For more than two decades, the Shinawatra family has defined Thai electoral politics. Will their Pheu Thai Party continue to hold sway as voters cast their ballots on Sunday (Feb 8)?

Thailand’s former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his daughter and former PM Paetongtarn (right) arrive at the Supreme Court in Bangkok on Sep 9, 2025. (Photo: AP/Sakchai Lalit)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

03 Feb 2026 06:00AM

BANGKOK: It is a Sunday morning and Nid Wandee and his wife, Patchareewan, have nearly sold out of grilled chicken at a local market in the Lad Phrao area of Bangkok.

It has been a good day for the couple but a rough patch for the family.

Nid, who has been in business fo…

For more than two decades, the Shinawatra family has defined Thai electoral politics. Will their Pheu Thai Party continue to hold sway as voters cast their ballots on Sunday (Feb 8)?

Thailand’s former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his daughter and former PM Paetongtarn (right) arrive at the Supreme Court in Bangkok on Sep 9, 2025. (Photo: AP/Sakchai Lalit)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

03 Feb 2026 06:00AM

BANGKOK: It is a Sunday morning and Nid Wandee and his wife, Patchareewan, have nearly sold out of grilled chicken at a local market in the Lad Phrao area of Bangkok.

It has been a good day for the couple but a rough patch for the family.

Nid, who has been in business for more than a decade, says customers who once spent freely now buy less, while his family’s costs have kept on rising.

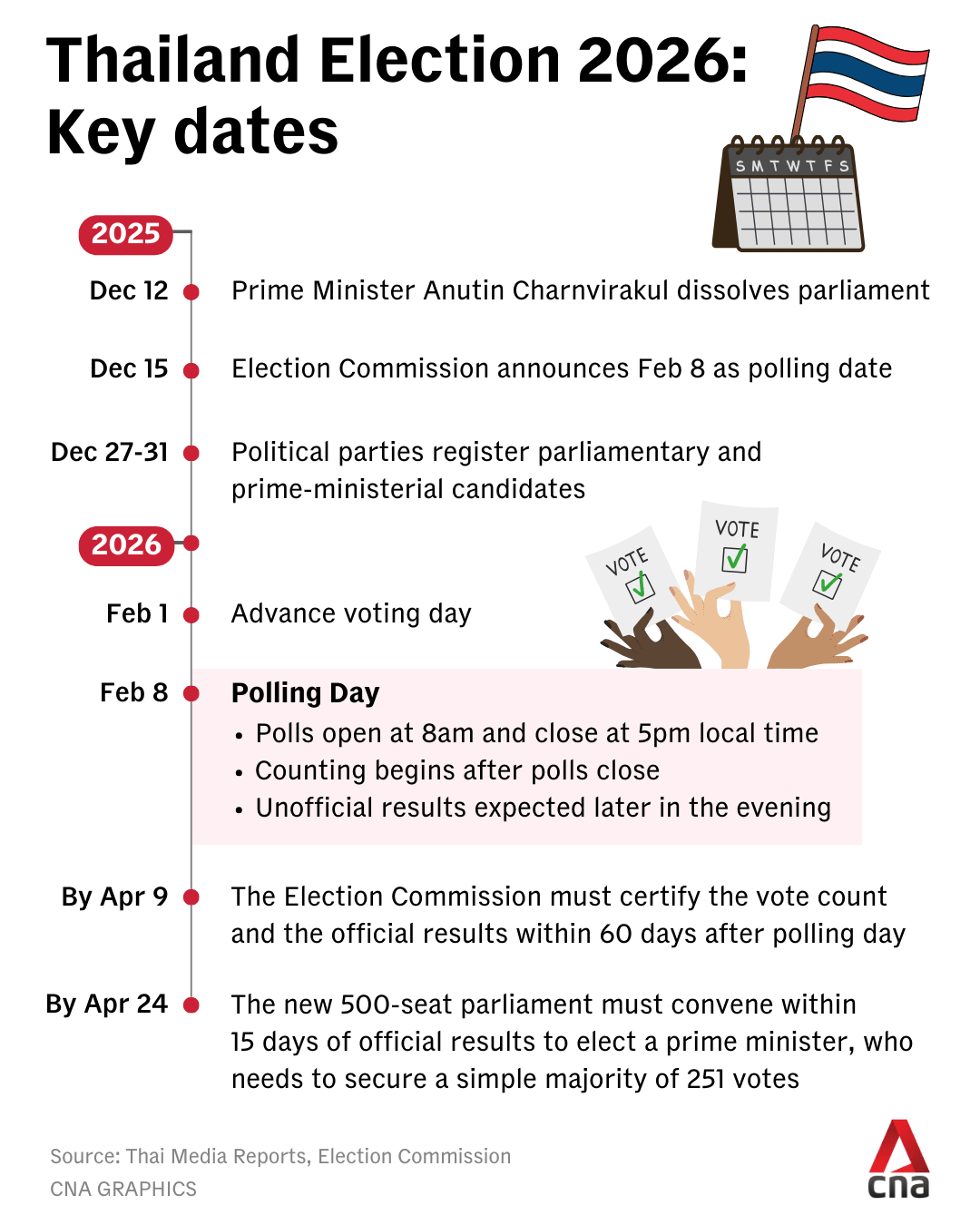

With the Thai economy in the doldrums, Nid, originally from Thailand’s northeast but living in Bangkok, is looking to the general election on Sunday (Feb 8) for answers. And mostly thinking back to better days.

When Thaksin Shinawatra was prime minister in the early 2000s, the populist leader won great support from rural voters and the working class, the likes of Nid.

The upcoming vote will be a test of whether the Shinawatra dynasty still has pulling power in contemporary Thailand, political experts told CNA.

Thaksin’s rise energised a generation of voters who felt, for the first time, that politics worked for them, said Napon Jatusripitak, coordinator of the Thailand Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

“This was literally the first big change in the Thai political landscape, and it dramatically improved the living circumstances of a very broad segment of the Thai population, particularly those in the working class and rural communities,” he said.

“For the first time, Thai people felt that their votes mattered.”

Nid, 48, recalls policies like cheap 30 baht (US$1) healthcare and support for local entrepreneurs and products that made the lives of poor Thais better two decades ago.

The universal health insurance scheme was introduced in 2002 during Thaksin’s time as prime minister from 2001 to 2006. It covered more than 99.5 per cent of the Thai population, who paid 30 baht per healthcare visit at its launch, and particularly benefitted the lower-income.

Like many in his generation, Nid measures today’s politics against what he remembers before.

Nid Wandee and his wife, Patchareewan, prepare grilled chicken at a market in Bangkok. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

Nid Wandee and his wife, Patchareewan, prepare grilled chicken at a market in Bangkok. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

“Maybe my confidence has dropped a little from 100 per cent, but I still believe in Thaksin because those past policies are still in my memory. They make me feel that he was still better than other parties today,” he said.

“That trust comes from remembering how good the economy used to be. We want to choose (a party) like that again. Other parties that came into power later just couldn’t compare to the party we supported before.”

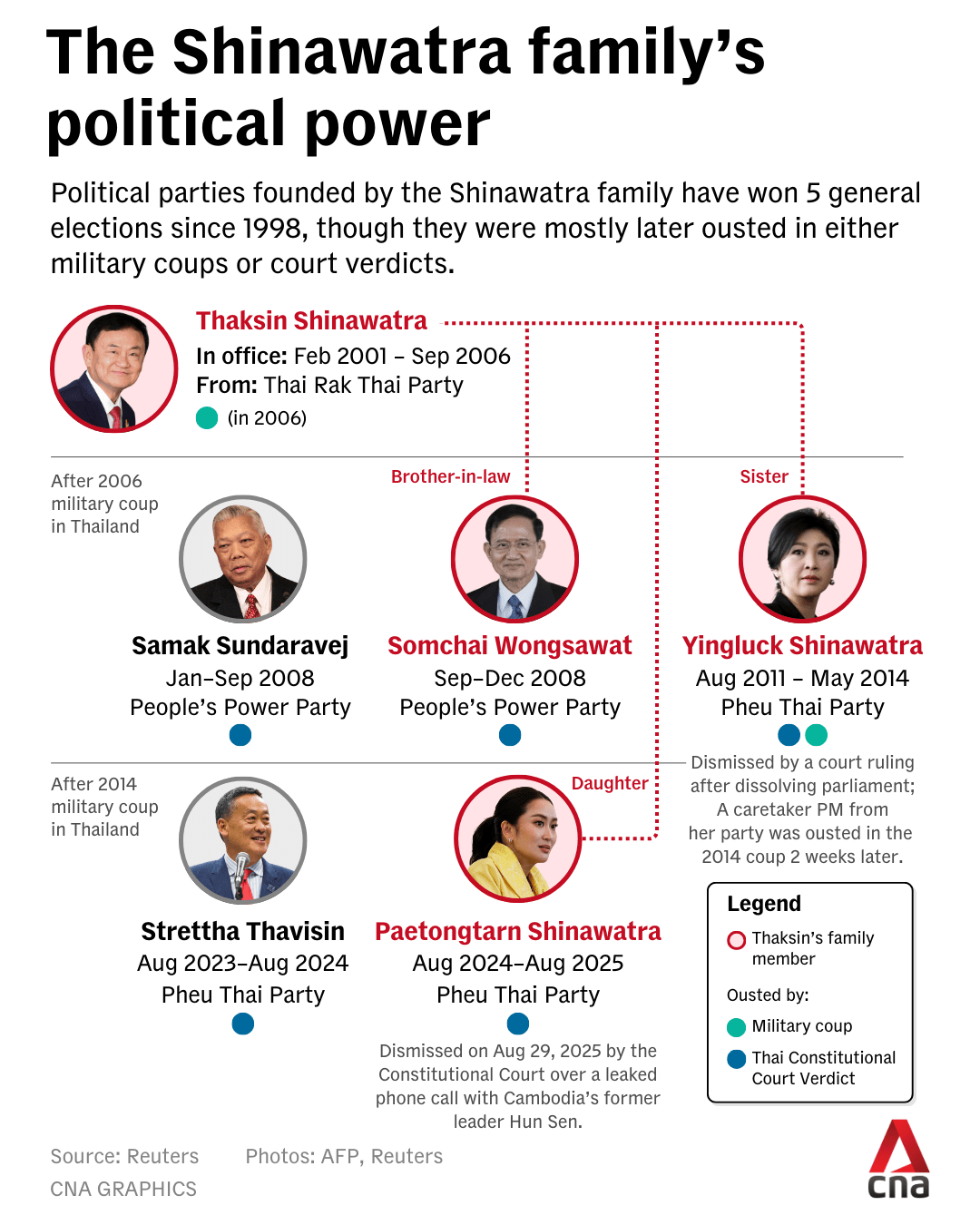

For more than two decades, the Shinawatras have defined Thai electoral politics, mobilising rural voters, reshaping welfare expectations and provoking fierce resistance from conservative elites.

But years in exile, court cases, party dissolutions and generational change have eroded their once-unassailable dominance, experts said.

“Pheu Thai now doesn’t have a clear identity of where they want to position themselves, and that’s not good for marketing. Political marketing used to be the strength of Thaksin and right now, they could not find that identity,” said Suranand Vejjajiva, a political analyst and former minister in Thaksin’s government.

With Thaksin currently in prison for past convictions, his sister Yingluck still in exile overseas after her government was toppled in a military coup in 2014, and daughter Paetongtarn removed as prime minister last year over ethical violations linked to the Cambodia border conflict, the family’s influence is again showing signs of waning.

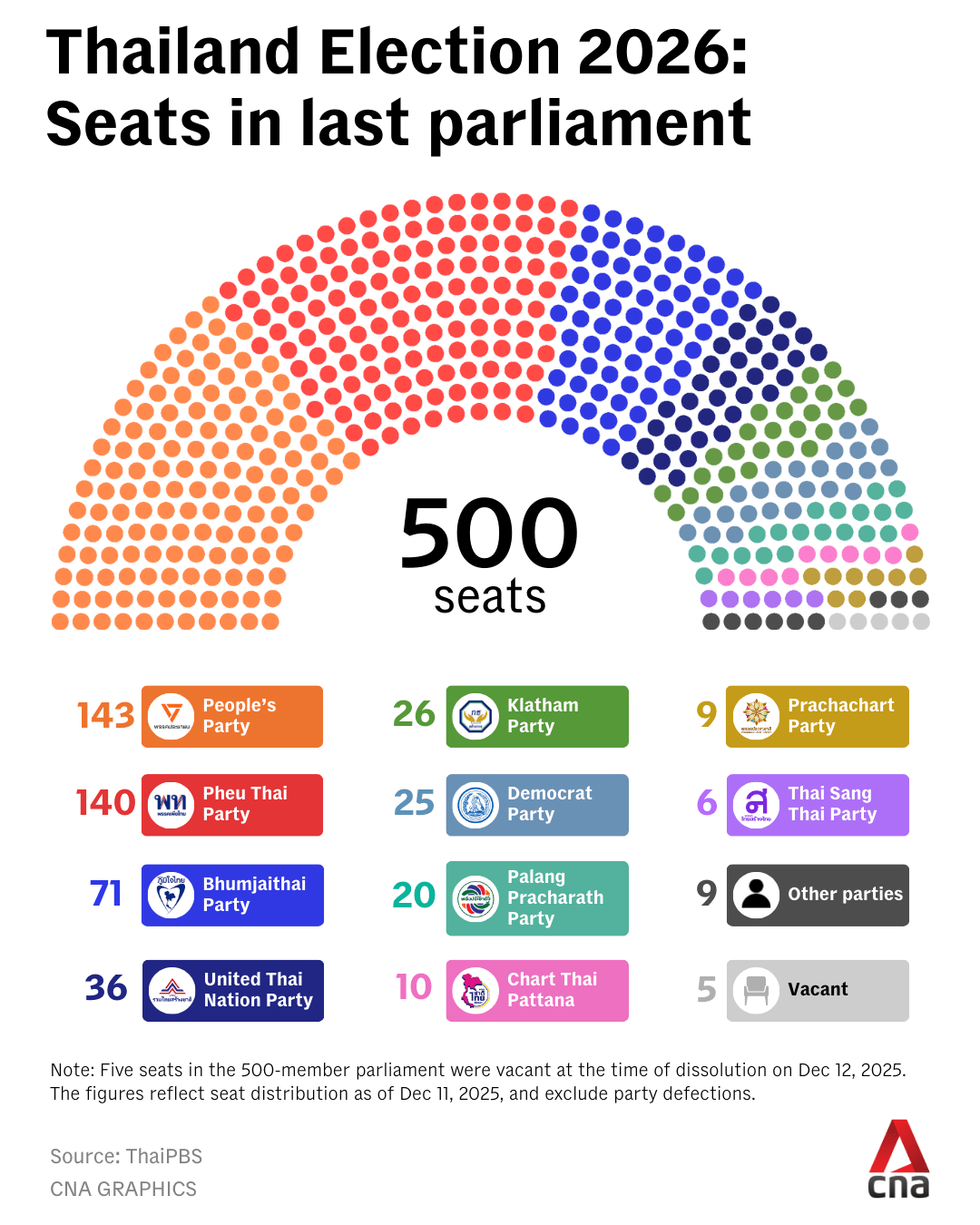

Pheu Thai Party, the family’s political vehicle, is running a distant third in opinion polls ahead of the vote, a position unthinkable at the height of the Thaksin era.

The party was formed in 2008 as a successor to the People’s Power Party, which itself had emerged after the court-ordered dissolution of Thaksin’s original Thai Rak Thai party. Each reincarnation has returned to win elections or command large blocs of parliamentary support, underscoring the lasting power of the Shinawatra-led network.

For younger voters though, the name may no longer have the emotional pull it once held for their parents, said Stithorn Thananithichot, a senior research associate at Chulalongkorn University.

“I think we have about two million people as first-time voters. They look at the party position right now, rather than the history,” he said.

The Wandee family is a case in point: Nid’s daughter, Wanida, is adamant about making her political choices, not inheriting those of her parents.

“I think politics also needs to move forward with the times,” said the 24-year-old graphic artist. “That’s why I feel hopeful that something new could happen.”

Pheu Thai Party’s three prime ministerial candidates, Yodchanan Wongsawat (centre), Suriya Juangroongruangkit (left) and Julapun Amornvivat (right) campaigning ahead of general election, at Siam Paragon in Bangkok on Jan 23, 2026. (Photo: AFP/Chanakarn Laosarakham)

Pheu Thai Party’s three prime ministerial candidates, Yodchanan Wongsawat (centre), Suriya Juangroongruangkit (left) and Julapun Amornvivat (right) campaigning ahead of general election, at Siam Paragon in Bangkok on Jan 23, 2026. (Photo: AFP/Chanakarn Laosarakham)

CAN YODCHANAN DELIVER?

Pheu Thai’s top prime ministerial candidate this time is Yodchanan Wongsawat, Thaksin’s nephew and the son of former PM Somchai Wongsawat.

Yodchanan is a relatively fresh political face, having only run as a candidate back in the 2014 election, a poll that was cancelled amid a military takeover.

Although Yodchanan, 46, is a career academic and scientist, the Wongsawat family has been key to the Shinawatra political network for more than two decades, with various members holding senior party roles at different times.

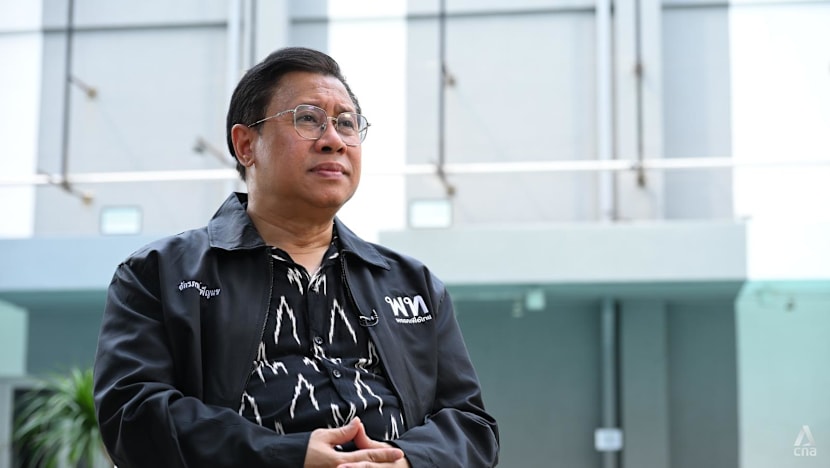

For longtime party stalwart and former Thaksin government spokesperson Jakrapob Penkair, the appeal of Yodchanan is his distinctiveness and distance from past political battles.

“You have to admit that he’s a Shinawatra family member, but he’s quite different from anyone else, educationally, and even personally. So I believe that he’s chosen not because of his being a Shinawatra only, but because he is himself,” he said.

Jakrapob Penkair, former Shinawatra government spokesperson, speaks to CNA in Bangkok. (Photo: CNA/Jarupat Karunyaprasit)

Jakrapob Penkair, former Shinawatra government spokesperson, speaks to CNA in Bangkok. (Photo: CNA/Jarupat Karunyaprasit)

Given the shakiness of Pheu Thai’s supporter base, Yodchanan will need to prove he can bring a fresh approach to the party, said Stithorn.

“I think many, many eyes are looking at him. Can he do something different from the other Shinawatras before or not?,” he said.

Pheu Thai also needs to overcome perceptions that it is simply part of a dynastic system for family members, some of whom may not be the best-suited for national leadership, said Somchai Srisutthiyakorn, Thailand’s former election commissioner.

“With this dynastic mode, the question becomes whether these people truly have ability or are just images created to gain acceptance,” he said.

“We see a mixture: Some are genuinely talented, others are not.”

A LEGACY DILUTED?

The analysts said they expect the party to focus mostly on consolidating or even strengthening its stronghold in the north of Thailand, where Thaksin still commands some love and respect, given his deep and long-lasting ties to the region.

He was born and raised in Chiang Mai province and his family has long been established in the north.

In 2023, however, the party struggled in its traditional heartland.

While it held onto many seats in Thailand’s north, it saw its grip loosen as newer parties like Move Forward Party won key northern constituencies. In the northern city of Chiang Mai, Pheu Thai won only two of the 10 seats up for grabs.

Napon said there have been clear signs on this year’s campaign trail that Pheu Thai is shifting its resources and attention to the north.

Despite losing ground in key areas last election, the party still managed to win 141 seats, the second-highest behind Move Forward Party, which is now the People’s Party.

Pheu Thai formed a government with previously sworn political enemies, including pro-military factions. That arrangement helped facilitate the return of Thaksin to Thailand in August 2023, after 15 years of self-imposed exile to avoid serving jail sentences from 2008 after being convicted in corruption-related cases.

It was a rare bright spot for an administration later plagued by controversies and legal challenges that saw two of its prime ministers - Srettha Thavisin and his successor Paetongtarn Shinawatra - disqualified by the Constitutional Court.

“You have to admit that Pheu Thai failed in the last government,” Jakrapob said.

By August last year, with the Cabinet dissolved, Pheu Thai lacked enough unified support in parliament to elect a new prime minister and form a stable coalition, and its broader political standing had also weakened. It eventually led to Bhumjaithai Party leader Anutin Charnvirakul cobbling together a new coalition and taking power the following month.

Part of Pheu Thai’s problem has been appearing to lose its ideological compass through its tactical manoeuvrings, Napon said. In the process, its identity as an anti-military, populist force to challenge the country’s establishment has become increasingly blurred.

“I think this legacy was diluted the moment that Thaksin made deals with figures in the conservative passageway in Thailand to come home, and his party also formed an alliance with pro-military forces,” he said.

“I don’t think people would take it seriously that the party is a populist vehicle that would usher transformation away from a conservative status quo.”

But a lingering nostalgia for better economic days will favour the party, he added.

This campaign, a focus on debt and cost-of-living relief, especially for low-income households, profit guarantees for farmers and broader plans for economic modernisation indicate a consolidation of policies that voters have welcomed in the past.

Its proposals include a “Nine New Millionaires a Day” proposal that would award daily prizes of one million baht (US$31,800), aimed at drawing more poorer Thais into the formal tax system. But critics argue it would do little to address deeper structural economic problems.

Analysts said this election is notable for its lack of ideological differences on issues, with little to differentiate the major parties and no clear sign of what alliances may form the future government, post-vote.

Jakrapob, a former minister who is running on Pheu Thai’s party list in the election, said Pheu Thai’s campaign is focused on a “pursuit of peace and social order”.

“They are trying to convey that if you choose Pheu Thai, you get a party who doesn’t want to pick a fight,” he said.

“There’s no ideological alignment or misalignment. For Pheu Thai, to open up to all kinds of coalition partners is the right solution for this time of non-ideological Thailand.”

WHAT NEXT FOR THAKSIN AND PHEU THAI?

Thaksin is currently serving a one-year prison sentence on a previously outstanding sentence.

In September, judges decided his six-month stay in a hospital suite in 2023 to 2024 did not legally count as time served. He may be eligible for parole sometime in mid-2026.

The ruling effectively sidelines Thaksin during a critical election cycle, limiting his ability to act openly as a political strategist or power broker.

How he emerges and into what style or role may be dictated by how Pheu Thai performs while he is behind bars, the experts said. He has shape-shifted multiple times; from prime minister to pariah to symbolic figurehead and backroom dealmaker.

While change is afoot around the country, Jakrapob noted, Thaksin remains “a vital issue to the whole political scene”.

“He’s changed from ‘the thing’ into ‘a thing’. So, Thaksin is, I think, increasingly perceived as a legend, as a guiding light, as a guru instead of a player,” he said, adding that he believes Thaksin remains “very much a threat” to the Thai establishment.

Pheu Thai Party supporters at a rally in Samut Prakan on Jan 16, 2026 ahead of the general election. (Photo: AFP/Lillian Suwanrumpha)

Pheu Thai Party supporters at a rally in Samut Prakan on Jan 16, 2026 ahead of the general election. (Photo: AFP/Lillian Suwanrumpha)

Jakrapob sees a future where Pheu Thai, for convenience, would look to empower elements of the party outside of the dominant, dynastic families going forward.

But Suranand said that at a time where political members are quick to shift allegiances to other parties, the Shinawatra factor is key to keeping the party together and effective.

“If the Shinawatra family stopped at some point, if they were thinking to wash their hands (of politics), they would have a very small party left, or maybe none at all. Because people who are still loyal to Thaksin will feel that okay, if there’s no machine or family, I’m not obligated to stay here,” he said.

Having the party as a political vehicle, and ideally part of the government, would also continue to give the Shinawatras important leverage for likely legal challenges ahead, he said.

The party apparatus will be ramping up ahead of the weekend. A poor showing, especially in the majority of cities in the north, could spell the end of Pheu Thai as a serious political player, according to Napon.

“Pheu Thai is on its way to becoming a regional party,” he said. “So if it can’t even do that, then there’s really no future.”

Additional reporting by Jarupat Karunyaprasit and Saksith Saiyasombut

Source: CNA/jb