Exactly twelve years from now, on January 19, 2038, at 03:14:08 UTC an unpredictable amount of computer systems will think they have been teleported in time more than 100 years, back to December 13, 1901. When that happens, millions of systems across all sectors of society, ranging from consumer products like smartphones, watches, household camera security systems, and car infotainment systems, to more critical devices like payment systems, medical devices, gas stations pumps, and critical industrial control systems, will suddenly start behaving in unpredictable ways.

We are talking about a synchronized planetary event wit…

Exactly twelve years from now, on January 19, 2038, at 03:14:08 UTC an unpredictable amount of computer systems will think they have been teleported in time more than 100 years, back to December 13, 1901. When that happens, millions of systems across all sectors of society, ranging from consumer products like smartphones, watches, household camera security systems, and car infotainment systems, to more critical devices like payment systems, medical devices, gas stations pumps, and critical industrial control systems, will suddenly start behaving in unpredictable ways.

We are talking about a synchronized planetary event with catastrophic potential. I wish there was a way of saying this without sounding some sort of doomsday apocalypse prophet. This isn’t that. And I wish this was some sort of marketing stunt, we would all be better off. But this isn’t that either.

This will happen. This has a fixed and known date. This is unavoidable. The only thing that we can change and try to control is how big the impact will be. By the time you finish reading this blog post, I hope it becomes clear to you that action is needed and we need to start working toward remediation as soon as possible. To understand the risk, we need to briefly understand where it comes from.

What exactly is the Y2K38 problem?

It all has to do with a very common (though not the only) way that computers store time: Unix time_t. Don’t be fooled by the name, this is not about Unix, not anymore anyway. Unix time is a way of measuring the amount of time that passed from a fixed date, called the epoch. Unix was already using the “seconds-since-epoch in an integer” model in the mid-1970s. Very early Unix timekeeping experimented with different epochs before settling on the now-standard 1970 epoch. The typedef name time_t crystallized in the ANSI C standard (C89, i.e., 1989) and later POSIX standardization. The Linux man-pages explicitly list time_t C89 as its origin in standards terms. This simple, elegant idea makes tracking and computing with time a relatively simple matter.

Interestingly, the first edition of the Unix Programmer’s Manual (1971) actually defined time as "the time since 00:00:00, Jan. 1, 1971, measured in sixtieths of a second". Why the sixtieth of a second you ask? Because the PDP-11 computer used a "Line-Time Clock" that generated an interrupt at the AC power frequency (60Hz in the US). The frequency of the power grid actually defined time. But that was not quite useful, since this high resolution meant a 32-bit counter would overflow in only ~2.5 years.

The implementation of this idea eventually settled on time_t, defined as a 32-bit signed integer representing the number of seconds elapsed from 1970-01-01 00:00:00 UTC. This means that Unix Time spans from integer value -2 147 483 648 or 1901-12-13 20:45:52 UTC to integer value 2 147 483 647 or 2038-01-19 3:14:07 UTC. Dennis Ritchie, co-creator of C, is quoted to have said: ”‘Let’s pick one thing that’s not going to overflow for a while.’ 1970 seemed to be as good as any.” So time_t ends on January 19, 2038. What happens next is a rollover, effectively resetting time back to the start: December 13, 1901. Visually, it looks like this:

How deep does it go?

This is a tough one to answer and it is precisely part of the problem. Anything that uses C (or C-derived ABIs) and needs time. If a system is written in C, C++, or links against libc / POSIX APIs, there is a very high chance it either uses time_t directly or uses something that uses time_t internally. As you can imagine, that includes far more than Unix itself: Linux, BSDs,Solaris, AIX, HP-UX, VxWorks, FreeRTOS, Embedded Linux and BusyBox-based systems, Android (Bionic libc), are some other operating systems examples that use it.

But this is just the start. The problem is not even delimited by the operating system at all: core system libraries (including Windows MSVCRT), file-systems, database and data format fields, network protocols, embedded devices, firmware, and other programming languages (Perl, Python, PHP). All those are examples where time_t can manifest itself. The sheer volume of systems reliant on or utilizing time_t across our current planetary installed base is just overwhelming. They are, quite simply, everywhere.

Isn’t there a quick fix?

The good news is that there is a technical fix: time64_t! Instead of using a 32-bit integer, we use a 64-bit integer. Easy. This will also roll over, in approximately 292 billion years (which is many times the current age of the universe), so it will likely buy us enough time to think about another solution. However, replacing time32_t for time64_t in practice requires updating not just code, but software development toolchains, ABIs, shared libraries, kernels and (frequently) hardware itself. That complexity is precisely where the challenge lies. Nowadays most systems are 64-bit based and, in theory, are not vulnerable to the 2038 rollover anymore. Good news, right? Reality, it seems, is slightly more complex. Well… considerably more complex.

The bad news is that there is still a non-trivial amount of systems that are vulnerable to the Y2K38 vulnerability and we don’t know exactly how many or even where they are. Even 64-bit based systems can be vulnerable if they are, for example, using an old 32-bit binary or dataformat. And by non-trivial, we mean millions.

What can we see?

Leveraging our internal data sources has allowed Bitsight to start to gauge this problem. Measuring the amount of vulnerable systems at scale and with certainty is an extraordinary challenge, given the diversity of systems and the part of their stack that they can be affected. It is impossible to remotely assess all existing systems to begin with: there will be a big part, if not the biggest, that are not connected to the Internet at all.

But we can assess those systems that are reachable. There will be cases where it is possible to identify with confidence that a system is vulnerable and there will be cases that we need to consider a probabilistic approach. Both approaches help to determine the extent of this problem. Let’s look at some examples of things we can measure. For example, we can scan for server-side services that provide details about the underlying operating system, architecture and protocols.

NTP

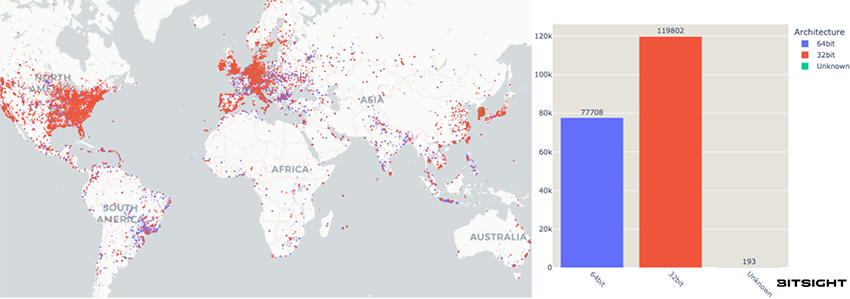

The Network Time Protocol (NTP) is a critical standard used globally to synchronize computer clocks. It is utilized across a vast range of systems, including critical infrastructure. By analyzing this service, we can sometimes gain visibility into the underlying platform. We took a sample of approximately 1.5 million public-facing NTP services reachable, and out of those, roughly 200 000 provide enough details about their underlying version and architecture to perform a targeted assessment of their Y2K38 vulnerability risk.

Almost 60% of the reporting NTP servers are still running on old 32-bit operating systems. While the exact moment of failure cannot be universally certified without extensive testing, this architecture places them at a high risk of catastrophic failure on January 19, 2038.

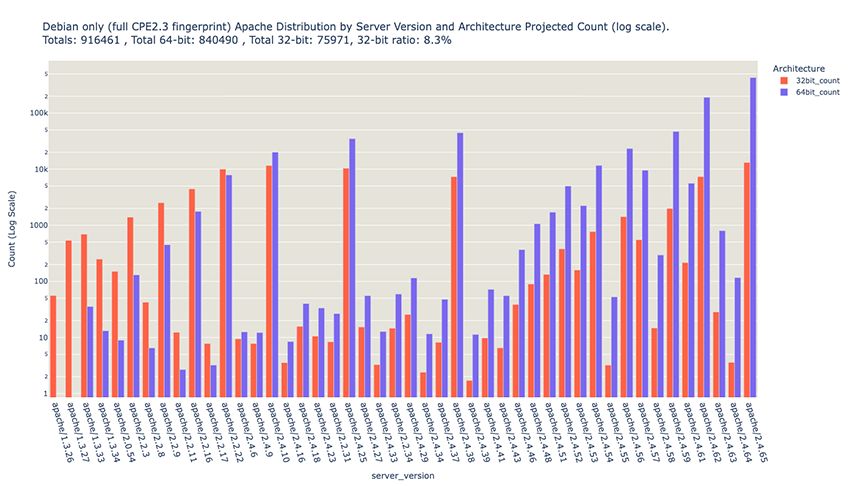

A much more popular service, like web servers, is even more challenging, given that the servers rarely report the underlying architecture. Can you tell if the system is vulnerable to Y2K38 given a HTTP version string? It depends on the server software and version. Take these two examples: Bitsight sees around 900 000 Apache Debian and 500.000 Boa Web servers reachable via the Internet. These are servers that clearly identify with strings like Apache/2.4.61 (Debian) or Boa/0.94.13. There might be more that contain no version strings. But let’s focus on these for now.

Apache Debian

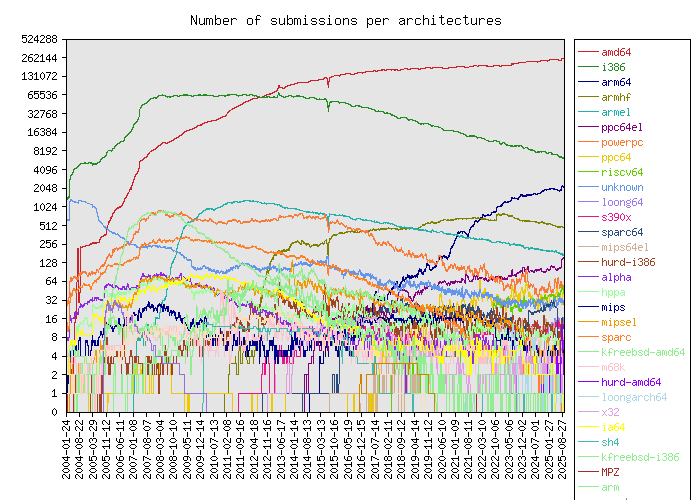

The Debian Linux distribution is one of the most widely used Linux distributions in the world. There are many more derivatives of this distribution too, like Ubuntu and Mint. One of the things Debian publishes regularly is statistics about the users that choose to share them. These statistics go as far back as 2004, which is really interesting. One of the datapoints gathered is architecture.

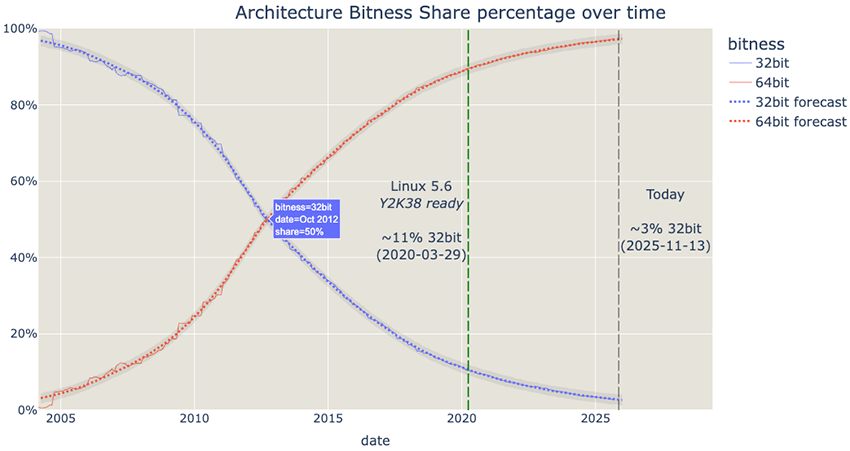

This is very useful for our problem, since it allows us to estimate how likely a system is to be running on a 32-bit architecture given how old it is. In fact, sometime around October 2012 was when the 64 bit architecture surpassed 32-bit architecture in terms of numbers:

At present day, there is still around 3% of all Debian systems running on a 32-bit architecture. If you correlate this with the date that each Apache Debian version was published, you can get a fair estimate of how many systems exposing HTTP servers are out there: around 76 000.

In fact, we know that any Linux system in general that is running on 32-bit with a kernel pre 5.6 (first launched in 2020) is vulnerable to Y2K38.

Boa Web Server

We stated previously that assessing Y2K38 systems via a web server depends on the server software and version. We described a probabilist approach to Debian linux as a proxy of how many systems are likely vulnerable, which does not translate to Boa Web Server. Boa is a small, fast, single-tasking HTTP web server written in C, created in the late 1990s with a very specific goal: serve embedded systems with extremely limited CPU, RAM, and storage. Boa was the default web UI server for embedded Linux for many years. The official distribution has also not been maintained since… 2005! It is used in routers, modems, IP cameras, DVRs / NVRs, printers, NAS, building management systems, ICS / OT HMIs, and the list goes on.

Boa almost always runs on 32-bit systems, so finding a Boa webserver exposed will most likely mean finding an underlying Y2K38 vulnerable system. There are around 500 000 of them and these are just the ones we can see connected to the Internet. Curiously, on September 18, 1999, the Y2K38 vulnerability was already acknowledged, in their Y2K compliance page :

“Boa is Year 2000 compliant. … The Unix(TM) and Unix-like systems for which Boa is designed generally store dates internally as signed 32-bit integers which contain the number of seconds since 1 January 1970, making the year 2000 irrelevant. On 32-bit computers (and 32-bit data structures, for example in file systems) one boundary to worry about is the year 2038, when that number will roll negative if treated as a signed number.“

ICS/OT

The ICS/OT space is one of the most concerning areas when it comes to Y2K38. Unlike consumer devices, which seem to be shipped with programmed obsolescence and frequently replaced, industrial control systems are meant to work for decades. Along with the fact that they control cyber physical processes and are often deployed in our critical infrastructure, this creates an additional concern. Think about this example that we already researched and documented: Automatic Fuel Gauges (ATGs). ATG systems play a role in our critical infrastructure by monitoring and managing fuel storage tanks, such as those found in everyday gas stations. These systems ensure that fuel levels are accurately tracked, leaks are detected early, and inventory is managed efficiently. Although the typical gas station comes to mind when thinking about fuel tanks, these systems also exist in other critical facilities, including military bases, hospitals, airports, emergency services, and power plants, to name a few. We’ve found many vulnerabilities in different systems in the past but last year CISA published some more that are specifically related to Y2K38: CVE-2025-55067 and CVE-2025-55068 (can be found in their respective ICSAs here and here)

Today, there are between 5 000 to 10 000 ATGs that are exposed worldwide. Most of them are suspected vulnerable to Y2K38, some have been confirmed already. These are the ones that are online and exposed. There are over 120 000 gas stations in the US alone. According to EPA, there are approximately 535 000 active tanks at approximately 192 000 facilities which are regulated by the UST program. How many of the half a million tanks have an ATG and how many are vulnerable to Y2K38? We don’t know. And that is a big problem.

Why the urgency?

The urgency is mostly about time to fix. I know, twelve years seems like a lot of time. But consider the past example of a similar effort that was previously mentioned: The Year 2000 bug. Fixing the Y2K bug was a massive global undertaking that cost hundreds of billions of dollars and spanned over 40 years of awareness, in some form, before its peak in the late 1990s. Bob Bemer is generally recognized as the earliest documented person to explicitly identify the two-digit year problem and this was in 1958. The brokerage industry began significant fixes in the 1980s to handle bond maturity dates. By 1987, the New York Stock Exchange had already spent over $20 million and hired 100 programmers dedicated to Y2K. The effort involved millions of developers and technicians worldwide. Programmers had to manually review, update, and test billions of lines of code. The panic, however, peaked in 1999, shortly after the creation of the International Y2K Cooperation Center by the UN in December 1998. There was a gigantic effort during the last couple of years leading to the year 2000 and then… nothing happened. Well, not nothing. There were still some issues here and there, but mitigations were largely a success. So much, that it was perceived that maybe the problem was unnecessarily inflated. For example, in Slovenia, the uneventfulness of Y2K was so anticlimactic that a top official was accused of exaggerating the danger and fired from his job. Ironically, its legacy is that its mitigations worked precisely because it was taken so seriously.

An understatement

Now, when I said a similar effort, this is a serious understatement. There are several reasons for that and we are going to focus on three major ones: scale, scope and status.

Scale

The main reason is the shear scale. In 1999, there were around 50 million internet connected systems. Today there are over 30 billion. That is an extraordinary increase, we are talking about more than 600 times increase in less than 30 years. There is no reason to believe that this growing trend will stop in the next decade. And that is just connected ‘stuff’. First we need to figure out what those vulnerable systems are, then we need to figure out where they are installed and how to fix them (if possible). Of course, we can’t just do this in random order, we will need to prioritise. Life supporting systems should not have the same priority of, let’s say, vending machines. But even prioritization can get tricky.

Take the example of smart TVs: we know (research undergoing) that there are a lot of smart TVs vulnerable to Y2K38. By the end of this year, it is projected that there will be 1 billion (!) smart TVs in the world. Why are they important for prioritization? Well, if they shut down in the middle of your favorite game, that is just unfortunate and annoying. But smart TVs are an information display device and are everywhere, from your living room to your hospital, from your company meeting room to your airport. What if a display stops in the middle of a surgery or a military operation? The device or system itself and how it fails is not enough to decide prioritization, it has to be analyzed in its usage context and the potential cascading effects.

Scope

Not only is the scale important but also the type of systems more prone to fail: those that use 32-bit architecture. 32-bit architecture is no mere relic of the past, it is still a specialized, high-performance standard that remains the cornerstone of embedded computing, the very ‘stuff’ that runs our world. Its usage dominates the "invisible" world of microcontrollers (MCUs) in critical sectors like automotive, industrial, building management systems and IoT. 32-bit architectures are still projected to hold a staggering 44% market share in 2026. These systems continue to favor 32-bit designs because they offer toolchains, efficiency, low cost, and a decades-long history of proven reliability in highly regulated fields like aerospace and medicine. We are still producing vulnerable systems today and bury them in our critical infrastructure! This is, besides scale, another reason similar effort was an understatement.

Imagine that we need to physically replace a big percentage of existing ATGs, like 50 000. An ATG replacement involves assessing the existing system, securing permits, and scheduling tank downtime, then backing up and removing the old console, probes, and sensors as needed. The new ATG is installed, wired, configured, calibrated, tested for leak detection compliance, inspected by the authority having jurisdiction, and only then returned to service. This takes time and requires specialized technicians, of which there are a finite supply. It also costs money, a lot of money. A rough estimate places this thought experiment exercise at a combined cost of ~$1-1.8 Billion USD, and would require around 3-6 years, with 4-5 years being the most realistic expectation given today’s technician, regulatory, and operational constraints. What about factory floors, how many systems need to be replaced there? And in power plants? Cars? Airplanes? Boats? Submarines? We don’t know and not knowing is a risk we cannot be willing to take. What we know is that the architecture we trusted most to handle complex, critical, real-time tasks is now at the heart of one of the most challenging planetary technological crisis.

Status

Lastly I would like to mention something that is not usually addressed. We are all assuming we have 12 years before this problem starts to manifest itself. We don’t. It will naturally start to occur sooner as we approach that date, as processes that depend on long time calculations start to fail. But there is a greater subtle threat: manipulating time is not extraordinarily complicated. NTP, the protocol used to synchronize time most systems use, is not a secure protocol. It is easy to spoof or manipulate. GPS signals, used by some NTP servers, cars and other field devices as a source of truth for time, can be easily and cheaply falsified too. Some systems allow for time to be changed remotely in an unauthenticated way.

What I’m saying is that this can be weaponized by threat actors today. Not in 12 years… today! We have been conducting tests at our ICS lab and it is definitely possible to manipulate both NTP and GPS to induce Y2K38 related vulnerabilities, crash systems, corrupt logs, deny access to devices and other undesired effects. And this is why Y2K38 is a vulnerability and not a bug. If an attacker has the ability to manipulate time in a device and affect the security CIA triad (confidentiality, integrity and availability), this is a vulnerability by definition. There are also advantages to looking at this as a vulnerability and not a bug. A bug has a JIRA ticket that gets lost in the ticket backlog. A vulnerability has a different status, it should have a CVE and we can leverage several frameworks (CVSS, EPSS, SSVC, <insert favorite one>) that allow for stakeholders to have better communication, understanding and prioritization.

Going forward

I hope by now that it is clear that the challenge we face ahead is a gigantic endeavor. There will be no single patch and no easy fix. Nobody, no company and not even no country can fix this single handedly. Awareness, cooperation, community and information sharing will prove paramount in our success or failure to handle this at scale.

You can’t fix what you don’t know. So this seems like a good first step: to identify which systems are potentially vulnerable and where they are. And that is exactly what we at Bitsight are doing. We are developing tools and techniques to aid in this effort. We are gaining understanding of this problem at planetary scale. We are sharing our knowledge and results at security conferences and many other different venues. What about you? What will be your role?

This is a global challenge and requires an “all hands on deck” approach. If you are curious or working on this problem, we welcome you to engage in an open dialogue to better understand Y2K38 identification, remediation and risk analysis. By sharing knowledge and working together, we can accelerate the solutions we all need.

Time is critical infrastructure. Proper time keeping and handling must not be underestimated. Without time, there is no trust, no security and no safety.