A description of advanced tips and tricks for effective Internet research of papers/books, with real-world examples.

Over time, I developed a certain google-fu and expertise in finding references, papers, and books online. I start with the standard tricks like Boolean queries and keyboard shortcuts, and go through the flowchart for how to search, modify searches for hard targets, penetrate paywalls, request jailbreaks, scan books, monitor topics, and host documents. Some of these tricks are not well-known, like checking the Internet Archive (IA) for books.

I try to write down my search workflow, and give general advice about finding and hosting documents, with [demonstration case studies](https://gwern.net/search-case-studies “‘Internet Search Tips § Case Studies’, Gwern 2018”…

A description of advanced tips and tricks for effective Internet research of papers/books, with real-world examples.

Over time, I developed a certain google-fu and expertise in finding references, papers, and books online. I start with the standard tricks like Boolean queries and keyboard shortcuts, and go through the flowchart for how to search, modify searches for hard targets, penetrate paywalls, request jailbreaks, scan books, monitor topics, and host documents. Some of these tricks are not well-known, like checking the Internet Archive (IA) for books.

I try to write down my search workflow, and give general advice about finding and hosting documents, with demonstration case studies.

Google-fu search skill is something I’ve prided myself ever since elementary school, when the librarian challenged the class to find things in the almanac; not infrequently, I’d win. And I can still remember the exact moment it dawned on me in high school that much of the rest of my life would be spent dealing with searches, paywalls, and broken links. The Internet is the greatest almanac of all, and to the curious, a never-ending cornucopia, so I am sad to see many fail to find things after a cursory search—or not look at all. For most people, if it’s not the first hit in Google/Google Scholar, it doesn’t exist. Below, I reveal my best Internet search tricks and try to provide a rough flowchart of how to go about an online search, explaining the subtle tricks and tacit knowledge of search-fu.

Roughly, we need to have proper tools to create an occasion for a search: we cannot search well if we avoid searching at all. Then each search will differ by which search engine & type of medium we are searching—they all have their own quirks, blind spots, and ways to modify a failed search. Often, we will run into walls, each of which has its own circumvention methods. But once we have found something, we are not done: we would often be foolish & short-sighted if we did not then make sure it stayed found. Finally, we might be interested in advanced topics like ensuring in advance resources can be found in the future if need be, or learning about new things we might want to then go find. To illustrate the overall workflow & provide examples of tacit knowledge, I include many Internet case studies of finding hard-to-find things.

Papers

Search

Preparation

Do or do not; there is no try. The first thing you must do is develop a habit of searching when you have a question: “Google is your friend.” Your only search guaranteed to fail is the one you never run. (Beware trivial inconveniences!)

Query Syntax Knowledge

Know your basic Boolean operators & the key G search operators (full list): double quotes for exact matches, hyphens for negation/exclusion, and site: for search a specific website or specific directory of that website (eg. foo site:gwern.net/doc/genetics/, or to exclude folders, foo site:gwern.net -site:gwern.net/doc/). You may also want to play with Advanced Search to understand what is possible. (There are many more G search operators (Russell description) but they aren’t necessarily worth learning, because they implement esoteric functionality and most seem to be buggy1.)

1.

Hotkey Shortcuts (strongly recommended)

Enable some kind of hotkey search with both prompt and copy-paste selection buffer, to turn searching Google (G)/Google Scholar (GS)/Wikipedia (WP) into a reflex.2 You should be able to search instinctively within a split second of becoming curious, with a few keystrokes. (If you can’t use it while IRCing without the other person noting your pauses, it’s not fast enough.)

Example tools: AutoHotkey (Windows), Quicksilver (Mac), xclip+Surfraw/StumpWM’s search-engines/XMonad’s Actions.Search/Prompt.Shell (Linux). DuckDuckGo offers ‘bangs’, within-engine special searches (most are equivalent to a kind of Google site: search), which can be used similarly or combined with prompts/macros/hotkeys.

I make heavy use of the XMonad hotkeys, which I wrote, and which gives me window manager shortcuts: while using any program, I can highlight a title string, and press Super-shift-y to open the current selection as a GS search in a new Firefox tab within an instant; if I want to edit the title (perhaps to add an author surname, year, or keyword), I can instead open a prompt, Super-y, paste with C-y, and edit it before a \n launches the search. As can be imagined, this is extremely helpful for searching for many papers or for searching. (There are in-browser equivalents to these shortcuts but I disfavor them because they only work if you are in the browser, typically require more keystrokes or mouse use, and don’t usually support hotkeys or searching the copy-paste selection buffer: Firefox, Chrome)

1.

Web Browser Hotkeys

For navigating between sets of results and entries, you should have good command of your tabbed web browser. You should be able to go to the address bar, move left/right in tabs, close tabs, open new blank tabs, unclose tabs, go to the nth tab, etc. (In Firefox/Chrome Win/Linux, those are, respectively: C-l, C-PgUp/C-PgDwn, C-w, C-t/C-T, M-[1–9].)

Searching

Having launched your search in, presumably, Google Scholar, you must navigate the GS results. For GS, it is often as simple as clicking on the [PDF] or [HTML] link in the top right which denotes (what GS believes to be) a fulltext link, eg:

![An example of a hit in Google Scholar: note the [HTML] link indicating there is a fulltext Pubmed version of this paper (often overlooked by newbies).](https://gwern.net/doc/technology/google/gwern-googlescholar-search-highlightfulltextlink.png)

An example of a hit in Google Scholar: note the [HTML] link indicating there is a fulltext Pubmed version of this paper (often overlooked by newbies).

GS: if no fulltext in upper right, look for soft walls. In GS, remember that a fulltext link is not always denoted by a “[PDF]” link! Check the top hits by hand: there are often ‘soft walls’ which block web spiders but still let you download fulltext (perhaps after substantial hassle, like SSRN).

Note that GS supports other useful features like alerts for search queries, alerts for anything citing a specific paper, and reverse citation searches (to followup on a paper to look for failures-to-replicate or criticisms of it).

Drilling Down

A useful hit may not turn up immediately. Life is like that.3 You may have to get creative:

Title searches: if a paper fulltext doesn’t turn up on the first page, start tweaking (hard rules cannot be given for this, it requires development of “mechanical sympathy” and asking a mixture of “how would a machine think to classify this” and “how would other people think to write this”):

The Golden Mean: Keep mind when searching, you want some but not too many or too few results. A few hundred hits in GS is around the sweet spot. If you have less than a page of hits, you have made your search too specific.

If nothing is turning up, try trimming the title. Titles tend to have more errors towards the end than the beginning, and people often drop words or phrases at the end—especially subtitles. So start cutting words off the end of the title to broaden the search. Think about what kinds of errors you make when you recall titles: you drop punctuation or subtitles, substitute in more familiar synonyms, or otherwise simplify it. (How might OCR software screw up a title?)

Pay attention to technical terms that pop up in association with your own query terms, particularly in the snippets or full abstracts. Which ones look like they might be more popular than yours, or indicate yours are usually used slightly different from you think they mean? You may need to switch terms.

If deleting a few terms then yields way too many hits, try to filter out large classes of hits with a negation foo -bar, adding as many as necessary; also useful is using OR clauses to open up the search in a more restricted way by adding in possible synonyms, with parentheses for group. This can get quite elaborate, and border on hacking—I have on occasion resorted to search queries as baroque as (foo OR baz) AND (qux OR quux) -bar -garply -waldo -fred to the point where I hit search query length limits and CAPTCHA barriers.4 (By that point, it is time to consider alternate attacks.)

Tweak The Title: quote the title; delete any subtitle; try the subtitle instead; be suspicious of any character which is not alphanumeric and if there are colons, split it into two title quotes (instead of searching Foo bar: baz quux, or "Foo bar: baz quux", search "Foo bar" "baz quux"); swap their order.

Tweak The Metadata:

Add/remove the year.

Add/remove the first author’s surname. Try searching GS for just the author (author:foo).

Delete Odd Characters/Punctuation:

Libgen had trouble with colons for a long time, and many websites still do (eg. GoodReads); I don’t know why colons in particular are such trouble, although hyphens/em-dashes and any kind of quote or apostrophe or period are problematic too. Watch out for words which may be space-separated—if you want to find Arpad Elo’s epochal The Rating of Chessplayers in Libgen, you need to search “The Rating of Chess Players” instead! (This is also an example of why falling back to search by author is a good idea.)

Tweak Spelling: Try alternate spellings of British/American terms. This shouldn’t be necessary, but then, deleting colons or punctuation shouldn’t be necessary either.

Check For Book Publication: many papers are published in the form of book anthologies, not journal articles. So look for the book if the paper is mysteriously absent.

A book will not necessarily turn up in GS and thus its constituent papers may not either; similarly, while SH does a good job of linking article paywalls to their respective book compilation in LG, it is far from infallible. If a paper was published in any kind of ‘proceeding’ or ‘conference’ or ‘series’ or anything with an ISBN, the paper may be absent from the usual places but the book readily available. It can be quite frustrating to be searching hard for a paper and realize the book was there in plain sight all along. (My suggestion in such cases for post-finding is to cut out the relevant page range & upload the paper for others to more easily find.)

Use URLs: if you have a URL, try searching chunks of it, typically towards the end, stripping out dates and domain names.

Date Search:

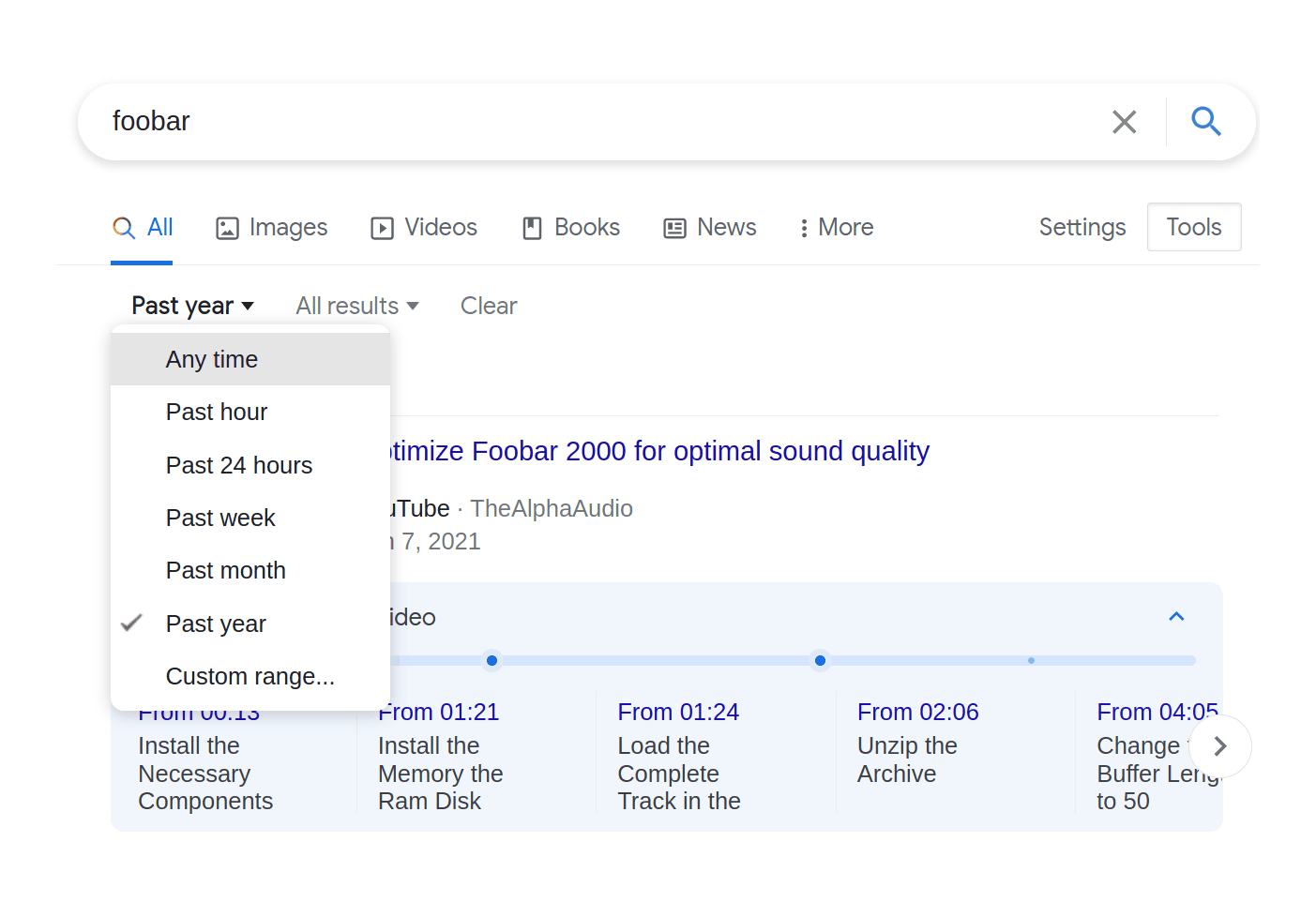

Use a search engine (eg. G/GS) date range feature (in “Tools”) to search ±4 years: metadata can be wrong, publishing conventions can be odd (eg. a magazine published in ‘June’ may actually be published several months before or after), publishers can be extremely slow. This is particularly useful if you add a date constraint & simultaneously loosen the search query to turn up the most temporally-relevant of what would otherwise be far too many hits. If this doesn’t turn up the relevant target, it might turn up related discussions or fixed citations, since most things are cited most shortly after publication and then vanish into obscurity.

Click “Tools” on the far right to access date-range & “verbatim” search modes in Google Search.

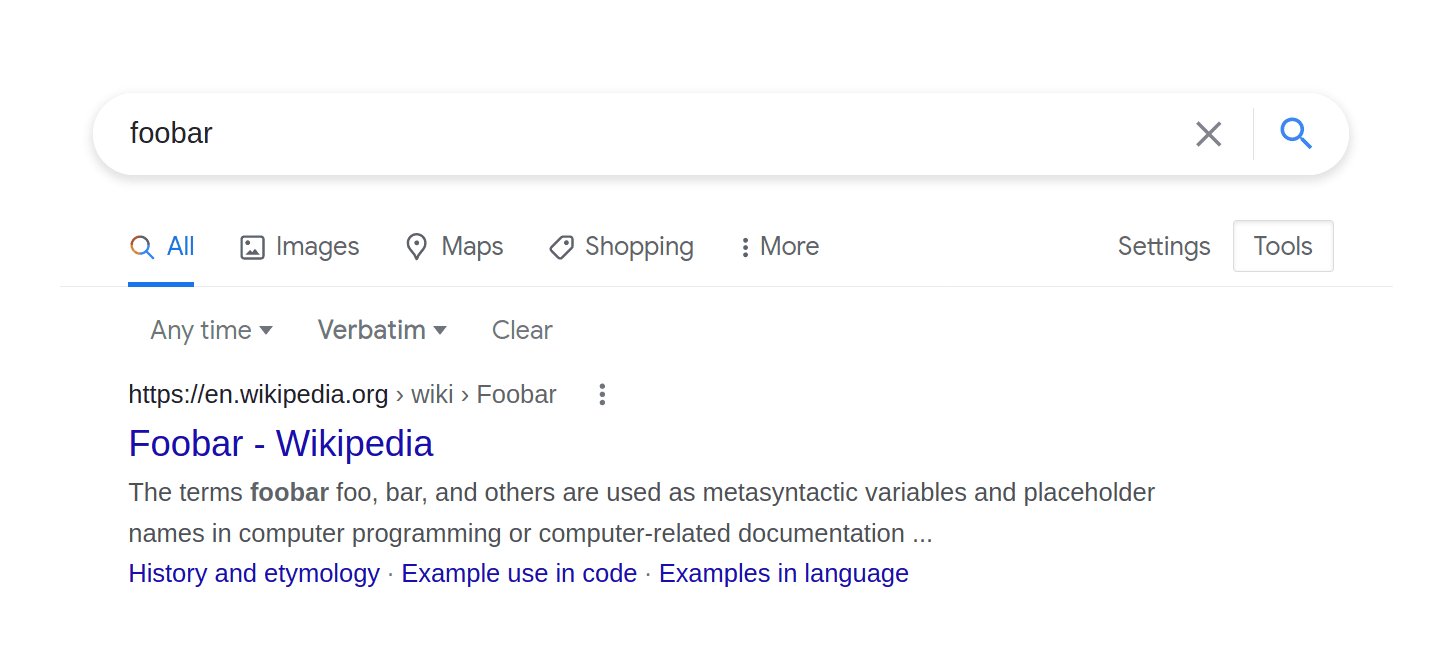

The “verbatim” mode is useful for forcing more literal matching: without it, a search for “foobar” will insist on hits about music players, hiring contests, etc. rather than the programming term itself.

If a year is not specified, try to guess from the medium: popular media has heavy recentist bias & prefers only contemporary research which is ‘news’, while academic publications go back a few more years; the style of the reference can give a hint as to how relatively old some mentioned research or writings is. Frequently, given the author surname and a reasonable guess at some research being a year or two old, the name + date-range + keyword in GS will be enough to find the paper.

Consider errors: typos are common. If nothing is showing up in the date-range despite a specific date, perhaps there was a typographic error. Even a diligent typist will occasionally copy metadata from a previous entry or type the same character twice or 2 characters in the wrong order, and for numbers, there is no spellcheck to help catch such errors. Authors frequently propagate bibliographic errors without correcting them (demonstrating, incidentally, that they probably did not read the original and so any summaries should be taken with a grain of salt). Think about plausible transpositions & neighboring keys on a QWERTY keyboard: eg. a year like “1976” may actually be 196660ya, 196759ya, 197551ya, 197749ya, or 198640ya (but it will not be 1876150ya or 2976 or 198739ya). What typos would you make if you were reading or typing in a hurry? What OCR errors are likely, such as confusing ‘3’/‘8’?

Add Jargon: Add technical terminology which might be used by relevant papers; for example, if you are looking for an article on college admissions statistics, any such analysis would probably be using logistic regression and, even if they do not say “logistic regression” (in favor of some more precise yet unguessable term) would express their effects in terms of “odds”.

If you don’t know what jargon might be used, you may need to back off and look for a review article or textbook or WP page and spend some quality time reading. If you’re using the wrong term, period, nothing will help you; you can spend hours going through countless pages, but that won’t make the wrong term work. You may need to read through overviews until you finally recognize the skeleton of what you want under a completely different (and often rather obtuse) name. Nothing is more frustrating that knowing there must be a large literature on a topic (“Cowen’s Law”) but being unable to find it because it’s named something completely different from expected—and many fields have different names for the same concept or tool. (Occasionally people compile “Rosetta stones” to translate between fields: eg. Baez & Stay2009, Bertsekas2018, Metz et al 2018’s Table 1. These are invaluable.)

Even The Humble Have A Tale: Beware hastily dismissing ‘bibliographic’ websites as useless—they may have more than you think.

While a bibliographic-focused library site like elibrary.ru is (almost) always useless & clutters up search results by hosting only the citation metadata but not fulltext, every so often I run into a peculiar foreign website (often Indian or Chinese) which happens to have a scan of a book or paper. (eg. Darlington1954, which eluded me for well over half an hour until, taking the alternate approach of hunting its volume, I out of desperation clicked on an Indian index/library website which… had it. Go figure.) Sometimes you have to check every hit, just in case.

Search Internet Archive:

The Internet Archive (IA) deserves special mention as a target because it is the Internet’s attic, bursting at the seams with a remarkable assortment of scans & uploads from all sorts of sources—not just archiving web pages, but scanning university collections, accepting uploads from rogue archivists and hackers and obsessive fans and the aforementioned Indian/Chinese libraries with more laissez-faire approaches.5 This extends to its media collections as well—who would expect to find so many old science-fiction magazines (as well as many other magazines), a near-infinite number of Grateful Dead recordings, the original 114 episodes of Tom and Jerry, or thousands of arcade & console & PC & Flash games (all playable in-browser)? The Internet Archive is a veritable Internet in and of itself; the problem, of course, is finding anything…

So not infrequently, a book may be available, or a paper exists in the middle of a scan of an entire journal volume, but the IA will be ranked very low in search queries and the snippet will be misleading due to bad OCR. A good search strategy is to drop the quotes around titles or excerpts and focus down to site:archive.org and check the first few hits by hand. (You can also try the relatively new “Internet Archive Scholar”, which appears to be more comprehensive than Google-site-search.)

Hard Cases

If the basic tricks aren’t giving any hints of working, you will have to get serious. The title may be completely wrong, or it may be indexed under a different author, or not directly indexed at all, or hidden inside a database. Here are some indirect approaches to finding articles:

Reverse Citations: Take a look in GS’s “related articles” or “cited by” to find similar articles such as later versions of a paper which may be useful. (These are also good features to know about if you want to check things like “has this ever been replicated?” or are still figuring out the right jargon to search.)

Anomalous Hits: Look for hints of hidden bibliographic connections and anomalous hits.

Does a paper pop up high in the search results which doesn’t seem to make sense, such as not containing your keywords in the displayed snippet? GS generally penalizes items which exist as simply bibliographic entries, so if one is ranked high in a sea of fulltexts, that should make you wonder why it is being prioritized. Similarly, for Google Books (GB): a book might be forbidden from displaying even snippets but rank high; that might be for a good reason—it may actually contain the fulltext hidden inside it, or something else relevant.

Likewise, you cannot trust metadata too much. The inferred or claimed title may be wrong, and a hit may be your desired target lurking in disguise.

Compilation Files: Some papers can be found by searching for the volume or book title to find it indirectly, especially conference proceedings or anthologies; many papers appear to not be available online but are merely buried deep inside a 500-page PDF, and the G snippet listing is misleading.

Conferences are particularly complex bibliographically, so you may need to apply the same tricks as for page titles: drop parts, don’t fixate on the numbers, know that the authors or ISBN or ordering of “title: subtitle” can differ between sources, etc.

Search By Issue: Another approach is to look up the listing for a journal issue, and find the paper by hand; sometimes papers are listed in the journal issue’s online Table of Contents, but just don’t appear in search engines (‽). In particularly insidious cases, a paper may be digitized & available—but lumped in with another paper due to error, or only as part of a catch-all file which contains the last 20 miscellaneous pages of an issue. Page range citations are particularly helpful here because they show where the overlap is, so you can download the suspicious overlapping ‘papers’ to see what they really contain.

Esoteric as this may sound, this has been a problem on multiple occasions. I searched in vain for any hint of Shepard1929’s existence, half-convinced it was a typo for his 1959 publication, until I turned to the raw journal scans. A particularly epic example was Shockley1966 where after an hour of hunting, all I had was bibliographic echoes despite apparently being published in a high-profile, easily obtained, & definitely digitized journal, Science—leaving me thoroughly baffled. I eventually looked up the ToC and inferred it had been hidden in a set of abstracts!6 (One symptom of the ‘abstract’ or ‘conference presentation’ problem is when the academic databases keep claiming to have fulltext of a paper, but then mysteriously error out when you try to actually access it. Apparently they can be inconsistent internally and know that they have it in the full journal scans, but not know where just that one abstract ‘is’.) Or a number of SMPY papers turned out to be split or merged with neighboring items in journal issues, and I had to fix them by hand.

Masters/PhD Theses: sorry. It may be hopeless if it’s pre-2000. You may well find the citation and even an abstract, but actual fulltext…?

If you have a university proxy, you may be able to get a copy off ProQuest (specializing in US theses). If ProQuest does not allow a download but indexes it, that usually means it has a copy archived on microfilm/microfiche, but no one has yet paid for a scan to be made; you can sign up without any special permission, and then purchase ProQuest scans for ~$43 (as of 2023), and that gives you a downloadable PDF. (They apparently scan non-digital works from their vast backlog only on request, so it’s almost like ransoming papers; which means that buying a scan makes it available to academic subscribers as part of the ProQuest database.)

Otherwise, you need full university ILL services7, and even that might not be enough (a surprising number of universities appear to restrict access only to the university students/faculty, with the complicating factor of most theses being stored on microfilm).

Reverse Image Search: If images are involved, a reverse image search in Google Images or TinEye or Yandex Search can turn up important leads.

Bellingcat has a good guide by Aric Toller: “Guide To Using Reverse Image Search For Investigations”. (Yandex image search appears to exploit face recognition, text OCR, and other capabilities Google Images will not, and bows less to copyright concerns.)

Use Browser Page Info to Bypass Image Restrictions

If you are having trouble downloading an image from a web page which is badly/maliciously designed to stop you, use “View Page Info”’s (C-I) “Media” tab (eg), which will list the images in a page and let one download them directly.

Enemy Action: Is a page or topic not turning up in Google/IA that you know ought to be there? Check the website’s robots.txt & sitemap. While not as relevant as they used to be (due to increasing use of dynamic pages & entities ignoring it), robots.txt can sometimes be relevant: key URLs may be excluded from search results, and overly-restrictive robots.txt can cause enormous holes in IA coverage, which may be impossible to fix (but at least you’ll know why).

Patience: not every paywall can be bypassed immediately, and papers may be embargoed or proxies not immediately available.

If something is not available at the moment, it may become available in a few months. Use calendar reminders to check back in to see if an embargoed paper is available or if LG/SH have obtained it, and whether to proceed to additional search steps like manual requests.

Domain Knowledge-Specific Tips:

Twitter: Twitter is indexed in Google so web searches may turn up hits, but if you know any metadata, Twitter’s native search functions are still relatively powerful (although Twitter limits searches in many ways in order to drive business to its staggeringly-expensive ‘firehose’ & historical analytics). Use of Twitter’s “advanced search” interface, particularly the from: & to: search query operators, can vastly cut down the search space. (Also of note: list:, -filter:retweets, near:, url:, & since:/until:.)

US federal courts: US federal court documents can be downloaded off PACER after registration.

PACER is pay-per-page ($0.14$0.12018/page) but users under a certain level each quarter (currently $20.38$152018) have their fees waived, so if you are careful, you may not need to pay anything at all. There is a public mirror on Courtlistener, called RECAP, which can be freely searched & downloaded.

If you fail to find a case in RECAP and must use PACER (as often happens for obscure cases), please install the Firefox/Chrome RECAP browser extension, which will copy anything you download into RECAP. (This can be handy if you realize later that you should’ve kept a long PDF you downloaded or want to double-check a docket.)

Navigating PACER can be difficult because it is an old & highly specialized computer system which assumes you are a lawyer, or at least very familiar with PACER & the American federal court system. As a rule of thumb, if you are looking up a particular case, what you want to do is to search for the first name & surname (even if you have the case ID) for either criminal or civil cases as relevant, and pull up all cases which might pertain to an individual; there can be multiple cases, cases can hibernate for years, be closed, reopened as a different case number, etc. Once you have found the most active or relevant case, you want to look at the “docket”, and check the options to see all documents in the case. This will pull up a list of many documents as the case unfolds over time; most of these documents are legal bureaucracy, like rescheduling hearings or notifications of changed lawyers. You want the longest documents, as those are most likely to be useful. In particular, you want the “indictment”, the “criminal complaint”8, and any transcripts of trial testimony.9 Shorter documents, like 1–2pg entries in the docket, can be useful, but are much less likely to be useful unless you are interested in the exact details of how things like pre-trial negotiations unfold. So carelessly choosing the ‘download all’ option on PACER may blow through your quarterly budget without getting you anything interesting (and also may interfere with RECAP uploading documents).

There is no equivalent for state or county court systems, which are balkanized and use a thousand different systems (often privatized & charging far more than PACER); those must be handled on a case by case basis. (Interesting trivia point: according to Nick Bilton’s account of the Silk Road 1 case, the FBI and other federal agencies in the SR1 investigation would deliberately steer cases into state rather than federal courts in order to hide them from the relative transparency of the PACER system. The use of multiple court systems can backfire on them, however, as in the case of SR2’s DoctorClu (see the DNM arrest census for details), where the local police filings revealed the use of hacking techniques to deanonymize SR2 Tor users, implicating CMU’s CERT center—details which were belatedly scrubbed from the PACER filings.)

charity financials: for USA charity financial filings, do Form 990 site:charity.com and then check GuideStar (eg. looking at Girl Scouts filings or “Case Study: Reading Edge’s financial filings”). For UK charities, the Charity Commission for England and Wales may be helpful.

education research: for anything related to education, do a site search of ERIC, which is similar to IA in that it will often have fulltext which is buried in the usual search results

Wellcome Library: the Wellcome Library has many old journals or books digitized which are impossible to find elsewhere; unfortunately, their SEO is awful & their PDFs are unnecessarily hidden behind click-through EULAs, so they will not show up normally in Google Scholar or elsewhere. If you see the Wellcome Library in your Google hits, check it out carefully.

magazines (as opposed to scholarly or trade journals) are hard to get.

They are not covered in Libgen/Sci-Hub, which outsource that to MagzDB; coverage is poor, however. An alternative is pdf-giant. Particularly for pre-2000 magazines, one may have to resort to looking for old used copies on eBay. Some magazines are easier than others—I generally give up if I run into a New Scientist citation because it’s never worth the trouble.

Newspapers: like theses, tricky. I don’t know of any general solutions short of a LexisNexis subscription.10 An interesting resource for American papers is Chronicling America’s “Historic American Newspaper” scans.

By Quote or Description

For quote/description searches: if you don’t have a title and are falling back on searching quotes, try varying your search similarly to titles:

Novel sentences: Try the easy search first—whatever looks most memorable or unique.

Short quotes are unique: Don’t search too long a quote, a sentence or two is usually enough to be near-unique, and can be helpful in turning up other sources quoting different chunks which may have better citations.

Break up quotes: Because even phrases can be unique, try multiple sub-quotes from a big quote, especially from the beginning and end, which are likely to overlap with quotes which have prior or subsequent passages. This can be critical with apocryphal quotes, which often delete less witty sub-passages while accreting new material. (An extreme example would be the Oliver Heaviside quote.)

Odd idiosyncratic wording: Search for oddly-specific phrases or words, especially numbers. 3 or 4 keywords is usually enough.

Paraphrasing: Look for passages in the original text which seem like they might be based on the same source, particularly if they are simply dropped in without any hint at sourcing and don’t sound like the author; authors typically don’t cite every time they draw on a source, usually only the first time, and during editing the ‘first’ appearance of a source could easily have been moved to later in the text. All of these additional uses are something to add to your searches.

Robust Quotes: You are fighting a game of Chinese whispers, so look for unique-sounding sentences and terms which can survive garbling in the repeated transmissions.

Memories are urban legends told by one neuron to another over the years. Pay attention to how you mis-remember things: you distort them by simplifying them, rounding them to the nearest easiest version, and by adding in details which should have been there. Avoid phrases which could be easily reworded in multiple equivalent ways, as people usually will reword them when quoting from memory, screwing up literal searches. Remember the fallibility of memory and the basic principles of textual criticism: people substitute easy-to-remember versions for the hard, long11, or unusual original.

Tweak Spelling: Watch out for punctuation and spelling differences hiding hits.

Gradient Ascent: Longer, less witty versions are usually closer to the original and a sign you are on the right trail. The worse, the better. Sniff in the direction of worse versions. (Authors all too often fail to write what they were supposed to write—as Yogi Berra remarked, “I really didn’t say everything I said.”)

Search Books: Switch to GB and hope someone paraphrases or quotes it, and includes a real citation; if you can’t see the full passage or the reference section, look up the book in Libgen.

Dealing With Paywalls

Gold once out of the earth is no more due unto it; What was unreasonably committed to the ground is reasonably resumed from it: Let Monuments and rich Fabricks, not Riches adorn mens ashes. The commerce of the living is not to be transferred unto the dead: It is not injustice to take that which none complains to lose, and no man is wronged where no man is possessor.

Use Sci-Hub/Libgen for books/papers. A paywall can usually be bypassed by using Libgen (LG)/Sci-Hub (SH): papers can be searched directly (ideally with the DOI12, but title+author with no quotes will usually work), or an easier way may be to prepend13 sci-hub.st (or whatever SH mirror you prefer) to the URL of a paywall. Occasionally Sci-Hub will not have a paper or will persistently error out with some HTTP or proxy error, but searching the DOI in Libgen directly will work. Finally, there is a LibGen/Sci-Hub fulltext search engine on the Z-Library mirror, which is a useful alternative to Google Books (despite the poor OCR).

Use university Internet. If those don’t work and you do not have a university proxy or alumni access, many university libraries have IP-based access rules and also open WiFi or Internet-capable computers with public logins inside the library, which can be used, if you are willing to take the time to visit a university in person, for using their databases (probably a good idea to keep a list of needed items before paying a visit).

Public libraries too. Public libraries often subscribe to commercial newspapers or magazine databases; they are inconvenient to get to, but you can usually at least check what’s available on their website. Public & school libraries also have a useful trick for getting common schooling-related resources, such as the OED, or the archives of the New York Times or New Yorker: because of their usually unsophisticated & transient userbase, some public & school libraries will post lists of usernames/passwords on their website (sometimes as a PDF). They shouldn’t, but they do. Googling phrases like “public library New Yorker username password” can turn up examples of these. Used discreetly to fetch an article or two, it will do them no harm. (This trick works less well with passwords to anything else.)

If that doesn’t work, there is a more opaque ecosystem of filesharing services: booksc/bookfi/bookzz, private torrent trackers like Bibliotik, IRC channels with XDCC bots like #bookz/#ebooks, old P2P networks like eMule, private DC++ hubs…

Site-specific notes:

PubMed: most papers with a PMC ID can be purchased through the Chinese scanning service Eureka Mag; scans are $39.02$302020 & electronic papers are $26.01$202020.

Elsevier/sciencedirect.com: easy, always available via SH/LG

Note that many Elsevier journal websites do not work with the SH proxy, although their sciencedirect.com version does and/or the paper is already in LG. If you see a link to sciencedirect.com on a paywall, try it if SH fails on the journal website itself.

PsycNET: one of the worst sites; SH/LG never work with the URL method, rarely work with paper titles/DOIs, and with my university library proxy, loaded pages ‘expire’ and redirect while breaking the browser back button (‽‽‽), combined searches don’t usually work (frequently failing to pull up even bibliographic entries), and only DOI or manual title searches in the EBSCOhost database have a chance of fulltext. (EBSCOhost itself is a fragile search engine which is difficult to query reliably in the absence of a DOI.)

Try to find the paper anywhere else besides PsycNET!

ProQuest/JSTOR: ProQuest/JSTOR are not standard academic publishers, but have access to or mirrors of a surprisingly large number of publications.

I have been surprised how often I have hit dead-ends, and then discovered a copy sitting in ProQuest/JSTOR, poorly-indexed by search engines.

Custom journal websites: sometimes a journal will have its own website (eg. Cell or Florida Tax Review), but will still be ultimately run by one of the giants like Elsevier or HeinOnline. (You can often see hints of this in the site design, such as the footer, the URL structure, direct links to the publisher version, etc.)

When this is the case, it is usually a waste of time to try to use the journal website: it won’t whitelist university IPs, SH/LG won’t know how to handle it, etc. Instead, look for the alternative version.

Request

Human flesh search engine. Last resort: if none of this works, there are a few places online you can request a copy (however, they will usually fail if you have exhausted all previous avenues):

/r/scholar

#icanhazpdf

Wikipedia Resource Request

Finally, you can always try to contact the author. This only occasionally works for the papers I have the hardest time with, since they tend to be old ones where the author is dead or unreachable—any author publishing a paper since 199036ya will usually have been digitized somewhere—but it’s easy to try.

Post-Finding

After finding a fulltext copy, you should find a reliable long-term link/place to store it and make it more findable (remember—if it’s not in Google/Google Scholar, it doesn’t exist!):

Never Link Unreliable Hosts:

LG/SH: Always operate under the assumption they could be gone tomorrow. (As my uncle found out with Library.nu shortly after paying for a lifetime membership!) There are no guarantees either one will be around for long under their legal assaults or the behind-the-scenes dramas, and no guarantee that they are being properly mirrored or will be restored elsewhere.

When in doubt, make a copy. Disk space is cheaper every day. Download anything you need and keep a copy of it yourself and, ideally, host it publicly.

NBER: never rely on a papers.nber.org/tmp/ or psycnet.apa.org URL, as they are temporary. (SSRN is also undesirable due to making it increasingly difficult to download, but it is at least reliable.)

Scribd: never link Scribd—they are a scummy website which impede downloads, and anything on Scribd usually first appeared elsewhere anyway. (In fact, if you run into anything vaguely useful-looking which exists only on Scribd, you’ll do humanity a service if you copy it elsewhere just in case.)

RG: avoid linking to ResearchGate (compromised by new ownership & PDFs get deleted routinely, apparently often by authors) or Academia.edu (the URLs are one-time and break)

high-impact journals: be careful linking to Nature.com or Cell (if a paper is not explicitly marked as Open Access, even if it’s available, it may disappear in a few months!14); similarly, watch out for wiley.com, tandfonline.com, jstor.org, springer.com, springerlink.com, & mendeley.com, who pull similar shenanigans.

~/: be careful linking to academic personal directories on university websites (often noticeable by the Unix convention .edu/~user/ or by directories suggestive of ephemeral hosting, like .edu/cs/course112/readings/foo.pdf); they have short half-lives.

?token=: beware any PDF URL with a lot of trailing garbage in the URL such as query strings like ?casa_token or ?cookie or ?X (or hosted on S3/AWS); such links may or may not work for other people but will surely stop working soon. (Academia.edu, Nature, and Elsevier are particularly egregious offenders here.)

PDF Editing: if a scan, it may be worth editing the PDF to crop the edges, threshold to binarize it (which, for a bad grayscale or color scan, can drastically reduce filesize while increasing readability), and OCR it.

I use gscan2pdf but there are alternatives worth checking out.