“It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” — Abraham Maslow, 1966

Microservices provide many benefits for building business services, such as independent tools, technologies, languages, release cycles, and full control over your dependencies. However, microservices aren’t the solution for every problem. As Mr. Maslow observed, if we limit our tool choices, we end up using less-than-ideal methods for fixing our problems. In this article, we’ll take a look at streaming SQL, so you can expand your toolbox with another option for solving your business problems. But first, how does it differ from a regular (batch) SQL query? …

“It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” — Abraham Maslow, 1966

Microservices provide many benefits for building business services, such as independent tools, technologies, languages, release cycles, and full control over your dependencies. However, microservices aren’t the solution for every problem. As Mr. Maslow observed, if we limit our tool choices, we end up using less-than-ideal methods for fixing our problems. In this article, we’ll take a look at streaming SQL, so you can expand your toolbox with another option for solving your business problems. But first, how does it differ from a regular (batch) SQL query?

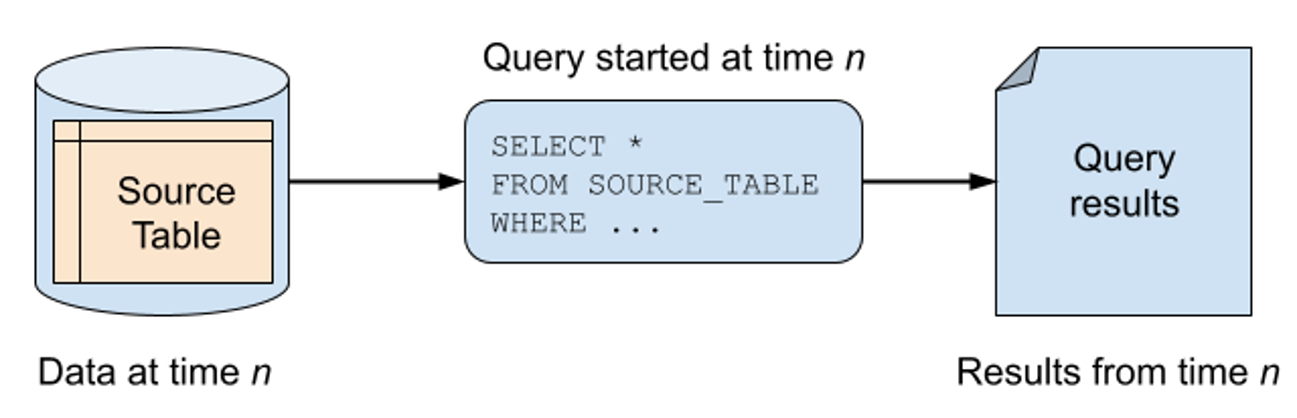

SQL queries on a traditional database (e.g. Postgres) are bounded queries, operating over the finite set of data within the database. The bounded data includes whatever was present at the point in time of the query’s execution. Any modifications to the data set occurring after the query execution are not included in the final results. Instead, you would need to issue another query to include that new data.

A bounded SQL query on a database table.

Confluent

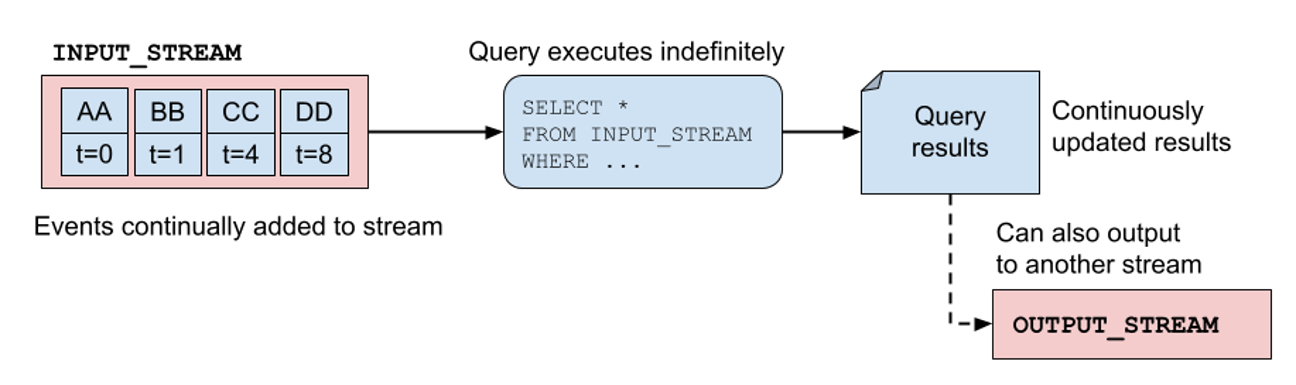

In contrast, a streaming SQL query operates on an unbounded data set—most commonly one or more event streams. In this model, the streaming SQL engine consumes events from the stream(s) one at a time, ordering them according to timestamps and offsets. The streaming SQL query also runs indefinitely, processing events as they arrive at the inputs, updating state stores, computing results, and even outputting events to downstream streams.

An unbounded SQL query on an event stream.

Confluent

Apache Flink is an excellent example of a streaming SQL solution. Under the hood is a layered streaming framework that provides low-level building blocks, a DataStream API, a higher level Table API, and at the top-most level of abstraction, a streaming SQL API. Note that Flink’s SQL streaming syntax may vary from other SQL streaming syntaxes, since there is no universally agreed upon streaming SQL syntax. While some SQL streaming services may use ANSI standard SQL, others (including Flink) add their own syntactical variations for their streaming frameworks.

There are several key benefits for building services with streaming SQL. For one, you gain access to the powerful streaming frameworks without having to familiarize yourself with the deeper underlying syntax. Secondly, you get to offload all of the tricky parts of streaming to the framework including repartitioning data, rebalancing workloads, and recovering from failures. Third, you gain the freedom to write your streaming logic in SQL instead of the framework’s domain-specific language. Many of the full-featured streaming frameworks (like Apache Kafka Streams and Flink) are written to run on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and offer limited support for other languages.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that Flink uses the TABLE type as a fundamental data primitive, as evidenced by the SQL layer built on top of the Table API in this four-layer Flink API diagram. Flink uses both streams and tables as part of its data primitives, enabling you to materialize a stream into a table and similarly turn a table back into a stream by appending the table updates to an output stream. Visit the official documentation to learn more.

Let’s shift gears now to look at a few common patterns of streaming SQL use, to get an idea of where it really shines.

Pattern 1: Integrating with AI and machine learning

First on the list, streaming SQL supports direct integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) models, directly from your SQL code. Accessing an AI or ML model through streaming SQL is easier than ever. Given the emergence of AI as a contender for many business workloads, streaming SQL gives you the capability to utilize that model in an event-driven manner, without having to spin up, run, and manage a dedicated microservice. This pattern works similarly to the user-defined function (UDF) pattern: You create the model, register it for use, and then call it inline in your SQL query.

The Flink documentation goes into greater detail on how you’d hook up a model:

CREATE MODEL sentiment_analysis_model

INPUT (text STRING COMMENT 'Input text for sentiment analysis')

OUTPUT (sentiment STRING COMMENT 'Predicted sentiment (positive/negative/neutral/mixed)')

COMMENT 'A model for sentiment analysis of text'

WITH (

'provider' = 'openai',

'endpoint' = 'https://api.openai.com/v1/chat/completions',

'api-key' = '<YOUR KEY>',

'model'='gpt-3.5-turbo',

'system-prompt' = 'Classify the text below into one of the following labels: [positive, negative, neutral, mixed]. Output only the label.'

);

Source: Flink Examples

The model declaration is effectively a bunch of wiring and configurations that enable you to use the model in your streaming SQL code. For example, you can use this model declaration to evaluate sentiments about the body of text contained within the event. Note that ML_PREDICT requires both the specific model name used and the text parameter:

INSERT INTO my_sentiment_results

SELECT text, sentiment

FROM input_event_stream, LATERAL TABLE(ML_PREDICT('sentiment_analysis_model', text));

Pattern 2: Bespoke business logic as functions

While streaming SQL offers many functions natively, it’s simply not possible to include everything into the language syntax. This is where user-defined functions come in—they’re functions, defined by the user (you), that your program can execute from the SQL statements. UDFs can call external systems and create side effects that aren’t supported by the core SQL syntax. You define the UDF by implementing the function code in a standalone file, then upload it to the streaming SQL service before you run your SQL statement.

Let’s take a look at a Flink example.

// Declare the UDF in a separate java file

import org.apache.flink.table.api.*;

import org.apache.flink.table.functions.ScalarFunction;

import static org.apache.flink.table.api.Expressions.*;

//Returns 2 for high risk, 1 for normal risk, 0 for low risk.

public static class DefaultRiskUDF extends ScalarFunction {

public Integer eval(Integer debt,

Integer interest_basis_points,

Integer annual_repayment,

Integer timespan_in_years) throws Exception {

int computed_debt = debt;

for (int i = 0; i < timespan_in_years; i++) {

computed_debt = computed_debt +

(computed_debt *

interest_basis_points / 10000)

- annual_repayment;

}

if ( computed_debt >= debt )

return 2;

else if ( computed_debt < debt && computed_debt > debt / 2)

return 1;

else

return 0;

}

Next, you’ll need to compile the Java file into a JAR file and upload it to a location that is accessible by your streaming SQL framework. Once the JAR is loaded, you’ll need to register it with the framework, and then you can use it in your streaming SQL statements. The following gives a very brief example of registration and invocation syntax.

-- Register the function.

CREATE FUNCTION DefaultRiskUDF

AS 'com.namespace.SubstringUDF'

USING JAR '<path-to-jar>';

-- Invoke the function to compute the risk of:

-- 100k debt over 15 years, 4% interest rate (400 basis points), and a 10k annual repayment rate

SELECT UserId, DefaultRiskUDF(100000, 400, 10000, 15) AS RiskRating

FROM UserFinances

WHERE RiskRating >= 1;

This UDF lets us compute the risk that a borrower may default on a loan, returning 0 and 1 for low and normal risk respectively, and a value of 2 for high-risk borrowers or accounts at risk. Though this UDF is a pretty simple and contrived example, you can do far more complex operations using almost anything within the standard Java libraries. You won’t have to build a whole microservice just to get some functionality that isn’t in your streaming SQL solution. You can just upload whatever’s missing and call it directly inline from your code.

Pattern 3: Basic filters, aggregations, and joins

This pattern takes a step back to the basic (but powerful) functions built right into the streaming SQL framework. A popular use case for streaming SQL is that of simple filtering, where you keep all records that meet a criteria and discard the rest. The following shows a SQL filter that only returns records where total_price > 10.00, which you can then output to a table of results or into a stream as a sequence of events.

SELECT *

FROM orders

WHERE total_price > 10.00;

Windowing and aggregations are another powerful set of components for streaming SQL. In this security example, we’re counting how many times a given user has attempted to log in within a one-minute tumbling window (you can also use other window types, like sliding or session).

SELECT

COUNT(user_id) AS login_count,

TUMBLE_START(event_time, INTERVAL '1' MINUTE) AS window_start

FROM login_attempts

GROUP BY TUMBLE(event_time, INTERVAL '1' MINUTE);

Once you have how many login attempts a user has in the window, you can filter for a higher value (say > 10), triggering business logic inside a UDF to lock them out temporarily as an anti-hacking feature.

Finally, you can also join data from multiple streams together with just a few simple commands. Joining streams as streams (or as tables) is actually pretty challenging to do well without a streaming framework, particularly when accounting for fault tolerance, scalability, and performance. In this example, we’re joining Product data on Orders data with the product ID, returning an enriched Order + Product result.

SELECT * FROM Orders

INNER JOIN Product

ON Orders.productId = Product.id

Note that not all streaming frameworks (SQL or otherwise) support primary-to-foreign-key joins. Some only allow you to do primary-to-primary-key joins. Why? The short answer is that it can be quite challenging to implement these types of joins when accounting for fault tolerance, scalability, and performance. In fact, you should investigate how your streaming SQL framework handles joins, and if it can support both foreign and primary key joins, or simply just the latter.

So far we’ve covered some of the basic functions of streaming SQL, though currently the results from these queries aren’t powering anything more complex. With these queries as they stand, you would effectively just be outputting them into another event stream for a downstream service to consume. That brings us to our next pattern, the sidecar.

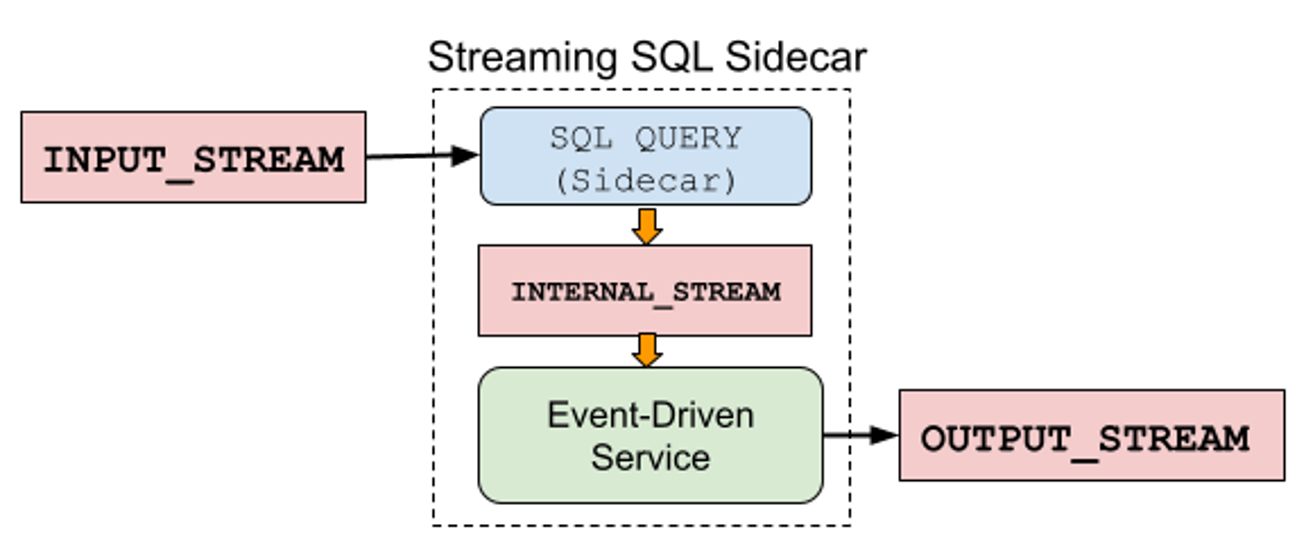

Pattern 4: Streaming SQL sidecar

The streaming SQL sidecar pattern enables you to leverage the functionality of a full featured stream processing engine, like Flink or Kafka Streams, without having to write your business logic in the same language. The streaming SQL component provides the rich stream processing functionality, like aggregations and joins, while the downstream application processes the resulting event stream in its own independent runtime.

Connecting the streaming SQL query to an event-driven service via an internal stream.

Confluent

In this example, INTERNAL_STREAM is a Kafka topic where the SQL sidecar writes its results. The event-driven service consumes the events from the INTERNAL_STREAM, processes them accordingly, and may even emit events to the OUTPUT_STREAM.

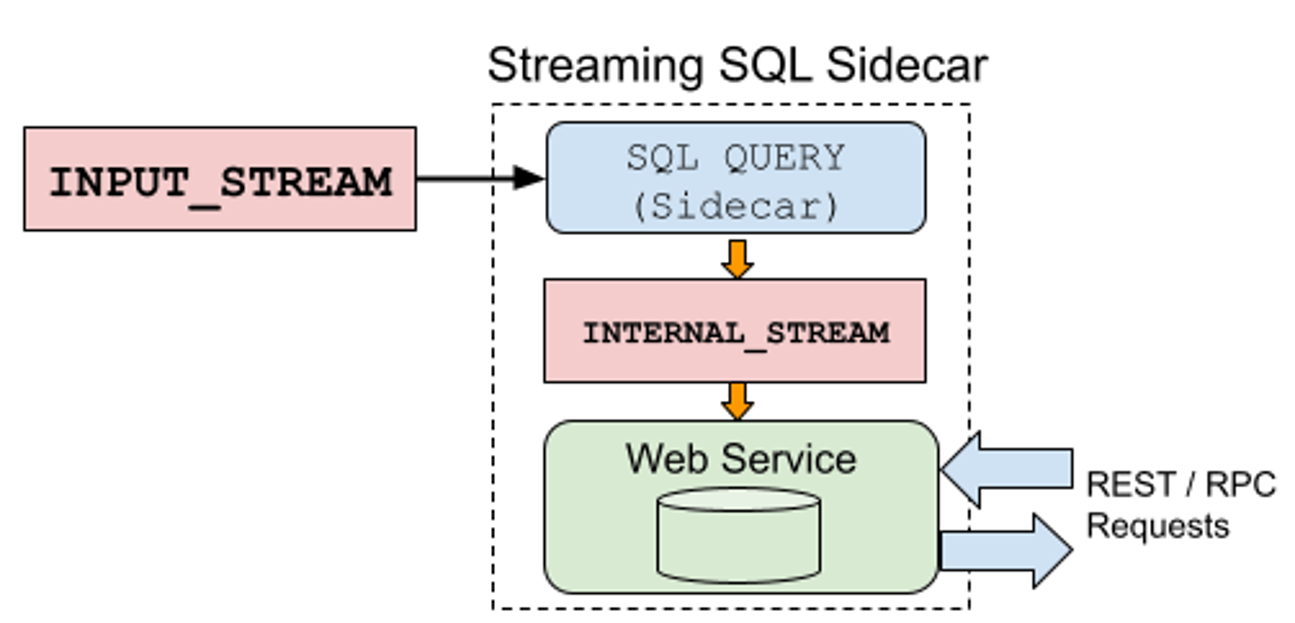

Another common use of the sidecar is to prepare data to serve using a web service to other applications. The consumer consumes from the INPUT_STREAM, processes the data, and makes it available for the web service to materialize into its own state store. From there, it can serve request/response queries from other services, such as REST and RPC requests.

Powering a web service to serve REST / RPC requests using the sidecar pattern.

Confluent

While the sidecar pattern gives you a lot of room for extra capabilities, it does require that you build, manage, and deploy the sidecar service alongside your SQL queries. A major benefit of this pattern is that you can rely on the streaming SQL functionality to handle the streaming transformations and logic without having to change your entire tech stack. Instead, you just plug the streaming SQL results into your existing tech stack, building your web services and other applications using the same tools that you always have.

Additional use cases

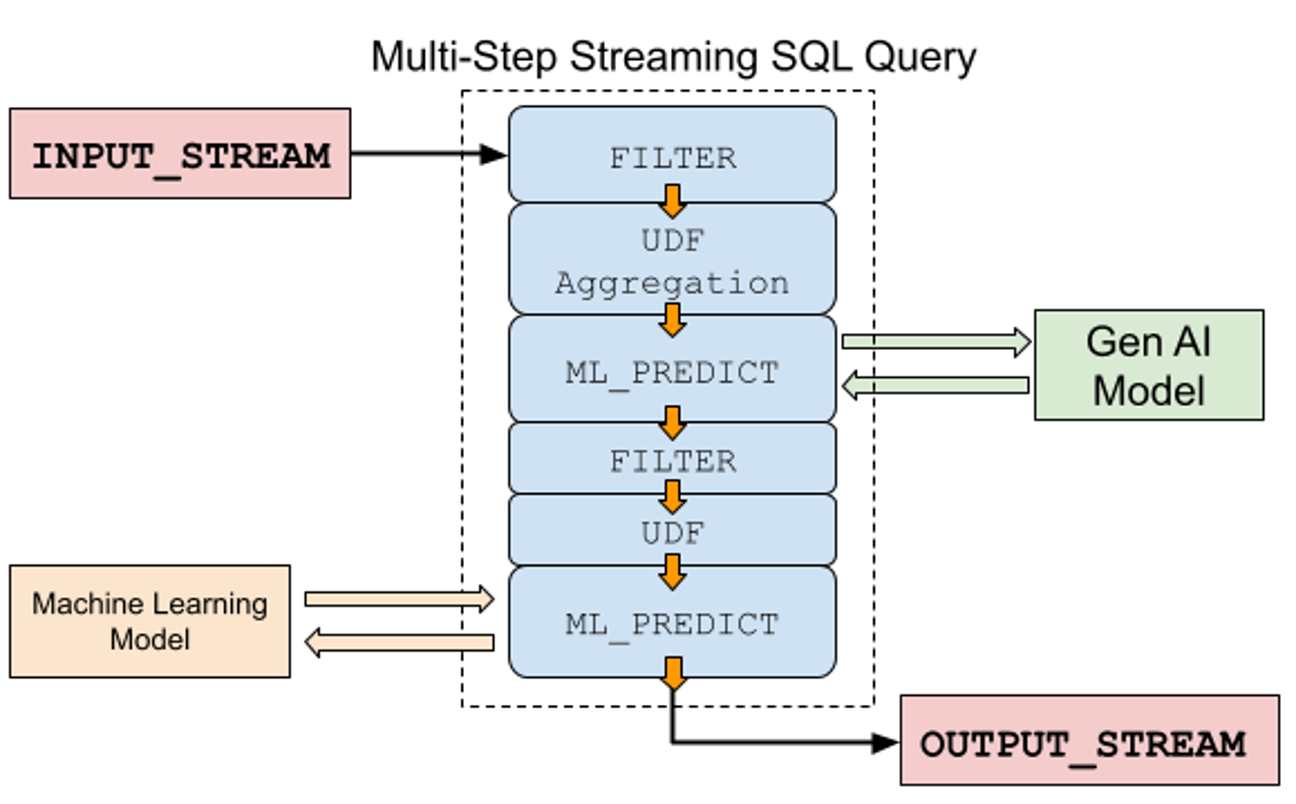

Each of these patterns shows operations in isolation, which may be enough for simpler applications. For more complex business requirements, there’s a good chance that you’re going to chain together multiple patterns, with each feeding its results into the next. For example, first you filter some data, then apply a UDF, then make a call to an ML or AI model using ML_PREDICT, as shown in the first half of the example below. The streaming SQL then filters the results from the first ML_PREDICT, applies a UDF, and then sends those results to a final ML model before writing to the OUTPUT_STREAM.

Chain multiple SQL streaming operations together for more complex use cases.

Confluent

Streaming SQL is predominantly offered as a serverless capability by numerous cloud vendors, billed as a quick and easy way to get streaming data services up and running. Between its built-in functions, UDFs, materialized results, and integrations with ML and AI models, streaming SQL has proven to be a worthy contender for consideration when building microservices.

—

New Tech Forum*** provides a venue for technology leaders—including vendors and other outside contributors—to explore and discuss emerging enterprise technology in unprecedented depth and breadth. The selection is subjective, based on our pick of the technologies we believe to be important and of greatest interest to InfoWorld readers. InfoWorld does not accept marketing collateral for publication and reserves the right to edit all contributed content. Send all ***inquiries to doug_dineley@foundryco.com.