Let’s talk about transformers, dear readers. Not robots in disguise, but the neural network architecture that underpins basically every modern AI model. Transformers are smart, but they trade training efficiency for inference complexity. To help reduce the amount of compute needed for complex transformers, we use a thing called a Key Value cache, or KV cache. This stores pre-computed rarely-changing values in memory so that we don’t have to re-compute them for every single output token, as you otherwise would, radically accelerating performance.

Without a KV cache, transformers become virtually unusable, but the KV cache is very large on [modern bleeding-edge (or "frontier") AI models](https://hothardware.com…

Let’s talk about transformers, dear readers. Not robots in disguise, but the neural network architecture that underpins basically every modern AI model. Transformers are smart, but they trade training efficiency for inference complexity. To help reduce the amount of compute needed for complex transformers, we use a thing called a Key Value cache, or KV cache. This stores pre-computed rarely-changing values in memory so that we don’t have to re-compute them for every single output token, as you otherwise would, radically accelerating performance.

Without a KV cache, transformers become virtually unusable, but the KV cache is very large on modern bleeding-edge (or "frontier") AI models that support massive context windows and also come with extremely long system prompts. That means it takes up precious space in the very limited HBM available to each GPU.

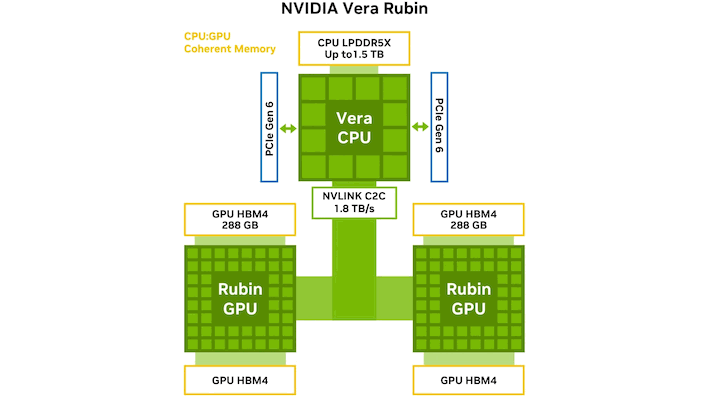

Image: NVIDIA

Image: NVIDIA

NVIDIA’s Vera Rubin servers solve this by using an incredibly high-bandwidth NVLink interconnect between the Rubin GPUs and the Vera CPU. That way, they can use the up-to-1.5-TB of LPDDR5X memory connected to the Vera CPU to store the KV cache, and rapidly copy it back to GPU HBM when necessary. It’s a clever solution to the problem, and it doesn’t look like AMD’s MI455X has a comparable interconnect between CPU and GPU.

It’s not as if AMD is ignorant to the issue, though, and based on renders, the company’s solution to the issue of "what to do with the KV cache" appears to have been "add a bunch of LPDDR5X to the GPU module." The question then becomes "where are the memory PHYs," or, in other words, "what chip does the LPDDR5X connect to?" Does it have a bunch of LPDDR5X memory controllers on-die as well as the on-package HBM? Maybe—but maybe not.

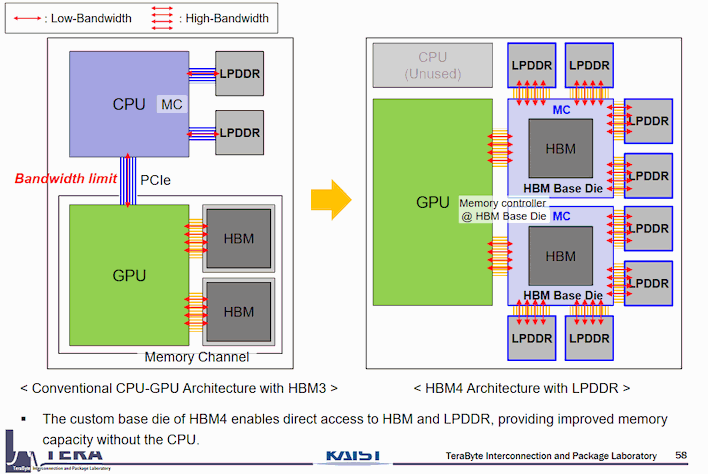

Image: KAIST TERALAB

Image: KAIST TERALAB

In a September 2025 presentation from KAIST (South Korea’s top science and technology university) and that university’s TERALAB, titled "[HBM Roadmap ver 1.98] Overview of Next Generation HBM Architectures," Professor Joungho Kim explains that with HBM4, it’s possible to use a custom base die underneath the HBM stacks that includes its own memory controller, and that LPDDR packages can be connected directly to the HBM base die. This is clearly illustrated in the slide above.

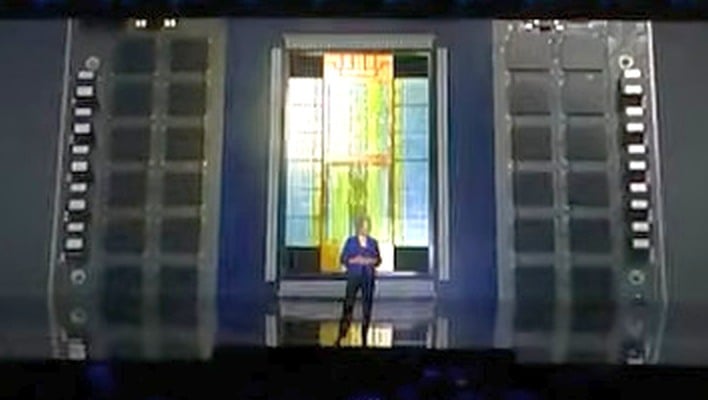

AMD’s MI455X is known to indeed be using HBM4, so it’s entirely possible that this is the actual memory architecture of Helios, AMD’s upcoming full-rack compute solution. "But Zak," I hear you saying, "AMD didn’t say anything about LPDDR memory capacity in its presentation!" You’re right, and yet, in the video that AMD showed behind CEO Dr. Lisa Su at CES, you can see the assembly of an MI455X compute module, and in that video, you can clearly see a huge pile of what definitely look like LPDDR5(X) packages flanking the massive MI455X chip. See for yourself:

From AMD’s CES 2026 keynote. Note the LPDDR packages to either side of the GPU.

From AMD’s CES 2026 keynote. Note the LPDDR packages to either side of the GPU.

So where NVIDIA has integrated the CPU into the GPU fabric as a coherent system, AMD seems to have taken the other path: demoting EPYC to the role of orchestrator and coordinator while linking all of the GPUs, their HBM, and their local LPDDR into one big accelerator using UALink, the Ultra Accelerator Link protocol devised by basically every big tech firm that’s not NVIDIA, including AMD, Intel, Broadcom, Meta, Microsoft, Google, and more.

To be clear, this is mostly speculation at this point. We’re working off of what could be a non-representative render and a plausible theory formed from scientific research and unexplained spec-sheet differences. Still, we’re not the only ones to come up with this idea. In fact, SemiAnalysis posted about it way back in April, apparently—though that site’s commentary is paywalled, so we don’t know exactly what they said.

Which approach is superior? We simply don’t know yet, and we won’t until third-parties get their hands on Vera Rubin and Helios to put the two different machines through their paces. It’s interesting to see how sharply AMD and NVIDIA have diverged on distributed systems design, though. AMD is claiming some big specs versus the promises NVIDIA has made for Vera Rubin. We’re eager to see how this all plays out, likely toward the end of this year.

Shout out to Gray for pointing out this rabbit hole that we dove down.

A 30-year PC building veteran, Zak is a modern-day Renaissance man who may not be an expert on anything, but knows just a little about nearly everything.