I moved the documentation of my free programs from MkDocs to ddoc.

Here’s why.

Why I had to give up with MkDocs

Ten years ago, I started using MkDocs.

The first experience was very good: with a tiny configuration and my own Markdown files, I could immediately get a site working.

Making it look like I wanted was more painful than it should have been, because the themes and their stylesheets aren’t really consistent. But it wasn’t a terrible experience, it worked.

And when I modified the pages, and added ones, I could easily update the site.

But every few years, on changing computer or system, installing MkDocs was really a terrible experience. I had to spend hours dealing with modified HTML and modified themes, full of messy CSS rules and !important, to try simply keep…

I moved the documentation of my free programs from MkDocs to ddoc.

Here’s why.

Why I had to give up with MkDocs

Ten years ago, I started using MkDocs.

The first experience was very good: with a tiny configuration and my own Markdown files, I could immediately get a site working.

Making it look like I wanted was more painful than it should have been, because the themes and their stylesheets aren’t really consistent. But it wasn’t a terrible experience, it worked.

And when I modified the pages, and added ones, I could easily update the site.

But every few years, on changing computer or system, installing MkDocs was really a terrible experience. I had to spend hours dealing with modified HTML and modified themes, full of messy CSS rules and !important, to try simply keep the same style.

As I looked around, I noticed I wasn’t the only one. People were forking themes, or making new ones (they’re complex) just to keep their styles.

Some might suggest pinning theme versions to avoid breakage. While this prevents surprise breakages during reinstallation, it creates a different problem: you’re frozen in time, unable to benefit from updates, and the breaking changes are simply waiting for you when you eventually need to upgrade.

More fundamentally, neither pinning nor other theme maintenance best practices address the core issue — that customizing themes requires understanding and fighting against injected CSS and HTML structures you don’t control.

Updating markdown files and deploying them as a static site should be a strong reliable process, not one that you have to maintain.

MkDocs is optimized for a good initial experience but didn’t really work for me in the long term. It was innovative, really did help me, but it was time to let it go.

MkDocs isn’t broken, the approach is. Or rather, it’s not suitable for the needs of a simple documentation site.

I mentioned MkDocs, which I used, but the problem of theme maintenance and CSS injection is common to all SSGs I’ve seen. It’s the same for Docusaurus, Sphinx, Jekyll, etc.

Another kind of solution: Zola (and similar)

Static site generators are older than MkDocs, they’re older than the Markdown brand (many people were doing things similar to Markdown before it got given a name, and also generating HTML).

So in the last 20 or 30 years, I tried a lot of generators, some good, some bad.

This blog that you’re reading is of course statically generated.

The current occurrence is based on Zola, and I must confess that I didn’t have the problem I had with Mkdocs: when reinstalling Zola, nothing broke. My site was still the same. And from what I gather from its structure, breakages should be rather limited on version changes.

Overall, I’m quite happy with Zola for my blog.

While it was obviously designed with blogs in mind, Zola is generic enough to accommodate documentations.

But this would involve too much work with templates. Even making a simple blog requires way too much work in many template files and stylesheets.

Software documentation sites are simple, they shouldn’t need messing with templates and fighting CSS stylesheets designed for other uses, or for more global ones.

That wasn’t the experience I was looking for.

What I really wanted, what I made

The experience I was after for making sites like the one of broot or bacon was a straightforward one.

I don’t need much templating because what I want for documentation sites is always

- a site-wide menu (pure CSS can decide its layout and look)

- a page Table of Content (pure CSS can again decide the details)

- easy addition of logos, external links, most often in the header or footer

- links, anchors, images, etc. managed

- a search function, links to previous/next pages if you want them

- additional CSS files and JS scripts directly included with no configuration needed

All this, being standard, doesn’t need templating.

The rest is just applying best practices to ensure it works as expected, nothing breaks too easily, bad links are displayed, etc.

Most importantly, zero CSS or complex or surprising HTML layout must be injected by the tool.

There’s a default CSS, which makes it easy to start, but once you change it, it’s not replaced and no other CSS file is injected which would change the style.

With ddoc, it was easy to port all my sites and get exactly the look I wanted for each of them.

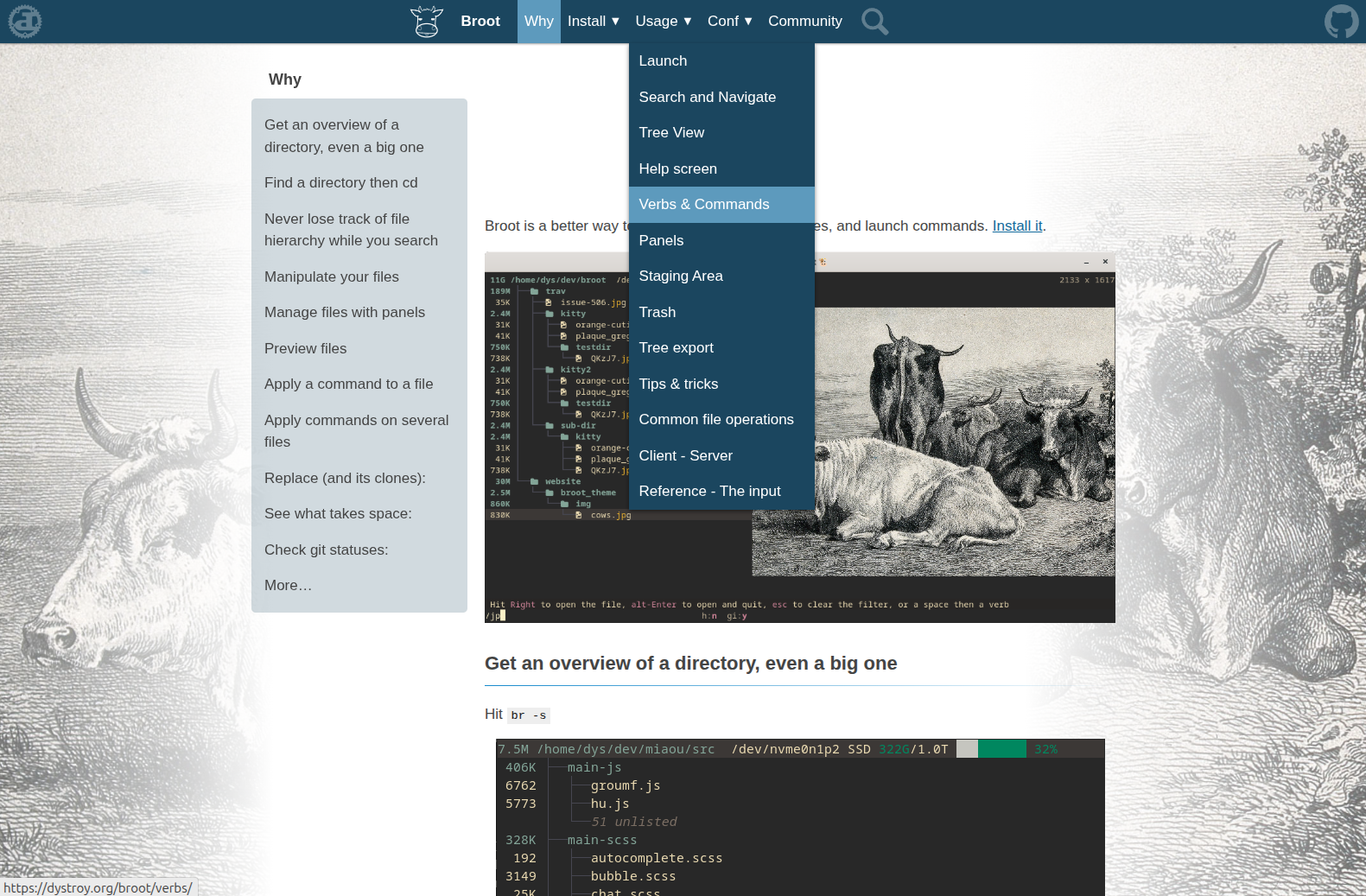

Here’s how one of them looks like:

(more examples on ddoc’s example page)

The experience you get with ddoc

ddoc isn’t suitable for all needs.

It’s tailored for documentation sites, and you should not even try to use it for your blog, album, etc. (at least not the current version).

But if you use it for the kind of documentation that I make for my programs and that I most often observe, I think it can be very simple and satisfying.

ddoc is a single binary with no dependencies — no Python environment, no npm packages, no theme downloads. The search function is included and requires no configuration.

- you start your new site with

ddoc --init - you edit a configuration file, similar to the one of MkDocs, except it doesn’t refer to scripts, plugins, themes, etc.

- you add some Markdown files

- you launch

ddoc --serveto observe your site and your changes - then you only have to edit your CSS file, which won’t be broken by other moving parts

All internal links are relative, ddoc doesn’t need to know the base url of the site. No problem deploying or moving the site.

Years, later, you should still be able to add Markdown files and images, edit the existing files, and still get an unchanged look, even if you changed computer or OS many times in between.

If a new feature coming later to ddoc requires a CSS change, you’ll probably have to change your CSS to use it, but it will be opt-in and the existing configuration and sources will still work with the new version of ddoc. That’s the philosophy of the tool.

Check it out: https://dystroy.org/ddoc and tell me what you think.