- 06 Dec, 2025 *

What is a homelab? A homelab is a home sandbox where IT professionals or just enthusiasts have fun and experiment with various software and hardware. This can serve completely different purposes: from a simple self-hosting services like Nextcloud to studying and preparing for an exam for some certification.

I had a great homelab, but it took up a lot of space and consumed a lot of electricity. After moving to another country, it stood idle, and I was only able to take it with me thanks to a miracle and the existence of a land border. And now I need to move again, to another country. This time, alas, by plane. I had to sell quite a lot of hardware. Then I realized that this move was unlikely to be my l…

- 06 Dec, 2025 *

What is a homelab? A homelab is a home sandbox where IT professionals or just enthusiasts have fun and experiment with various software and hardware. This can serve completely different purposes: from a simple self-hosting services like Nextcloud to studying and preparing for an exam for some certification.

I had a great homelab, but it took up a lot of space and consumed a lot of electricity. After moving to another country, it stood idle, and I was only able to take it with me thanks to a miracle and the existence of a land border. And now I need to move again, to another country. This time, alas, by plane. I had to sell quite a lot of hardware. Then I realized that this move was unlikely to be my last, and I wanted to do everything properly and write a series of articles about it.

Disclaimer: There are millions of ways to set up a homelab. That’s what makes it so great: no two homelabs are alike. This series of posts doesn’t claim to be the only definitive truth; it’s simply my vision of my homelab. In general, I’ll write more about planning, architecture, and adventures. Of course, I’ll periodically provide snippets and post some projects on GitHub/GitLab, but this series of articles won’t be a step-by-step guide. It’s something between a guide and fiction. In any case, you will need some prior knowledge or your own research to follow along with me, otherwise it will be extremely difficult for you to maintain your lab. But if you have any questions, feel free to ask them in the comments. Suggestions, constructive criticism, and other feedback are also welcome.

Requirements for a new homelab

Here is a rough list of my requirements for my next homelab:

- First and foremost, the homelab must be flexible and modular. Right now, I need something compact in case I move. One day, I may settle in one place, and then the homelab can grow in size, but it should still be possible to downsize again. And in general, requirements may change along the way. Hence the conclusion: the lab must be modular, and the modules must be relatively compact.

- Ideally, the main hardware should be transportable in one flight in my luggage. This’s so that I can be in a new place with my homelab (at least partially functional) right away, or fly back for my homelab a second time. Of course, I hope to move by land, but life doesn’t always ask what I want.

- The homelab should also be fun and interesting from a software and hardware point of view, and only then should it be efficient. That’s why I want a HA cluster and software that is closer to a typical production.

- I’m not a network engineer, but I’m occasionally interested in playing with the network, and I want huge bandwidth.

And here’s how I think it can all be solved:

- I’ve sold most of my old hardware, keeping mainly the network and drives. New hardware, at least the main devices (where the most critical services are located), must be extremely compact so that the modules are easy to transport. Ideally, they should be USFF, such as the Lenovo P3 Tiny or Dell OptiPlex. Since the main hardware will be compact, the main type of storage will be NVMe SSD. However, this does not rule out the possibility that I may later want something larger, such as an HDD or GPU server. This’s fine if no important services, such as Vaultwarden or Nextcloud, are tied to it.

- I can start with a single-node implementation. Multi-node configurations aren’t very suitable for compact solutions, even when using USFF PCs. In terms of hardware, I’m inclined towards the Minisforum MS-A2. It’s a truly compact PC with impressive capabilities. It can accommodate two 22110 NVMe M.2 drives and one U.2 7mm drive (or another 2280 M.2 drive instead). It also has up to 96 GB of DDR5 SO-DIMM RAM officially and up to 128 GB unofficially. There’s one PCIe x16 (logically x8) with support for bifurcation (splitting lines into separate devices). This means that you can add two more NVMe drives or install another good network card — another one, because out of the box there is already an Intel X710 with two SFP+ connectors (10 Gbps fiber optic each) and two other network cards with 2.5 Gbps 8P8C connectors each. The CPU is an AMD Ryzen 9 9955HX. Long story short: lots of power, excellent I/O. Perfect. Then I can buy more of the same and build a full-fledged cluster. The downside is Minisforum’s shitty support. People on the internet say that it’s very difficult to return a defective product, and there have been virtually no UEFI updates since release. I’d be happy to look at something else, but I haven’t found any alternatives with similar I/O capabilities. The closest thing is the Lenovo Thinkcentre Tiny with a substantial set of modifications, but it’s still not quite the same.

- A more effective and practical solution would be something single-node with ZFS/Btrfs, podman containers, and maybe even some management software like Portainer. But that’s not as interesting to me. So, in terms of software, the choice falls on OKD (OpenShift) — I’m interested in tinkering with Kubernetes. Let’s start with using SNO, LVM for local storage (RWO) and NooBaa or Garage as S3 server. When there will be several nodes, I plan to use Rook Ceph for cluster storage (RWX) and S3. Additionally, I’ll try to adhere to IaC and DRY wherever possible and appropriate, and to be closer to the cattle approach instead of pet. If there were a lot of unfamiliar terms here, don’t worry: in the following posts, we’ll take a closer look at these technologies, and everything will become clearer.

- Network between nodes — 2 aggregated SFP+ (luckily they’re available in MS-A2). And also 2 SFP+ for the internal Ceph network, when it’s deployed. That is, 20 Gbps for each network. Yes, I’m crazy. So what? The internal Ceph network is mainly needed to improve replication and recovery performance, and it’s also closer to a real setup and therefore more interesting. Two SFP+ ports are easy to add, and suitable Intel XL710 cards are available on Amazon. I plan to connect all of this to a Mikrotik CRS326-24S+2Q+RM. 24 SFP+ ports will allow me to connect up to six nodes. And two QSFP+ ports will be useful for potential network expansion, but more on that later.

The focus on fast networking and modularity led me to one idea. Essentially, I am creating a container/modular data center[1], only much smaller, homemade and made of sticks and stones. It’s like building railway models: miniature and toy-like, but the model as a whole resembles its reference. There is one problem — I have no idea how a data center actually works: I didn’t design or build them. But I have a rough understanding. I hope that will be enough for a homemade version.

Long-term homelab development plan

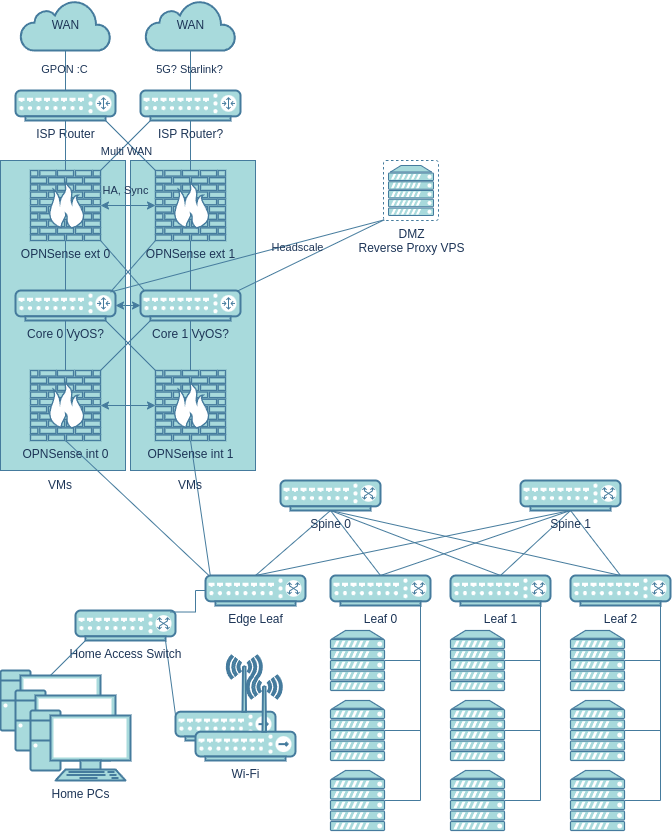

Let’s try to sketch out a possible network diagram for the final version of the home data center. The road to it will be long: a homelab is a never-ending process, and plans are always changing. But I need to know what I want to achieve in order to choose the right hardware and select and configure the software.

So, here’s the endgame network and homelab setup:

- It all starts with Multi WAN, which isn’t really necessary, and it’s not clear yet what to build it on: the apartment building where I live is connected to only one provider.

- Next come the crappy routers from the provider, and that’s quite realistic, alas. The current ISP has installed a router that cannot be converted to a bridge (most of the settings are locked, and I couldn’t get root access), and it’s connected to the provider via GPON. In other words, there’s no getting rid of this device. Bloody extra NAT.

- Next is the local network edge in the form of a virtualized sandwich. The external firewall filters potential threats from outside (to be honest, in the current setup with CGNAT and NAT on the provider’s router, there will be minimal threats from outside). Next is the network core, probably on VyOS. Or maybe on bare Linux, I don’t know. VyOS looks interesting, but they are clearly messing around with LTS builds for the community, which I don’t really like. The main thing for me is that the core runs full-fledged Linux: that way, I’ll have really fast NAT, routing, and crazy expandability. The sandwich is topped off with another OPNSense, now filtering traffic from the reverse proxy and between local devices in different subnets/VLANs. All this is on two separate boxes with virtualization, the second one backing up the first. Why virtualize? It’s more convenient to conduct experiments without breaking the network — snapshots and cloning provide an extra layer of safety. Plus, instead of three devices, we have one. The same Minisforum MS-A2 fits perfectly here.

- The home part is simpler and not as interesting. OpenWrt will be installed on the Wi-Fi access points. The access switch is connected via the homelab segment (to save ports on the VM boxes).

- And now we come to the homelab part. It’s an almost typical 3-stage Spine-Leaf factory with a 3:1 oversubscription ratio. Edge lets some home traffic through, but only through VLANs and strictly upstream. Starting with Edge, all switches must be capable of hardware L3 offloading. There will only be L3 in the underlay, because ECMP is needed for full utilization of all links. Also, the ports must be at least SFP+ and jumbo frames everywhere. Therefore, Mikrotik CRS326-24S+2Q+RM seemed like a good solution. Within the homelab, it would be reasonable to use one model for Spine and Leaf — this way, I can quickly replace a failed important switch (for example, by temporarily removing one Spine).

- It turns out that one homelab module consists of approximately six mini-PCs with OKD and one Leaf switch. Of these, I plan to use no more than three nodes for Ceph so as not to overload the network with oversubscription. The rest can be cheap compute nodes from used Lenovo ThinkStations.

- With an 80 Gbps channel between Spine and Leaf, one Spine will only run out of space with the fourth Leaf. And two Spines will definitely be enough for everything. If things get really crazy, I can deploy two Edge-Leafs. It’s worth noting that Spine-Leaf is only needed in case of a major expansion of the homelab. My setup will probably be fine with one or two switches for a very long time (two can simply be connected directly).

- All of this should be able to be downsized to approximately: one box for core/firewall virtual machines, one switch for servers (instead of an entire fabric), three OKD nodes, a home access switch, and one Wi-Fi router. If there is plenty of time for reorganization, the OKD cluster can be reduced to a single machine (SNO). The home access switch can also be removed, and computers can be switched to Wi-Fi or connected via twisted pair directly to the access point. Seems pretty good.

Let’s talk a little about security. I will adhere to a defense in depth strategy, i.e., I will not rely on a single security measure: if one measure fails, the second or third will work. And even then, security through obscurity cannot be a key security measure, but it is quite suitable as an additional measure to real security measures. Of course, I’m not well-known enough on the internet to be targeted for attacks, but I’ll play it safe anyway:

- You won’t see my homelab domain anywhere: I’ll replace it everywhere. The same goes for IPs, subnets and some subdomains.

- I will most likely deliberately omit some security configuration details in future articles. But I will try to cover everything that is important and necessary for everyone.

Plus, no one is immune to attempts by Chinese/Indian/Russian/Brazilian botnets to join you to themselves:

- There will be a minimum of publicly available services, and those that are available will work through a VPS with a reverse proxy. The main external access to services will be through Headscale/Tailscale. Geoblocking will also be used.

- Incoming traffic from ISPs will be scanned on an external OPNSense. Traffic from the reverse proxy will be scanned on the proxy itself and on the internal firewall. In addition, there will be an L7 firewall (WAF) in OKD itself. Candidates for these roles include Suricata, CrowdSec, and open-appsec. Probably all of them together.

- The network will be zero trust, as far as is feasible for a homelab. Minimal privileges, 2FA, encryption, authentication, authorization, and logging everywhere.

- Weaponized assault penguins will also be involved in the defense!

Short-term plan

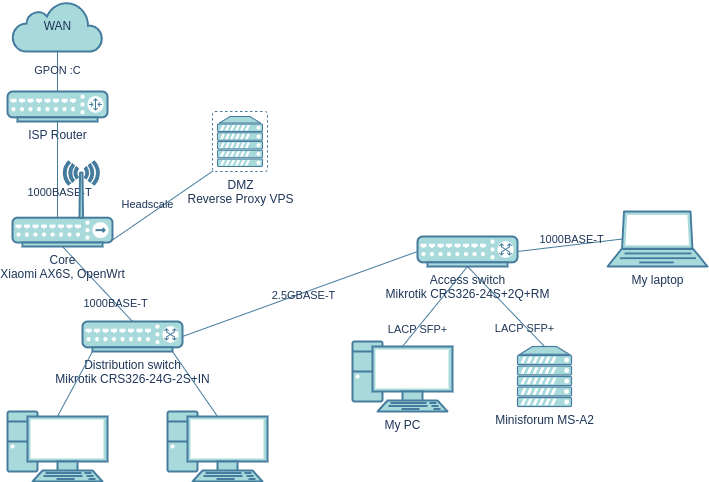

So, we’ve sketched out our dream home data center, but where do we start? I’ll start with what I already have, adding just one machine and a switch:

Here is the current setup:

- Shitty GPON and router from the provider.

- Core directly on OpenWrt, combined with a Wi-Fi access point. I already have it, I’m connected through it right now.

- CRS326-24G-2S+IN is also already there, it will handle the distribution of the network throughout the apartment (with the wiring already in place in the walls). The computers of other family members will be connected to it.

- The wiring in a rented apartment largely determines the connection scheme and channel bandwidth. I hope that real Cat 5e and 2.5GBASE-T will work in the walls. I’ll connect two Mikrotiks to it. The more powerful Mikrotik CRS326-24S+2Q+RM marks the beginning of the homelab. The MS-A2, my computer, and my laptop will be plugged into it. It would be nice if I could get Jumbo Frames working between the computer and the server. My laptop’s docking station doesn’t support them, and there’s no need for them with this channel.

- As you can see, there are far fewer security measures. That’s okay, we’ll gradually build them up.

Since my computer will be located in the same place as the lab, it can be connected to the lab via a high-speed link. This makes it (somewhat) part of the homelab! It will be interesting to see how Nextcloud, for example, will cope with such bandwidth. Probably not very well, but we’ll see.

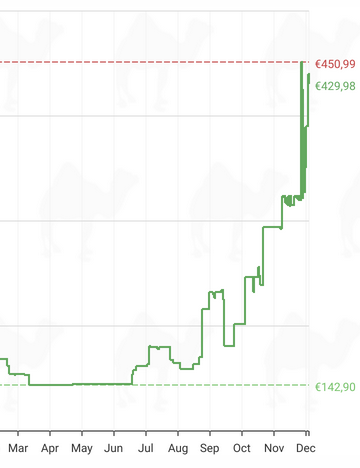

Memory shortage

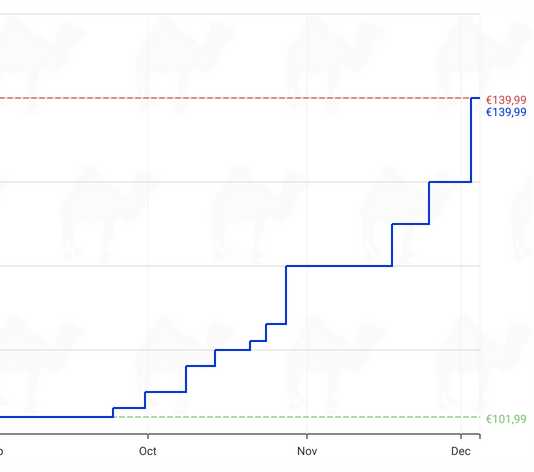

Finally, let’s talk about the problems of building any computer right now. I wrote this text on November 2, but the article was delayed for more than a month, and the situation has worsened. At the moment, there is a sharp jump in the price of RAM and SSDs due to the AI data center boom. At first, I thought I was delusional and crazy, but my doubts disappeared when I came across this post on r/homelab. At the same time, even consumer components are becoming more expensive. Either production lines are giving preference to the production of more profitable server hardware, or server hardware is running out and desktop hardware is being used instead (probably both). These are the times we live in.

For example, here is the more expensive DDR5 SO-DIMM 2x32GB RAM from Crucial, which I installed in my Framework 13.

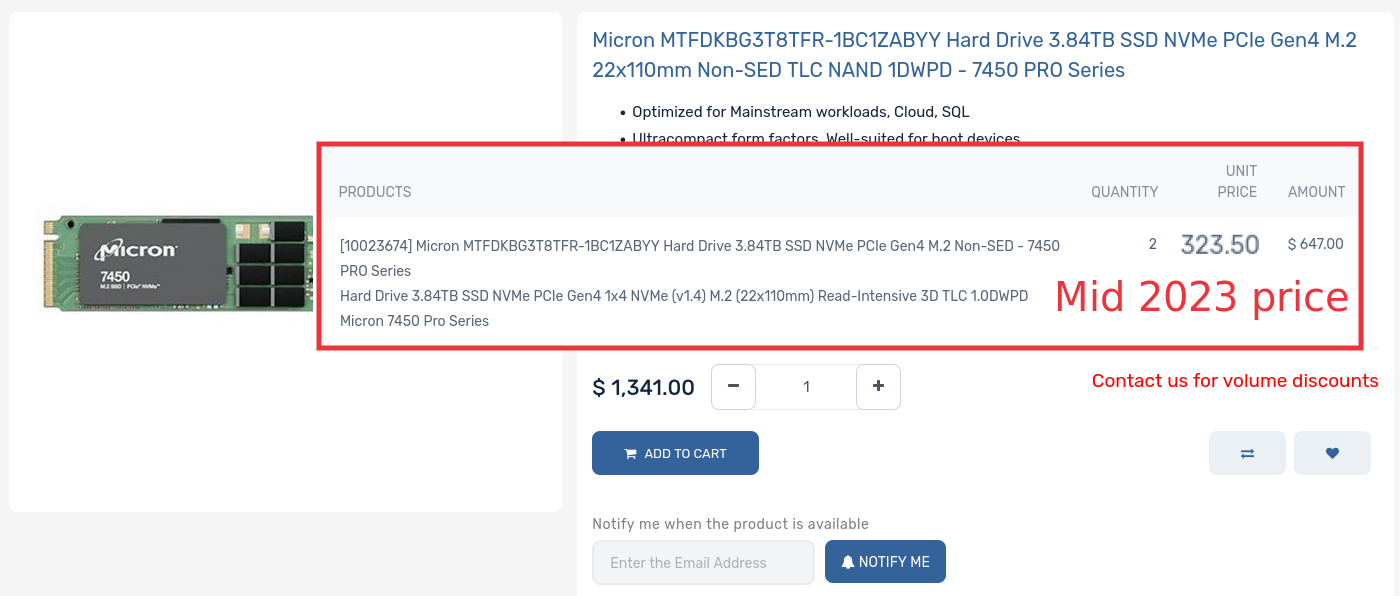

Or take enterprise SSDs, which I bought two years ago at a quarter of the price.

Meanwhile, prices have risen for Silicon Power’s DRAM-less PCIe 4.0 SSDs.

Sigh, it was only recently that GPU prices started to approach MSRP :C. And I have a feeling that these prices will stay with us until 2027 or even 2028, when the AI data center and services bubble bursts (presumably).

Thanks for reading, I hope you found this article interesting! I sold my old computer, so the next article will be about building a Micro-ATX PC for gaming, work, and interacting with my homelab. See you soon!

[1]. By the way, there’s a guy who literally built a homelab in a container. I love his setup!