We announced a public beta of Debusine repositories recently (Freexian blog, debian-devel-announce). One thing I’m very keen on is being able to use these to prepare “transitions”: changes to multiple packages that need to be prepared together in order to land in testing. As I said in my DebConf25 talk:

We have distribution-wide CI in unstable, but there’s only one of it and it’s shared between all of us. As a result it’s very possible to get into tangles w…

We announced a public beta of Debusine repositories recently (Freexian blog, debian-devel-announce). One thing I’m very keen on is being able to use these to prepare “transitions”: changes to multiple packages that need to be prepared together in order to land in testing. As I said in my DebConf25 talk:

We have distribution-wide CI in unstable, but there’s only one of it and it’s shared between all of us. As a result it’s very possible to get into tangles when multiple people are working on related things at the same time, and we only avoid that as much as we do by careful coordination such as transition bugs. Experimental helps, but again, there’s only one of it and setting up another one is far from trivial.

So, what we want is a system where you can run experiments on possible Debian changes at a large scale without a high setup cost and without fear of breaking things for other people. And then, if it all works, push the whole lot into Debian.

Time to practice what I preach.

Setup

The setup process is documented on the Debian wiki. You need to decide whether you’re working on a short-lived experiment, in which case you’ll run the create-experiment workflow and your workspace will expire after 60 days of inactivity, or something that you expect to keep around for longer, in which case you’ll run the create-repository workflow. Either one of those will create a new workspace for you. Then, in that workspace, you run debusine archive suite create for whichever suites you want to use. For the case of a transition that you plan to land in unstable, you’ll most likely use create-experiment and then create a single suite with the pattern sid-<name>.

The situation I was dealing with here was moving to Pylint 4. Tests showed that we needed this as part of adding Python 3.14 as a supported Python version, and I knew that I was going to need newer upstream versions of the astroid and pylint packages. However, I wasn’t quite sure what the fallout of a new major version of pylint was going to be. Fortunately, the Debian Python ecosystem has pretty good autopkgtest coverage, so I thought I’d see what Debusine said about it. I created an experiment called cjwatson-pylint (resulting in https://debusine.debian.net/debian/developers-cjwatson-pylint/ - I’m not making that a proper link since it will expire in a couple of months) and a sid-pylint suite in it.

Iteration

From this starting point, the basic cycle involved uploading each package like this for each package I’d prepared:

$ dput -O debusine_workspace=developers-cjwatson-pylint \

-O debusine_workflow=publish-to-sid-pylint \

debusine.debian.net foo.changes

I could have made a new dput-ng profile to cut down on typing, but it wasn’t worth it here.

Then I looked at the workflow results, figured out which other packages I needed to fix based on those, and repeated until the whole set looked coherent. Debusine automatically built each upload against whatever else was currently in the repository, as you’d expect.

I should probably have used version numbers with tilde suffixes (e.g. 4.0.2-1~test1) in case I needed to correct anything, but fortunately that was mostly unnecessary. I did at least run initial test-builds locally of just the individual packages I was directly changing to make sure that they weren’t too egregiously broken, just because I usually find it quicker to iterate that way.

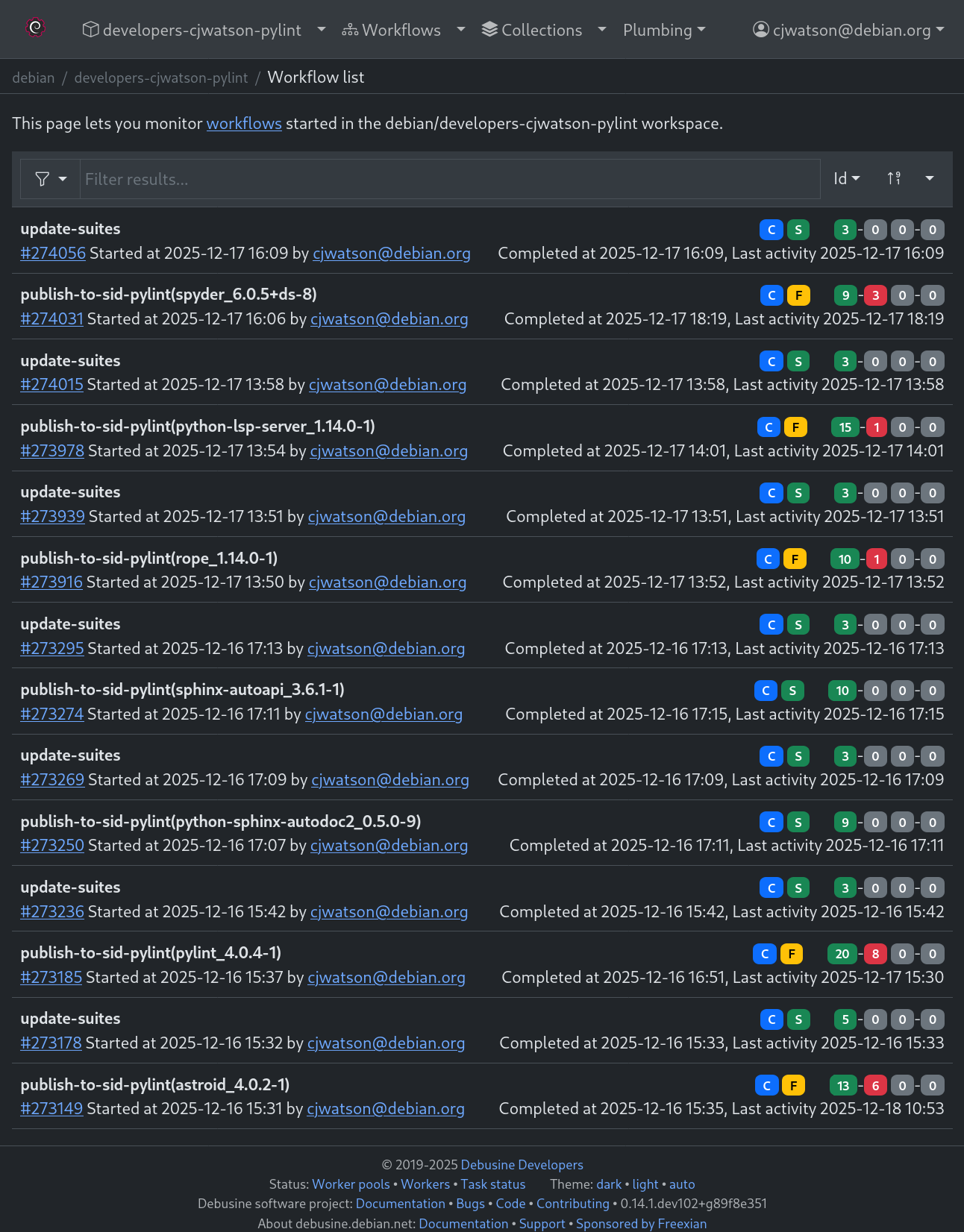

I didn’t take screenshots as I was going along, but here’s what the list of top-level workflows in my workspace looked like by the end:

You can see that not all of the workflows are successful. This is because we currently just show everything in every workflow; we don’t consider whether a task was retried and succeeded on the second try, or whether there’s now a newer version of a reverse-dependency so tests of the older version should be disregarded, and so on. More fundamentally, you have to look through each individual workflow, which is a bit of a pain: we plan to add a dashboard that shows you the current state of a suite as a whole rather than the current workflow-oriented view, but we haven’t started on that yet.

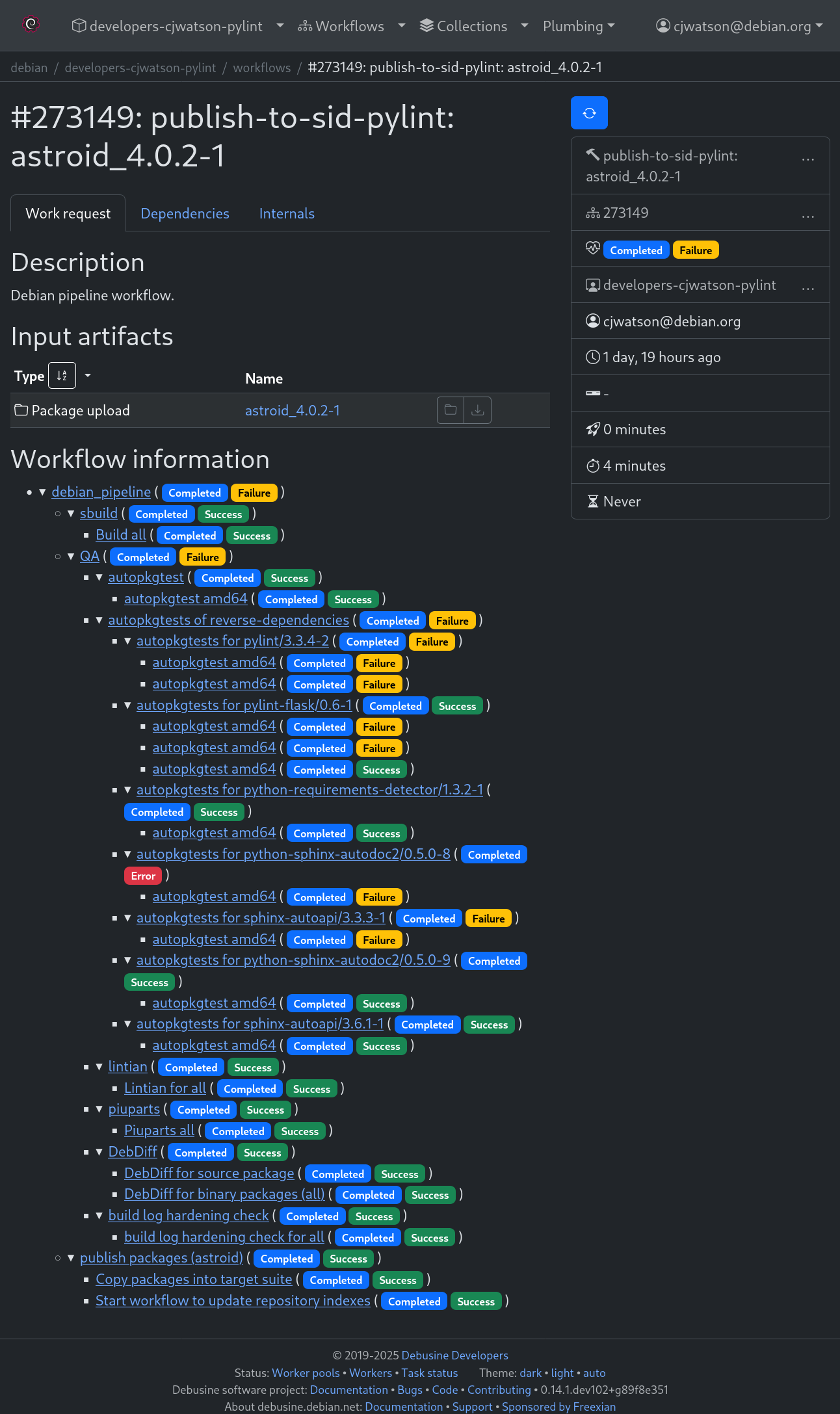

Drilling down into one of these workflows, it looks something like this:

This was the first package I uploaded. The first pass of failures told me about pylint (expected), pylint-flask (an obvious consequence), and python-sphinx-autodoc2 and sphinx-autoapi (surprises). The slightly odd pattern of failures and errors is because I retried a few things, and we sometimes report retries in a slightly strange way, especially when there are workflows involved that might not be able to resolve their input parameters any more.

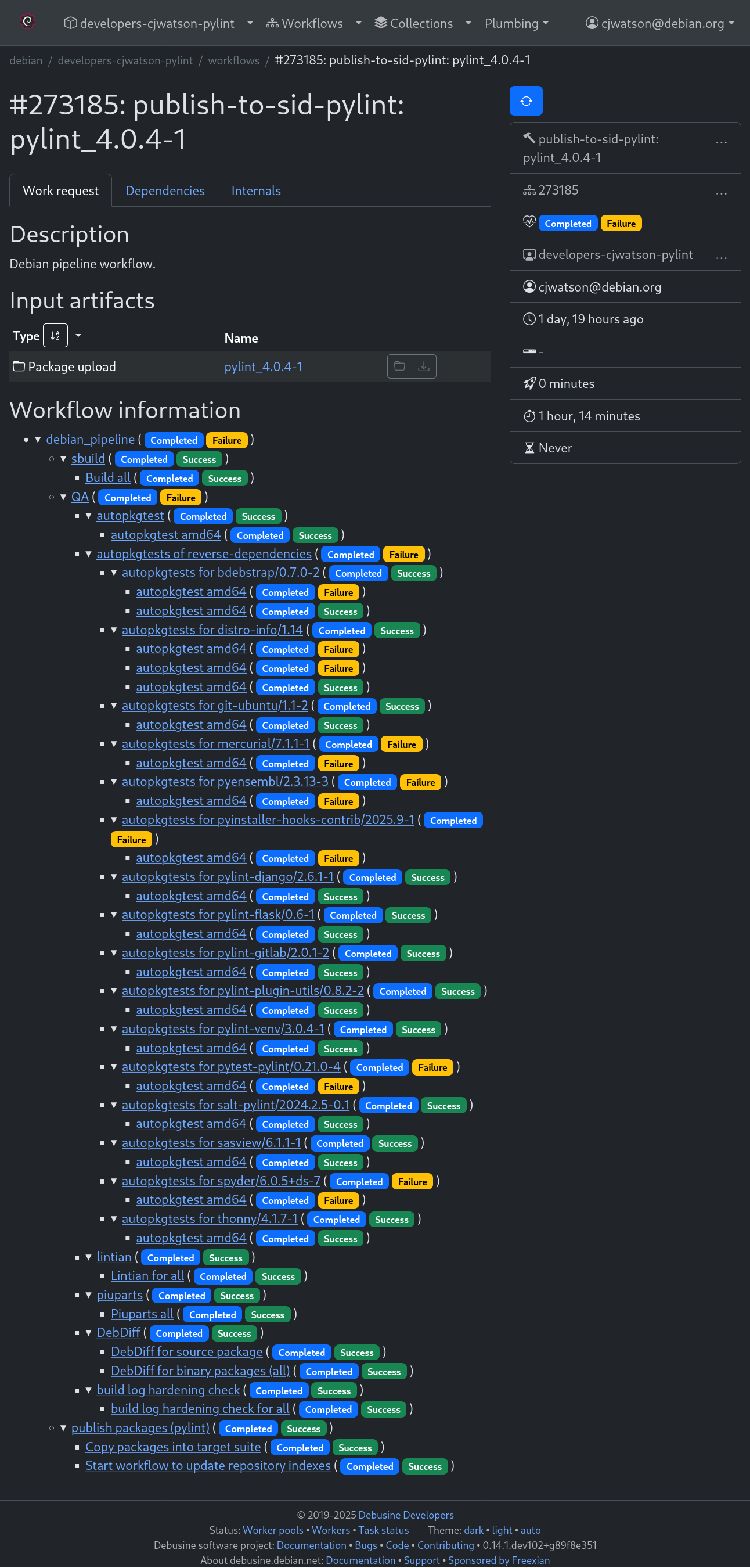

The next level was:

Again, there were some retries involved here, and also some cases where packages were already failing in unstable so the failures weren’t the fault of my change; for now I had to go through and analyze these by hand, but we’ll soon have regression tracking to compare with reference runs and show you where things have got better or worse.

After excluding those, that left pytest-pylint (not caused by my changes, but I fixed it anyway in unstable to clear out some noise) and spyder. I’d seen people talking about spyder on #debian-python recently, so after a bit of conversation there I sponsored a rope upload by Aeliton Silva, upgraded python-lsp-server, and patched spyder. All those went into my repository too, exposing a couple more tests I’d forgotten in spyder.

Once I was satisfied with the results, I uploaded everything to unstable. The next day, I looked through the tracker as usual starting from astroid, and while there are some test failures showing up right now it looks as though they should all clear out as pieces migrate to testing. Success!

Conclusions

We still have some way to go before this is a completely smooth experience that I’d be prepared to say that every developer can and should be using; there are all sorts of fit-and-finish issues that I can easily see here. Still, I do think we’re at the point where a tolerant developer can use this to deal with the common case of a mid-sized transition, and get more out of it than they put in.

Without Debusine, either I’d have had to put much more effort into searching for and testing reverse-dependencies myself, or (more likely, let’s face it) I’d have just dumped things into unstable and sorted them out afterwards, resulting in potentially delaying other people’s work. This way, everything was done with as little disruption as possible.

This works best when the packages likely to be involved have reasonably good autopkgtest coverage (even if the tests themselves are relatively basic). This is an increasingly good bet in Debian, but we have plans to add installability comparisons (similar to how Debian’s testing suite works) as well as optional rebuild testing.

If this has got you interested, please try it out for yourself and let us know how it goes!

Comments

With an account on the Fediverse or Mastodon, you can respond to this post. Since Mastodon is decentralized, you can use your existing account hosted by another Mastodon server or compatible platform if you don’t have an account on this one. Known non-private replies are displayed below.

Learn how this is implemented here.