a perfect storm

Volcanic eruptions in the mid-1340s triggered a chain of events that brought the Black Death to Europe.

Pieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague in medieval Europe. Credit: Public domain

The Black Death ravaged medieval Western Europe, ultimately wiping out roughly one-third of the population. Scientists have identified the bacterium responsible and its likely origins, but certain specifics of how and why it spread to Europe are less clear. According to a new paper published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, either one large volcanic eruption or a cluster of eruptions might have been the triggering factor, setting off a chain of event…

a perfect storm

Volcanic eruptions in the mid-1340s triggered a chain of events that brought the Black Death to Europe.

Pieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague in medieval Europe. Credit: Public domain

The Black Death ravaged medieval Western Europe, ultimately wiping out roughly one-third of the population. Scientists have identified the bacterium responsible and its likely origins, but certain specifics of how and why it spread to Europe are less clear. According to a new paper published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, either one large volcanic eruption or a cluster of eruptions might have been the triggering factor, setting off a chain of events that brought the plague to the Mediterranean region in the 1340s.

Technically, we’re talking about the second plague pandemic. The first, known as the Justinian Plague, broke out about 541 CE and quickly spread across Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. (The Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I, for whom the pandemic is named, actually survived the disease.) There continued to be outbreaks of the plague over the next 300 years, although the disease gradually became less virulent and died out. Or so it seemed.

In the Middle Ages, the Black Death burst onto the scene, with the first historically documented outbreak occurring in 1346 in the Lower Volga and Black Sea regions. That was just the beginning of the second pandemic. During the 1630s, fresh outbreaks of plague killed half the populations of affected cities. Another bout of the plague significantly culled the population of France during an outbreak between 1647 and 1649, followed by an epidemic in London in the summer of 1665. The latter was so virulent that, by October, one in 10 Londoners had succumbed to the disease—over 60,000 people. Similar numbers perished in an outbreak in Holland in the 1660s. The pandemic had run its course by the early 19th century, but a third plague pandemic hit China and India in the 1890s. There are still occasional outbreaks today.

The culprit is a bacterium called Yersinia pestis, and it’s well known that it spreads among mammalian hosts via fleas, although it only rarely spills over to domestic animals and humans. The Black Death can be traced to a genetically distinct strain of Y. pestis that originated in the Tien Shan mountains west of what is now Kyrgyzstan, spreading along trade routes to Europe in the 1340s. However, according to the authors of this latest paper, there has been little attention focused on several likely contributing factors: climate, ecology, socioeconomic pressures, and the like.

The testimony of the tree rings

Taking tree samples from the Pyrenees. Credit: Ulf Büntgen

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time,” said co-author Ulf Büntgen of the University of Cambridge. “What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they? Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history? It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no one can answer alone.”

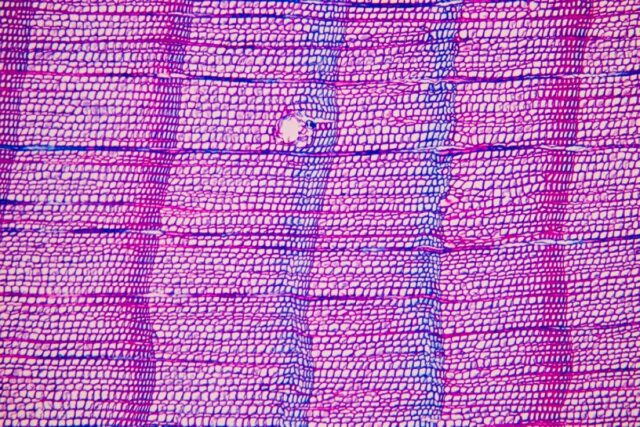

Büntgen et al. collected core and disc samples from both living and relict trees at eight different European sites to reconstruct summer temperatures for that time period. They then compared that data with estimates of sulphur injections into the atmosphere from volcanic eruptions, based on geochemical analyses of ice core samples collected from Antarctica and Greenland.

They studied a wide range of written sources across Eurasia—chronicles, treatises, historiography, and even a bit of poetry—looking for mention of atmospheric and optical phenomena linked to volcanic dust veils between 1345 and 1350 CE. They also looked for mentions of extreme weather events, economic conditions, and reports of dearth or famine across Eurasia during that time period. Information about the trans-mediterranean grain trade was gleaned from administrative records and letters.

Close-up of tree ring samples taken from the Pyrenees, showing the telltale “blue rings.” Credit: Ulf Büntgen

The tree ring data enabled Büntgen et al. to determine that there had been a volcanic eruption (or a cluster of eruptions) around 1345, specifically so-called “blue rings” that indicate unusually cold or wet summers—in this case, for three consecutive years (1345, 1346, and 1347). The textual sources also referenced details like an unusually high degree of cloudiness and darkened lunar eclipses, indications of the after-effects of volcanic activity.

That colder climate in turn led to widespread crop failures and associated famine, particularly in parts of Spain, southern France, Egypt, and northern and central Italy. While Milan and Rome were largely self-sufficient, per the authors, smaller urban centers like Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Siena, and Venice relied on a complex grain supply system to import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde via established trade routes along the Black Sea coast. Textual evidence supports this, showing substantial price hikes for cereals and the imposition of grain trade regulations in 1346. This saved people from starvation but also brought Y. pestis along for the ride, with devastating consequences.

Per the authors, while the factors that triggered the spread of the Black Death to Europe are unique, the study illustrates the risks of a globalized world and calls for a similar interdisciplinary approach to future threats. “Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globaliszd world,” said Büntgen. “This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with COVID-19.”

DOI: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025. 10.1038/s43247-025-02964-0 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.