December 25, 2025

5 min read

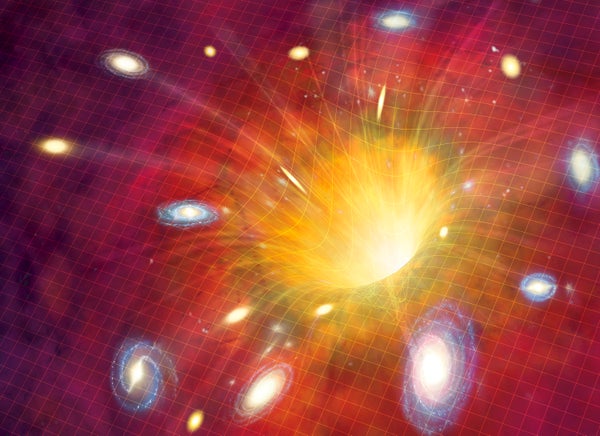

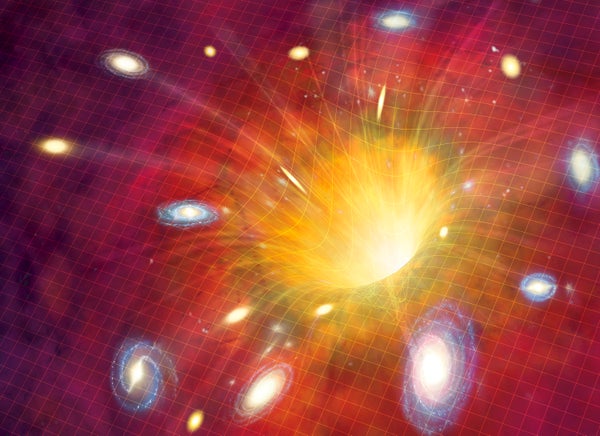

Record-breaking objects can tell us about the most powerful events in the cosmos—sometimes

By Phil Plait edited by Lee Billings

Science Photo Library - MARK GARLICK/Getty Images

As a science communicator, I don’t think a week goes by without a press release hitting my inbox informing me of astronomers finding some new record-breaking object.

…

December 25, 2025

5 min read

Record-breaking objects can tell us about the most powerful events in the cosmos—sometimes

By Phil Plait edited by Lee Billings

Science Photo Library - MARK GARLICK/Getty Images

As a science communicator, I don’t think a week goes by without a press release hitting my inbox informing me of astronomers finding some new record-breaking object.

Sometimes it’s the smallest planet yet discovered or the most iron-deficient star. But a very common claim is a distance record: the farthest galaxy from Earth ever seen, for example.

When it comes to these sorts of record breakers, I have complicated feelings, built over decades of writing about them. Such announcements must be parsed carefully because sometimes they’re not that big of a deal—but sometimes they signal a sea change in what we can do or understand.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Distance records are an excellent proxy for the state of the art in astronomy. Finding extremely faraway galaxies is hard. In general, objects get smaller and fainter with distance (although bizarre exceptions do sometimes apply), so huge telescopes are needed to spot them at all.

Then comes the difficulty of actually determining their distance. We can’t do this directly; it’s not like we can hop onboard the starship Enterprise and keep our eyes on the odometer as we warp our way there. So we gauge distances in other ways.

The most well established method is to observe redshift: The universe is expanding, and as it does so, space sweeps galaxies along with it. Light leaving a distant galaxy loses energy as it fights that expansion, so by the time it reaches us, its wavelength is stretched, which is what astronomers call a redshift. For historical (and mathematical) reasons, we say that a photon with its wavelength stretched out by a factor of two has a redshift of one; if the wavelength is three times longer, the redshift is two, and so on. Because the velocity at which a galaxy recedes from us is related to its distance, finding the redshift of a galaxy can be used to measure that distance.

That’s not an easy task either because converting redshift to distance involves understanding some rather arcane features of the universe—such as how much normal matter, dark matter and dark energy it contains, to name only a few. But we have accurate enough numbers for those parameters to get a decent grasp on distances.

And this is where “record-breaking” really comes in. I’ll sometimes see a paper or announcement about a new galaxy that breaks the previous record—but it’ll have a redshift of, say, 7.34, when the previous record was 7.33. That difference is pretty small! And depending on your preferred values for cosmic parameters, the difference might add up to just a million light-years. In our example of an object at a redshift of 7.34, we’re talking distances of around 13 billion light-years, so the record-breaker is not exactly lapping the other galaxy. Also, it’s not really telling us too much about the nature of the cosmos to simply find a galaxy that ekes out a win over another by a nose (or, I suppose, a spiral arm).

On the other hand, there are times such records do tell us something important.

When I was working on the Hubble Space Telescope in the late 1990s, it was becoming common to find objects with a redshift of around 6.0 because the observatory was designed, in part, to be able to see extremely distant galaxies. Some objects were found that might be even more distant, but many were difficult to confirm. Over time, astronomers using Hubble and other telescopes managed to glimpse galaxies even farther away using clever techniques such as fortuitous gravitational lensing.

Then, in 2021, our capabilities took a giant leap with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope. Its infrared eye is more sensitive to extremely redshifted objects, and its huge 6.5-meter mirror outmatches Hubble’s smaller optics for gathering photons. Soon papers were published with claims of galaxies at redshifts of 10, 11 and even higher—and while many of those preliminary measurements wound up being spurious, several were ultimately confirmed out to redshifts greater than 14. This is one of those times that a record breaker is important: it’s telling us that we have a new way to observe the cosmos, which usually results in a new era of astronomical discovery.

For what it’s worth, at the time of this writing the current record holder is a very luminous red blob of a galaxy called MoM-z14 at a redshift of 14.44. But by the time you read this, who knows?

Those records have significant scientific meaning as well. For example, light travels very rapidly but not infinitely so. It takes billions of years for the light from these vastly removed galaxies to reach us, which means that the farther away they are, the earlier in the time line of the cosmos we see them. Any new record means we’ve added information about our knowledge of the early universe, and sometimes it even means we’re seeing the universe in a different stage of its development.

For example, when the cosmos was very young, it was opaque. But then, at some point, stars and supermassive black holes formed, spewing out energy and making it transparent. As we discover galaxies from that period, we can learn about the environment of space at that time, just a few hundred million years after the universe formed.

We also learn about galaxies themselves. Why do they shine so brightly at that age? They have supermassive black holes prodigiously feeding on infalling matter, but how did those black holes grow so huge so rapidly? The more distant a galaxy we find, the more data we have to unravel those mysteries.

Also, that database of distant objects can be used to learn about them in general. We might find that most distant galaxies have some average luminosity, with a few topping out a bit above that and none being brighter. That would tell us about the physics of how galaxies form, how they grow and how they emit light. If there is a single most brilliant distant galaxy, that could put firm limits on how they behave.

And there’s another record that will be difficult to break or even verify. When we look back far enough, we won’t see any more galaxies at all. Why not? Because they wouldn’t have formed yet! It took a few hundred million years for galaxies to collect themselves, with dark matter serving as gravitational scaffolding, allowing normal matter to gather and condense, collecting in colossal quantities that would eventually form nebulas, stars and planets. If we can see far enough into the distant cosmos, far enough into the past, we’ll be peering back in time to before those structures even existed.

To be fair, we already have done this; microwave telescopes have detected the fireball of the big bang, the leftover light from the original expansion of the universe that fills the sky as a gently glowing long-wavelength background (as distance records go, it’s at a redshift of about 1,000!). But there’s a several-hundred-million-year gap between that moment and the time at which galaxies first started popping up, and we know very little about it. Every record breaker we find squeezes that boundary a little tighter.

The universe is lovely, dark and deep, but with our powerful telescopes and clever brains, we keep pushing farther into it. For that, I welcome every new record that falls. At this point in our search, each one that’s broken is a footstep into new astronomical territory.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.