- 04 Jan, 2026 *

Understanding how multithreading and multiprocessing work enables you to make the most of your hardware resources. I’m specifically going to focus on Python web frameworks and how to set up your web server to handle as many concurrent requests as possible. I’ll explain what happens under the hood with both code and figures 🚀

All code and figures used in this post are available here.

Single-threaded Django app

Let’s start with a simple Django web API. It has a single endpoint /currency/convert that returns the exchange rate from one currency to another. The Django backend receives the request, converts the input currencies to lowercase, and sends a query to the database to get the exchange …

- 04 Jan, 2026 *

Understanding how multithreading and multiprocessing work enables you to make the most of your hardware resources. I’m specifically going to focus on Python web frameworks and how to set up your web server to handle as many concurrent requests as possible. I’ll explain what happens under the hood with both code and figures 🚀

All code and figures used in this post are available here.

Single-threaded Django app

Let’s start with a simple Django web API. It has a single endpoint /currency/convert that returns the exchange rate from one currency to another. The Django backend receives the request, converts the input currencies to lowercase, and sends a query to the database to get the exchange rate.

For simplicity, we execute time.sleep(5) to simulate a DB call that takes 5 seconds:

def convert(request):

from_currency = request.GET.get('from').lower()

to_currency = request.GET.get('to').lower()

return HttpResponse(convert_currency_io_bound(from_currency, to_currency))

def convert_currency_io_bound(from_currency, to_currency):

time.sleep(5) # DB uses 5 sec to respond

if (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "gbp"):

return 0.75

elif (from_currency == "gbp" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.33

elif (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "eur"):

return 0.86

elif (from_currency == "eur" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.16

If we run this project with python3 manage.py runserver --nothreading and send two API calls at the same time, we see that it takes ~10s to get a response to both requests:

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200 | 5.0367s

[2/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200 | 10.0455s

Total time: 10.0472s

This is because the web app is processing the request sequentially. To understand why, we need to take a peek under the hood.

When we ran python3 manage.py runserver --nothreading, an OS process was created that runs your Django app and processes incoming HTTP requests. Since we added the --nothreading option, the process runs with just a single thread.

If you are unsure about the differences between processes and threads, GeeksforGeeks has a nice explanation. Essentially, threads are "lightweight processes" created by actual processes. While processes have their own isolated memory space, threads share the memory of their process among them.

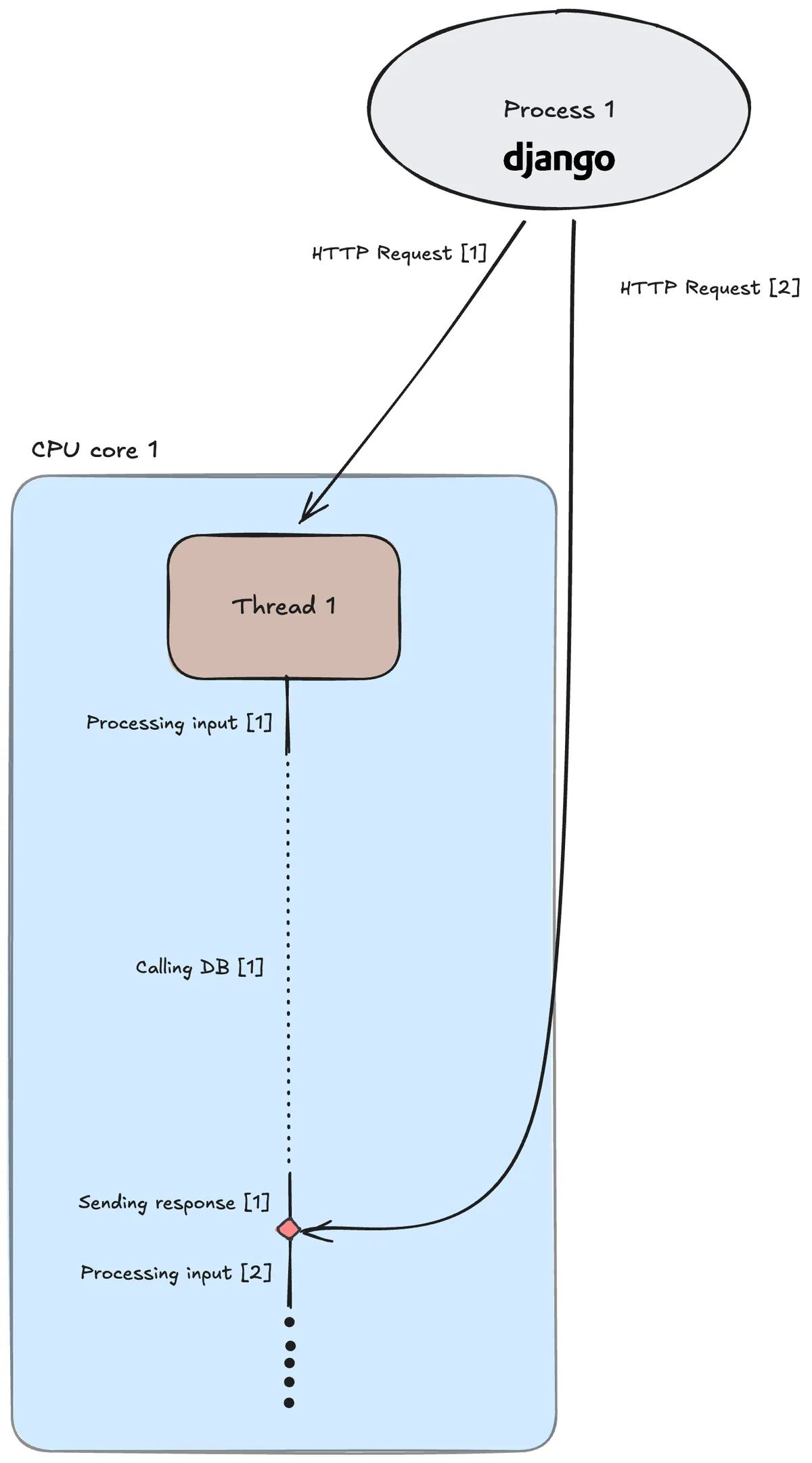

Below is a diagram of how the process delegates the requests to the thread:

Figure 1: A single-threaded Django app processing requests sequentially.

Notice how the DB call, an I/O operation, takes most of the time. This is because, as it is written now, it’s a blocking call, meaning that the Python program won’t execute any other code before it is finished. This is not optimal, as we could’ve started on the second request while waiting on the DB call for the first.

Multi-threaded Django app

Luckily, Django handles this out of the box. If we omit the --nothreading option and simply run python3 manage.py runserver, our requests will be processed concurrently:

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200 | 5.0355s

[2/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200 | 5.0360s

Total time: 5.0370s

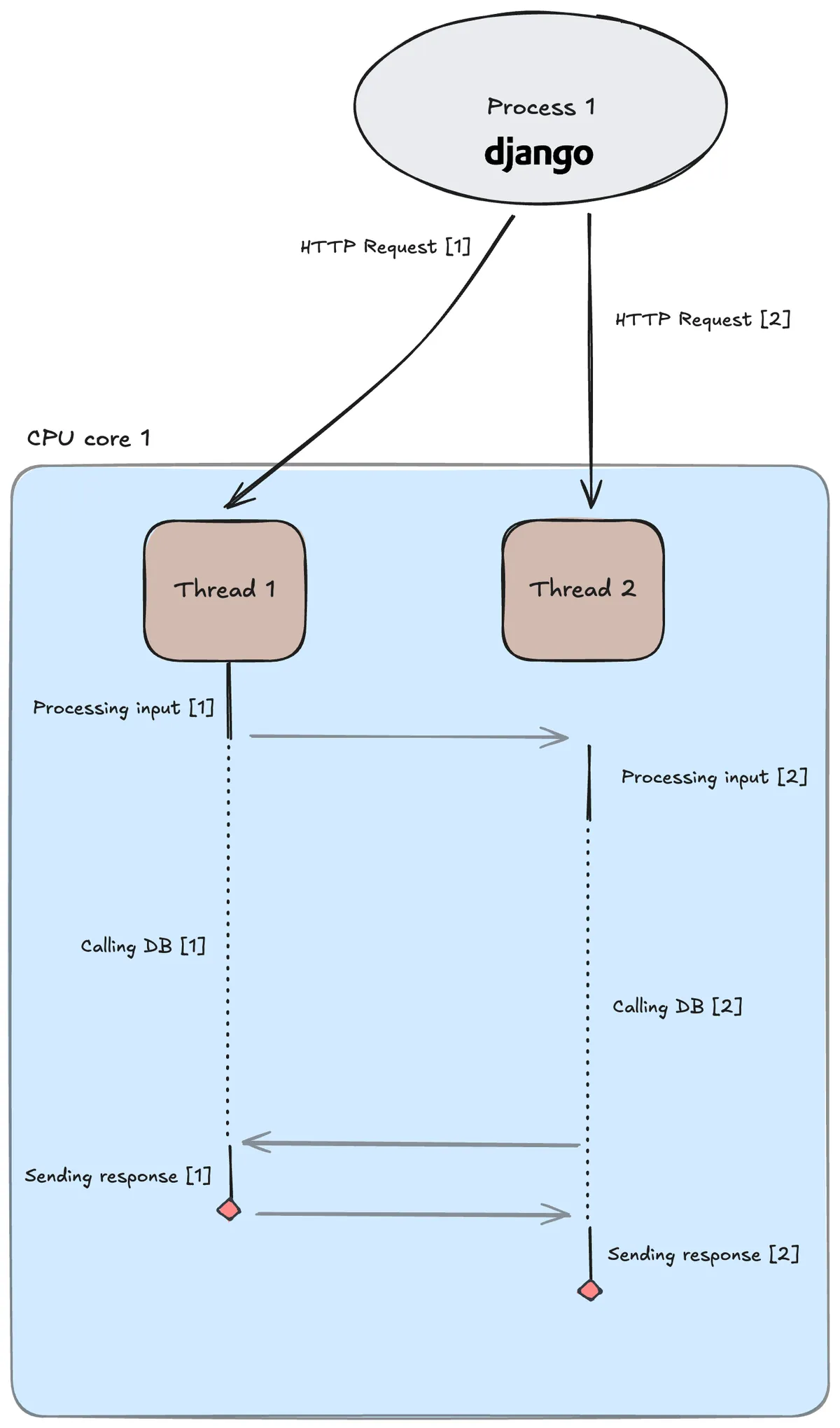

Django does this by creating another thread for the second request:

Figure 2: A multi-threaded Django app processing two requests concurrently. Each request is processed on its own thread.

The CPU core, which can only execute one instruction at a time, switches between threads depending on which isn’t blocked. This is much more efficient!

But what happens if our app needs to handle thousands of requests simultaneously? This is a common scenario for large-scale applications. In this case, our Django app would require a lot of threads, and we need to keep in mind that there is some overhead when switching between them.

The best approach here would be to write asynchronous code. This would allow a single thread to process requests concurrently.

Asynchronous FastAPI app

By writing asynchronous code and utilizing async/await, we can instruct the event loop on when an I/O call should be non-blocking, allowing the thread to return to the event loop and handle other requests.

We could rewrite our Django app to an async FastAPI app like this:

from fastapi import FastAPI, Query

import asyncio

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/currency/convert/")

async def convert(_from: str = Query(..., alias="from"), _to: str = Query(..., alias="to")):

from_currency = _from.lower()

to_currency = _to.lower()

rate = await convert_currency_io_bound(from_currency, to_currency)

return rate

async def convert_currency_io_bound(from_currency, to_currency):

await asyncio.sleep(5) # awaiting while the DB uses 5 sec to respond

if (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "gbp"):

return 0.75

elif (from_currency == "gbp" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.33

elif (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "eur"):

return 0.86

elif (from_currency == "eur" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.16

We start up our FastAPI backend with fastapi dev main.py and send two API calls to it at the same time:

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200 | 5.0846s

[2/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200 | 5.0843s

Total time: 5.0860s

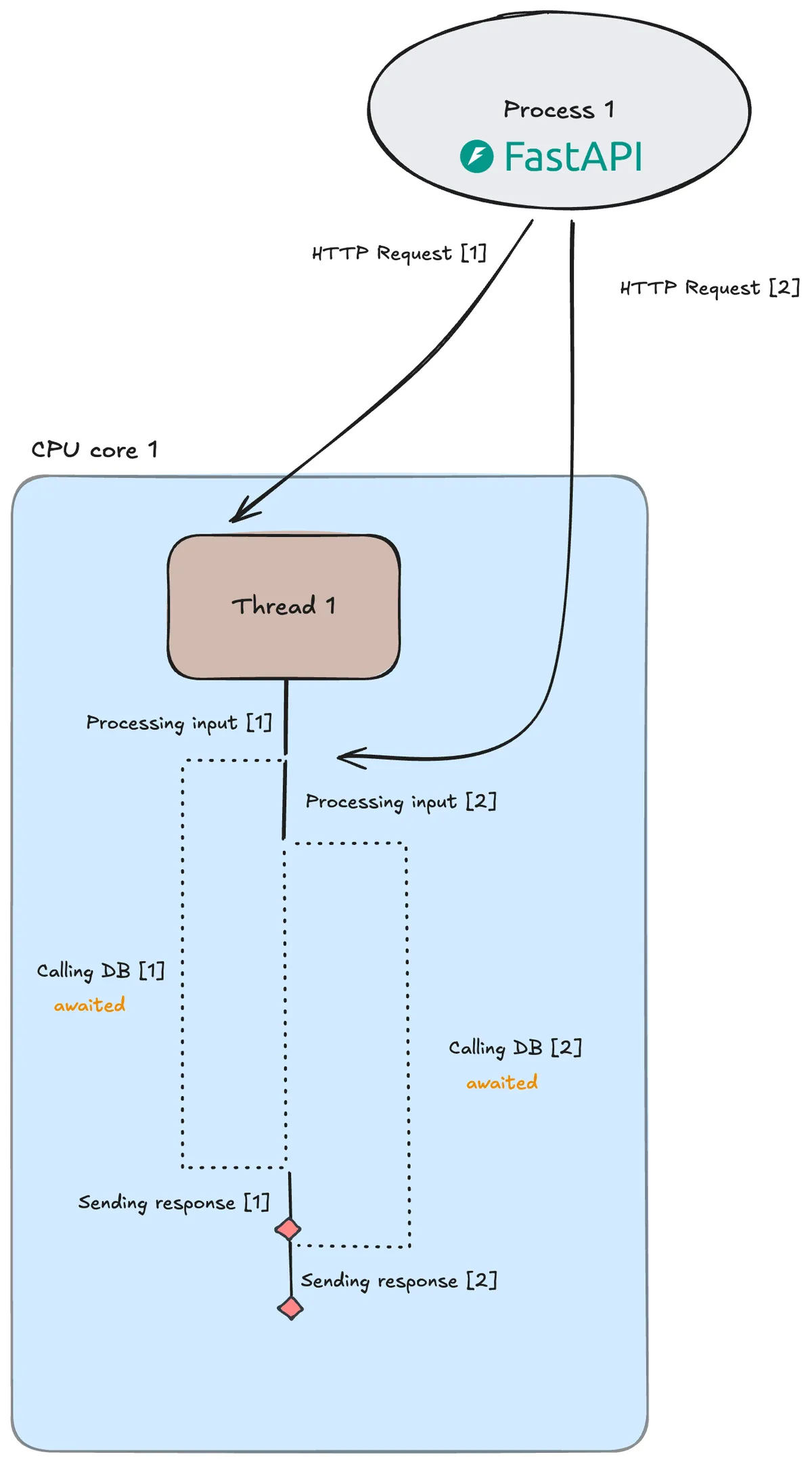

As expected, we see about the same performance as the multi-threaded Django app. However, both requests are handled by the same thread:

Figure 3: A single-thread FastAPI app processing two requests concurrently.

This is even more efficient than the multi-threaded Django app, as the CPU core doesn’t have the overhead of switching between threads!

The gains of async code become clearer the more simultaneous requests your backend handles. FastAPI is therefore a good choice for large-scale production applications that are I/O-bound.

What if our app isn’t I/O-bound?

In our example, the web API is I/O-bound. We are mostly just waiting for the DB to respond. But what happens if our application is CPU-bound? Let’s say our convert() method calls on a CPU-intensive method instead:

def convert_currency_cpu_bound(from_currency, to_currency):

# Do CPU-intensive work (finding primes up to a large number)

limit = 1_000_000

primes = []

for x in range(limit):

if is_prime(x):

primes.append(x)

if (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "gbp"):

return 0.75

elif (from_currency == "gbp" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.33

elif (from_currency == "usd" and to_currency == "eur"):

return 0.86

elif (from_currency == "eur" and to_currency == "usd"):

return 1.16

def is_prime(n):

if n < 2:

return False

for i in range(2, int(n ** 0.5) + 1):

if n % i == 0:

return False

return True

Well, creating multiple threads won’t help. A CPU core can only work on one thread at a time, and there isn’t much to gain by switching threads like in Figure 2.

An async backend isn’t helpful either, as there are no I/O calls to await.

Let’s start by seeing how fast a single-thread Django app (figure 1) now processes the requests:

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200 | 4.4099s

[2/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200 | 8.8472s

Total time: 8.8519s

As expected, the requests are processed sequentially. Now let’s run the same experiment but with a multi-threaded Django app (figure 2):

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200 | 9.2252s

[2/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200 | 9.2360s

Total time: 9.2367s

As expected, since there are no blocking calls, this doesn’t go any faster. In fact, we can see that multiple threads used more time than a single thread. This is most likely due to the overhead of switching between threads as both requests are processed concurrently.

The solution, for CPU-intensive apps, is to handle requests in parallel.

One would think that we could achieve this by running multiple threads of the same process across different CPU cores. This would be efficient, as threads are "cheaper" than processes.

Unfortunately, Python has an inherent restriction that only allows one thread to execute bytecode at a time. This is enforced through the GIL, which is a lock that threads share among themselves. Whichever thread holds the GIL can execute bytecode.

Multiprocessing Django app with Gunicorn

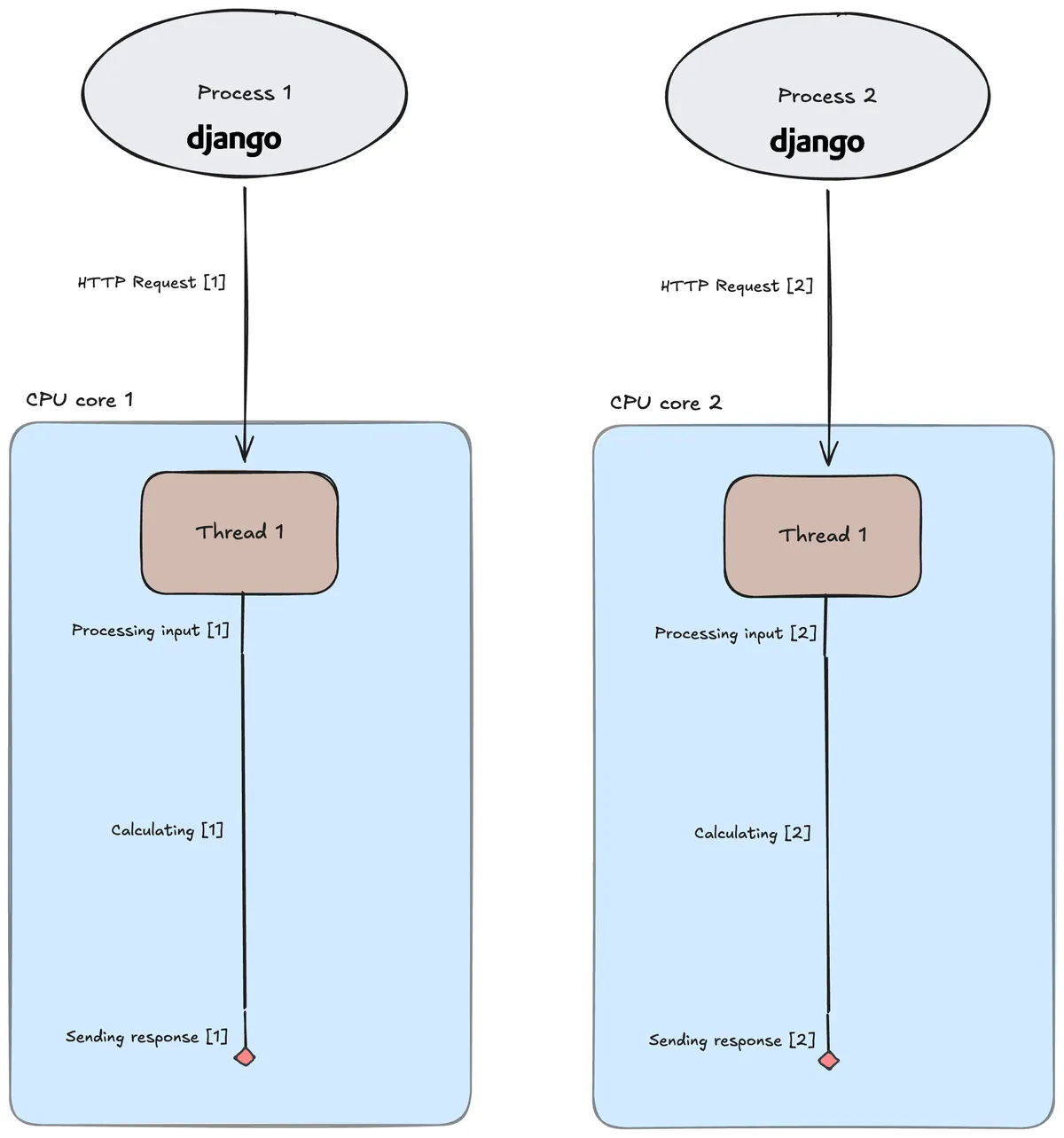

Therefore, the solution is to run our Django app in a web server with multiple workers (processes). Basically, we spin up our Django app multiple times as different processes. Each process has its own isolated memory space and GIL, and can run on its own CPU core. This way we sidestep the restriction posed upon threads, and can process multiple requests at the same time, in parallel.

We can do this with Gunicorn, which creates a web server that serves our Django app and takes care of HTTP requests and responses via the WSGI interface:

>> gunicorn --workers 2 --threads 1 banksite.wsgi:application

[0000-00-00 --:--:--] [39523] [INFO] Starting gunicorn 23.0.0

[0000-00-00 --:--:--] [39523] [INFO] Listening at: http://127.0.0.1:8000 (39523)

[0000-00-00 --:--:--] [39523] [INFO] Using worker: sync

[0000-00-00 --:--:--] [39525] [INFO] Booting worker with pid: 39525

[0000-00-00 --:--:--] [39526] [INFO] Booting worker with pid: 39526

This command starts a master process (in this example, PID 39523) that monitors the health of the two workers (PID 39525 and PID 39526) who actually process the incoming requests. Each worker is single-threaded, as in Figure 1, but could be set to be multi-threaded, as in Figure 2.

Let’s see how long it takes when we run our Django app with Gunicorn using two single-threaded workers:

>> python3 benchmark.py

Sending 2 concurrent requests...

[1/2] GBP->USD | resp=1.33 | status=200| 4.9159s

[2/2] USD->GBP | resp=0.75 | status=200| 4.9301s

Total time: 4.9310s

The requests are handled truly in parallel, and the total time is therefore the same as the time it takes to process a single request!

As mentioned, this is possible when running multiple processes, each running threads on its own CPU core:

Figure 4: A Gunicorn web server running two single-threaded Django app processes, both handling requests in parallel.

Conclusion

The most efficient use of your hardware depends on whether your Python app is I/O-bound or CPU-bound.

For I/O-bound applications, multithreading is a good approach as it allows for handling multiple requests concurrently. However, the best approach is to write async code as you avoid the overhead of switching between threads.

For CPU-bound applications, multiprocessing is the way to go.

All code and figures used in this post are available here.