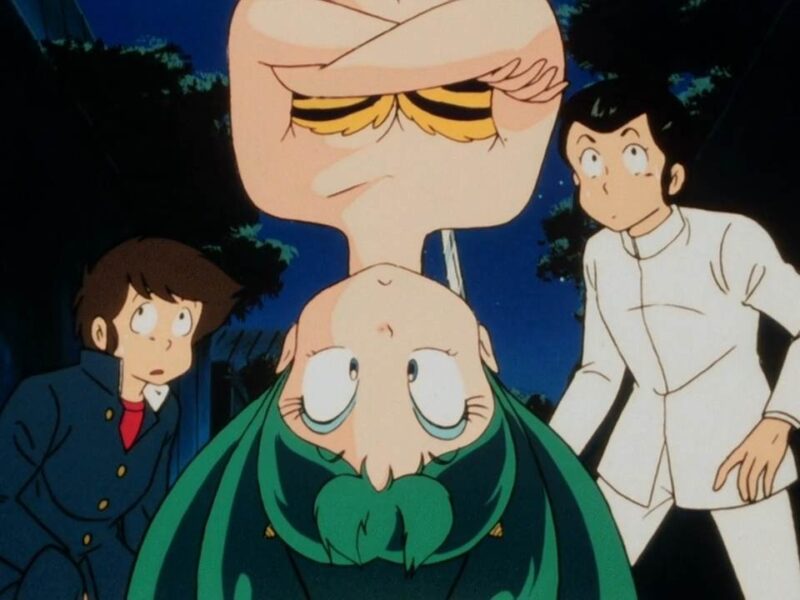

Urusei Yatsura stands as Rumiko Takahashi’s first serialized work. Rumiko, if you aren’t familiar with her, is one of the most influential manga artists: her career spans from 1978 to today. She created a range of works, including Inuyasha. Urusei Yatsura ran as an anime series in the 1980s and was remade in 2022. Urusei features zany, slap-stick comedy, sexy alien girls, and, most interestingly, lots of social commentary under the craziness. I won’t get into the plot of the story here, and I’ve already touched on how the main character Lum can be considered the first tsundere and first waifu. I’ll assume you’ve seen the series in my...

Urusei Yatsura stands as Rumiko Takahashi’s first serialized work. Rumiko, if you aren’t familiar with her, is one of the most influential manga artists: her career spans from 1978 to today. She created a range of works, including Inuyasha. Urusei Yatsura ran as an anime series in the 1980s and was remade in 2022. Urusei features zany, slap-stick comedy, sexy alien girls, and, most interestingly, lots of social commentary under the craziness. I won’t get into the plot of the story here, and I’ve already touched on how the main character Lum can be considered the first tsundere and first waifu. I’ll assume you’ve seen the series in my discussion.

Rumiko’s social commentary varies by episode, but you will see a variety of repeating themes: how female friendships can be threatened by small feuds, how checked out parents can be, the strangeness of modern life, how schools can be authoritarian, and many other elbow nudges. Comedy wraps all of this so closely that, unless you pay attention, you can miss the commentary. Not every episode pokes fun at society. Some episodes are just fun. Which opens the question: how can you know what’s commentary and what’s just a joke? You can read too much into a scene and not enough into another scene. Most writers will include a wink-and-a-nod, an oblique reference to the real-world situation the story comments upon.

Urusei Yatsura does this a few scenes between Lum and Moroboshi. While written back in the late 70s, Moroboshi acts as an embodiment of today’s swipe-dating culture. Moroboshi thinks himself a ladies man, flitting to any attractive woman in his line-of-sight. His advances are rejected every time. This ongoing joke involves Lum shocking him with her electric powers to get him to stop. For her part, Lum cares for Moroboshi despite how he ignores and disparages her. Rumiko likely used this comedic tension to comment on the state of Japanese women back in the 1970s-1980s. During those decades and a good bit of human history, women were still largely dependent on men, and many would have forced themselves to like, or at least tolerate, their unsavory men to protect their physical welfare and the welfare of their children. This forced dependency was changing during this time. Lum, however, is able to zap Moroboshi and punish him in ways these wives could only dream of doing to their husbands. But Lum and Moroboshi’s dynamic and the commentary goes deeper than this, as revealed by a few heartfelt scenes scattered amid the slapstick. A few times Moroboshi believes Lum has had enough of his antics and leaves him. Her absence drives him to realize how much he cares for her and misses her. Yet, when she returns, he falls back to his old womanizing habits. His desire for unconditional love drives him to womanize. His fear of this unconditional love, as Lum offers him, drives him to reject the very thing he wants and Lum offers. Rumiko doesn’t offer an overt reason for why he doesn’t “settle” for Lum, suggesting Moroboshi doesn’t understand the reason himself. Of course, if he did settle down, he would ruin the main long-running joke. But Moroboshi’s lack of self understanding reflects why we also fail to understand why we desire what we do and why we struggle to accept the object of that desire when we receive it. Sure, we can understand the surface desire. Moroboshi desires women, but until he enters a dark period he doesn’t admit what he desires deep down: unconditional, accepting love. So too with us. Most of us desire love and acceptance but chase the surface level. Even loving a waifu is a misfire of this desire to offer love to someone.

Accepting our deepest desire will change us. Once we delve into our spirit and come to understand ourselves, we cannot remain the same person we were. Staring deep into the mirror reveals the ugly, which changes us when we accept and seek to correct this ugliness. The mirror also reveals the good, which changes us when we realize we can attain higher virtue. When we delve into our spirit, we cannot fall into the same self-delusions. We may fall back into the same habits, but we won’t be able to entirely forget the self we saw. Moroboshi experiences this problem. He returns to his antics each he reunites with Lum, but his returns to habit differ as evidenced by his behavior the next time they separate. After one separation scene, for instance, he wraps his arms around Lum’s shoulders–something he had never done before. Rumiko uses Moroboshi’s glacial development to point toward how glacial our own changes are. Change can take years, decades, or a lifetime to take hold. But you have to choose to accept yourself and what you already have before change begins. Moroboshi already has everything he desires in Lum if he would only accept her. But he fears the change to himself that acceptance would force. He would no longer womanize, and his identity revolves around this habit.

This theme appears over the course of many episodes. Rumiko turns the wheel of this commentary slowly, only a few degrees every few episodes. However, the increasing despondency Moroboshi feels marks how this wheel turns. Rumiko’s commentary about the human condition crouches in the slapstick, making you wonder if you even saw it. The craziness of the situations also suggests the craziness of modern life and the craziness of how we function as humans. We are quite ridiculous and laughworthy in our contradictory behavior. We cannot accept what we want, and when we do accept it, we quickly take that previous desire for granted. Moroboshi takes Lum for granted just as husbands (not all, of course) took their wives for granted and vice versa. Moroboshi keeps swiping through the women around him when he’s already has a “right swipe” in Lum. Moroboshi is a good example of a loser man: unable to settle down, accept what he already has, and otherwise step up as a responsible man. He makes for a good laugh, but your laughter might be a bit uncomfortable if you are similar to him.

Rumiko’s work explores the human problem and how we fall into illusions that snowball to crazy levels, which manifests in the insane comedy of Urusei Yatsura and Ranma 1/2. All of the characters in Urusei Yatsura desire something that they cannot accept, whether it’s a friendship, a love, a rivalry. The characters cannot accept their desire when its handed to them, which drives the comedy.

Urusei Yatsura isn’t a deep dive into human problems or the theme I present. It only points toward these issues and then smiles and winks. Rumiko’s work isn’t Ghost in the Shell, but the jokes are designed to make you think a little, opening the door enough to allow you to look inside the social problem. Rumiko’s comedy nods and moves on only to circle back around from a different direction to nod and wink again. Urusei Yatsura’s comedy won’t sit well with everyone. Japanese comedy can be an acquired taste. Rumiko does a good job at showing us just how ridiculous life can be by taking that ridiculousness and multiplying it by 100. Next time you watch a comedy like Urusei Yatsura, try to watch for subtle social commentary and themes about life. You won’t always find it, but when you do, the joke becomes more interesting.