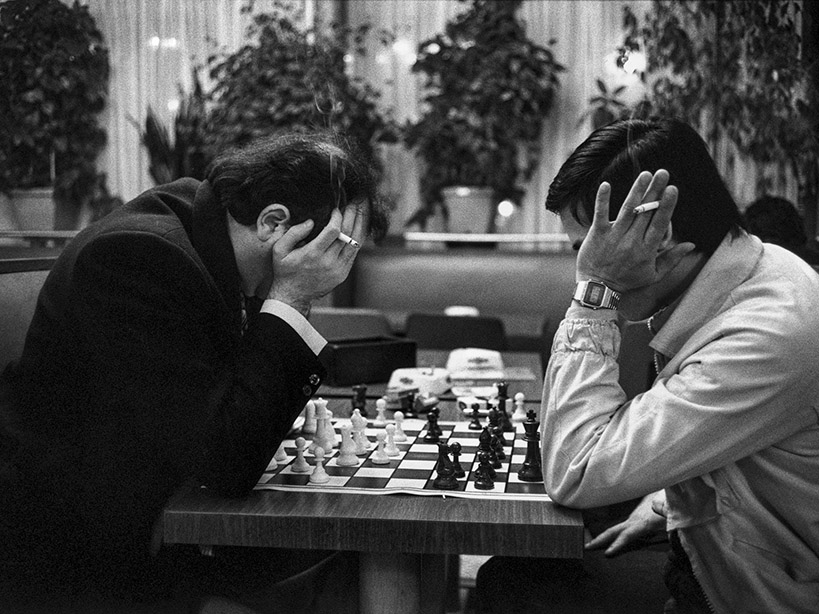

Photo by Richard Kalvar/ Magnum Photos

Photo by Richard Kalvar/ Magnum Photos

In Stefan Zweig’s 1941 novella The Royal Game, the mysterious Dr B explains his obsession with chess. Imprisoned by the Gestapo, Dr B steals a chess book. He imagines chess games, splitting himself into both opponents. He watches eagerly as one “brain” makes a move, counters with his other “brain”, and so on. The situation is “a logical absurdity”, writes Zweig; playing chess against yourself is “as much of a paradox as jumping over your own shadow”. Eventually poor Dr B is found screaming in his cell.

Zweig’s story came to mind as I read an article about how large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT and Grok, learned to play chess. While LLMs aren’t expressly design…

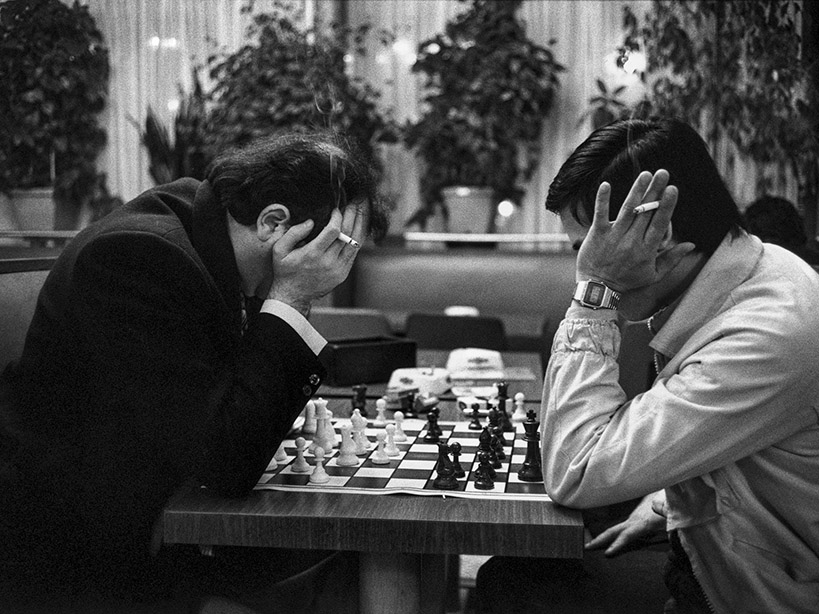

Photo by Richard Kalvar/ Magnum Photos

Photo by Richard Kalvar/ Magnum Photos

In Stefan Zweig’s 1941 novella The Royal Game, the mysterious Dr B explains his obsession with chess. Imprisoned by the Gestapo, Dr B steals a chess book. He imagines chess games, splitting himself into both opponents. He watches eagerly as one “brain” makes a move, counters with his other “brain”, and so on. The situation is “a logical absurdity”, writes Zweig; playing chess against yourself is “as much of a paradox as jumping over your own shadow”. Eventually poor Dr B is found screaming in his cell.

Zweig’s story came to mind as I read an article about how large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT and Grok, learned to play chess. While LLMs aren’t expressly designed to play games, unlike Deep Blue or Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo, they are infinitely better at chess than I’ll ever be, but they sometimes make illegal moves. In August 2025, the world’s first LLM Chess Tournament took place. OpenAI’s o3 played Grok 4 in the final; grandmasters Magnus Carlsen and David Howell provided commentary. “Oh my God… No… No… Come on…” said Carlsen, as Grok made a blunder. “Poor Grok,” said Howell. OpenAI took the title.

Two-player games are traditionally a battle between two minds, a war of opposites. Two sets of pieces. Two sides of the board. Karpov vs Kasparov; Fischer vs Spassky. When Lee Sedol, world champion of the ancient strategy board game Go, was defeated by AlphaGo, he quit the game altogether: “There is an entity that cannot be defeated,” he said. LLMs don’t have minds, but their accelerated use of predictive text gives an eerie impression of “thought” and poses deep questions about consciousness and language, formal constraints and formless reality. Such questions are fundamental to games, and also fundamental to novels, which have their own rules. Many authors have been inspired to write novels about two-player games such as chess and Go, or have created their own games, exploring questions about what it means to be a finite mortal, winning and losing, playing again.

Often, the minds of fictional players are dangerously obsessed, teetering on the brink of madness. In The Defense (1930), Vladimir Nabokov places the reader into the fixated mind of the protagonist, Luzhin, as he flounders in “the abysmal depths”: “for what else exists in the world besides chess?” In Walter Tevis’s *The Queen’s Gambit *(1983), Beth Harmon is the tormented player who is struggling against both grandmasters and a more general prejudice towards girls that play chess. Like Dr B, Harmon experiences mesmerising chess-hallucinations, finding herself “poised over an abyss, sustained there only by the bizarre mental equipment that had fitted her for this elegant and deadly game”. Ah Cheng’s *The Chess Master *(1984) also presents the struggles of a player of Xiangqi, or Chinese chess, where the obsession with the game is entwined with a quest for existential serenity.

New year, new read. Save 40% off an annual subscription this January.

The game is rarely just a game. As Paolo Maurensig writes in The Lüneburg Variation (1993): “Chess was born in bloodshed.” Like Zweig and others Maurensig’s chess play is set against the carnage of the Second World War. In Kurt Vonnegut’s short story “All the King’s Horses” (circa 1951), an American soldier is captured by communist forces. He must play chess to survive, with real humans as playing pieces and real death as the consequence of being “taken”. The same grim inevitability hangs over JG Ballard’s story “End Game” (1963), in which a man is condemned to death and forced to hang out with his executioner, playing chess to pass the time. No one has any choice, even as their minds race through other possibilities, other rules. No surprise that both Beckett and Kafka were fans of chess.

Who decides the rules of the game? What happens if we try to evade or challenge them? Questions of free will and determinism course through brilliant philosophical games-fictions by Philip K Dick’s The Game-Players of Titan (1963), Iain M Banks’s The Player of Games (1988) and Joanna Russ’s “A Game of Vlet” (1974). In all three, the games are fictional. Dick’s “Bluff” is played in a world of telepaths, where minds are no longer discrete. Russ’s “Vlet” is magical, like a fever dream of chess, and brings about a revolution. In Hermann Hesse’s *The Glass Bead Game *(1943), another invented game “has no real beginning, rather, it has always been”. It seems to combine mathematics, music, art, philosophy and the “same eternal idea” that has underlain “every effort toward reconciliation between science and art or science and religion”. Hesse draws his omni-game into a further idea of spiritual harmony: in the alternation between binaries, Heaven and Earth, Ying and Yang, “holiness is forever being created”.

The above line appears in Liza Dalby’s lucid introduction to The Master of Go (1954), by Yasunari Kawabata: a beautiful, fictionalised account of a 1938 Go tournament in which a veteran master, Honinbo Shūsai, lost to a new challenger, Minoru Kitani. Kawabata attended the tournament as a journalist. Dalby identifies several parallels between Kawabata and Hesse: both wrote their novels during the Second World War and both were inspired by ideas about harmony and the reconciliation of opposites. “There can be no world of the Buddha without the world of the devil,” said Kawabata. “And the world of the devil is the world difficult of entry. It is not for the faint of heart.”

If only reality were more playful, less fraught with danger. If only the small games of humans weren’t menaced by the arbitrary rules of tyrants and liars. Such themes also emerge in the Go-references of contemporary novels such as David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (2010) and Scarlett Thomas’s PopCo (2004). Both works explore the gaps in rule-based systems, the myriad ways in which reality may exceed formal constraints. Mitchell and Thomas also nod to another subcategory of games-fiction in which authors take game-rules as organising precepts. For example, Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871); Georges Perec’s *Life: A User’s Manual *(1978); Enrique Vila-Matas’s *Mac and His Problem *(2019) – all involve chess.

In his fictions, Italo Calvino also deploys game structures and an idea of chess as a metaphor for the human mind. In his prescient 1967 essay “Cybernetics and Ghosts”, Calvino suggests that literary machines will soon replace writers, because they will be able to hammer out novels while beating us at chess. Yet the real game, for Calvino, as for all the authors I’ve listed, is the game of life: the unpredictable formulations, moments of fleeting triumph, the inevitable defeat. Another game entirely. Language isn’t enough to express even five minutes of consciousness. Try your best but you are, as Kafka wrote, “the pawn of a pawn, a piece which doesn’t even exist, which isn’t even in the game”. Yet you’re still trying to play.

One last thing: I’ve had to apply a few rules to this article. I’ve had to omit many great novels about virtual reality games, about games with more than two players. For this reason, I didn’t write about Chris Van Allsburg’s Jumanji (two to four players), nor about William Sleator’s Interstellar Pig, which has three players (actually aliens) plus one human (who must play the game to save the world). Still, I’ve mentioned them now, so I guess I’ve broken my own rules.

[Further reading: The alt-right’s fantasy Britain]

Related