The JavaScript ecosystem spent much of 2025 responding to a sustained run of supply chain attacks, but it was the multi-wave Shai-Hulud campaign that ultimately reset expectations for what large-scale, automated compromise looks like. By the end of the year, organizations with JavaScript-heavy infrastructure were no longer treating supply chain malware as an edge case, but as an operational risk that could spread faster than human review.

Now, npm says it is preparing its next major response: staged publishing, a new release model designed to introduce deliberate friction into package publication, alongside expanded work on trusted publishing and identity-based workflows. The [announcement](https://github.blog/security/supply-chain…

The JavaScript ecosystem spent much of 2025 responding to a sustained run of supply chain attacks, but it was the multi-wave Shai-Hulud campaign that ultimately reset expectations for what large-scale, automated compromise looks like. By the end of the year, organizations with JavaScript-heavy infrastructure were no longer treating supply chain malware as an edge case, but as an operational risk that could spread faster than human review.

Now, npm says it is preparing its next major response: staged publishing, a new release model designed to introduce deliberate friction into package publication, alongside expanded work on trusted publishing and identity-based workflows. The announcement follows a rocky migration away from classic npm tokens, a transition that tightened security controls but also exposed how fragile and inconsistent many real-world publishing setups still are.

How npm Is Responding After Shai-Hulud#

Shai-Hulud was one of several supply chain campaigns in 2025 that illustrated how quickly attackers adapt to maintainer workflows. Across incidents, compromised credentials and malicious lifecycle scripts combined with CI automation to scale impact beyond individual packages.

In response, npm says it is working toward staged publishing, a model that introduces a review window before a package release becomes publicly available. Under the proposal, publishes would require explicit, MFA-verified approval from package owners during that staging period, giving maintainers a chance to catch unintended or malicious changes before they propagate downstream.

Staged publishing introduces a registry-level review step before packages become publicly available, adding an explicit checkpoint to a publication process that has historically been optimized for speed and automation.

Alongside staged publishing, npm says it is accelerating work on bulk onboarding for OIDC-based trusted publishing and expanding support for additional CI providers beyond GitHub Actions and GitLab. Together, these changes are meant to give maintainers more control over how and when packages are released, especially in automated environments.

The Aftermath of Classic Token Revocation#

The staged publishing announcement lands against the backdrop of one of the most disruptive npm changes in recent memory: the removal of classic tokens.

In early November, npm disabled classic token creation. On December 9, remaining classic tokens were permanently revoked, replaced by a mix of short-lived session tokens for local use and granular access tokens for automation. CLI support for managing granular tokens shipped the same day, along with new defaults enforcing 2FA on newly created packages.

The security intent was clear. Classic tokens were long-lived, widely reused, and frequently harvested during supply chain incidents. But the rollout placed a disproportionate burden on maintainers responsible for dozens or hundreds of packages, particularly those operating outside the narrow set of CI platforms supported by trusted publishing.

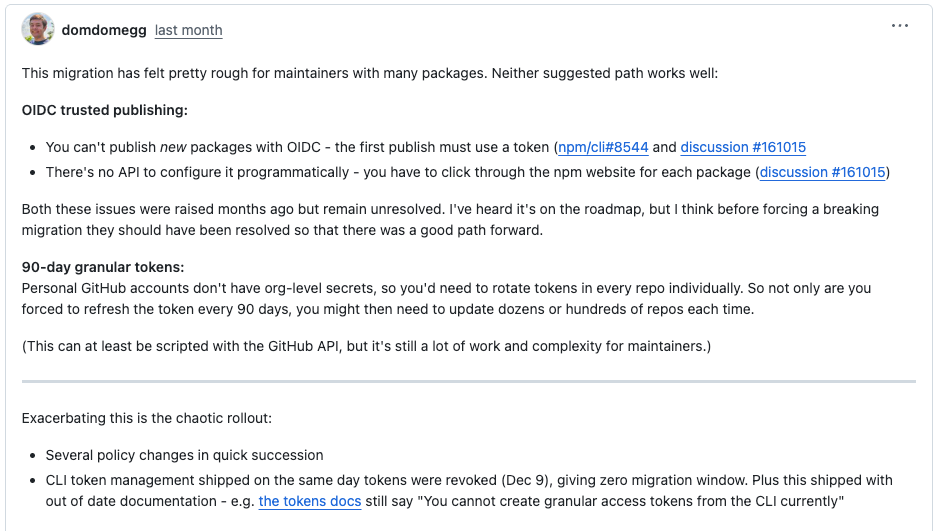

This transition raised more fundamental concerns about whether the available paths forward were workable at scale. Adam Jones, commenting under the GitHub handle ‘domdomegg’, described the migration as especially difficult for teams managing many packages.

Jones contends that neither of npm’s recommended paths fully addressed the realities of large-scale maintenance. OIDC trusted publishing, he noted, still cannot be used to publish new packages, requires manual configuration through the npm website on a per-package basis, and lacks an API for bulk setup. Those limitations had been raised months earlier but remained unresolved when classic tokens were revoked.

The alternative, short-lived granular tokens, created a different set of scaling problems. Because personal GitHub accounts do not support organization-level secrets, Jones wrote, maintainers often need to rotate tokens across individual repositories. For projects spanning dozens or hundreds of packages, that turns routine token rotation into ongoing, repo-by-repo maintenance, even when partially automated.

Jones also pointed to the rollout itself as a source of additional strain. Multiple policy changes landed in quick succession, with CLI support for granular token management shipping on the same day classic tokens were revoked. That left maintainers with little migration window, compounded by documentation that still reflected older tooling behavior.

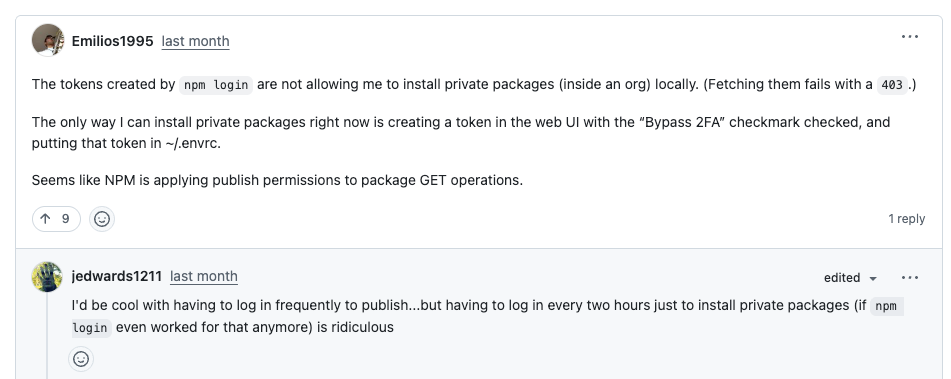

Confusion over which tokens were affected, unclear error messages, documentation drift, and unexpected authentication failures left many maintainers scrambling to diagnose broken pipelines. In some cases, users reported being prompted to re-authenticate every two hours just to install private packages, while others struggled to publish despite having valid tokens and successful logins.

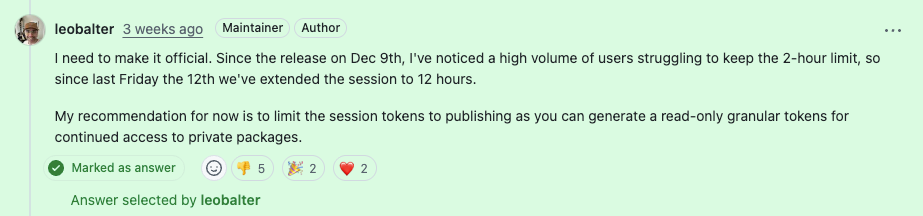

After widespread complaints, npm quietly extended session token lifetimes from two hours to twelve. “Since the release on Dec 9th, I’ve noticed a high volume of users struggling to keep the 2-hour limit,” npm maintainer Leo Balter commented in response to maintainers’ feedback. “Since last Friday the 12th we’ve extended the session to 12 hours.”

The adjustment helped, but it also made clear that tightening credential policy alone does not automatically make publishing workflows safer or easier to use.

Trusted Publishing and Its Current Limits#

GitHub and npm have positioned OIDC-based trusted publishing as the long-term replacement for token-based CI publishing. By removing long-lived secrets from build environments, the approach is intended to reduce the impact of credential theft in automated release pipelines.

In its current form, however, trusted publishing applies to a limited set of use cases. Support is restricted to a small number of CI providers, it cannot be used for the first publish of a new package, and it does not yet offer enforcement mechanisms such as mandatory 2FA at publish time. Those constraints have led maintainer groups to caution against treating trusted publishing as a universal upgrade, particularly for high-impact or critical packages.

Wes Todd, a longtime JavaScript maintainer involved in OpenJS security efforts, warned that “gaps in design and implementation with the new OIDC Trusted Publisher workflows leave maintainers open to novel and increasingly difficult to detect gaps in their publishing setups.” In its guidance, the OpenJS Foundation stopped short of recommending trusted publishing for critical projects, instead urging teams to align publishing controls with their risk profile and release model.

GitHub maintainers have said that expanded trusted publishing support and additional CI integrations are on the roadmap, but those changes have not yet landed, leaving the current limitations in place.

Beyond Credentials: Calls for Anomaly Detection#

For some maintainers, the focus on tokens misses the larger lesson of 2025’s attacks. In a post titled "How GitHub Could Secure npm," ESLint creator and longtime JavaScript maintainer Nicholas C. Zakas argued that npm’s response has over-indexed on credential security while neglecting registry-side detection.

Drawing an analogy to the credit card industry, Zakas argued that compromised credentials are inevitable, and that ecosystems need systems that can detect anomalous behavior even after an attacker has valid access. Suggestions included flagging publishes from unusual locations, restricting lifecycle script additions to major version bumps, and requiring additional verification when release behavior deviates from historical patterns.

Rather than preventing every compromise, Zakas framed these measures as a way to reduce how long malicious updates can circulate before they are detected.

Staged Publishing as a Registry Control#

Seen alongside those arguments, staged publishing addresses a different part of the problem. Instead of focusing on how credentials are issued or protected, it introduces a registry-level pause at publish time, when changes transition from a maintainer’s control into the broader ecosystem.

By adding a review window before packages go live, staged publishing could limit the speed at which compromised releases propagate, even when valid credentials are used. How effective that model proves to be will depend on details that have yet to be finalized, including how it interacts with CI automation, how approvals scale for large organizations, and whether it becomes an opt-in safeguard or a default expectation.

Taken together, the events of 2025 suggest that no single control is sufficient on its own. Credential hardening, trusted publishing, anomaly detection, and publication guardrails each address different failure modes. npm’s challenge now is not just shipping new security features, but integrating them in ways that reflect how open source software is actually built, released, and maintained at scale.