Published on January 20, 2026 3:35 PM GMT

Epistemic status: This post is a synthesis of ideas that are, in my experience, widespread among researchers at frontier labs and in mechanistic interpretability, but rarely written down comprehensively in one place - different communities tend to know different pieces of evidence. The core hypothesis - that deep learning is performing something like tractable program synthesis - is not original to me (even to me, the ideas are ~3 years old), and I suspect it has been arrived at independently many times. (See the appendix on related work).

This is also far from finished research - more a snapshot of a hypothesis that seems increasingly hard to avoid, and a case for why formalization is worth pursuing. I discuss the key b…

Published on January 20, 2026 3:35 PM GMT

Epistemic status: This post is a synthesis of ideas that are, in my experience, widespread among researchers at frontier labs and in mechanistic interpretability, but rarely written down comprehensively in one place - different communities tend to know different pieces of evidence. The core hypothesis - that deep learning is performing something like tractable program synthesis - is not original to me (even to me, the ideas are ~3 years old), and I suspect it has been arrived at independently many times. (See the appendix on related work).

This is also far from finished research - more a snapshot of a hypothesis that seems increasingly hard to avoid, and a case for why formalization is worth pursuing. I discuss the key barriers and how tools like singular learning theory might address them towards the end of the post.

Thanks to Dan Murfet, Jesse Hoogland, Max Hennick, and Rumi Salazar for feedback on this post.

Sam Altman: Why does unsupervised learning work?

Dan Selsam: Compression. So, the ideal intelligence is called Solomonoff induction…[1]

The central hypothesis of this post is that deep learning succeeds because it’s performing a tractable form of program synthesis - searching for simple, compositional algorithms that explain the data. If correct, this would reframe deep learning’s success as an instance of something we understand in principle, while pointing toward what we would need to formalize to make the connection rigorous.

I first review the theoretical ideal of Solomonoff induction and the empirical surprise of deep learning’s success. Next, mechanistic interpretability provides direct evidence that networks learn algorithm-like structures; I examine the cases of grokking and vision circuits in detail. Broader patterns provide indirect support: how networks evade the curse of dimensionality, generalize despite overparameterization, and converge on similar representations. Finally, I discuss what formalization would require, why it’s hard, and the path forward it suggests.

Background

Whether we are a detective trying to catch a thief, a scientist trying to discover a new physical law, or a businessman attempting to understand a recent change in demand, we are all in the process of collecting information and trying to infer the underlying causes.

-Shane Legg[2]

Early in childhood, human babies learn object permanence - that unseen objects nevertheless persist even when not directly observed. In doing so, their world becomes a little less confusing: it is no longer surprising that their mother appears and disappears by putting hands in front of her face. They move from raw sensory perception towards interpreting their observations as coming from an external world: a coherent, self-consistent process which determines what they see, feel, and hear.

As we grow older, we refine this model of the world. We learn that fire hurts when touched; later, that one can create fire with wood and matches; eventually, that fire is a chemical reaction involving fuel and oxygen. At each stage, the world becomes less magical and more predictable. We are no longer surprised when a stove burns us or when water extinguishes a flame, because we have learned the underlying process that governs their behavior.

This process of learning only works because the world we inhabit, for all its apparent complexity, is not random. It is governed by consistent, discoverable rules. If dropping a glass causes it to shatter on Tuesday, it will do the same on Wednesday. If one pushes a ball off the top of a hill, it will roll down, at a rate that any high school physics student could predict. Through our observations, we implicitly reverse-engineer these rules.

This idea - that the physical world is fundamentally predictable and rule-based - has a formal name in computer science: the physical Church-Turing thesis. Precisely, it states that any physical process can be simulated to arbitrary accuracy by a Turing machine. Anything from a star collapsing to a neuron firing, can, in principle, be described by an algorithm and simulated on a computer.

From this perspective, one can formalize this notion of “building a world model by reverse-engineering rules from what we can see.” We can operationalize this as a form of program synthesis: from observations, attempting to reconstruct some approximation of the “true” program that generated those observations. Assuming the physical Church-Turing thesis, such a learning algorithm would be “universal,” able to eventually represent and predict any real-world process.

But this immediately raises a new problem. For any set of observations, there are infinitely many programs that could have produced them. How do we choose? The answer is one of the oldest principles in science: Occam’s razor. We should prefer the simplest explanation.

In the 1960s, Ray Solomonoff formalized this idea into a theory of universal induction which we now call Solomonoff induction. He defined the “simplicity” of a hypothesis as the length of the shortest program that can describe it (a concept known as Kolmogorov complexity). An ideal Bayesian learner, according to Solomonoff, should prefer hypotheses (programs) that are short over ones that are long. This learner can, in theory, learn anything that is computable, because it searches the space of all possible programs, using simplicity as its guide to navigate the infinite search space and generalize correctly.

The invention of Solomonoff induction began[3] a rich and productive subfield of computer science, algorithmic information theory, which persists to this day. Solomonoff induction is still widely viewed as the ideal or optimal self-supervised learning algorithm, which one can prove formally under some assumptions[4]. These ideas (or extensions of them like AIXI) were influential for early deep learning thinkers like Jürgen Schmidhuber and Shane Legg, and shaped a line of ideas attempting to theoretically predict how smarter-than-human machine intelligence might behave, especially within AI safety.

Unfortunately, despite its mathematical beauty, Solomonoff induction is completely intractable. Vanilla Solomonoff induction is incomputable, and even approximate versions like speed induction are exponentially slow[5]. Theoretical interest in it as a “platonic ideal of learning” remains to this day, but practical artificial intelligence has long since moved on, assuming it to be hopelessly unfeasible.

Meanwhile, neural networks were producing results that nobody had anticipated.

This was not the usual pace of scientific progress, where incremental advances accumulate and experts see breakthroughs coming. In 2016, most Go researchers thought human-level play was decades away; AlphaGo arrived that year. Protein folding had resisted fifty years of careful work; AlphaFold essentially solved it[6] over a single competition cycle. Large language models began writing code, solving competition math problems, and engaging in apparent reasoning - capabilities that emerged from next-token prediction without ever being explicitly specified in the loss function. At each stage, domain experts (not just outsiders!) were caught off guard. If we understood what was happening, we would have predicted it. We did not.

The field’s response was pragmatic: scale the methods that work, stop trying to understand why they work. This attitude was partly earned. For decades, hand-engineered systems encoding human knowledge about vision or language had lost to generic architectures trained on data. Human intuitions about what mattered kept being wrong. But the pragmatic stance hardened into something stronger - a tacit assumption that trained networks were intrinsically opaque, that asking what the weights meant was a category error.

At first glance, this assumption seemed to have some theoretical basis. If neural networks were best understood as “just curve-fitting” function approximators, then there was no obvious reason to expect the learned parameters to mean anything in particular. They were solutions to an optimization problem, not representations. And when researchers did look inside, they found dense matrices of floating-point numbers with no obvious organization.

But a lens that predicts opacity makes the same prediction whether structure is absent or merely invisible. Some researchers kept looking.

Looking inside

Grokking

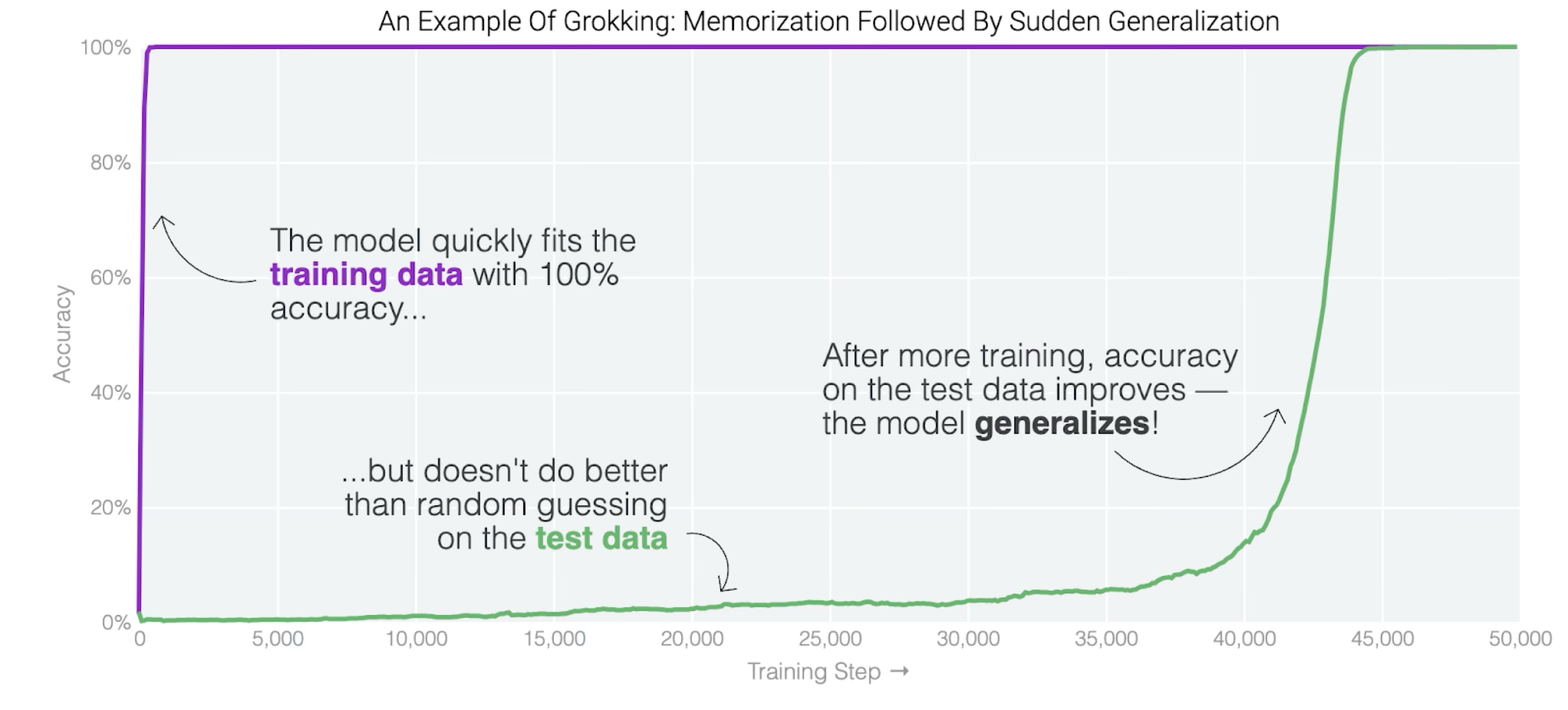

Power et al. (2022) train a small transformer on modular addition: given two numbers, output their sum mod 113. Only a fraction of the possible input pairs are used for training - say, 30% - with the rest held out for testing.

The network memorizes the training pairs quickly, getting them all correct. But on pairs it hasn’t seen, it does no better than chance. This is unsurprising: with enough parameters, a network can simply store input-output associations without extracting any rule. And stored associations don’t help you with new inputs.

Here’s what’s unexpected. If you keep training, despite the training loss already nearly as low as it can go, the network eventually starts getting the held-out pairs right too. Not gradually, either: test performance jumps from chance to near perfect over only a few thousand training steps.

So something has changed inside the network. But what? It was already fitting the training data; the data didn’t change. There’s no external signal that could have triggered the shift.

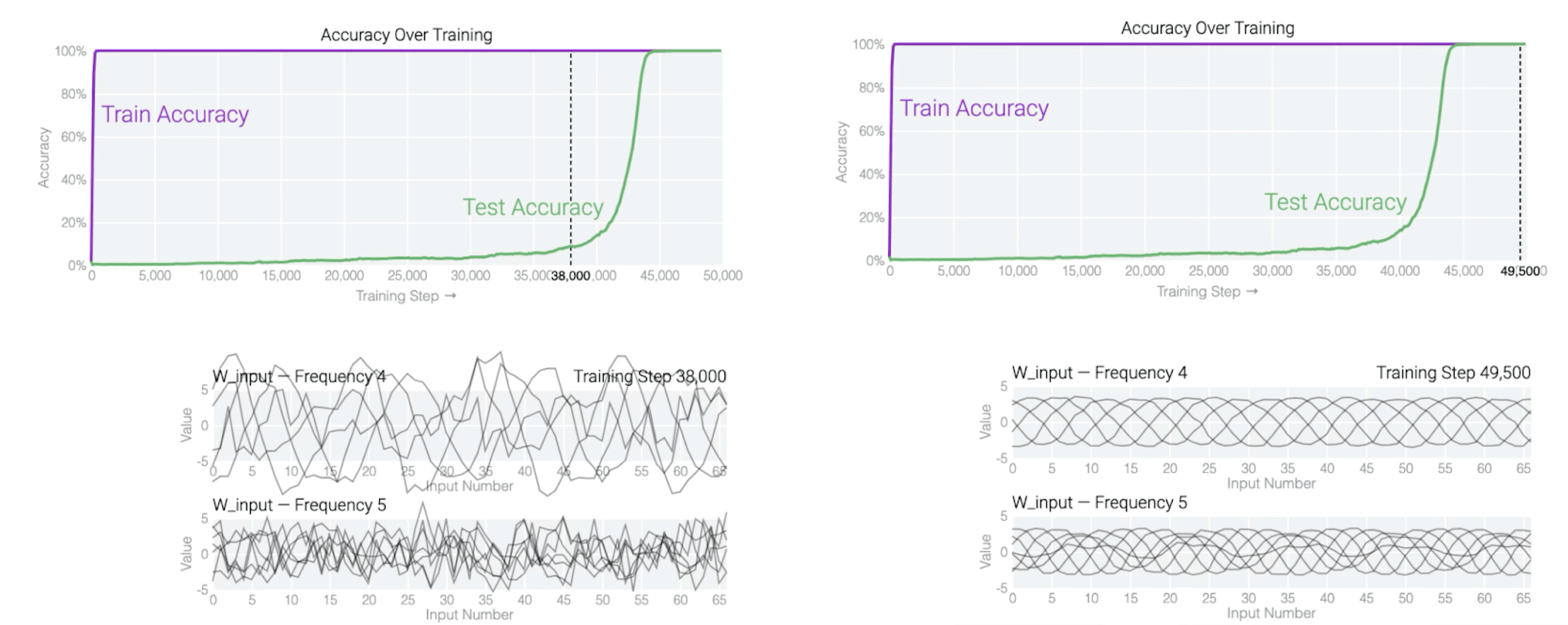

One way to investigate is to look at the weights themselves. We can do this at multiple checkpoints over training and ask: does something change in the weights around the time generalization begins?

It does. The weights early in training, during the memorization phase, don’t have much structure when you analyze them. Later, they do. Specifically, if we look at the embedding matrix, we find that it’s mapping numbers to particular locations on a circle. The number 0 maps to one position, 1 maps to a position slightly rotated from that, and so on, wrapping around. More precisely: the embedding of each number contains sine and cosine values at a small set of specific frequencies.

This structure is absent early in training. It emerges as training continues, and it emerges around the same time that generalization begins.

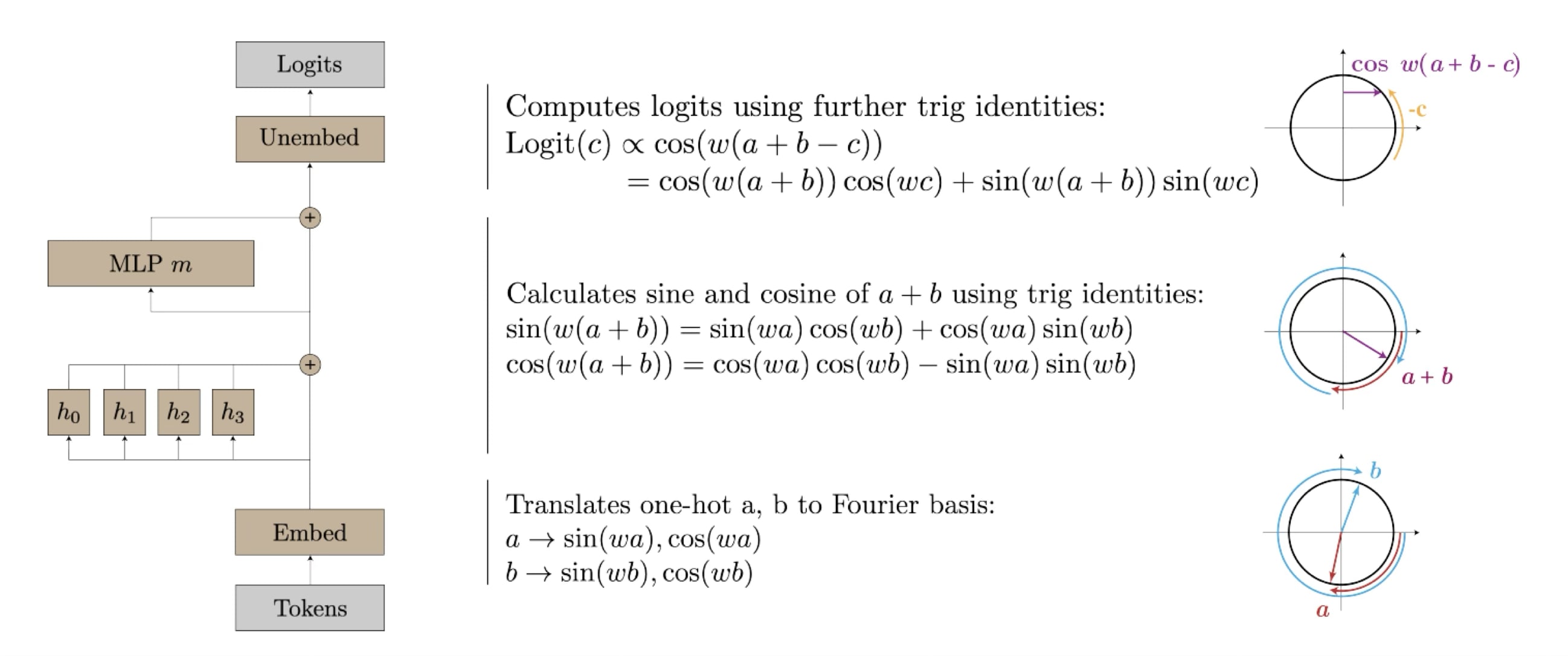

So what is this structure doing? Following it through the network reveals something unexpected: the network has learned an algorithm for modular addition based on trigonometry.[7]

The algorithm exploits how angles add. If you represent a number as a position on a circle, then adding two numbers corresponds to adding their angles. The network’s embedding layer does this representation. Its middle layers then combine the sine and cosine values of the two inputs using trigonometric identities. These operations are implemented in the weights of the attention and MLP layers: one can read off coefficients that correspond to the terms in these identities.

Finally, the network needs to convert back to a discrete answer. It does this by checking, for each possible output , how well matches the sum it computed. Specifically, the logit for output depends on . This quantity is maximized when equals - the correct answer. At that point the cosines at different frequencies all equal 1 and add constructively. For wrong answers, they point in different directions and cancel.

This isn’t a loose interpretive gloss. Each piece - the circular embedding, the trig identities, the interference pattern - is concretely present in the weights and can be verified by ablations.

So here’s the picture that emerges. During the memorization phase, the network solves the task some other way - presumably something like a lookup table distributed across its parameters. It fits the training data, but the solution doesn’t extend. Then, over continued training, a different solution forms: this trigonometric algorithm. As the algorithm assembles, generalization happens. The two are not merely correlated; tracing the structure in the weights and the performance on held-out data, they move together.

What should we make of this? Here’s one reading: the difference between a network that memorizes and a network that generalizes is not just quantitative, but qualitative. The two networks have learned different kinds of things. One has stored associations. The other has found a method - a mechanistic procedure that happens to work on inputs beyond those it was trained on, because it captures something about the structure of the problem.

This is a single example, and a toy one. But it raises a question worth taking seriously. When networks generalize, is it because they’ve found something like an algorithm? And if so, what does that tell us about what deep learning is actually doing?

It’s worth noting what was and wasn’t in the training data. The data contained input-output pairs: “32 and 41 gives 73,” and so on. It contained nothing about how to compute them. The network arrived at a method on its own.

And both solutions - the lookup table and the trigonometric algorithm - fit the training data equally well. The network’s loss was already near minimal during the memorization phase. Whatever caused it to keep searching, to eventually settle on the generalizing algorithm instead, it wasn’t that the generalizing algorithm fit the data better. It was something else - some property of the learning process that favored one kind of solution over another.

The generalizing algorithm is, in a sense, simpler. It compresses what would otherwise be thousands of stored associations into a compact procedure. Whether that’s the right way to think about what happened here - whether “simplicity” is really what the training process favors - is not obvious. But something made the network prefer a mechanistic solution that generalized over one that didn’t, and it wasn’t the training data alone.[8]

Vision circuits

Grokking is a controlled setting - a small network, a simple task, designed to be fully interpretable. Does the same kind of structure appear in realistic models solving realistic problems?

Olah et al. (2020) study InceptionV1, an image classification network trained on ImageNet - a dataset of over a million photographs labeled with object categories. The network takes in an image and outputs a probability distribution over a thousand possible labels: “car,” “dog,” “coffee mug,” and so on. Can we understand this more realistic setting?

A natural starting point is to ask what individual neurons are doing. Suppose we take a neuron somewhere in the network. We can find images that make it activate strongly by either searching through a dataset or optimizing an input to maximize activation. If we collect images that strongly activate a given neuron, do they have anything in common?

In early layers, they do, and the patterns we find are simple. Neurons in the first few layers respond to edges at particular orientations, small patches of texture, transitions between colors. Different neurons respond to different orientations or textures, but many are selective for something visually recognizable.

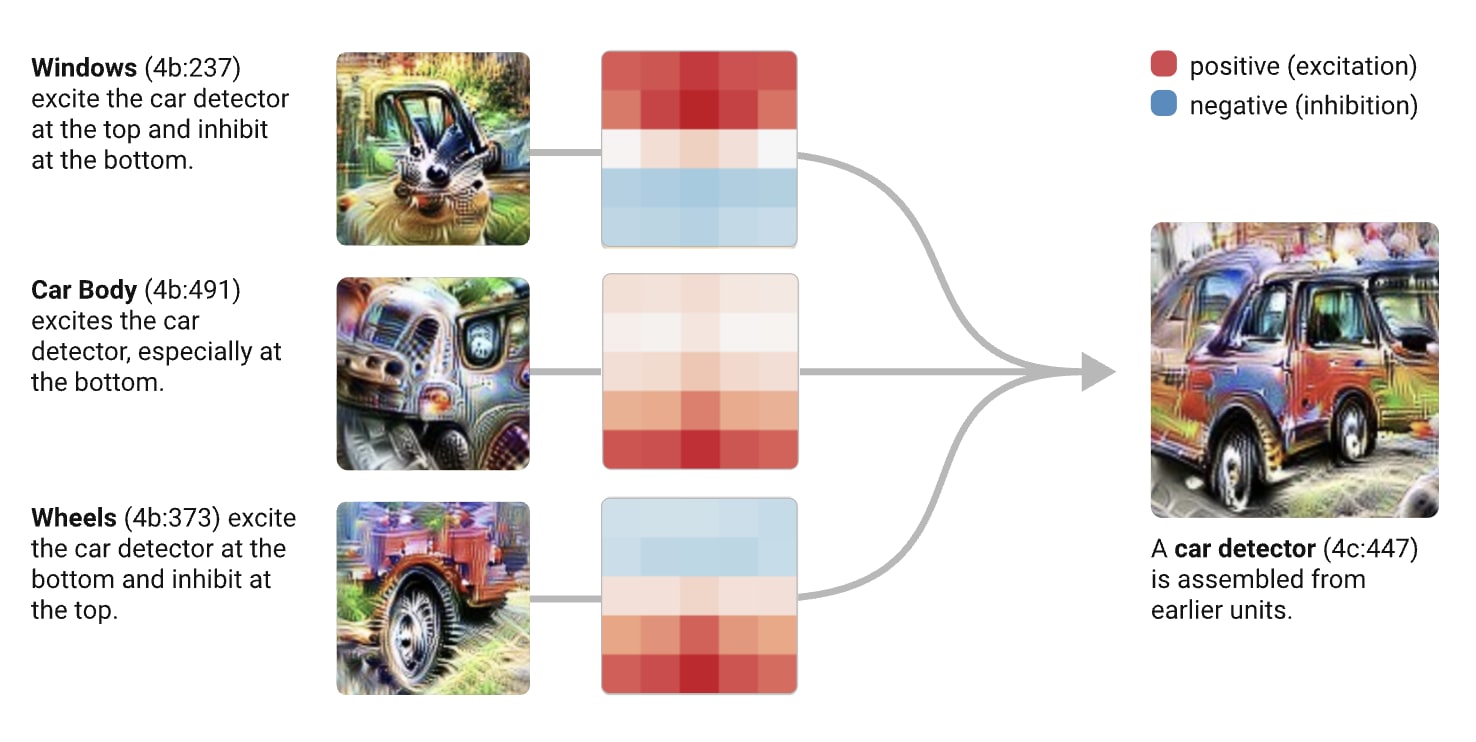

In later layers, the patterns we find become more complex. Neurons respond to curves, corners, or repeating patterns. Deeper still, neurons respond to things like eyes, wheels, or windows - object parts rather than geometric primitives.

This already suggests a hierarchy: simple features early, complex features later. But the more striking finding is about how the complex features are built.

Olah et al. do not just visualize what neurons respond to. They trace the connections between layers - examining the weights that connect one layer’s neurons to the next, identifying which earlier features contribute to which later ones. What they find is that later features are composed from earlier ones in interpretable ways.

There is, for instance, a neuron in InceptionV1 that we identify as responding to dog heads. If we trace its inputs by looking at which neurons from the previous layer connect to it with strong weights, we find it receives input from neurons that detect eyes, snout, fur, and tongue. The dog head detector is built from the outputs of simpler detectors. It is not detecting dog heads from scratch; it is checking whether the right combination of simpler features is present in the right spatial arrangement.

We find the same pattern throughout the network. A neuron that detects car windows is connected to neurons that detect rectangular shapes with reflective textures. A neuron that detects car bodies is connected to neurons that detect smooth, curved surfaces. And a neuron that detects cars as a whole is connected to neurons that detect wheels, windows, and car bodies, arranged in the spatial configuration we would expect for a car.

Olah et al. call these pathways “circuits,” and the term is meaningful. The structure is genuinely circuit-like: there are inputs, intermediate computations, and outputs, connected by weighted edges that determine how features combine. In their words: “You can literally read meaningful algorithms off of the weights.”

And the components are reused. The same edge detectors that contribute to wheel detection also contribute to face detection, to building detection, to many other things. The network has not built separate feature sets for each of the thousand categories it recognizes. It has built a shared vocabulary of parts - edges, textures, curves, object components, etc - and combines them differently for different recognition tasks.

We might find this structure reminiscent of something. A Boolean circuit is a composition of simple gates - each taking a few bits as input, outputting one bit - wired together to compute something