features out of just a few features.

The main downside of all of this so far, it’s rather wordy. Sad, but I always knew this was gonna be the case. I don’t want to just make Rust traits, and type-driven dispatch like Rust traits can do a lot of heavy lifting when it comes down to telling a computer to just do what you want it to. But I’m optimistic that a careful and not-too-thick selection of syntactic sugar can bring it down from Ada levels of verbosity to something more like Erlang levels.

The other big downside is that this turns your type checker into even more of an interpreter, on purpose this time. This sounds pretty slow, and I want my type checking to be fast. But the only things it ever interprets are pure functions with pure inputs, so hopefully we can just memoize away a lot of the overhead and keep our namespaces small. That way the type checker interprets lots of small programs in parallel, without having to redo redundant work, instead of having to run one big serial program all at once. It’s still a spooky thought though, so we’ll see how well it works out…

A smaller downside is that to be able to to be able to interpret functions-returning-Type sensibly, you basically need some form of effect types to track function purity. Oh wait… Garnet has that ability already from its function properties! Almost like I planned it this way. I didn’t, but it’s not a coincidence, just convergent evolution. There’s a lot of pieces of 1ML that look suspiciously like other features I already want; there’s some profound symmetries roiling around somewhere under the surface there.

Oh right, the last downside: I haven’t implemented it yet. So I’m starting 2026 by diving into Type Checker Rewrite #5.

Conclusions

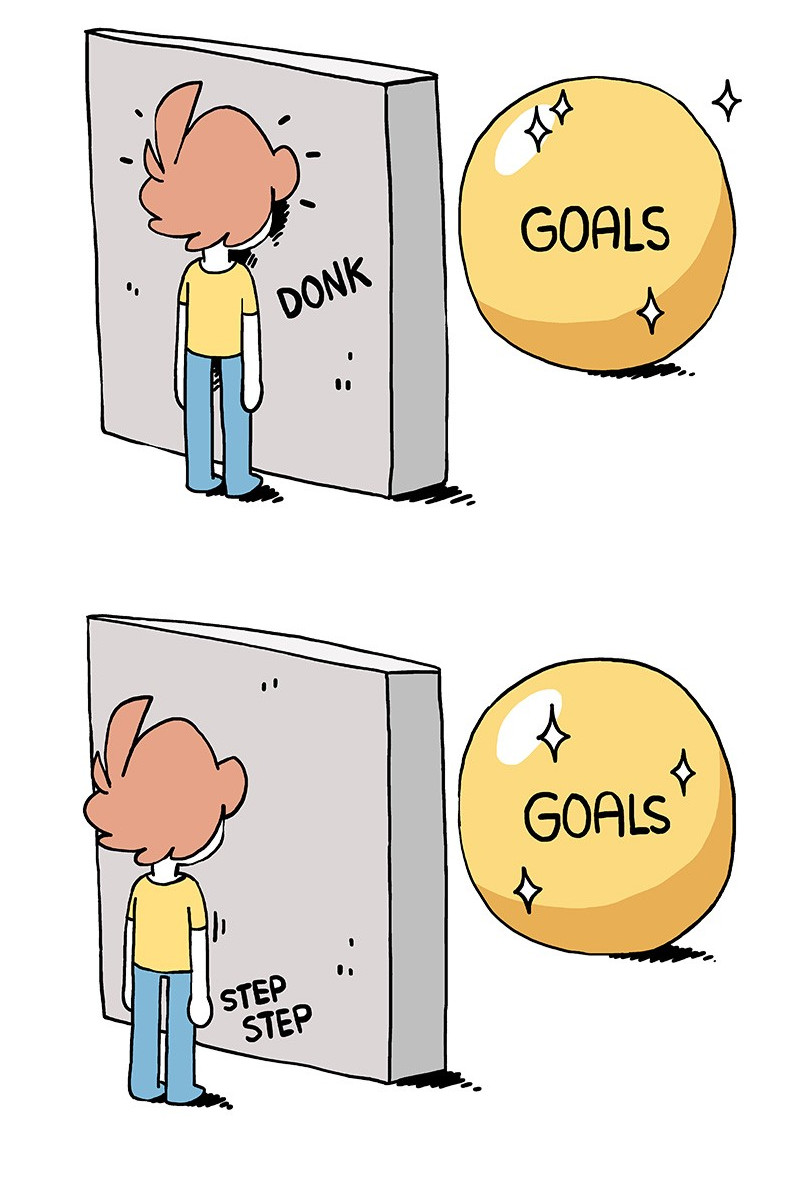

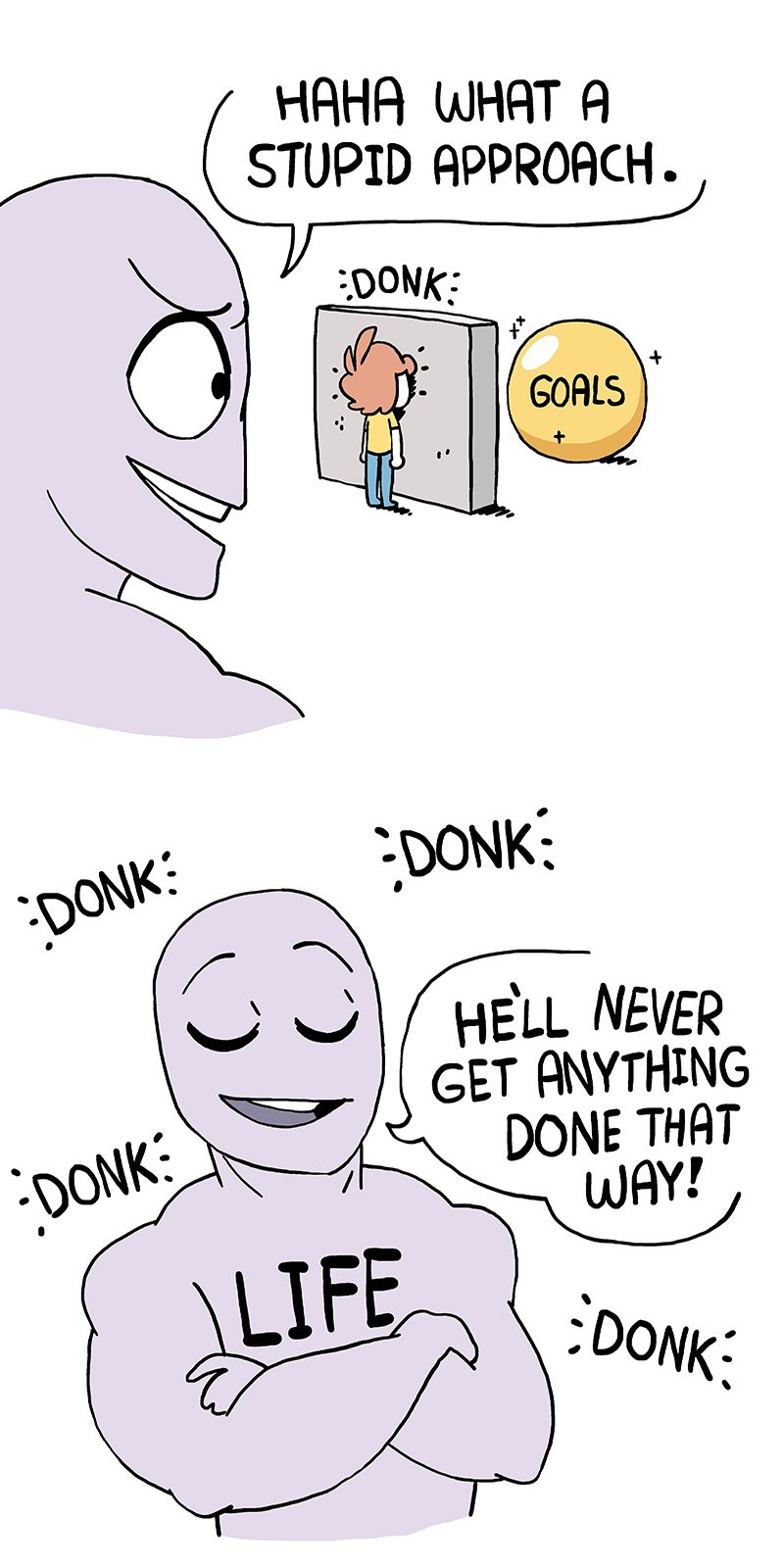

To reprise last year, my face is still more durable than concrete walls.