We wanted to come up with a practical guide on how to implement a secure and hardened MCP server—or, in reality, any API server. Not surprisingly, they are technically very identical. However, in an era where "users" are increasingly autonomous agents and backends are being wrapped in Model Context Protocol (MCP) layers, the attack surface has shifted to the client side too. To build any resilient system, developers must move beyond the basics of writing secure code (which is a challenge by itself) and address how the architecture and infrastructure are designed as well.

While you should always tailor your defenses to your specific threat model, there are certain universal "must-haves" for any secure system, let’s go.

The MCP Frontier

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) c…

We wanted to come up with a practical guide on how to implement a secure and hardened MCP server—or, in reality, any API server. Not surprisingly, they are technically very identical. However, in an era where "users" are increasingly autonomous agents and backends are being wrapped in Model Context Protocol (MCP) layers, the attack surface has shifted to the client side too. To build any resilient system, developers must move beyond the basics of writing secure code (which is a challenge by itself) and address how the architecture and infrastructure are designed as well.

While you should always tailor your defenses to your specific threat model, there are certain universal "must-haves" for any secure system, let’s go.

The MCP Frontier

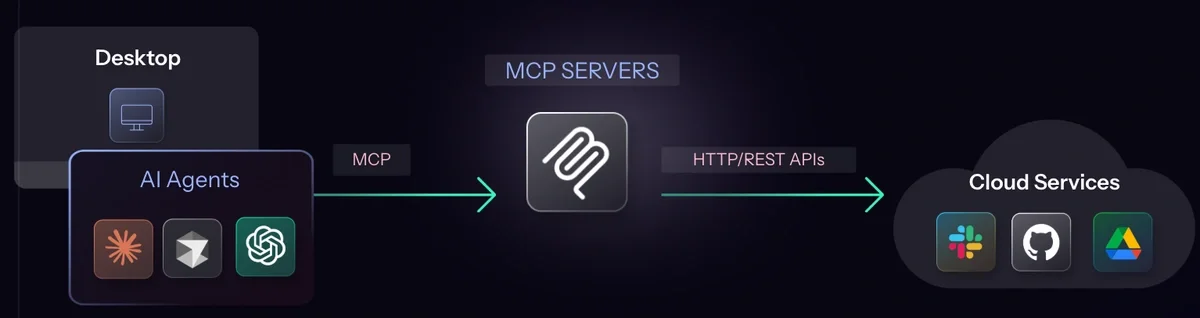

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) connects LLMs to your data and accounts. There are two types of MCP servers as we see it - Thin Wrappers vs. Standalone Servers.

For standalone MCP servers, the golden rule is to design tools with an API-first mindset, applying the below 5 pillars across the board. If you are integrating a** third-party server**, prioritize a ‘passthrough’ architecture. Minimize the logic within your wrapper to reduce the attack surface and ensure security integrity.

Security by Design: The Foundation

Security is now more critical than ever. In the age of AI, autonomous agents can be turned into bitter adversaries, scanning your APIs for vulnerabilities and executing exploits at machine speed. To counter this and before jumping to actual guidelines let’s hit the foundation first, we must build following "Security by Design" principles:

Never Trust Anything: You cannot know who the client is or what their intent is. Therefore, every single piece of data—headers, parameters, and bodies—must be verified and sanitized. 1.

Least Privilege: Every process and user should only have the minimum permissions necessary to perform its job. This is vital to contain the "blast radius" if a breach occurs. 1.

Multi-Layered Defense (Defense in Depth): No single measure is enough. We use WAFs, activity monitoring, sandboxing, and non-root permissions. Layering defenses slows down adversaries and provides multiple opportunities to fully stop a takeover.

- Segregate/Isolate Assets: Architecture matters. Logically divide your sub-systems so that a compromise in one sub-system/machine doesn’t grant access to the whole puzzle. This applies to data (don’t put everything in one "users table") and file systems (uploads should go to a system-controlled directory where they cannot be executed).

Continuous Updates: Security is a moving target. Always keep your libraries, packages, OS, and server frameworks up to date to patch known vulnerabilities before they are exploited. 1.

The Backend is the Last Frontier: Developers often sanitize user input like name/email, etc, in the frontend browser and assume they are safe. This is a dangerous fallacy. Adversaries bypass your UI and hit your APIs directly. Your backend must verify everything as if the frontend doesn’t exist.

Most developers don’t overlook security intentionally; they simply haven’t been introduced to these specific principles. There is a reason cybersecurity has become its own dedicated field. However, with your experience in backend development, you’ll find these concepts very intuitive to pick up.

Our Own Secure Architecture of MCPTotal.io

As you begin to internalize these guidelines, it’s worth noting that we’ve applied these exact principles to our own architecture. This foundational security is what allows us to safely offer high-trust features, such as letting customers run their own MCP servers and custom code directly within our backend.

Our philosophy is to: assume ‘breached’. When we design a system, we ask ourselves, assuming this component is breached, what an adversary can do and how far can they get.

You can learn more about real security and how we look at it from reading other blog posts. For example, the fact that we use a token vault to store customer credentials securely, where we talk further about other security principles related data storage. Or you can read more about our general backend architecture here.

Local vs External Threats

One final note before we dive in. Many MCP developers begin by building a simple STDIO server that runs locally on their own machine. That approach is perfectly reasonable. However, it’s important to recognize that the threat model for a local server is fundamentally different from that of a server exposed to the internet.

In a local setup, it’s often acceptable to make assumptions about how the server is used and to largely ignore external interactions, which are minimal to-non-existent unless the server explicitly accesses online resources. Problems arise when a server originally designed for local use is later deployed as a public-facing service. At that point, those assumptions no longer hold, and previously acceptable shortcuts can become serious security issues.

Keep this distinction in mind when building an MCP server that will be accessible over the internet.

Also, be mindful of binding your server to 0.0.0.0, which many MCP SDKs do by default. This is generally a bad idea, as it allows any device on your local network to connect to the server—potentially enabling unauthorized access to your data or the execution of actions on your behalf.

From a technical standpoint, binding to 0.0.0.0 means the socket listens on all network interfaces, including those exposed to other machines. In most cases, this behavior is unintended and introduces unnecessary risk. The fix is simple, bind to 127.0.0.1 or use STDIO.

Part 1: The 5 Pillars of API Hardening

1. Identity & Ownership: The Mandatory Baseline

Mandatory Authentication: All endpoints must check for authenticated users. Use centralized middleware to enforce token validation (JWT, OAuth2) across the entire API surface.

Resource Ownership (BOLA/IDOR): Authentication proves who a user is; Authorization proves what they can do. Broken Object Level Authorization is when the system can access everything, but it doesn’t enforce the scope to the logged in user, that’s a big issue, causing an attacker to access resources of another user. This is easy to overlook, each API must check ownership of everything first.

The Rule: For example, in database, every query must be "scoped." Never fetch a resource by its ID alone (unless it’s a global data resource).

Secure Query: SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = $order_id AND user_id = $authenticated_user_id

2. Input Integrity: Sanitization & Business Logic

All parameters of your APIs must verify input for correctness, better drop requests if input doesn’t make sense. Sometimes you can sanitize some bad characters or inputs too, but that’s the least preferred method (it can create some issues on its own).

Strings (The HTML/XSS Trap): Attackers provide names containing malicious scripts (e.g., <script>...</script>). If stored raw, any dashboard rendering this name will execute the script (Stored XSS).

Integers (Type Enforcement): Prevent quantity manipulation (e.g., quantity: -1).

File Paths (Directory Traversal): Prevent access to system files (e.g., filename: "../../../etc/passwd").

The "Price" Rule: Never accept a price from the client. The server must look up the price in its own database based on a product_id. Remember, don’t trust stuff coming from the client side, definitely not things that the system should find in a ‘source of truth’ location.

3. Resource Handling: SSRF and File Logic

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF): This makes your server a trusted proxy to attack your internal network or cloud metadata services. Must check and verify URLs correctly, it’s tricky by itself.

The Zip Bomb: Tiny archives that expand into gigabytes to crash your server (DoS). So set your quotas correctly to avoid this stuff, check file sizes, etc.

Secure File Uploads: Rename every file to a GUID and store them in a fixed directory that the system controls which the outside world doesn’t have direct HTTP access to. Never run or execute files from this directory to avoid an adversary taking over your backend. Remember the segregation principle.

4. Hardening the Runtime: Isolation

Run as "Nobody": Never run your server as root or admin. If hijacked, the attacker’s permissions are severely limited. This can also go to remove envars that aren’t used anymore that might contain sensitive data like credentials.

Tenant Isolation: Ensure one customer’s data is logically separated from another’s, that requires a whole DB schema design, most developers might overlook this because it requires extra work.

Network Lockdown: Close SSH (Port 22) to the public internet, seriously. Use a VPN to access your back-office server. Don’t mix it with your own public facing server, or make sure it’s super secure, but you just opened more attack surface to the world and it will be used against you.

5. Metrics & Network Observability

Seriously, make sure you have logs recorded somewhere. They only come handy when you need them. Post-mortem and diagnostics are only one reason, runtime security is another...

Performance Baselines: Monitor CPU and Memory. A spike without a traffic increase often indicates a compromise, such as a hidden crypto-miner.

Network Traffic: Watch for deviations in network egress. If your server sends data to unknown external IPs or too much data outside, it’s a sign of a breach.

WAF: Deploy a Web Application Firewall to block attack patterns before they hit your code. It saved the day with the lethal react2shell bug recently.

Part 2: Related Security Concerns

1. The Inversion of Trust: Malicious MCP Servers

In MCP, the user fears the server. A malicious server can return results designed to perform Indirect Prompt Injection on an Agent, tricking it into running commands like rm -rf /. And there’s no good cure around, you will need an MCP gateway to filter it.

2. The "Plaintext JSON" Secret Problem In The Endpoint

Users who use agents, normally configure and store API keys in plaintext JSON files. This is the (terrible) standard today. Use a password manager.

3. BOLA & Input Verification in MCP

To re-iterate: if your MCP server is a simple wrapper, you are essentially delegating the heavy lifting of security to the underlying API server. In that case, you must trust that the API server is rigorously performing input verification and enforcing the principles we’ve discussed. If it isn’t, or if you are building a standalone MCP, that responsibility falls entirely on you.

If you choose a dual architecture—splitting your system into an MCP wrapper and a dedicated API server—place your primary defenses within the API server. This centralizes your security logic and protects you against internal threats; even if a malicious actor gains access to your internal network, they could attempt to bypass the MCP layer and connect to your API servers directly.

4. If you’re building a thin-wrapper MCP server for existing APIs, here’s a couple of things to note:

- API Key Management: If your MCP server holds credentials for connecting to cloud services, implement strict tenant isolation to prevent cross-client data leakage. Furthermore, ensure all API keys are stored securely within a dedicated token vault. Normally the API key would fully come from the AI agent, so you wouldn’t want to cache it permanently or store it on disk as is.

The Caching Trap: Naive caching is both a security and privacy nightmare. If you cache data for User A and serve it to User B, you have a major data leak. But the fact you cache data in one more place now might violate your own privacy policies. Isolate caches by identity per user.

Conclusion

Securing a server isn’t a mystery; it’s about fanatical verification of input at the code level and solid architecture to reduce blast reduce. If you validate inputs, check ownerships, and run a least-privilege environment, you’ve won most of the battle. However, the "missing if-statement" remains our greatest enemy. In today’s interconnected ecosystem, even generic features can be turned into weapons. Look no further than MongoBleed—a critical memory leak triggered by one missing integer check. To protect your data and your sanity, remember: never trust an input you haven’t verified.