Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was running for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination when he sat for an interview with Jordan B. Peterson, a controversial Canadian psychologist, during his eponymous podcast. About an hour into the conversation, which published in June 2023, Kennedy pivoted from answering a question about climate change to bringing up a very different subject: He stated that a lot of the sexual dysphoria seen in children, particularly in boys, “is coming from chemical exposures.”

At the time, Kennedy — now the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services — singled out atrazine, a common herbicide that’s a frequent contaminant in U.S. drinking water supplies. Atrazine will “chemically castrate and forcibly feminize…

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was running for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination when he sat for an interview with Jordan B. Peterson, a controversial Canadian psychologist, during his eponymous podcast. About an hour into the conversation, which published in June 2023, Kennedy pivoted from answering a question about climate change to bringing up a very different subject: He stated that a lot of the sexual dysphoria seen in children, particularly in boys, “is coming from chemical exposures.”

At the time, Kennedy — now the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services — singled out atrazine, a common herbicide that’s a frequent contaminant in U.S. drinking water supplies. Atrazine will “chemically castrate and forcibly feminize” exposed frogs in a tank, he said, adding that “if it’s doing that to frogs, there’s a lot of other evidence that it’s doing it to human beings as well.”

During his presidential run in 2023, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. spoke with Jordan B. Peterson in a hour-plus podcast episode. Of the many topics covered, Kennedy pointed to “chemical exposures” as a cause of sexual dysphoria in children, particularly in boys.

Kennedy, whose criticism of vaccines and chemical additives in processed foods is well known, was referring to research by Tyrone Hayes, a developmental endocrinologist at the University of California, Berkeley who studies the hormonal effects of chemical pollutants on amphibians. In 2010, Hayes and his co-authors reported lab findings showing that 10 percent of genetically male frogs reared in atrazine-spiked water — four out of the 40 grown to adulthood — had developed female reproductive organs. The frogs were exposed at a level equal to about a drop of atrazine in 5,000 gallons of water, a minuscule amount. Yet two of the animals had grown ovaries and could produce eggs, a finding that Kennedy noted during Peterson’s podcast.

Other right-wing media personalities have echoed similar themes about how environmental chemicals might affect a person’s gender and sexuality. Alex Jones, the shock-jock radio host and conspiracy theorist, shouted on his show InfoWars that “I don’t like them putting chemicals in the water that turn the freakin’ frogs gay” — comments that were then remixed into a video that went viral. When asked during a speech at UC Berkeley about biological and chemical changes that may be affecting how people see gender, the podcaster and right-wing political commentator Matt Walsh referenced what he called “a proliferation of transgenderism” and said there’s “something in our diet and our environment that’s affecting us at a really basic internal level.”

These sorts of speculations are often driven by political and cultural interests — and, in some cases, personal biases. They also tend to oversimplify the wildly complicated processes involved in human development and reproduction.

“No study has directly examined the association between prenatal environmental exposures and a clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria.”

Atrazine is among many endocrine-disrupting chemicals, or EDCs, polluting the planet today. These chemicals do appear to interfere with hormones that control early embryonic development, and studies have linked them with cancer, reproductive disorders, and other maladies in wildlife. Both high and low dose exposures have also been linked to adverse effects in humans.

Some investigators who study EDCs have speculated that early exposure to these agents might play some role in human gender dysphoria, too. Steven Holladay, a professor at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, for example, published a review of evidence in 2023 that, he wrote, may “support an environmental chemical contribution to some transgender identities.” That EDCs might affect human brains in ways that cause people to reject a gender that conforms with their assigned sex at birth is a possibility that “should not be dismissed,” he wrote. (Holladay declined to be interviewed, stating via email that many years ago, a publication had represented his “message poorly to sell more papers.”)

As part of a multicenter study in Sweden, researchers are looking into whether early exposures to EDCs correlate later in life with a clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria — meaning the distress and discomfort people feel if their perception of their own gender and their sex assigned at birth don’t align. The Swedish Gender Dysphoria study launched in 2016 — primarily to better understand the psychosocial and mental health outcomes of gender dysphoria, but also its underlying causes. The focus on early EDC exposure is motivated in part by curiosity among scientists, clinicians, and others over the “marked increase in the number of people seeking healthcare for gender dysphoria over the past 10-12 years,” wrote Fotis Papadopoulos, the study’s lead investigator and a psychiatrist at Uppsala University Hospital’s Gender Identity Clinic, in response to emailed questions.

Papadopoulos pointed out that, to his knowledge, “no study has directly examined the association between prenatal environmental exposures and a clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria.” Indeed, there’s still no conclusive link between EDC exposures and human transgender identity, and moreover, attempts to explore such an association are wildly contentious — not just because they are so speculative, but also because they’re based on “the assumption that something ‘went wrong’ in the brains of trans and nonbinary people,” said Troy Roepke, a neuroendocrinologist at Rutgers University, who is genderqueer, a term that describes people whose gender identity doesn’t conform with conventional binary distinctions. (Roepke, who uses they/them pronouns, emphasized that they were speaking as an expert in their field and not on behalf of the university.)

Get Our Newsletter

Sent Weekly

The question plays into fraught debates over the origins of gender identity itself. It also feeds a notion that there could be “a prevention or treatment or cure strategy to eliminate us from existence,” Roepke said, adding that this line of inquiry feels dangerous, “especially in light of the current climate and animosity towards LGBTQIA-plus people like myself.” Transgender researchers and others have expressed a concern, for example, that research exploring the neurobiology of gender dysphoria might be used to rationalize corrective or conversion therapies that aim to suppress transgender identity.

Conscious of such concerns, several researchers who did speak to Undark were emphatic that chemical influences on gender identity, should they exist at all, shouldn’t be construed as harmful in the way that reproductive toxicities are. “We have to be very careful not to frame gender non-conforming as an adverse effect,” said Shanna Swan, an environmental and reproductive epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. In recent years, her work has focused on how EDC exposures, particularly during prenatal development, can affect sperm counts, fertility, and other developmental outcomes. Her research in animals and humans suggests that exposure to EDCs in the womb can blur physiological and behavioral sex differences in offspring. Still, Swan emphasized that these studies provide limited insights into gender identity in people. “How do you decide that somebody’s gender dysphoric?” she asked. “You ask them, right? It’s not something you can measure physiologically.”

Developmental endocrinologist Tyrone Hayes studies the hormonal effects of chemical pollutants on amphibians. His work on the endocrine-disrupting chemical atrazine has led him to believe it should be banned, but not that EDCs are associated with transgender identity.

Visual: Courtesy of Tyrone Hayes

When asked to comment on Kennedy’s statements about atrazine and EDCs, Hayes, the Berkeley endocrinologist, argued that there are plenty of environmental reasons outside of any purported impacts on human gender identity to phase out the chemical. He and Kennedy “agree on one thing,” said Hayes, “and that is that atrazine should be banned.”

Hayes added that while it’s theoretically possible that EDCs are associated in some way with transgender identity, “there’s no evidence to support that in humans.” And like other experts interviewed for this story, Hayes also questioned whether populations of transgender people were truly on the rise, which one would expect if Kennedy’s theory of gender identity and EDCs were a contributing factor. As it stands, EDCs have been released into the global environment for decades.

To be sure, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds who self-identify as transgender in the United States nearly quintupled between 2014 and 2022, increasing from 0.59 percent to 2.78 percent, according to a national survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The largest increase was among White transgender men. But while Kennedy and Jones see a chemical culprit, and still others suggest social influences may play a role, Hayes and Roepke remain skeptical that these increases reflect anything more than a cultural moment wherein transgender people feel more comfortable revealing or exploring their gender identity.

“I don’t think there’s a way we would say that there’s more of us now than there were then,” said Roepke. “We’re just more open about it.”

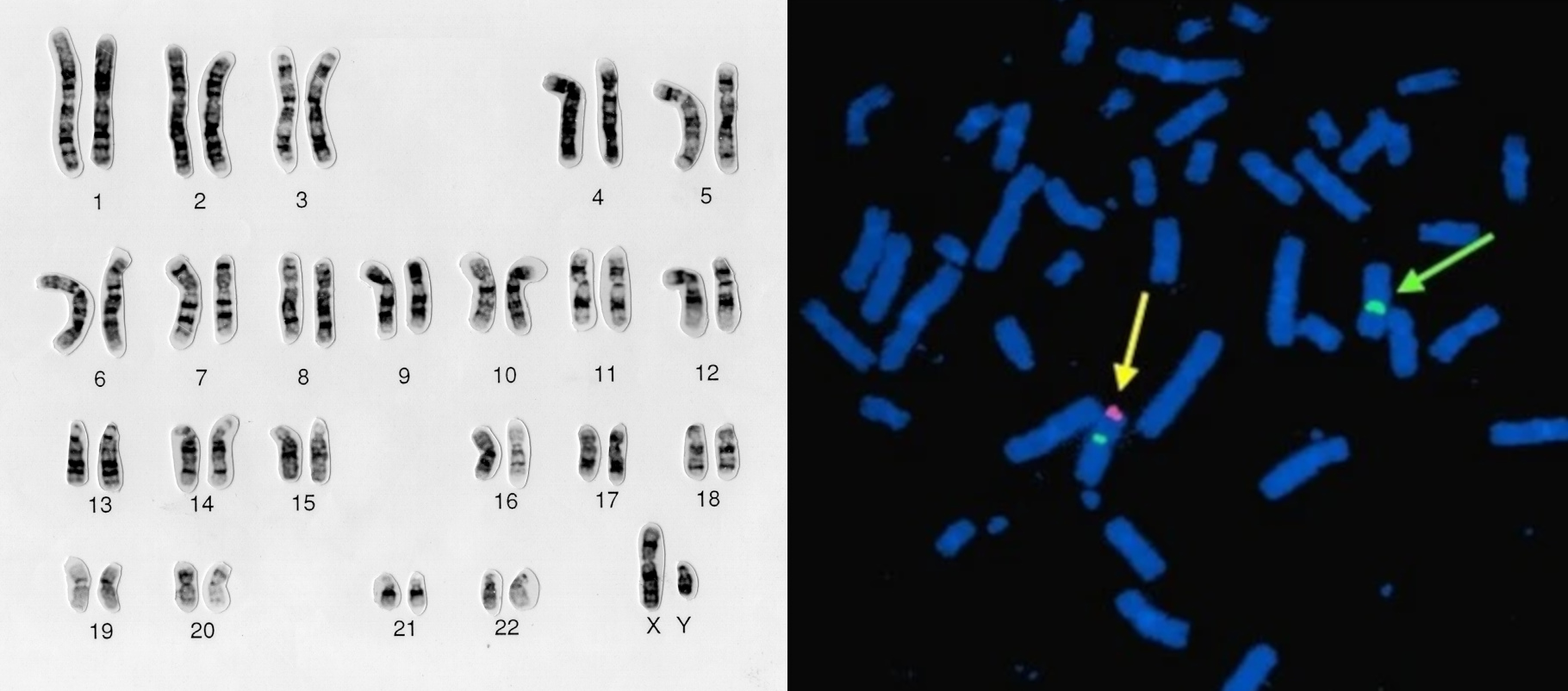

In theory, EDCs may interfere with the earliest stages of sexual development. While genetic sex, based on an individual’s chromosomes, is determined at fertilization, a newly formed human embryo contains structures that are able to develop into male or female genitalia.

The sex-determining pendulum may swing one way or another depending on a gene called SRY. This gene is ordinarily located on the Y chromosome — most human embryos either have a pair of X chromosomes, which typically develop as female, or an X and a Y chromosome, which usually develop as male — and it is activated six weeks after ovulation in a human pregnancy, sparking a cascade of events that ultimately develop key features of the male reproductive system, including the testes. If there’s no SRY gene — which is typical for someone with two X chromosomes — then a different cascade occurs, and the embryo develops the female reproductive system, including ovaries.

The sex-determining process doesn’t always happen so neatly, however: The SRY gene can show up on the X chromosome, for instance, resulting in a genetic female with testes. If the SRY gene doesn’t work in the usual way, then a genetic male might develop a uterus and fallopian tubes. Some genetic males don’t have the working receptors needed to respond to male sex hormones called androgens — of which testosterone is the most common — or have only a partial ability to respond, which means that they can develop typically female or sexually ambiguous genitalia. (People whose anatomies are not typically male or female may be intersex, which is distinct from being transgender.)

Left: Typical male chromosomes, with one X and one Y chromosome. Right: The chromosomes of a man with two X chromosomes. In this study, the SRY gene was tagged and imaged so that it would appear under a microscope as an orange or pink color. A yellow arrow points to its location at the end of an X chromosome. Visual: Left: Wessex Reg. Genetics Center/Wellcome Collection; Right: L. Rawal et al, Journal of Rare Diseases, 2024.

Hormones also coordinate sexual differentiation in the brain. Male brains develop in response to a surge in levels of testosterone during the second trimester of pregnancy, while female brains develop in the absence of the hormone. Still, scientists debate to what extent male and female brains differ, and exactly which areas of the brain are affected. Evidence points to tremendous overlap, but also to some distinct features in many species. Male brains on average have larger volumes, for instance, and some research suggests that they are wired more for spatial abilities, while female brains are preferentially wired for navigating social interactions. And in humans, there’s evidence suggesting that “females have better language abilities,” Swan said. Such research examines the physiological features that might influence sex-specific behavioral differences but doesn’t capture the social factors, which have a large body of research of their own.

The reproductive system and the brain generally develop in coordination, but if something interferes with the hormones that drive these events, then the result could be “people who identify with a gender different from their physical sex,” wrote Charles Roselli, a now-retired professor from Oregon Health & Science University, in a 2018 review paper on the neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation. (Roselli, whose research specialized in how sex hormones affect the brain, turned down an interview for this article via a press officer, who said in an email that Roselli “clarified that to his awareness there is no animal model for gender identity.”)

Shanna Swan, an environmental and reproductive epidemiologist. In recent years, her work has focused on how EDC exposures, particularly during prenatal development, can affect sperm counts, fertility, and other developmental outcomes.

Visual: Courtesy of Shanna Swan

Could EDCs provide this sort of interference? It’s possible, but not proven, that differences in the brains between sexes could be lessened “under the influence of toxics,” Swan said.

Some EDCs, for instance, may affect mating behavior in rodents and other species. Female rats ordinarily arch their backs in response to mounting by males, but a 2024 review found that in some studies, they did so less frequently if exposed to certain EDCs in the womb. (The results for Bisphenol A, an estrogen-mimicking plastics additive, were mixed, with some studies finding no change or even an increase in such behavior.) In male rodents, the review found, EDC exposure may affect mating frequency and timing.

Other sex-specific changes have also been reported. A team in Denmark exposed pregnant rats to low doses of BPA and found that the female offspring showed improved performance on tests of spatial learning, a finding the authors described as “masculinization of the brain.”

But finding associations in rodent studies is a ways off from being able to draw conclusions about how EDCs might affect sex-specific brain differences in humans.

In lab experiments, researchers can expose animals to EDCs and observe the effects, whereas human studies are limited to evaluating effects from real-world exposures to the chemicals. Swan and her colleagues in Sweden and the United States reported in 2018 that in-utero EDC exposures compromise language skills in preschool-aged children. The scientists measured traces of EDCs called phthalates in mothers’ urine and found that increasing levels predicted a worsening ability among boys to understand 50 words or more, based on questionnaires filled out by their mothers. The results for girls were inconclusive.

It’s possible, but not proven, that differences in the brains between sexes could be lessened “under the influence of toxics.”

Humans and many other mammals also show sex-specific differences in play behavior from an early age. Research suggests that among many species of rodents and non-human primates, for example, males tend to engage in more play fighting than females, although that’s not the case across all animals.. This type of play tends to be more common in human boys as well.

After controlling for social factors, including parental attitudes towards what Swan described as atypical play choices, she found in a study published in 2010 that EDCs affected play behavior in boys, who showed less interest in ball sports and toys like guns, swords, and tool sets. Swan said the results of her study suggest that the EDC-exposed boys were “less male-typical because they’re less likely to engage in these male-typical play behaviors.” But she insisted her findings can’t speak to other sex-linked behaviors or to the boys’ experience of gender. “It just, at this point in their life they are playing more like girls and boys.”

In what may be the only effort to have published research investigating EDCs’ effects on human gender identity specifically, a French-led team studied a cohort of 253 adults who were assigned male at birth and were born to mothers who had been treated with diethylstilbestrol, or DES, a synthetic estrogen, during pregnancy. DES — which indirectly reduces testosterone production in the body — was used to prevent miscarriage and other pregnancy complications decades ago, but its uses fell off after research linked it with a higher risk of a type of vaginal cancer among women who were exposed to the drug in-utero.

The French-led team noted in 2024 that four people from the DES-exposed cohort — or 1.58 percent of the cohort overall — reported having female identities since childhood and adolescence. The researchers wrote that the finding “strongly suggests that DES plays a role in male to female transgender development,” adding that the rate uncovered in the study was much higher “than in the general population.” In reality, the rate is not far off from other reported size estimates of the adult transgender population, which vary according to where and how the data are collected and whether researchers broaden criteria to include other descriptors, such as gender ambivalence.

Moving toward proof that EDCs and transgender identities are actually related might require a deeper, longitudinal study, said an expert who did not want to be identified due to the sensitivity of the research question and the lack of data available. Researchers could measure the mothers’ exposures to EDCs during pregnancy, follow the children over time, and then get them to “honestly talk” about their own gender identity, which is inevitably going to be a limiting factor in providing that kind of causality in humans, the researcher said.

Studies that aim to explore any potential biological underpinnings of gender identity can face considerable hurdles, however, in part because of the “fear, I would say, of this kind of research,” said Ivanka Savic, a neurologist and neuroscientist at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute. Savic has spent years doing brain imaging studies in transgender people that, in her words, point to decreased connection between brain circuits that mediate “perception of our one’s body and the perception of self.” She’s also an adjunct professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she previously worked with collaborators on investigations partly funded by the National Institutes of Health into the neurobiology of gender dysphoria.

A 2017 published by Ivanka Savic, a neurologist and neuroscientist at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, and co-authors. Savic has spent years doing such brain imaging studies in transgender people.

Visual: S. M. Burke et al, Scientific Reports, 2017.

In 2020, her team was working on a study on transgender identity that the lead researcher paused the following year after transgender researchers and other academics wrote to members of the university and trans advocacy groups warned their local constituencies against participating. According to Phil Hampton, senior director of communications at UCLA Health, following a review, changes were made to the design and execution of the study. It closed in 2023.

An earlier study of the origins of transgender identity planned by a consortium of five research institutions in the United States and Europe similarly faced challenges. According to a 2017 news article by Reuters, the investigators had collected extracted DNA from blood samples from 10,000 people, both trans- and cisgender, and were ramping up to screen them for genomic markers. But “we decided that we needed to pivot and do more community engagement on the topic before launching into the science,” Lea Davis, leader of the study and a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, told Undark via email when asked if the study had been published. Davis declined a later request for an interview, citing her concerns over the “potential for misuse of science to further harm the nonbinary and trans community.”

Savic said her studies of brain differences between trans- and cisgender people are motivated not by politics but rather “pure science” and her position as a medical professional. Her aim, she explained, is merely to discover more about how the brain perceives the body’s physical appearance, and whether these insights shed any light on why someone might view their gender identity as being different from their biological sex. Papadopoulos, the lead of the Swedish Gender Dysphoria study, acknowledged the risk of research into the biology of gender identity and wrote that “this is why we need to report in a scientific sound and ethically correct way.”

But to some in the trans community, these kinds of studies pose an existential threat. Those who called out the study Savic was working on at UCLA expressed worry that the findings might be applied to medical gatekeeping, or the potential denial of gender-affirming care to people who don’t meet clinically defined thresholds. Grounding discussions of transgender identity “solely in the terrain of neuroscience and biology,” they wrote, “undercuts this critical point: we are who we say we are, regardless of biological evidence.”

What the science does show “is that when you make it more possible for people to be who they are without being arrested or killed, then you see more of them.”

Kellan Baker, senior adviser for health policy at the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit think tank, was adamant that there’s no evidence to demonstrate any kind of link between environmental contaminants and gender dysphoria. What the science does show “is that when you make it more possible for people to be who they are without being arrested or killed, then you see more of them,” said Baker, who is transgender. “No one is proposing to look for the etiology of being cisgender, which reinforces for me — and I imagine for many transgender people — that many such studies are looking at being transgender as a ‘problem’ to be ‘fixed,’” he added in an email.

Given the controversial nature of the topic, researchers interviewed for this story insisted on the importance of maintaining cultural sensitivity. People who have a gender identity that differs from their sex at birth are making “what they feel is the appropriate choice” that aligns with “how they feel about themselves,” Swan said.

“So in that sense,” she added, “if chemicals were involved in some way, those chemicals would be a positive, not a negative.”

Meanwhile, back at UC Berkeley, Hayes is still busy studying the environmental cues that change hormones and sex differentiation. Asked if scientists should investigate potential associations between EDCs and transgender identity, he responded “yes, absolutely.” But Hayes also cautioned against using the research in ways that could demonize or lead to the discrimination of certain groups of people.

To say we shouldn’t do the science “would be like me saying we shouldn’t do genetics because of this thing called eugenics,” he said. “I think the science should be done, but with an appreciation and understanding of how it can be manipulated in political ways.”