When COVID hit, healthcare systems around the world were turned upside down. Hospitals cleared beds, routine appointments were cancelled and people were told to stay at home unless it was urgent. In England, visits to family doctors and hospital admissions for non-COVID reasons fell by a third in the early months of the pandemic. Medical staff were redeployed, routine clinics were cancelled and diagnostic tests were postponed.

Against this backdrop, the number of people newly diagnosed with long-term health conditions fell sharply, as our new study, published in the BMJ, has found. My colleagues and I used anonymised health data for nearly 30 million people in Engla…

When COVID hit, healthcare systems around the world were turned upside down. Hospitals cleared beds, routine appointments were cancelled and people were told to stay at home unless it was urgent. In England, visits to family doctors and hospital admissions for non-COVID reasons fell by a third in the early months of the pandemic. Medical staff were redeployed, routine clinics were cancelled and diagnostic tests were postponed.

Against this backdrop, the number of people newly diagnosed with long-term health conditions fell sharply, as our new study, published in the BMJ, has found. My colleagues and I used anonymised health data for nearly 30 million people in England to evaluate what happened to new diagnoses across a wide range of chronic diseases.

The drop in diagnoses during the early pandemic was most pronounced for conditions that usually rely on routine tests or specialist review for diagnosis. New diagnoses of asthma fell by over 30% in the first year of the pandemic, while diagnoses of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) dropped by more than half. Both conditions depend on breathing tests that were widely disrupted during the pandemic, causing large backlogs in testing.

Similarly affected were skin conditions such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. While some people may have delayed seeking medical attention for these conditions during a time of unprecedented disruption, others will have been affected by delays in referral for specialist review and diagnosis.

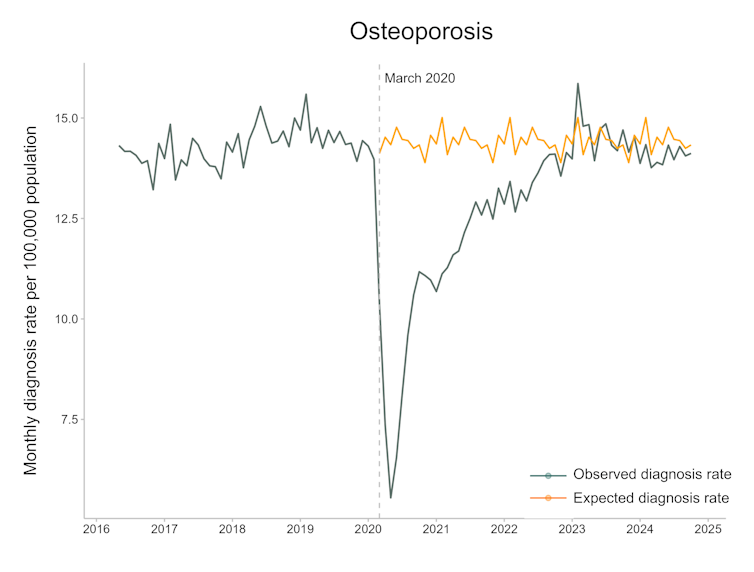

For many conditions, delays in diagnosis matter. Osteoporosis is a common condition in which bone thinning can lead to serious fractures. There are highly effective drugs that can prevent fractures from osteoporosis, but they are usually only prescribed after the condition has been diagnosed.

New diagnoses of osteoporosis fell by a third early in the pandemic and did not return to expected levels for almost three years. As a result, more than 50,000 fewer people than expected were diagnosed with osteoporosis in England between March 2020 and November 2024.

Rate of new diagnoses of osteoporosis in England before, during, and after the pandemic. Projected rates, based on pre-pandemic trends, are shown alongside observed rates.

Patterns of recovery

As the immediate disruption during the early pandemic eased, diagnosis rates for many conditions slowly recovered. The differences in recovery patterns across different diseases have been striking, however. Two conditions stand out: depression and chronic kidney disease.

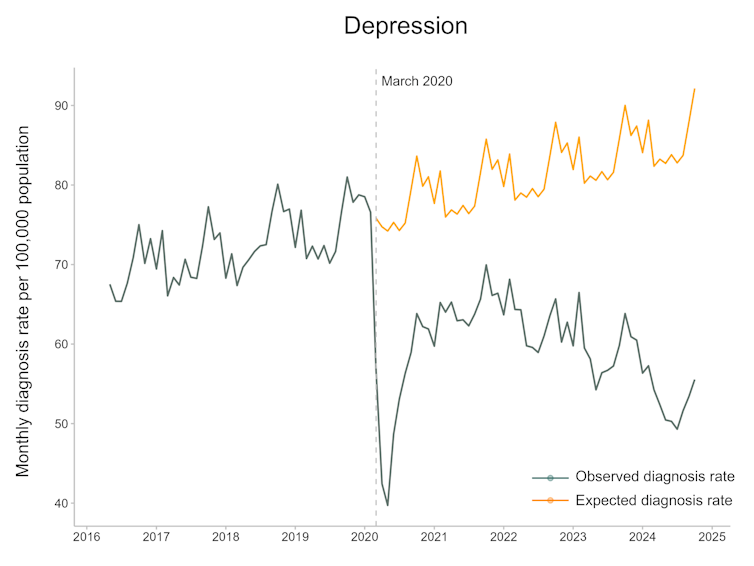

New diagnoses of depression fell by nearly 30% in the first year of the pandemic. Rates then partially recovered, but have dropped again considerably since 2022. This does not necessarily mean that fewer people are experiencing symptoms of depression. A doubling in the number of disability claims for mental health conditions in England between 2020 and 2024 suggests otherwise.

Rates of diagnosis for depression in England have fallen since 2022.

Several factors could help explain this disconnect. Continuing pressure on healthcare services may mean that people are waiting longer for formal diagnoses.

People may also be accessing healthcare services differently. In 2022, guidelines for depression management in England were updated to recommend talking therapies (such as cognitive behavioural therapy) as an initial treatment for mild depression, rather than antidepressants.

In England, people can refer themselves directly for talking therapy without needing to see a doctor first. As a result, some people receiving support for depression symptoms may never receive a formal diagnosis in their medical records, giving the impression that diagnosis rates are falling.

Changes in disease classification may also be playing a role. While depression diagnoses have declined, new diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder have risen sharply in England. This may reflect a shift in how overlapping symptoms are being interpreted and labelled, rather than sudden changes in how common they are.

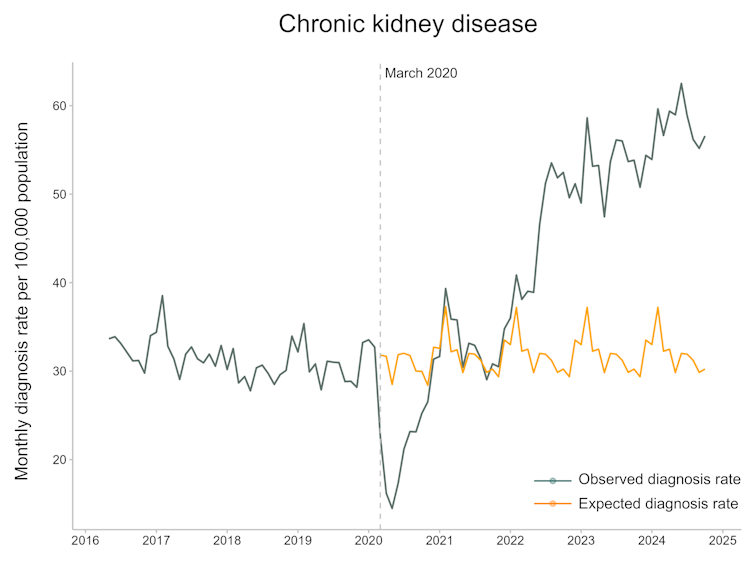

Chronic kidney disease shows a very different pattern. Diagnosis rates have doubled since 2022, making it one of the few conditions in the study to have increased above pre-pandemic levels. There are several different ways of interpreting this finding.

Rates of diagnosis for chronic kidney disease in England have doubled since 2022.

The recent increase in diagnoses might result from improved detection of undiagnosed kidney disease. Recommendations in England were updated in 2021, recommending routine testing for kidney disease in people at higher risk, such as those with diabetes or high blood pressure.

Importantly, new treatments for chronic kidney disease mean that earlier detection can improve outcomes for patients.

Another possibility is that the pandemic itself has contributed to an increase in chronic kidney disease, directly or indirectly. COVID infection has been linked to lasting reductions in kidney function in some people. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of other conditions, including diabetes, may also have had knock-on effects on kidney-related complications from these diseases.

One of the most important messages from the study is that it is now possible to detect changes in disease patterns far earlier and more comprehensively than was previously imaginable. Until recently, data often became available years after events had already unfolded. By the time patterns were recognised, opportunities to respond had often passed.

Secure, anonymised analysis of medical records allows researchers to track diagnoses and treatments in near real time, revealing the effects of disruptions, recoveries, and new guidelines as they happen. While the findings highlight ongoing challenges for healthcare, they also show that timely data can help guide more effective responses.

And so, while many of the findings from this study are sobering at a time when healthcare systems remain under enormous strain, they also point to a new opportunity. The pandemic may have disrupted care, but it has also driven innovations that have revealed patterns that would once have taken years to detect.