On September 3, 1949, a U.S. Air Force WB-29 aircraft from the 375th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron landed at Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska, with filter paper samples collected east of the Soviet Union’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Tests on the samples showed anomalously high levels of airborne radioactive debris — high enough to be explained only by an atomic explosion.

Intelligence sources in the United States reported that scientists in the Soviet Union were pushing hard to develop a nuclear capability, but it appeared that they were having trouble. The consensus was that the Soviets were still about three years away from completing a working atomic bomb. Nevertheless, the United States began routine monitoring to detect atomic explosions in the Soviet Union.

The radioactive filter …

On September 3, 1949, a U.S. Air Force WB-29 aircraft from the 375th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron landed at Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska, with filter paper samples collected east of the Soviet Union’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Tests on the samples showed anomalously high levels of airborne radioactive debris — high enough to be explained only by an atomic explosion.

Intelligence sources in the United States reported that scientists in the Soviet Union were pushing hard to develop a nuclear capability, but it appeared that they were having trouble. The consensus was that the Soviets were still about three years away from completing a working atomic bomb. Nevertheless, the United States began routine monitoring to detect atomic explosions in the Soviet Union.

The radioactive filter paper samples were flown to a lab in Berkeley, California, and the test results were reported to the Air Force. Independent tests were conducted by the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, by the British Atomic Energy Authority on airborne samples collected north of Scotland, and by the Naval Research Laboratory on rainwater collected in Kodiak, Alaska, and in Washington, D.C. Each of the tests confirmed high levels of radioactivity.

On September 19, Vannevar Bush, then president of the Carnegie Institution, convened a special panel in Washington, D.C. This panel formally concluded that the USSR had exploded its first atomic bomb, code-named Joe-1, on August 29, 1949.

The announcement by President Harry Truman on September 23, 1949, of an atomic explosion by the Soviet Union shocked the nation. Even worse news came out a short time later. Not only did the Soviet Union have the bomb, it had also developed long-range aircraft able to reach the United States via an Arctic route. The United States had no defense against nuclear attack. The Ground Control of Intercept (GCI) radar network developed during World War II had been designed to defend against an attack with conventional weapons, and it had only a limited ability to detect incoming hostile aircraft. A wave of Soviet bombers carrying nuclear weapons would almost certainly succeed in evading detection by these radars.

A sense of fear and helplessness began to pervade the United States. Civil defense groups built air-raid shelters, and parents trained their children for the possibility of a nuclear war. Today, these perceptions and actions might seem unrealistic and excessive, but in 1949 these fears were very real.

The United States had grown accustomed to having a monopoly on nuclear weapons. Americans had felt invulnerable, and efforts to maintain military installations had been reduced to minimal levels. The Soviet Union’s atomic bomb ended this period of complacency, and the USSR became the Red Menace. Stories about Joseph Stalin’s purges and labor camps, though incomplete, further enhanced the feeling of dread. That Stalin might use nuclear weapons seemed entirely plausible.

These perceptions compelled the Department of Defense (DoD) to reevaluate the nation’s defenses against nuclear attack. As a part of the process, the DoD assigned the U.S. Air Force the task of improving the nation’s air defense system. The Air Force, in turn, asked the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for assistance — and this led to the formation of MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

The story of Lincoln Laboratory begins with George Valley. An associate professor in the MIT Physics Department, Valley was well known for his concern over nuclear weapons. In 1949, after learning of the Soviet atomic bomb, Valley became worried about the quality of U.S. air defenses. Conversations with other professors led him to conclude that the United States had virtually no protection against nuclear attack.

In his concern over the possibility of nuclear attack, George Valley was like many Americans. But in his desire to address the problem, he was unique. Valley decided to make the task of securing U.S. air defenses his personal responsibility.

Valley was in an excellent position to evaluate U.S. air defenses. As a member of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board (SAB), he was able to arrange a visit to a radar station operated by the Air Force Continental Air Command. What he saw appalled him. The equipment had been brought back from World War II and was inappropriate for detecting long-range aircraft. Moreover, the operators had received only minimal instruction in the problems of air defense. He was particularly struck by the site’s use of high-frequency (HF) radios; the quality of HF communications is dependent on the state of the ionosphere, which can vary over time and would be severely disturbed in the event of a nuclear explosion.

Following his visit to the radar station, Valley collected more information on U.S. air defenses, none of it reassuring, and then called Theodor von Karman, chairman of the SAB. Von Karman asked Valley to put his concerns in writing, which he did in a letter dated November 8, 1949.

Von Karman relayed Valley’s concerns to General Hoyt Vandenberg, the Air Force chief of staff. Vandenberg instructed his vice chief of staff, General Muir Fairchild, to take immediate action. By December 15, Fairchild had organized a committee of eight scientists, with Valley as the chair, to analyze the air defense system and to propose improvements. On January 20, 1950, the committee, officially named the Air Defense Systems Engineering Committee (ADSEC) but informally known as the Valley Committee, began to meet weekly.

The Valley Committee

The members of the Committee agreed to begin their study with a set of basic assumptions about hostile aircraft and U.S. air defenses. They agreed that a Soviet bomber would most likely fly over the north polar region at high altitude and then descend as it approached its target. While the aircraft flew at high altitude, it would be able to detect ground radar before the radar could detect the aircraft. The bomber could then descend to a low altitude, where it could fly under the beam of the radar and be virtually undetectable. The committee determined that, to attack a city in the United States, a Soviet bomber would need to fly at low altitude for only about 10 percent of its journey. Therefore, the range penalty for low-altitude flight would be small. If aerial refueling were performed near the Arctic Circle, the entire United States could be vulnerable to a Soviet attack. Spaced as they were, the then-existing GCI radars gave virtually no protection. A low-flying aircraft could find a clear path to almost every city in the United States.

The Committee determined that the weakest link in the nation’s air defenses was the radars that were supposed to detect low-flying aircraft. Each radar’s range was limited by its horizon. By flying at low altitude, aircraft could hide from the widely spaced GCI radars. Since air-based or space-based surveillance was not an option in 1950, the only solution was to install ground-based radar systems close together.

In 1950, this solution was ambitious. But fortunately for the future Lincoln Laboratory, the Committee continued to evaluate the problem and reduced it to two major issues. First, in order to interpret the signals from a large number of radars, there had to be a way to transmit the radar data to a central computer at which the data could be aggregated. Second, since the objective was to detect and intercept the hostile aircraft, the computer had to analyze the data in real time.

When Valley called several computer manufacturers to inquire about the possibility of using one of their systems to test his ideas, he was dismissed as a crackpot. Real-time operation was simply inconceivable in 1950. However, the answers to the problems of data transmission and of real-time operation were waiting to be addressed nearby. At the Air Force’s Cambridge Research Laboratory, John Harrington had developed an early form of modem known as the digital radar relay, which was capable of converting analog radar signals into digital code that could be transmitted over telephone lines. Also, at the Servomechanisms Laboratory on the MIT campus, Jay Forrester was heading up a group that was developing the world’s first real-time computer.

Valley needed a computer fast enough to handle real-time data analysis. As he began his search, Valley ran into Professor Jerome Wiesner, then associate director of the Research Laboratory of Electronics, and learned that the computer he required was already on the MIT campus. It was in the Servomechanisms Laboratory, and it was about to be abandoned by its sponsor.

During World War II, the emphasis in the Servomechanisms Laboratory had been on developing gun-positioning instruments. After the end of the war, the laboratory had begun a program to demonstrate a flight simulator for the Office of Naval Research. Plans had called for this device to simulate virtually every aircraft then in existence. Because this would require a powerful computer, the Servomechanisms Laboratory had begun to develop its own computer, code-named Whirlwind.

From his talk with Forrester, Valley was convinced that Whirlwind was suited to the ADSEC project. From then on, Forrester was a regular participant in ADSEC. Whirlwind was in a relatively early stage of its construction, with only 5 words of random-access memory and 27 words of programmable read-only memory. Yet its high speed and 16-bit word length made it adequate for ADSEC to test the feasibility of the concept that radar data could be transmitted to a computer via the digital radar relay, and that the computer could respond to the information in real time and direct an interception.

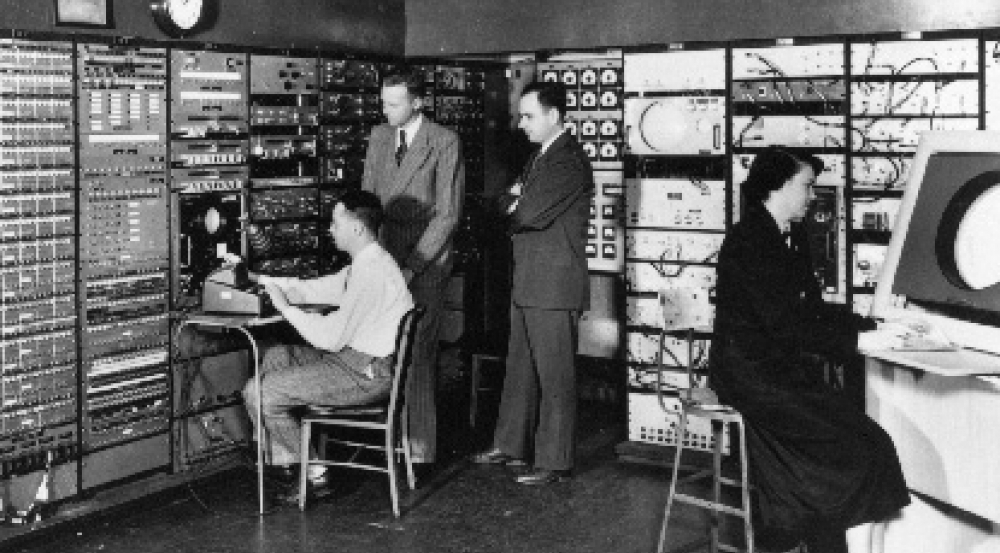

The Whirlwind computer console room in MIT’s Barta Building in 1950; Jay Forrester, second from left, and Robert Everett, second from right.

Forrester promptly began preparing to receive and process digitized radar signals. The feasibility demonstration of the radar/digital-data concept took place at Hanscom Field in September 1950. The radar, which was an original experimental model of a microwave early-warning unit built by the wartime MIT Radiation Laboratory, closely resembled the radars used in the D-Day invasion of Normandy. While military observers watched closely, an aircraft flew past the radar, the digital radar relay transmitted the signal from the radar to Whirlwind via a telephone line, and the result appeared on the computer’s monitor. The demonstration was a complete success and proved the feasibility of ADSEC’s air defense concept.

The demonstration at Hanscom Field signaled the end of the first phase of ADSEC’s work. The committee’s focus shifted from evaluation to implementation; a laboratory dedicated to air defense problems began to be discussed.

On November 20, 1950, Louis Ridenour, chief scientist of the Air Force, wrote in a memo to Major General Gordon Saville, deputy chief of staff for development in the Air Force, "It is now apparent that the experimental work necessary to develop, test, and evaluate the systems proposals made by ADSEC will require a substantial amount of laboratory and field effort."

Ridenour’s memo was the first document to propose a laboratory dedicated to air defense research. He estimated that such a laboratory would require a staff of about 100 and a budget of about $2 million per year. (During the 1950s, Lincoln Laboratory actually would have a staff of about 1800 and an annual budget in excess of $20 million.)

A few weeks later, on December 15, Valley joined Ridenour for lunch at the Pentagon. Ridenour persuaded Valley that they should ask MIT to set up the electronics laboratory that could develop ADSEC’s air defense ideas. Valley later recalled that he wrote a letter in about an hour and that Ridenour recast it in "appropriate general officer’s diction." By four o’clock, the letter had been signed by General Vandenberg and was on its way to James Killian, Jr., president of MIT.

The Vandenberg letter to Killian contained the following text:

The Air Force feels it is now time to implement the work of the part-time ADSEC group by setting up a laboratory which will devote itself intensively to air defense problems…

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is almost uniquely qualified to serve as contractor to the Air Force for the establishment of the proposed laboratory. Its experience in managing the Radiation Laboratory of World War II, the participation in the work of ADSEC by Professor Valley and other members of the MIT staff, its proximity to AFCRL [Air Force Cambridge Research Lab] and its demonstrated competence in this sort of activity have convinced us that we should be fortunate to secure the services of MIT in the present connection.

The air defense problem which faces the Air Force is of great importance to the people of this country. The problem is technically complicated and difficult. The Air Force must urgently increase its research and development effort in this area and in this we ask your help. I sincerely hope that you will be able to give the matter serious consideration.

MIT Establishes the New Laboratory

Project Charles

MIT President James Killian had serious reservations about MIT starting up a new laboratory because MIT had "devoted itself so intensively to the conduct of the Radiation Laboratory and other large war projects."

Louis Ridenour, chief scientist of the U.S. Air Force, provided President Killian with a reason for setting up a laboratory that, although unrelated to national defense, was particularly persuasive. Ridenour suggested that a laboratory to address air defense problems would serve as a stimulus for the nation’s small electronics industry. He predicted that the state that became the home of the new laboratory would emerge as a center for the electronics industry. Ridenour’s words were prophetic, as evidenced by the growth of the electronics and computer industry along Route 128, the circumferential highway around Boston.

Because Killian was not eager for MIT to become involved in air defense, he asked the Air Force if MIT could first conduct a study to evaluate the need for a new laboratory and to determine its scope. Killian’s proposal was approved, and a study named Project Charles (for the river that flows past MIT) was carried out between February and August 1951.

Project Charles was conducted by a group of 28 scientists, 11 of whom were associated with MIT. The director was F. Wheeler Loomis, the University of Illinois professor who subsequently became Lincoln Laboratory’s first director. Albert Hill and Carl Overhage, also members of the study, became the Laboratory’s second and fourth directors, respectively. Most of the other members of Project Charles also went on to join the Laboratory.

The Final Report of Project Charles stated that the United States needed an improved air defense system and that Valley had developed the correct plan: "We endorse the concept of a centralized system as proposed by the Air Defense Systems Engineering Committee, and we agree that the central coordinating apparatus of this system should be a high-speed electronic digital computer."

Project Charles came out unequivocally in support of the formation of a laboratory dedicated to air defense problems:

Experimental work on certain of these problems is planned in a laboratory to be operated by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology jointly for the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force, to be known as PROJECT LINCOLN.1

This statement was the approval by a technically trained panel that President Killian had wanted. The decision to found the new laboratory, with the unusual support of all three services, became final.

1 Problems of Air Defense: Final Report of Project Charles, Vol. I. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1951, p. x.

Project Lincoln

The Charter for the Operation of Project Lincoln stated that the Air Force was to build a laboratory where the Massachusetts towns of Bedford, Lexington, and Lincoln meet. Why the name Lincoln? There had already been a Project Bedford (on antisubmarine warfare) and a Project Lexington (on nuclear propulsion of aircraft), so Major General Putt, who was in charge of drafting the Charter, decided to name the project for the town of Lincoln.

F. Wheeler Loomis took over as director of Project Lincoln. He had a small staff, unsure funding, and a promise to construct a laboratory. Moreover, he faced an immense challenge — to design a reliable air defense system for the continent of North America. Before Loomis could begin to hire the staff for Project Lincoln, he had to set up a structure for the organization. For this, he drew upon a model originated by the Radiation Laboratory in 1942. The organizational structure he followed consisted of a director’s office, a steering committee, and a staff divided into divisions and groups. Each division was in charge of developing a system, and each group designed a component of that system. The concept of divisions and groups proved effective and efficient. Its simplicity enabled Project Lincoln to operate with far fewer managers and with far less internal politics than many other organizations. In fact, the structure worked so well that it has remained in use in Lincoln Laboratory to this day.

Project Lincoln was divided into five technical divisions: aircraft control and warning, communications and components, weapons, special systems, and digital computers. It also had two service divisions: business administration and technical services. The divisions were divided into one to six groups. Each division examined one aspect of the continental air defense problem; each group looked at one element of its division’s task.

By September 1951, Project Lincoln had more than 300 employees. Within a year, it employed 1,300. One year later, Lincoln Laboratory had grown to 1,800 personnel, a level that would remain fixed for several years.

With staff coming on board and the funding secure, Loomis now turned his attention to the construction of buildings. The space on the MIT campus was already inadequate, and hundreds of employees were joining the project. The sole site available on campus for classified work was Building 22.

Unclassified research was carried out in Building 20, and administrative offices of Project Lincoln were located in the Sloan Building at MIT. Temporary housing for the motor pool, the electronics shops, and the publications office was found in a two-story commercial building on Vassar Street. Although the MIT Digital Computer Laboratory (originally part of the Servomechanisms Laboratory) became part of Project Lincoln, work on Whirlwind continued to be carried out in the Barta Building on Massachusetts Avenue and in the Whittemore Building on Albany Street.

Space was not the only issue. President Killian believed that MIT should not be carrying out classified research on the Cambridge campus. He thought that MIT had an obligation to disseminate its research results throughout the academic community and that classified research was inherently incompatible with this obligation. Therefore, Killian wanted MIT to maintain its integrity by conducting Project Lincoln off campus. The Bedford-Lincoln-Lexington area mentioned in the Charter for the Operation of Project Lincoln had space for new construction, and it was a comfortable distance from Cambridge.

This site was the Laurence G. Hanscom Field, now Hanscom Air Force Base and still the home of Lincoln Laboratory. Hanscom Field became a Commonwealth of Massachusetts facility in May 1941, when the state legislature acquired 509 acres for the construction of an airport. It was located in part in each of the towns of Concord, Lincoln, Lexington, and Bedford, on a flat area between the Concord and Shawsheen rivers. The official groundbreaking ceremony for the airfield, then known simply as the Boston Auxiliary Airport at Bedford, was held on June 26, 1941.

Lincoln Laboratory

Groundbreaking for Project Lincoln began in 1951 at the foot of Katahdin Hill in Lexington. The site lay directly below 47 acres of farmland that had been acquired by MIT in 1948 as a site for cosmic-ray research. Twenty-six acres were transferred to the Army, and the remaining 21 acres were assigned to Project Lincoln.

The new buildings were laid out in an open-wing configuration, with alternate wings along a central axis. The plans called for four wings (Buildings A, B, C, and D) plus a concrete block utility structure (Building E).

The Boston firm of Cram and Ferguson was chosen as the architect. Although the firm was among the oldest and largest of its kind in the United States, it was not generally associated with laboratory construction. In fact, the firm was better known for Gothic and art deco architecture, such as the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City and the 1948 John Hancock Building in Boston.

Cram and Ferguson came up with a modular design for the buildings, with each staff member allotted 9 × 9 square feet. The main corridor of each building was 400 feet long, which yielded 44 modules along each side. Supporting columns were spaced 18 feet apart, and movable partitions were used for the internal walls.

Initial construction of Lincoln Laboratory, October 1952.

Buildings were 60 feet wide, with 15 feet wide corridors. Because laboratories required more space than offices, modules were 18 feet deep on one side of the corridor and 27 feet deep on the other. Buildings B and C each had four stories, three above and one below ground level. Buildings A and D had three stories, and the lowest levels were only partially below ground. Building E had a single story and a small basement. It held the receiving room, stockroom, storage area, shops, and garage.

Building B was completed barely two years after the first meeting of ADSEC and less than a year after the Project Charles Final Report. The scientists and engineers working on Project Lincoln were talented indeed, as are so many working at Lincoln Laboratory today. But the MIT Radiation Laboratory had instituted procedures that were remarkably free of red tape, and this was its legacy to Project Lincoln.

Lincoln Laboratory in 1956.

Fear of nuclear holocaust pervaded the thinking of Americans in the 1950s, and the government of the United States was committed to protecting the country against this threat. Because Project Lincoln’s mission was vital to the security of the nation, red tape was eliminated at all stages.

The Air Force had put its resources at the disposal of Project Lincoln. Now, the staff had only one more problem to solve: they had to deliver a reliable air defense system for North America.

The scope of the SAGE Air Defense System, as it evolved from its inception in 1951 to its full deployment in 1963, was enormous. The cost of the project, both in funding and the number of military, civilian, and contractor personnel involved, exceeded that of the Manhattan Project. The project name evolved over time from Project Lincoln, its original 1951 designator, to the Lincoln Transition System, and finally settled out as the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, or SAGE.

The basic SAGE architecture was cleanly summarized in the preface to a seminal 1953 technical memo written by George Valley and Jay Forrester: Lincoln Laboratory Technical Memorandum No. 20, A Proposal for Air Defense System Evolution: The Transition Phase.

Briefly, the… system will consist of: (1) a net of radars and other data sources and (2) digital computers that (a) receive the radar and other information to detect and tract aircraft, (b) process the track data to form a complete air situation, and (c) guide weapons to destroy enemy aircraft.

The concept of operations for SAGE was fairly simple and was similar to that of modern automated air defense systems. However, it was pioneering at the time. A large network of radars would automatically detect a hostile bomber formation as it approached the U.S. mainland from any direction. The radar detections would be transmitted over telephone lines to the nearest SAGE direction center, where they would be processed by an AN/FSQ-7 computer. The direction center would then send out notification and continuous targeting information to the air bases best situated to carry out interception of the approaching bombers, as well as to a set of surface-to-air missile batteries. The direction center would also send data to and receive data from adjoining centers, and send situational awareness information to the command centers. As the fighters from the air bases scrambled and became airborne, the direction center would continue to process track data from multiple radars and would transmit updated target positions in order to vector the intercepting aircraft to their targets. After the fighter aircraft intercepted the approaching bombers, they would send raid assessment information back to the direction center to determine whether additional aircraft or missile intercepts were necessary.

SAGE animation by Chester Beals, copyright MIT Lincoln Laboratory, 2009.

- Early warning radar detects approaching aircraft

- Radar reports automatically transmitted to direction center (DC) via phone lines

- DC processes data

- Air bases, HQs, and missile batteries notified

- Data relayed between DC and adjoining centers

- DC assigns interceptor aircraft and vectors interceptors to targets

- Interceptors rendezvous with and intercept targets

- DC informs HQ of results; missile batteries provide second line of defense if needed

The SAGE system, by the time of its full deployment, consisted of 100s of radars, 24 direction centers, and 3 combat centers spread throughout the U.S. The direction centers were connected to 100s of airfields and surface-to-air missile sites, providing a multilayered engagement capability. Each direction center housed a dual-redundant AN/FSQ-7 computer, evolved from MIT’s experimental Whirlwind computer of the 1950s. These computers hosted programs that consisted of over 500,000 lines of code and executed over 25,000 instructions — by far the largest computer programs ever written at that time. The direction centers automatically processed data from multiple remote radars, provided control information to intercepting aircraft and surface-to-air missile sites, and provided command and control and situational awareness displays to over 100 operator stations at each center. It was far and away the most grandiose systems engineering effort — and the largest electronic system-of-systems "ever contemplated."

Although the basic concept for SAGE was simple, the technological challenges were immense. One of the greatest immediate challenges was the need to develop a digital computer that could receive vast quantities of data from multiple radars and perform the real-time processing to produce targeting information for intercepting aircraft and missiles. Fortunately, and serendipitously, the initial concept development for such a computer was taking place on the MIT campus in the Servomechanisms Laboratory, under the direction of Jay Forrester. This effort, with its maturation under SAGE, laid the foundation for a revolution in digital computing, which subsequently had a profound impact on the modern world.

By 1952, the basic concept for the air defense project was approaching a degree of maturity. A radar network had been assembled, and Lincoln Laboratory was ready to begin testing. MIT’s Whirlwind computer showed promise for providing the real-time computational capability needed for SAGE. However, the reliability of the computer still posed a significant problem. Before plans for a nationwide air defense system could be taken seriously, the computer would have to become much more reliable.

**Magnetic-Core Memory **

One of the most significant limitations of computers at the time was the storage tubes that were used for internal memory. These tubes were large and slow, and worst of all, they were unreliable. One of the greatest breakthroughs in the development of Whirlwind was the invention of magnetic-core memory. That invention was the key development leading to the widespread adoption of computers for industrial applications because, unlike computers with storage-tube memories, computers with magnetic-core memories were reliable.

In 1947, while working on Whirlwind in the MIT Servomechanisms Laboratory, Jay Forrester began to think about developing a new type of memory. He conceived of a new way of configuring memory units — in a three-dimensional structure. Although Forrester initially thought of using glow-discharge tubes, preliminary tests indicated that these tubes were too unreliable. Lacking a good way to implement a three-dimensional memory, Forrester dropped work on his concept for a couple of years. Then, in the spring of 1949, he saw an advertisement from the Arnold Engineering Company for a reversibly magnetizable material called Deltamax. Forrester immediately recognized that this was the material he needed for the three-dimensional memory structure.

Forrester directed one of his students, William Papian, to study combinations of small toroidal-shaped cores made of ferromagnetic materials possessing suitable hysteresis loop characteristics. Papian’s master’s thesis, A Coincident-Current Magnetic Memory Unit, completed in August 1950, described the concept of magnetic-core memories and showed how the cores could be combined in planar arrays, which could in turn be connected into three-dimensional assemblies. Papian fabricated the first magnetic-core memory, a 2 × 2 array, in October 1950. The early results were encouraging, and by the end of 1951 a 16 × 16 array of metallic cores was completed.

The organization and direction of Project Whirlwind now went through a major change. The task of developing a flight simulator was abandoned, and the focus of the program shifted to air defense. In September 1951, all members of the Servomechanisms Laboratory who were working on Whirlwind were assigned to a new laboratory — the MIT Digital Computer Laboratory, headed by Jay Forrester. Six months later, the Digital Computer Laboratory was absorbed by Lincoln Laboratory as the Digital Computer Division. Lincoln Laboratory took over the development of magnetic-core memories.

Operation of the early metallic magnetic-core memories was still unsatisfactory — switching times were 30 µsec or longer. Therefore, in cooperation with the Solid State and Transistor Group, Forrester began an investigation of ferrites. These nonconducting magnetic materials had weaker output signals than did the metallic cores, but their switching times were at least ten times faster. In May 1952, a 16 × 16 array of ferrite cores was operated as a memory, with an adequate signal and a switching time of less than a microsecond. So promising was the performance of the new array that the Digital Computer Division began construction of a 32 × 32 × 6 memory, the first three-dimensional memory.

Whirlwind was by this time in considerable demand, so a new machine called the Memory Test Computer was built to evaluate the 16,384-bit core memory. When the Memory Test Computer went into operation in May 1953, the magnetic-core memory, in sharp contrast to the electrostatic-storage-tube memory in Whirlwind, was highly reliable. Forrester promptly removed the core memory from the Memory Test Computer and installed it in Whirlwind.

The first bank of core storage was wired into Whirlwind on August 8, 1953. A month later, a second bank went in. A different memory was subsequently installed in the Memory Test Computer, enabling that machine to be used in other applications.

The improvement in Whirlwind’s performance was dramatic. Operating speed doubled; the input data rate quadrupled. Maintenance time on the memory dropped from four hours per day to two hours per week, and the mean time between memory failures jumped from two hours to two weeks.

The invention of core memory was a watershed in the development of commercial computers. The technology was quickly adopted by International Business Machines (IBM), and the first nonmilitary system to use magnetic-core memories, the IBM 704, went on the market in 1955. Magnetic cores were used in virtually all computers until 1974, when they were superseded by semiconductor integrated-circuit memories.

Computers were in their infancy when George Valley first approached Jay Forrester to discuss developing an air defense network, and the industrial base needed to develop the required computing capability simply did not exist. Therefore, in addition to prototyping and testing the first real-time digital computers, the Project Lincoln staff had to cultivate the industrial infrastructure needed to bring a nation-wide air defense system into being. The result was that the SAGE program became a driving force behind the formation of the American computer and electronics industry in the 1950s.

The modular computer architecture, first developed by Ken Olsen as a staff member at Lincoln Laboratory, became a key part of the programmed data processor (PDP) minicomputer which Olson popularized through the company that he founded, the Digital Equipment Corporation. In addition, the contract to build the AN/FSQ-7 played a sizable role in the metamorphosis of IBM from a business machine vendor to the world’s largest computer manufacturer.

The breakthroughs that came about through the course of the SAGE program initiated, to a large extent, the digital computing revolution that has had such a significant impact on today’s world.

The AN/FSQ-7 Computer

The Whirlwind project at MIT’s Digital Computer Laboratory had demonstrated real-time control, the key ingredient for the Project Lincoln air defense concept. Whirlwind also provided an experimental test bed for the system design. By the spring of 1952, Whirlwind was working well enough to be used as part of the early air defense prototyping activities. The focus of the program within the Digital Computer Division shifted, therefore, to development of a production computer, Whirlwind II.

Whirlwind I was more of a breadboard than a prototype of a computer that could be used in the air defense system. The Whirlwind II group dealt with a wide range of design questions, including whether transistors were ready for large-scale employment (they were not) and whether the magnetic-core memories were ready for exploitation as a system component (they were). The most important goal for Whirlwind II was that there should be no more than a few hours of down time per year.

The AN/FSQ-7 computer was designed by joint Lincoln Laboratory and IBM committees that managed to merge the best elements of their members’ diverse backgrounds to produce a result that advanced the state of the art in many directions.

To turn the ideas and inventions developed in the Whirlwind program into a reproducible, maintainable operating device required the participation of an industrial contractor. A team, led by Jay Forrester, was set up to evaluate potential contractors. This team was responsible for finding the most appropriate computer designer and manufacturer to translate the progress made in Project Lincoln into a design for an operational air defense system. The team surveyed the possible engineering and manufacturing candidates and chose three for further evaluation: IBM, Remington Rand, and Raytheon. They visited each company, reviewed its capabilities, and graded each on the basis of personnel, facilities, and experience.

IBM received the highest score and was issued a six-month subcontract in October 1952. Over the next few months, the IBM group visited Lincoln Laboratory frequently to study the system being developed, to become acquainted with the overall design strategy, and to learn the specifics of the central processor design.

In January 1953, system design for Whirlwind II began in earnest. The computer was designed by joint Lincoln Laboratory and IBM committees that managed to merge the best elements of their members’ diverse backgrounds to produce a result that advanced the state of the art in many directions.

The schedule was tight. Lincoln Laboratory set a target date of January 1, 1955, to complete the prototype computer and its associated equipment. Installation, testing, and integration of the equipment in the air defense system were scheduled to be started on July 1, 1954. The nine months preceding this, October 1, 1953, to July 1, 1954, would be needed for procurement of materials and construction. The schedule left about nine months for engineering tasks in connection with the preparation of specifications, block-diagram work, development of basic circuit units, special equipment design, and everything else necessary before construction could begin.

In April 1953, IBM received a prime contract to design the computer. A short time later, the name Whirlwind II was dropped in favor of Air Force nomenclature, and the computer was designated AN/FSQ-7. In September, IBM received a contract to build two single-computer prototype systems, AN/FSQ-7(XD-l) and AN/FSQ-7(XD-2). (The XD stands for experimental development.) The AN/FSQ-7(XD-l) replaced Whirlwind in the prototype air defense system during 1955. IBM kept the AN/FSQ-7(XD-2) in Poughkeepsie, New York, and used the machine to support software development and to provide a hardware test bed.

As the plans for the continental air defense system began to take shape, it became evident to the Air Force that automating the combat centers would be desirable. (Each combat center directed operations and allocated weapons for several direction centers.) The combat centers needed a computer like the AN/FSQ-7 but with a specialized display system; this system was named the AN/FSQ-8. The AN/FSQ-8 display console could show the status of an entire sector. Its inputs and outputs did not handle radar or other field data, but were dedicated to communication with direction centers and with higher-level headquarters.

IBM received its first production contract in February 1954. The first AN/FSQ-7 was declared operational at McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey, on July 1, 1958. IBM eventually manufactured 24 AN/FSQ-7s and 3 AN/FSQ-8s. Each AN/FSQ-7 weighed 250 tons, had a 3,000-kilowatt power supply and required 49,000 vacuum tubes. To ensure continuous operation each computer was duplexed; it actually consisted of two machines. The percentage of time that both machines in a system were down for maintenance was 0.043 percent, or 3.77 hours averaged over a year.

Software Development

In addition to the computer hardware, a large part of the air defense project effort was devoted to software development. The software task developed quickly into the largest real-time control program ever coded, and all the coding had to be done in machine language since higher-order languages did not yet exist. Furthermore, the code had to be assembled, checked, and realistically tested on a one-of-a-kind computer that was a shared test bed for software development, hardware development, demonstrations for visiting officials, and training of the first crew of Air Force operators.

The art of computer programming was essentially invented for SAGE.

Computer software was in an embryonic state at the beginning of the SAGE effort. In fact, the art of computer programming was essentially invented for SAGE. Among the innovations was more efficient programming (both in terms of computer run time and memory utilization), which was achieved through the use of generalized subroutines and which allowed the elimination of a one-to-one correspondence between the functions being carried out and the computer code performing these functions. A new concept, the central service (or bookkeeping) subprogram, was introduced.

Documentation procedures provided a detailed record of system operations and demonstrated the importance of system documentation. Checkout was made immensely faster and easier with utility subprograms that helped locate program errors. These general-purpose subprograms served, in effect, as the first computer compiler. The size of the program — 25,000 instructions — was extraordinary for 1955; it was the first large, fully integrated digital computer program developed for any application. Whirlwind was equal to the task: between June and November 1955, the computer operated on a 24-hour, 7-day schedule with 97.8 percent reliability.

Because of the complexity of the software, Lincoln Laboratory became one of the first institutions to enforce rigid documentation procedures. The software creation process included flow charts, program listings, parameter and assembly test specifications, system and program operating manuals, and operational, program, and coding specifications. About one-quarter of the instructions supported operational air defense missions. The remainder of the code was used to help generate programs, to test systems, to document the process, and to support the managerial and analytic chores essential to good software.

These programs were large, and because MIT did not want further increases in the Lincoln Laboratory staff, the Rand Corporation was asked to assist in the programming task. Rand was eager to play a role in the SAGE effort and began work on the software in April 1955. By December, the section of Rand in charge of SAGE programming — the System Development Division — had a staff of 500. Within a year, the System Development Division had a staff of a 1,000 and was larger than the rest of Rand put together. The Division left its parent company in November 1956 and formed the nonprofit System Development Corporation, with a $20 million contract to continue the work started by Rand and with additional contracts for programming the SAGE computers. SAGE had spawned another company, and another industry.

While the Digital Computer Division at Lincoln Laboratory wrestled with Whirlwind, the Aircraft Control and Warning Division concentrated its efforts on verifying the underlying concepts of air defense. A key recommendation in the Project Charles Final Report was that a small air defense system should be constructed and evaluated before work on a more extensive system began. The report proposed that the experimental network be established in eastern Massachusetts, that it include 10 to 15 radars, and that all radars be connected to Whirlwind. This methodology of system prototyping, first established during SAGE, became core to Lincoln Laboratory’s approach to the development of new system concepts, and is still very much part of the Laboratory’s culture today.

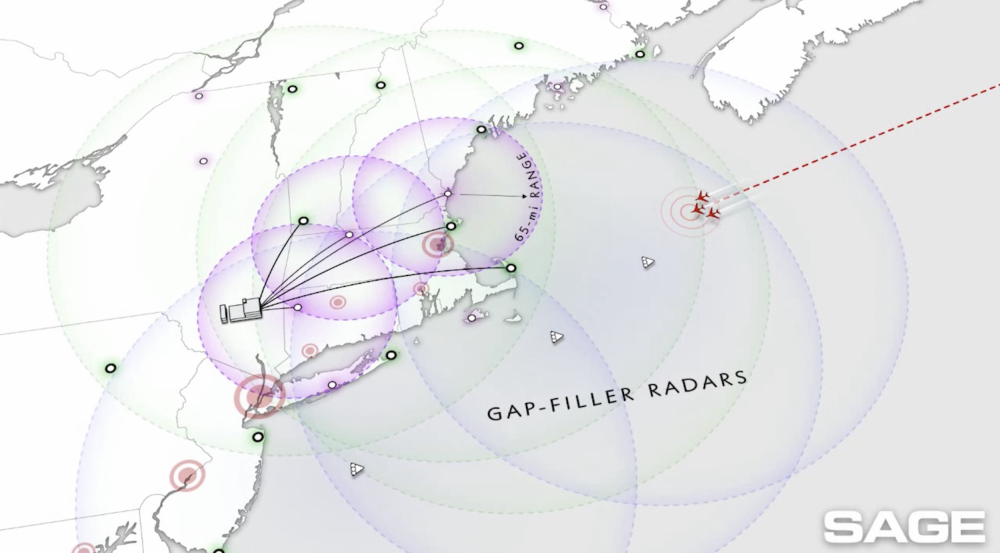

As soon as the air defense program began, Lincoln Laboratory started to set up an experimental system and named it, for its location, the Cape Cod System. It was functionally complete; all air defense functions could be demonstrated, tested, and modified. The Cape Cod System was a model air defense system, scaled down in size but realistically embodying all operational functions.

Cape Cod, which was chosen because of its convenience to the Laboratory, was a good test site. It covered an area large enough for realistic testing of air defense functions. In addition, its location was challenging — hilly and bounded on two sides by the ocean, with highly variable weather and a considerable amount of air traffic.

Every aspect of the Cape Cod System called for innovation. Not only did it require radar netting, but radar data filtering was also needed to remove clutter that was not canceled by the moving-target indicator (MTI). Phone-line noise also had to be held within acceptable limits.

A long-range AN/FPS-3 radar, the workhorse of the operational air defense net, was installed at South Truro, Massachusetts, near the tip of Cape Cod, and equipped with an improved digital radar relay. Less powerful radars, known as gapfillers, were installed to enhance the coverage provided by the long-range system. Because near-total coverage was required, the beams of the radars in the network had to overlap, meaning that the radars could be separated by no more than 25 miles.

Initially, two SCR-584 radars that had been developed during World War II by the MIT Radiation Laboratory were installed as gapfillers at Scituate and Rockport, Massachusetts. Early tests of these radars showed much shorter detection ranges than expected, however, and improvements in the components and the test equipment were required to resolve the problems and make the radars operate as needed. As new radars became operational, each included a Mark-X identification-friend-or-foe (IFF) system, and reports were multiplexed with the radar data. Dedicated telephone circuits to the Barta Building in Cambridge were leased and tested.

Buffer storage had to be added to Whirlwind to handle the insertion of data from the asynchronous radar network, and the software had to be expanded considerably. A direction center needed to be designed and constructed to permit Air Force personnel to operate the system: to control the radar data filtering, initiate and monitor tracks, identify aircraft, and assign and monitor interceptors.

Construction of a realistic direction center depended heavily on the development of an interactive display console. Nothing comparable had ever been done before, and the technology was primitive. What was needed was a computer-generated display that would include alphanumeric characters (to act as labels on aircraft) and a separate electronic tote-board status display. Then, the console operator could select display categories of information (for example, hostile aircraft tracks) without being distracted by all of the information available.

The display console was developed around the Stromberg-Carlson Charactron cathode-ray tube (CRT). The tube contained an alphanumeric mask in the path of the electron beam. The beam was deflected to pass through the desired character on the mask, refocused, and then deflected a second time to the desired location on the tube face. This process was electronically complex, but it worked. The console operator had a keyboard for data input and a light-sensing gun, which was used to recognize positional information and enter it into the computer. This novel means of control for high-speed computers was invented at the Laboratory by Robert Everett.

All these complex engineering tasks were carried out in parallel, on schedule, and with little reworking. By September 1953, just two years and five months after the go-ahead, the Cape Cod System was fully operational. The radar network consisted of gapfiller radars, height-finding radars, and long-range radars.

The software program could handle, in abbreviated form, most of the air defense tasks of an operational system. Facilities were in place to initiate and track 48 aircraft, identify and find the height of targets, control 10 simultaneous interceptions from two air bases, and give early warning and transmit data on 12 tracks to an antiaircraft operations center. Now the system had to be tested.

Testing the Cape Cod System

Formal trials of the Cape Cod System began in October 1953, with flight tests two afternoons a week. The tests continued until June 15, 1954, and analysis of the initial test results was highly favorable. Track initiation, tracking, and identification were accomplished successfully.

Over the next few months, the Cape Cod System was expanded to include long-range AN/FPS-3 radars at Brunswick, Maine, and Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. Additional gapfillers were built and integrated, completing the expanded radar network in the summer of 1954.

Jet interceptors were assigned to support the experiments: 12 Air Force F-89Cs at Hanscom Field and a group of Navy F-3Ds at South Weymouth, Massachusetts. Later, an operational Air Defense Command (ADC) squadron of F-86Ds based at the Suffolk County Airfield on Long Island was integrated into the Cape Cod System, and the Air Force arranged for Strategic Air Command training flights in the Cape Cod area so the Cape Cod System could be used for large-scale air defense exercises against Strategic Air Command B-47 jet bombers.

The time had com