As a child, Sruli Recht spent more time in his mind than in his body. Diagnosed early with cystic fibrosis, he found himself falling into his imagination—nurturing what would later become a hypervigilant mind constantly scuttling across the world around him in search of meaning, behaviors, and patterns.

“As someone who has always been an outsider in every place they’ve been, I have to very quickly map the behavior of the room. The environment. The cultures and behaviors—either fit in, which is not easy to do, or blend within that,” he tells me over the phone from China, where he’s working on a new show, Lair. “And within that hypervigilance, where I’m always assessing everything, I might see a behavior or something that sticks out. Then that might …

As a child, Sruli Recht spent more time in his mind than in his body. Diagnosed early with cystic fibrosis, he found himself falling into his imagination—nurturing what would later become a hypervigilant mind constantly scuttling across the world around him in search of meaning, behaviors, and patterns.

“As someone who has always been an outsider in every place they’ve been, I have to very quickly map the behavior of the room. The environment. The cultures and behaviors—either fit in, which is not easy to do, or blend within that,” he tells me over the phone from China, where he’s working on a new show, Lair. “And within that hypervigilance, where I’m always assessing everything, I might see a behavior or something that sticks out. Then that might spark an idea.”

You see, Sruli has never been easy to place in a box. He’s been coined an artist, designer, futurist, mad scientist, provocateur—a blend of all the above. And he’s an individual, mostly unknown in the carry world, whose experimentation has rippled across the industry. A unique talent—more often than not misunderstood—who can operate in both worlds of high art and commercial design, oscillating somewhere in the middle.

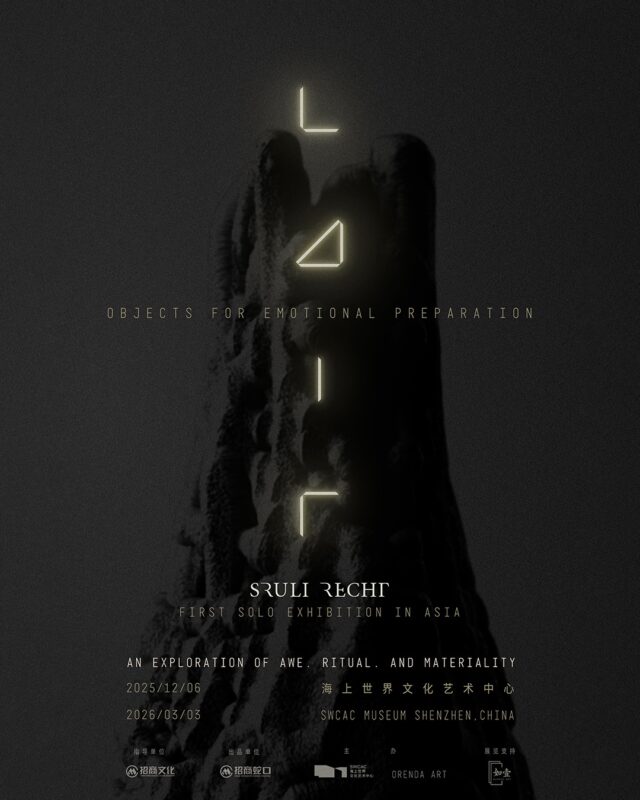

When I reach him, he’s preparing a 68-piece show focused on what he calls “the choreography of the senses.” “We’re taking the idea of what we call ‘immersive art’—which is commonly just folks inside a room full of screens—and relocating the experience internally in the audience. The audience experiences uncertainty. I put them into flow state. I take them through tension, compression, and release.”

In the 1,200-square-foot space, some pieces are made by turning seawater into stone. Some are bee-skin fur. Some combine hydrogen and oxygen gas so that droplets appear out of nothing.

Slowly Futuring

In his formative years, Sruli was shaped by science fiction authors and their thinking beyond the here and now: the cyberspace of William Gibson, the speculative futurism of Bruce Sterling, the philosophical enquiry of Philip K. Dick.

“I’ve usually been inspired by the written word,” he says. “But if you look at those examples, that’s humans thinking beyond the barriers of normal. Like, what else is possible, right? Just beyond. There’s this interesting idea—I remember reading it in an architecture book—that we imagine the unknown on a scale of the already known, on the model of the already known.”

When I ask what drives him, it’s not to challenge the status quo, or to innovate, or shock, or make a beautiful object. He simply pursues a feeling. His eyes and senses scan and comb over his environment in constant search of a spark. And when he locates something, it’s that visceral moment—when his hair stands on end—that he knows he’s found a thread to tease out. The output and variety with which he gushes forth his work is hard to match. He’s launched footwear, clothing lines, glassware, jewellery, spearheaded completely new textiles, and developed renewable materials from seawater using computational design and robotic fabrication.

“I exist between two states,” he says. “My work is not art. It’s not design. I think if you look at it from this idea where art asks questions and design offers a solution—I like to make the thing in the middle that asks a question and shows a solution. It’s in tension. It’s a didactic moment. It explains itself to you and then it becomes conversation. It becomes discursive.”

Across interviews and his own writings, Sruli has consistently framed his work not as fashion but as a form of inquiry—a way to investigate what materials, objects, and garments can say about identity, survival, and the human condition. In conversation with critics and collaborators, he has described design as “a forensic science.” What he seeks is not comfort or luxury—at least, not as commonly defined—but honesty, risk, and challenge. Materials are tools for stories. Objects are experiments. Garments are vessels of philosophy.

When making objects, he explains: “I don’t like having the same thing as other people, and so when I design I have that in mind. The easiest way to achieve that is surface treatment. If I was making glassware, I’d create a unique texture or use anodization. If I was making luggage, I would pick leather that was not uniform in surface so that every bag would have some kind of difference. What I’m looking for is something stochastic—the random probability distribution of a pattern. Let’s say you have 500 grains of sand in a bucket and you shake it a little bit and there’s a pattern, right? And you keep shaking it and there’s a new pattern. So there’s always 500 grains of sand, but the pattern you can stochastically shift.”

His formal education in fashion came at RMIT University in Melbourne. From there, a circuitous path through London—where he worked briefly at Alexander McQueen in 2005—eventually brought him to Reykjavík, Iceland, where his studio and creative practice would take root. Even during his time at McQueen, his atypical approach was already emerging: he simultaneously exhibited giant holograms of his work in galleries across Australia, blurring the boundaries between fashion and fine art from the very beginning.

Once in Iceland, he established the Armory—his showroom and design studio that Wallpaper magazine would name “one of the 10 most interesting clothing shops in the world.” Here, he embraced a production philosophy he dubbed the “Non-Product”: handcrafted or small-run pieces, often too unusual or conceptual to make sense in mass production—not out of elitism, but as a rejection of waste, standardization, and disposability.

By the late 2000s, Sruli had developed a reputation as a designer unafraid to provoke. His work was described as “playfully sinister and beautiful in a slightly disturbing way.” He didn’t limit himself to garments. In 2009, police raided the Armory looking for weapons after discovering he was producing the Umbuster: a knuckle duster and umbrella hybrid. Though the charges were eventually dropped, the incident exemplified the transgressive nature of his work.

This edginess was never for shock alone—but as a lens, a way to force us to confront uncomfortable aspects of desire, identity, vulnerability, and the fragility of comfort. His website and archives reveal numerous other provocative works: shark skin gloves designed to lock your hand in place “in the manner of 10,000 fish hooks,” for example—each piece designed to challenge our assumptions about what is acceptable in fashion and why.

Another breakthrough came with his spider silk T-shirt: a garment made from silk produced by goats genetically modified with spider silk glands implanted into their milk ducts. The result was a fibre that is, by weight, stronger than steel, yet produces a final garment that is incredibly delicate and luxurious. Years later, Japanese lab Spiber took inspiration from the creation of spider silk to develop something called Brewed Protein, which synthesizes similar characteristics and has since been used by brands like Goldwin and The North Face.

The Shift to Material Innovation

In 2015, he shifted his energy to material innovation and joined the experimental-lab side of ECCO Leather, following his participation in their annual “Hotshop” program. The Hotshop—a sort of R&D sandbox—gave him access to advanced tanning facilities, technical expertise, and freedom to experiment at scale.

What followed was a series of ambitious material-development projects. First among them was the creation of a commercially viable translucent leather—dubbed Apparition Leather—combining transparency, suppleness, and workability on a scale never before achieved.

Then came the first commercial mycelium ‘mushroom’ leather, something he still believes isn’t quite there yet.

And then came a conversation with friend Conroy Nachtigall over the phone, a key figure in the development of Arc’teryx Veilance, about a ‘what if’ idea of an ultra-thin leather belt. A year later, Sruli took that light bulb moment and began a practical pursuit: combining leather with Dyneema®, an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene used in aerospace, ballistic protection, and other high-performance applications.

Sruli proposed bonding Dyneema to ultra-thin split leather—a concept that industry professionals initially greeted as unrealistic. But Sruli never really works in the ‘real,’ now does he?

The Alchemy of Dyneema® Leather

“What’s interesting about leather is the emotional connectivity. And utility. History. And the emotional aesthetic,” Sruli explains. “We’ve used leather almost forever—as long as humans have been doing stuff with our hands. We’ve been twisting stuff. It’s like twine to make rope to make baskets to make material. And skinning animals and putting the hides on ourselves. This goes all the way back, so we are so intrinsically tied to the tactility of leather.”

The challenge was clear: how do you honor that ancient connection while pushing the material into the future?

“I thought, if we could shave the leather down to a 0.5-millimeter substance—so the thickness of the leather is 0.5, basically you could pull this apart, it’s just fiber at this point—and then bond it to the thinnest, strongest material in the world, we essentially have leather 3.0 or whatever.”

He pauses, then adds: “That’s basically where the idea came. It was like, how do we make the thinnest, lightest, strongest?”

The development of Dyneema® Bonded Leather was painstaking. The challenge was not simply to fuse two incompatible materials, but to produce a composite that retained the tactile qualities and emotional resonance of leather while inheriting the strength, lightness, and durability of Dyneema.

Sruli and his team at ECCO went through multiple phases of experimental tanning, bonding, and finishing. Leather was skived to the thinnest viable thickness. Dyneema composite fabric was bonded and cured. Then the material underwent careful secondary tanning to ensure softness, handle, and workability.

He recalls that when the first swatches landed in his hands, they defied expectation—”thin, light, wrinkly, and matte.” They floated almost like paper, unlike any leather he’d felt before. He and senior developer Flavia Bon immediately moved to prototype mode, producing an oversized duffel bag that in conventional leather would have weighed five to six kilograms—but here weighed only 200 grams. In that moment, the potential was unmistakable.

A New Class of Material

The result: a new class of material. Dyneema® Leather isn’t a compromise—it’s an expansion. It keeps the emotional gravity and aesthetic of leather while introducing performance characteristics that belong to engineering, not fashion. Strength beyond expectation. Feather-light weight. Extraordinary versatility. Some who worked with him described it as “intergalactic”—”athletic and technical, unbreakable,” with a handle and physics that redefine what leather can do.

Success was more than technical. Dyneema® Leather opened possibilities: from rugged travel bags to protective outerwear, from minimalist fashion to gear for harsh environments. It demonstrated that for Sruli Recht, design is not just about aesthetic statements—it’s about taking what exists and reimagining what it can become.

As a creative force, Sruli’s journey has been one of relentless inquiry. He has traversed through his career not existing in a single pocket, but carving out completely new spaces, or existing in the gray area between. And at times, this inability for the world to typecast him has been a challenge. His work and achievements are hard to market. As he said, he finds it hard to fit in. But when you’re not driven by a bottom line or a marketing strategy and let yourself be led by curiosity and a constant pursuit of ‘the feeling’ it evokes, then that’s the bravest thing you can do. Fitting in be damned.

*Sruli Recht’s new show, Lair is now open. *

Public Opening 6 Dec 2025 – 3 Mar 2026 SWCAC, Level 1, Coastal Gallery No. 1187, Wanghai Road, Shouprix, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China