- 06 Dec, 2025 *

How resilient is your prep when your players zig instead of zag? For the most part these days I mainly aim to run blorb-style prep that is, by nature, pretty ruggedized against player decisions session-to-session. Some advice that I see in more traditional forums is that it is okay to just tell players when they are butting up against what you have prepared for game night as a means of either wrapping up a session early or corralling their decision space. I absolutely agree with this! I have not run for tables where I would not feel confident telling players that I have run out of material.

But how can we assess what may make your prep more or less fragile?

I’m sort of talking around the first case study that I want to make, so I’ll stop being coy. The prototypic…

- 06 Dec, 2025 *

How resilient is your prep when your players zig instead of zag? For the most part these days I mainly aim to run blorb-style prep that is, by nature, pretty ruggedized against player decisions session-to-session. Some advice that I see in more traditional forums is that it is okay to just tell players when they are butting up against what you have prepared for game night as a means of either wrapping up a session early or corralling their decision space. I absolutely agree with this! I have not run for tables where I would not feel confident telling players that I have run out of material.

But how can we assess what may make your prep more or less fragile?

I’m sort of talking around the first case study that I want to make, so I’ll stop being coy. The prototypical example that I have in mind is, what happens when your players decide to avoid a fight? How much game do you have left?

Best Laid Plans

I’ve both played and run a lot of dungeons and dragons fifth edition. If you have a 2-3 hour game session planned, a bespoke or setpiece combat encounter can easily take up half of that session. It’s the subsystem of the game with the greatest rule density and the most formally-encoded/rules-as-written mechanics interactions. If you are preparing your game on a per-session basis, a specific combat encounter can easily be the center of gravity of the material that you prepare for game night. For the sake of word economy, let’s assume that you have already taken steps to make the encounter sufficiently "sticky", i.e. it’s a gate criterion for progress toward the players’ goals.

Before we return to our original problem statement of resiliency, though, let’s think about what encourages players to choose to engage with or sidestep combat, and then we can potentially generalize that out to other obstacles in our games. I’m going to frame a lot of these examples in terms of player consent to [combat] because I think it makes it clearer when they may choose to avoid a fight. I may end up defaulting to some terms that come out of Magnolia Keep’s Combat as my Balls post because it’s a thoughtful piece that helps capture a lot of parallel thoughts.

When do Players Pick Fights?

Players consent to combat encounters when it’s the default scene in front of them. If you run a game where players are on board with the GM’s plans and the GM determines that this is the right time in the narrative for an encounter, lots of players will consent to that. In my experience this is especially true in "feature length" campaigns where combat is considered the best subsystem for presenting an action-packed climax in a 2-5 hour adventure. 1.5) Players consent to combat encounters when it feels narratively appropriate. I was originally going to make this its own bullet point but I realize that it’s really subsidiary to combat-as-default-scene. If a villainous NPC has been raising hell and the GM presents a chance to serve them a comeuppance, players are likely to engage with that encounter. 1.

Players consent to combat encounters when combat is fun. I find this to be especially true with players who feel more comfortable as audience members during other forms of role play; combat is a chance for some players to take advantage of a structured interface that lets them directly contribute to a scene. As a corollary to this, if your game’s advancement system focuses on increased combat aptitude, it is fun to show off your new tools; every combat that you avoid is a missed opportunity to swing your cool sword whose thirst can only be slaked with blood. 1.

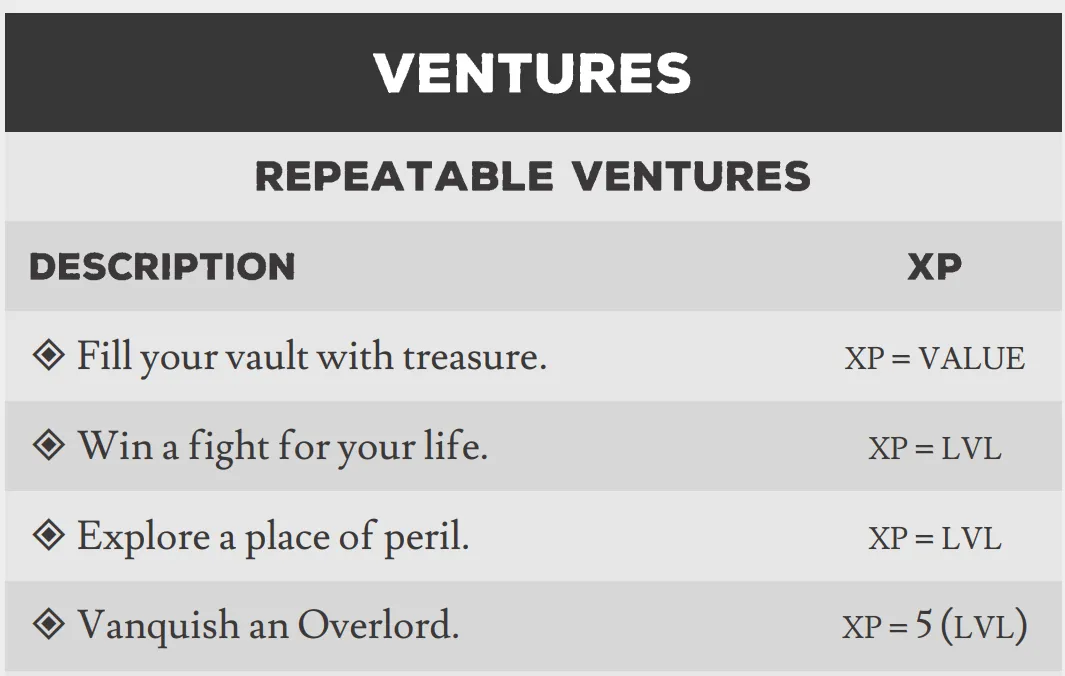

Players consent to combat encounters when it helps them to achieve their goals. The easiest example of this is game systems which grant experience points or some other form of intrinsic reward for vanquishing enemies. Indirectly, combat may remove an obstacle in between the players and their goals that can’t otherwise be avoided or subverted. If the dragon is guarding a hoard of gold that you need to extract, slaying the dragon is going to enter the decision space.

Trespasser 2nd Edition, Page 85. Trespasser wears on its sleeve what it is about!

- Players consent to combat encounters when they have the resources to spare. If players believe that the cost of a fight is something they are willing to pay, then they will probably accept that risk. This is why modern tactics games which center combat typically provide player characters with tools and resources which exist and refresh within the context of the combat scene. 4e’s fabled Encounter Powers fit this template. In Liz’s terms, this is the antithesis of Combat as Entropy.

Takeaways

I posit that when the four conditions here are not met, you are incentivizing players to seek alternatives to combat. I feel like these consent conditions sort of naturally propose their own converses, so I won’t hit it too hard.

When do Players Avoid Fights

Players avoid combat when it does not feel narratively appropriate. This is the "I don’t think my character would do this" condition. 1.

Players avoid combat when combat is not fun. If the combat procedure is boring, slow, complicated, or generally annoying, then players will likely seek an alternative. How many horror stories have you heard about grappling in third edition DND? If the game is mostly about combat and the combat is not fun, they will probably seek out a different game, but I doubt that has ever happened to anyone reading a tabletop blog. 1.

Players avoid combat when it does not serve their goals. His Majesty the Worm is a game with a very fun combat subsystem, but vanquishing foes does not provide character advancement so my players have not entered a challenge phase since July.

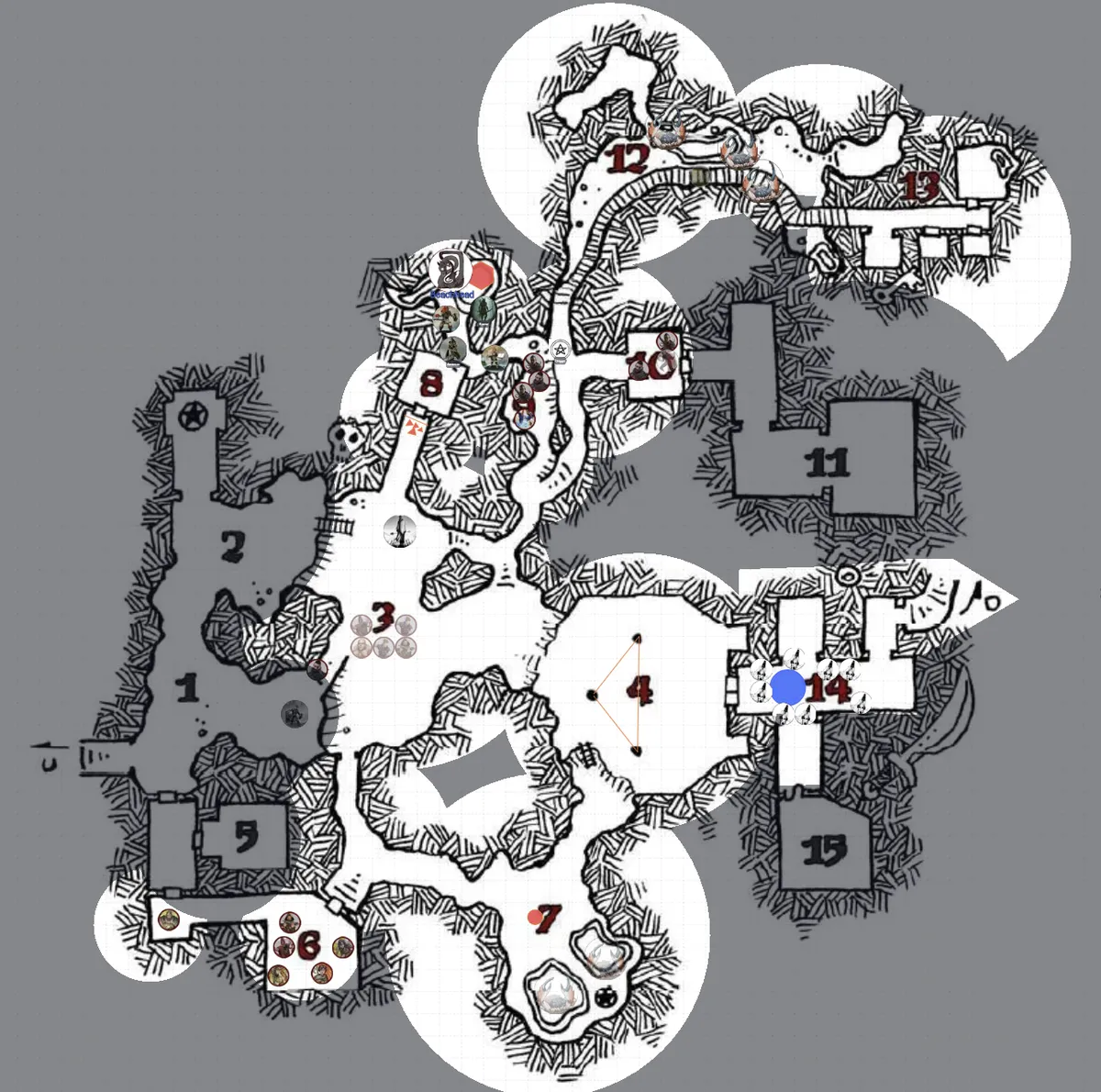

My players found themselves trapped in Atarin’s Delve from Dyson Logos and realized that combat would do them no good; I had planned this level as an exhausting string of combats and my players wheeled and dealed their way through it as smooth-talking operators

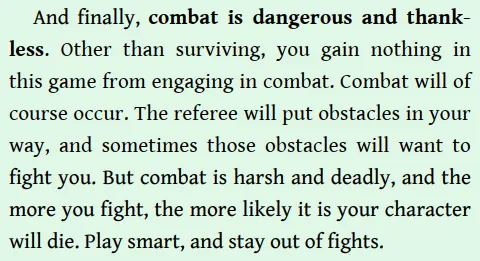

- Players avoid combat when it would impose unacceptable risk or cost. This is the only bullet point I want to be very clear on, because I have interacted with it from several angles as a player and as a GM. The simplest example of this is that when player characters are very fragile, players are unlikely to pick fights that they may lose. This is the condition that games like Outcast Silver Raiders are trying to impress on players when the rules themselves describe combat as a fail state.

Outcast Silver Raiders, Page 11

There is an important corollary to this, however. Traditional games like 5e and second edition Pathfinder have a lot of tools for their vision of encounter balance. These tools tend to condition players to assume that anything that can be engaged in combat will present a challenge that falls within an acceptable band of risk or difficulty. This expectation can be subverted to dramatic effect, but needs to be telegraphed to certain types of players; bold players may need to be directly told that an enemy cannot be defeated with the tools at their disposal and timid players may need to be told when an enemy is appropriately calibrated.

Takeaways

If you are designing your game prep around a combat encounter, you may need to put yourself in your player’s shoes and think about whether the scenario may meet one of the above conditions. If it does, you may need to have contingency plans in place for enterprising players who may avoid a fight. This topic is also where the classic case of the Quantum Ogre, as revisited by Fluorite Guillotine comes into play. If players make a decision with the direct intent of avoiding a combat and you alter the fiction to force the encounter, you are not respecting the agency of the players and you really ought to present reasonable alternatives.

Generalizing the Obstacle

I’ve spent a lot of time here talking about combat in traditional RPGs because, narratively speaking, combat is an obstacle in an adventure. The character’s choice to engage with or avoid combat is an opportunity to express how they approach conflict and stressful situations. This post from All Dead Generations helps to capture how obstacles are key to non-combat play.

Mechanically speaking, combat in these games is a change in subsystems and a change in timescale - hence the inherent drama in saying "roll for initiative". There are lots of games where there is no separate combat subsystem, or entering a violent encounter does not change the structure of the game-as-conversation. The Cypher system, for example, has slightly different procedures at play during a fight than during other exploration, but it still uses the same core resolution mechanics as the rest of play. Most Powered by the Apocalypse games have similar relationships between combat play and other play.

Thus, in one of these games which does not differentiate between a violent solution to a problem or a pacifistic solution, you are already incentivized not to structure your game preparation around combat. Hence, excellent advice like this from the Cypher book:

[...] for now, remember this point: no single encounter is so important that you ever have to worry about the players “ruining” it. You hear those kinds of complaints all the time. “Her telepathic power totally ruined that interaction” or “The players came up with a great ambush and killed the main villain in one round, ruining the final encounter.” No. No, no, no. See the forest for the trees. Don’t think about the game in terms of encounters. Think about it in terms of the adventure or the campaign. If a PC used a potent cypher to easily kill a powerful and important opponent, remember these three things:

- They don’t have that cypher anymore.

- There will be more bad guys

- Combat’s not the point of the game—it’s merely an obstacle. If the players discover a way to overcome an obstacle more quickly than you expected, there’s nothing wrong with that. They’re not cheating, and the game’s not broken. Just keep the story going. What happens next? What are the implications of what just happened?

I think this advice is worth taking to games that do employ a separate subsystem for combat encounters, but it requires some elbow grease to make work, so let’s talk about what that might look like.

Alternatives to Combat

When presented with an opportunity to fight, the sort of classic alternatives are to sneak around the fight or to talk your way out of it. These are both reasonable impulses in lots of adventures! They very much change the tone of the narrative from high-octane action to political drama or to a tense thriller. The challenge here from a GMing perspective is that lots of games have a much higher rule density allocated to their combat subsystem than to, say, sneaking or to negotiation.

In vulgar terms that I don’t necessarily agree with, you could say that there is "less game" there if the players take a pacifistic route; if the GM doesn’t have contingency material prepared, there is strictly speaking less game though! In these games, avoiding a fight is likely to save the players a lot of time and they will burn through more of the GM’s prep!

Before we get to any prescriptive recommendations, though, I think it’s worth understanding what is driving the players’ decision to avoid a fight. If they are avoiding a fight to conserve resources, for example, then you need to assess the rest of your prep and see what the consequences are for your adventure if the players have an unexhausted kit and whether you want to reward that as "smart" play. If they are avoiding a fight because fights aren’t fun, then you need to assess whether other obstacles in your game are fun!

But that’s the point that I want to get to - if you depend on combat as a time/space-filling activity in your game and you find that your players seek alternatives to combat, can you include alternate subsystems that interact with your players’ tools and that provide engaging gameplay? I think Draw Steel provides surprisingly solid support for alternatives to combat! It is a game that is unabashedly about tactical combat, but the Negotiation and Montage Tests are complete subsystems which mechanically interact with class features and player advancements. A Victory from a Negotiation provides the same mechanical benefits as the same victory from going sicko mode on the subject of the negotiation. In Baldur’s Gate 3, you get just as much experience points from de-escalating a tense situation as from slicing someone in half.

This is good tech! It’s worth considering that de-escalation and conflict avoidance can become optimal play if it is always faster and less resource-intensive than fighting - arguably this is a good takeaway for real life, but sometimes in tabletop it’s fun to swing a sword. One way to modify the incentive structure is to make dealing with NPCs Expensive and Irritating as my friend at Forlorn Encystment has documented in his series on the implied setting of ADND. Similarly, sneaking around a setpiece fight doesn’t have to be a single group stealth check, it can take players on a circuitous and hazardous route that requires resource expenditure or at least active player engagement.

Conclusion

So let’s revisit our original question. How resilient is your prep to a change in player plans? When players avoid a big setpiece obstacle, do you have the notes or the improvisational tools to still engage your players’ interests? Does your game allocate sufficient rule density to other subsystems to keep alternative plans fun, challenging, and rewarding?

If your players are consistently failing to engage with your hooks or the game’s challenges on its own terms, do you need to talk to them about playing a different game or creating new characters who won’t ignore the call to action? Are you failing to meet your players’ expectations of their consent conditions for combat?

I think this is only a problem if it’s a problem, but I hope to hear whether this resonates with anyone who has had similar experiences.