This particular advertisement was the second announcement of an aging-up of a series originally published for YA readers in a little more than week. Just ten days earlier, Publishers Weekly ran a story about Sourcebooks updating and repackaging Claire LeGrand’s “Empirium” trilogy for adult readers. It is likely we’ll see another round …

This particular advertisement was the second announcement of an aging-up of a series originally published for YA readers in a little more than week. Just ten days earlier, Publishers Weekly ran a story about Sourcebooks updating and repackaging Claire LeGrand’s “Empirium” trilogy for adult readers. It is likely we’ll see another round of headlines and social media posts about this aging up when those editions arrive, even though the news is out there. Again: this is no secret.

Thinking practically, the aging up and repackaging of Bardugo’s duology makes sense. The new covers, stained edges, and updated character ages theoretically align with the readers who grew up with the series: if a 15-year-old picked up the books when they first released, they’d be 25 now. Why *not *try to repackage the magic for the same readers who found these books in their teens but who are now in their young adulthood? The covers are pretty dang awesome and seem to be playing to readers who love action-packed manga and anime.

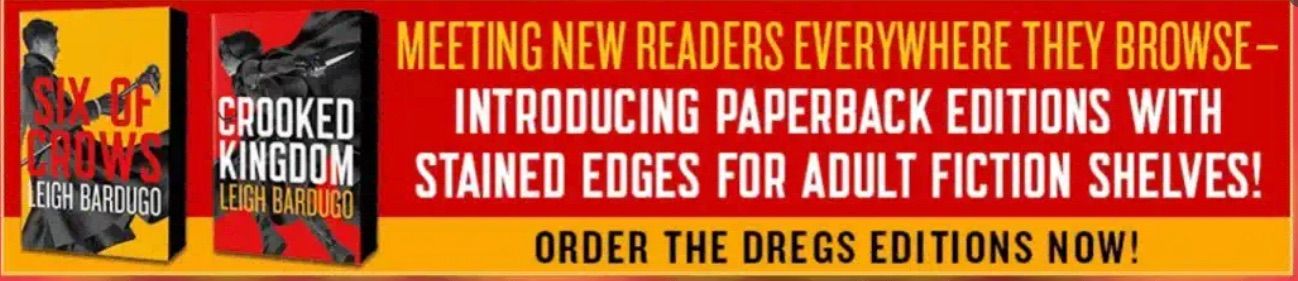

This might be why the adult repackaging is used to showcase the book’s bestseller status on the YA paperback list, even though that cover is not for the YA audience.

It’s harder to see that as the reason behind repackaging the LeGrand series. Perhaps that decision makes sense in context of the author finding success in the adult market with her Middlemist trilogy, a romantasy series compared to Sarah J. Maas’s *A Court of Thorns and Roses *juggernaut. By aging up a YA series, it’s easier to reach adult readers picking up the Middlemist books who are less propelled to pick up a series of teen readers.

Neither of these book series will be the only ones either being aged up or intentionally not being published for teen readers. They’re starting points for what seems like a feature of where we are with YA literature, rather than a bug. Publish the books for YA, see that it does better with adult audiences, then consider whether to repackage them for adult readers. This leaves teen readers with fewer options in their own category, of course.

But beyond the decrease in sales for YA books, there’s been a push for decades to launch a so-called “new adult” category of literature. When this push began, it came from the publishers. St. Martins Press sought to publish fiction “similar to YA” but that targeted and featured young adults in their 20s. It would take a few years to see this idea of “new adult” take off, and when it did, it was far from what the potential new category sought to do. It was nearly all contemporary romance novels featuring college or college-age main characters. These books also had plenty of steamy scenes and sex. There was little diversity in the titles on every sense of the word. It was romance but with a new, gimmicky title. The “new adult” trend sought to roll atop the waves of adults who composed more than half of the purchases of YA books but with titles that more aligned with their own age and life experiences.

“New adult” may never have manifested as originally hoped, but it hasn’t disappeared. The push for romantasy looks and feels like the “new adult” era and it, too, mirrors what we saw happen then. Sarah J. Mass’s massive bestselling series books, which straddle the line of YA and adult, are a model of what’s possible in reaching emerging adults, as well as now middle age adults who lived through the YA halcyon period. *Twilight *readers who picked up the first book in the series at age 15 are now 35, after all. But where the early 2010s “new adult” trend leaned hard into contemporary romance and published those books under new imprints or existing adult imprints, in the early/mid 2020s, we’ve gone full “romantasy,” including publishing those books at super speeds for the YA audience.

YA books are ostensibly written for teenagers. Reiterating this is important because it helps make sense of aging up titles, as well as putting more marketing and publicity behind things like romantasy, which are going to reach audiences with bigger pocketbooks: adults.

We know teenagers who want to read book for adults–including romances or romantasies with a bit of heat–are going to pick them up. This isn’t about shaming either them nor adults who enjoy these books. Sex belongs in YA books, too; it is one of the only safe places a young person can learn, experience, and think about sex in a no-pressure way (they can, after all, shut the book if it becomes too much for them!).

But this aging-up YA has also seen an aging-up of YA protagonists and an aging-up of how those books are being sold to teens. By raising the age of YA protagonists, it becomes more normalized to publish books featuring almost-legal or barely-legal main characters who have the kind of agency and experiences most actual teenagers do not.

University of Mississippi librarian Ally Watkins published research this summer that proves what many long-time YA readers and champions have thought: YA protagonists are getting older. She looked at 10 years’ worth of New York Times YA bestsellers and found that the characters were more likely to be at least 17 years old. While sticking to New York Times bestsellers is a limited data pool, it’s an important one, as it theoretically represents the most popular and most sold books.

Books with older teen characters simply sell better than those with younger teen characters. Knowing what we know about adults being the primary purchasers of YA books–research that doesn’t appear to have been updated in a decade–this means that adults are buying books written for teens with teen characters who are almost or fully adult.

Watkins’s assessment aligns with numerous assumptions about the why behind YA’s aging up. She says:

“It’s not really clear why protagonists are getting older, but I think many of the people who were reading YA back in the 2010s are still reading YA now,” Watkins said. “And that’s great—everybody should be able to read whatever they want.

“But I think when adult readers are influencing the market for younger people, that’s where there’s a problem.”

Alex Brown, librarian and award-winning writer-critic for Reactor, has tracked the age of YA protagonists in speculative fiction since 2023. Their lists, available here, have shown this very aging up trend as well. One important factor Brown notes is that even finding out how old the main character in YA is has gotten more challenging over the years. What used to be right on the jacket description is now buried in the story itself.

It takes *work *to know if the teen in the story is 14 or if they’re 19.1

“At least in science fiction, fantasy, and horror, in previous years there were usually half a dozen or so 15-year-olds, and a couple 14-year-olds, with most characters 16-18. But this year it’s a couple 14-16-year-olds and 19-year-olds, but almost everyone else is 17-18,” they said. “I’m losing younger teens who have nowhere to age up to from middle grade, as well as older teens who are re-reading middle grade favorites because they can’t find what they want in YA. Teens of all ages who want content and genre variety – such as mystery, adventure, and humor – are being left out because almost everything now is romantasy or has romance as a major plot point.”

But it’s not just the ages of YA protagonists going up. So, too, is the marketing itself. It’s utilizing more and more language that’s common in selling adult books, as opposed to teen books. We’re no longer talking about “cute” or “sweet” romance stories.

YA romances now have spice, they have heat, and they crackle with the kind of intensity hardly representative of the teen experience. Do teens have sex? Absolutely. Though, they’re having less of it than before–about 30% of high schoolers have engaged in intercourse. But judging by the descriptions and blurbs on books being sold as YA, teen sex is wild, abundant, and really good.

The November 16, 2025, New York Times YA bestseller list has three romantasy titles boasting about the heat within them.

“Sexy” is used in the author blurb for the book’s listing and on its cover for Bitten.

While “sexy” isn’t on the cover for Thorn Season–likely because this is a special edition–the pitch uses it.

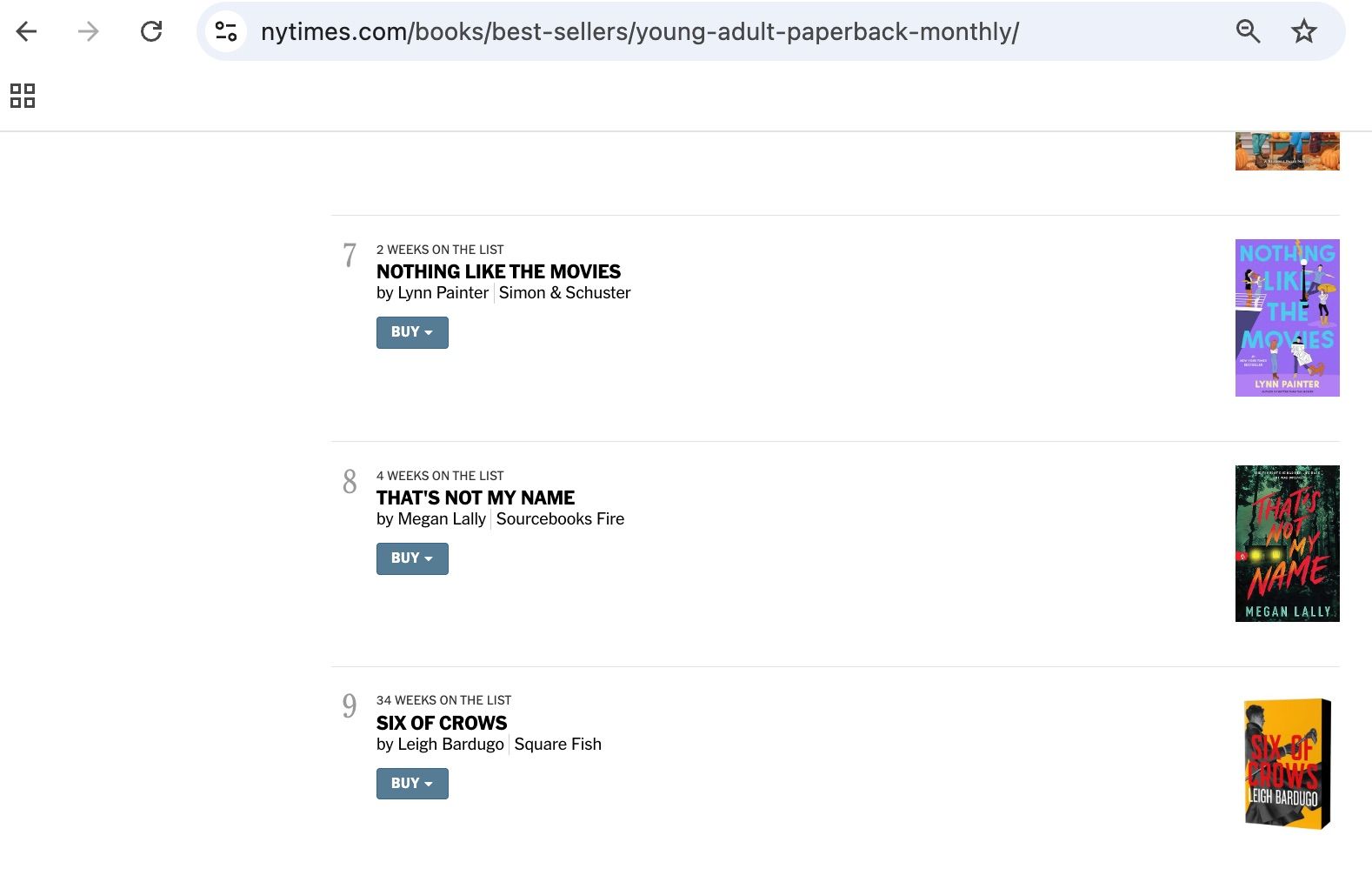

As for Heartless Hunter, this one is “steamy,” and “sizzling” per the author blurbs.

Pitches sent to YA gatekeepers aren’t much better. In fact, there are cases where the sexification of these books is played even harder because these pitches are going to adults directly.

The Gravewood by Kelly Andrews, being published for teens next spring by Scholastic, includes the phrase “making everyone feel horny” as part of its pitch.

Look for “sizzling chemistry” and “simmering tension” in *The Roommate Arrangement *by Samantha Markum’s January release.

These are but five examples of many, and they’re not intended to shame those working on copy. Again, too: teens read spicy books if that’s their thing, but those books are published for adult audiences. Why is it now that such marketing language is being used to sell books that are categorized as YA and, presumably, for a teen audience?

One answer seems to be that instead of trying to extract romantasy from YA and moving it into “new adult,” publishers are pumping more romantasy and more older teens into YA with hopes of capturing the money adults spend on these books.

Aging up YA books is a serious problem not only for teen readers who have fewer places to turn for books written for them. It’s not only a serious problem for adults who are looking for stories featuring younger adult characters in adult relationships and scenarios.

It’s a mega problem in an era of unrepentant book bans.

How can library workers defend their collections from attacks when the books being sold and marketed as for teen readers are using the language suited for adult books? Where and how can library workers defend their collections from accusations of being “inappropriate” for teen readers when books that were published *for *teen readers are now being repackaged for adult audiences?

This should be grounds for pause and consideration–library workers are already under enough pressure doing their job that then defending the confusing decisions made by publishers is not only unfair, it’s cruel. Library workers are put in the position to either quietly censor or defend a YA book being pitched as “steamy” and “sexy” with a 19-year-old protagonist as appropriate for their school library.

That’s a hell of a tightrope to walk, especially when library workers just want to get their teens excited about reading.

There are no clear answers here, just as there are no clear nor easy solutions. But we’ve got to really unpack the wheres, hows, and whys of today’s YA category. It’s shrinking in terms of what it’s offering while simultaneously squeezing young readers out of the books meant to engage and entertain them. Teens are being pushed out of a category among the few in publishing that has really worked to showcase better diversity and inclusion after calls for that necessary representation came loud and clear with We Need Diverse Books. They’re being ignored in a category that captures all that is exciting, scary, fun, sad, humorous, angering, and adventurous about such a small period of time in a person’s life: their adolescence.

“YA used to be where you could find some of the most creative and diverse stories. That was what lured in a lot of adults, like me, who wanted more representation than we were finding in adult literature. This was especially true for YA science fiction, fantasy, and horror,” says Brown. “But with the colonization of adults into YA, the diversity is getting pushed out or flattened. For example, romantasy might feature BIPOC characters, but the romance is typically cisallohet. It feels like we’re getting less representation now than previous years. I suspect it’s part of the larger social backlash to the summer of 2020. There is still incredible and diverse work happening in YA, but it also feels like we’re losing ground. Romantasy didn’t cause the problem – aging up YA has been an issue ever since publishers decided to target adult readers – but it’s not helping either.”

Making money is crucial for the sustainability of publishing. But why is it that YA, once a moneymaker *because of *how well it represented a tremendous range of teen experiences and stories, is now so focused on a few types of stories and a few types of characters that do not represent the core audience of the category?

As teens grow up, they have books meant to engage their adult interests and sensibilities. But if literature meant for teens disappears, where and how are they ever expected to fall in love with books, reading, and stories in the first place?

- None of this is to overlook that there are many great YA books centering younger teens, to be clear. But even “younger” YA books are themselves complicated, given the history of how often this ask of YA has been code for “clean” books–a subtle means of censorship. ↩︎