When working with agentic AI, tool calls and results abound. With tokens quicky mounting up, it’s common to want to visualise them, with the obvious solution being websites like OpenAI’s. However, using these with any more than toy data raises serious data privacy concerns. Consequently, I set out to make my own, more secure, offline solution.

Background

I feel I ought to explain what a token is before anything else: A token is a portion of text, generally sub-word. Given neural networks much prefer working with numbers, each token is mapped to a distinct ID and a sequence of them passed to a model for it to process.

When it comes to language models, tokenisers are usually trained alongside. They look at the same training data, but inst…

When working with agentic AI, tool calls and results abound. With tokens quicky mounting up, it’s common to want to visualise them, with the obvious solution being websites like OpenAI’s. However, using these with any more than toy data raises serious data privacy concerns. Consequently, I set out to make my own, more secure, offline solution.

Background

I feel I ought to explain what a token is before anything else: A token is a portion of text, generally sub-word. Given neural networks much prefer working with numbers, each token is mapped to a distinct ID and a sequence of them passed to a model for it to process.

When it comes to language models, tokenisers are usually trained alongside. They look at the same training data, but instead of learning about the meaning, they focus on splitting the corpus into chunks: tokens. The output of this is a vocabulary, with which the language model can read and write. There are also often special characters added to indicate the start and end of generation, as well as unknown character sequences not found in the tokeniser training.

The main reason for tokenising, and not just splitting text at the character or word levels, is efficiency. By tokenising, you can represent many different permutations of words, characters, and punctuation marks without having a vocabulary in the millions (Meta’s Llama 3.2 models have vocabularies of size around 128,000).

Whilst tokens may be more efficient, they are not without their drawbacks. An oft joked about example of language models failing at a simple task is counting the number of repeated letters in a phrase:

How many of the letter r may be found in the word ‘strawberry?’

The eagle-eyed among you will notice the answer is 3. However, even the most advanced LLMs of the day regularly claim otherwise - and this is almost all down to tokenisation. For example, GPT-4 does not see ‘strawberry’ as ‘S-T-R-A-W-B-E-R-R-Y,’ but instead ‘STR-AW-BERRY.’

It cannot ‘see’ the letters individually, so it is difficult for it to count them correctly.

These oddities highlight precisely why we cannot simply treat LLM input as plain text - as we see it. To build robust AI systems, we need to look under the microscope and see the text exactly as the model does. This need for transparency returns us to the project at hand.

What

The core aim was to produce a simple interface that I could start up locally, have tokenisers automatically downloaded, and then see the distinction between tokens via coloured highlighting, much like OpenAI has on their site.

In particular, I wanted a CLI-based solution for ease of use that would support both live typing/updating and passing whole strings/files at once.

How

tiktoken is the Python SDK which allows access to tokenisers for OpenAI models such as GPT-4o, GPT-5 etc., however it is purely a library for encoding and decoding programmatically - its output is not readily human-readable. Therefore, I decided to use Python as the language for my application, wrapping the backend logic of tiktoken with a visual interface better suited for analysis by a person.

Separating

The first step was to implement text tokenisation. Luckily, tiktoken provides a friendly API to do this. To fetch a tokeniser for a particular model is simple:

from tiktoken import encoding_for_model

tokeniser = encoding_for_model("gpt-4")

This looks up the corresponding tokeniser, and downloads and installs it. Next, we can tokenise a string via encode, separate the tokens, and then decode each individually.

input_text = "Hello, World!"

encoded_text = tokeniser.encode(input_text)

decoded_tokens = [tokeniser.decode_single_token_bytes(raw_token) for raw_token in encoded_text]

string_tokens = [bytes_to_string(token) for token in decoded_tokens]

def bytes_to_string(item: bytes) -> str:

return item.decode("utf-8", errors="replace")

This allows us to see where the token boundaries lie.

However, you may wonder why bytes_to_string uses errors="replace" when moving from bytes to str. When tokenisers are trained, the token boundaries do not necessarily completely encompass multi-byte characters (e.g. emojis or non-English languages). Therefore, making sure that the decoding process is robust to such quirks is essential.

Displaying

For the CLI, I went with click to define the various flags and arguments available. The options include:

text: What to tokenise. If not included then prompts to enter text, or reads from stdin.

-m`–model: The model to use e\.g\. gpt-5\. Default is gpt-4`.

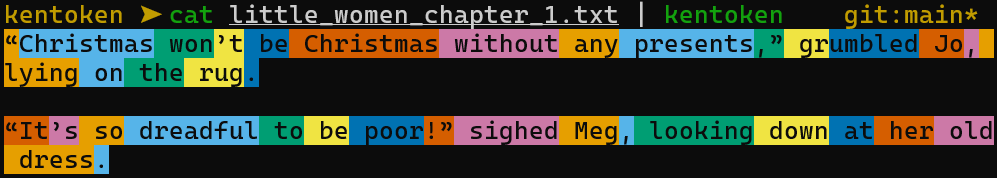

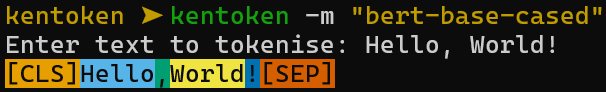

With the tokens separated and decoded, I applied a colour cycle to the output. The resulting CLI looks like this:

This works as I had envisioned, so now it is time to move on to the reactive aspect. I decided to go with the textual TUI package to facilitate this. The API was straightfoward and easy to use and now when you pass -i or --interactive then you see:

At present, only 3 ‘statistics’ are displayed, but I have plans to add more which would aid in tokenised input analysis.

Extension

With these features, the application had reached MVP status. However, I saw an avenue for improving upon its capabilities: supporting any tokeniser available from HuggingFace. The change to allow this was small, given the API for the tokenizers library is relatively similar to that of tiktoken. This change expanded the horizons of the application massively and allowed for seeing how thousands of open-source models approach tokenisation, which is often very different to OpenAI:

Conclusion

This was a quick and simple project which will not only prove useful to me, but through which I also learnt a lot. Given it is complete (for now), it deserves a name: kentoken. If you feel that it could help you, then feel free to try it out here.