Abstract

Ammonia-oxidizing archaea are the most abundant chemolithoautotrophs in the ocean and are assumed to dominate carbon fixation below the sunlit surface layer. However, the supply of reduced nitrogen delivered from the surface in sinking particulate organic matter is insufficient to support the amount of nitrification required to sustain measured carbon fixation rates in the dark ocean. Here we attempt to reconcile this observed discrepancy by quantifying the contribution of ammonia oxidizers to dark carbon fixation in the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean. We used phenylacetylene—a specific inhibitor of the ammonia monooxygenase enzyme—to selectively inhibit ammonia oxidizers in samples collected throughout the water column (60–600 m depth). We show that, des…

Abstract

Ammonia-oxidizing archaea are the most abundant chemolithoautotrophs in the ocean and are assumed to dominate carbon fixation below the sunlit surface layer. However, the supply of reduced nitrogen delivered from the surface in sinking particulate organic matter is insufficient to support the amount of nitrification required to sustain measured carbon fixation rates in the dark ocean. Here we attempt to reconcile this observed discrepancy by quantifying the contribution of ammonia oxidizers to dark carbon fixation in the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean. We used phenylacetylene—a specific inhibitor of the ammonia monooxygenase enzyme—to selectively inhibit ammonia oxidizers in samples collected throughout the water column (60–600 m depth). We show that, despite their high abundances, ammonia oxidizers contribute only a small fraction to dark carbon fixation, accounting for 4–25% of the total depth-integrated rates in the eastern tropical Pacific. The highest contributions were observed within the upper mesopelagic zone (120–175 m depth), where ammonia oxidation could account for ~50% of dark carbon fixation at some stations. Our results challenge the current view that carbon fixation in the dark ocean is primarily sustained by nitrification and suggest that other microbial metabolisms, including heterotrophy, might play a larger role than previously assumed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Phytoplankton-driven primary production is one of the most important biological processes converting dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) into organic matter, forming the base of the marine food web1. While most of the DIC fixation in the surface ocean is fuelled by light energy, non-photosynthetic DIC fixation (‘dark DIC fixation’) has been proposed to contribute substantially to the biological uptake of DIC in the ocean2,3, possibly increasing global ocean primary production estimates by up to 22% (refs. 4,5). In surface waters, dark DIC fixation has primarily been associated with the activities of heterotrophic bacteria6,7, which can incorporate DIC into biomass via various carboxylation reactions involved in central metabolic functions such as C assimilation, anaplerosis and/or redox-balancing8,9.

Below the sunlit surface layer, the downward flux of particulate organic material is considered to be the main source of organic C sustaining the dark ocean’s heterotrophic food web10. However, current estimates point to a mismatch between organic matter consumption and supply in the deep ocean11,12, implying that additional sources of organic C are required to reconcile the C budget in the mesopelagic zone (defined here as below the euphotic zone to 1,000 m depth)13,14. DIC fixation rates can be substantial in the dark ocean13,15 and are often comparable in magnitude to microbial heterotrophic activity13,16,17. In aphotic waters, DIC fixation has largely been attributed to the activities of chemolithoautotrophic bacteria and archaea that use the energy released from oxidizing reduced compounds to fuel a variety of inorganic C fixation pathways13,18,19,20. Chemolithoautotrophic production is a source of particulate organic C that could contribute substantially to the microbial heterotrophic C demand in the dark ocean13,15,21. However, the activities of chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms are typically not well accounted for in mesopelagic C budgets22,23. An improved understanding of microbial processes in the mesopelagic zone is essential to better predict C export and sequestration, particularly under future climate change scenarios24,25.

Organic matter remineralization releases ammonium26, which is the primary energy source for chemolithoautotrophy in most parts of the global ocean18. Consequently, nitrification (the microbial oxidation of ammonia (NH3) to nitrite (NO2−) and further to nitrate (NO3−)) is expected to be tightly linked to dark DIC fixation. However, dark DIC fixation and nitrification are not routinely measured on oceanographic expeditions—particularly not in combination—making it impossible to accurately infer such a relationship. Empirical conversion factors obtained from pure culture studies are often used to estimate dark DIC fixation rates from nitrification rates27,28,29 and vice versa13,30. Measurements of DIC fixation in the deep ocean are on average one order of magnitude higher than could be supported by ammonium supplied by the sinking flux of particulate organic nitrogen (N) according to estimates of global ocean N export18,27,28. Multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain this large discrepancy, including: (1) unaccounted sources of ammonium to the deep ocean; (2) energy sources other than ammonia that support chemolithoautotrophy; and (3) heterotrophic microorganisms being a major contributor to dark DIC fixation14. However, direct evidence supporting any of these scenarios is thus far lacking.

In this study we established a methodological framework to specifically inhibit ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in ocean samples. We then quantified the fraction of dark DIC fixation fuelled by ammonia oxidation throughout the water column of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Finally, we explored the relationships between dark DIC fixation, ammonia oxidation and heterotrophic production. The results of this study help to reconcile the observed discrepancies between N supply and DIC fixation at depth, and advance our understanding of microbial processes in the dark ocean.

Environmental context

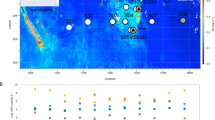

We sampled the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean spanning 35° N to 10° S during two oceanographic sampling campaigns (Fig. 1a). Sampling stations (Stns) included regions of varying productivity, from productive coastal waters (Stns 1 and 3) to the equatorial upwelling region (Stn 10) and to oligotrophic offshore stations in the eastern tropical North Pacific (ETNP; Stns 6, 12 and 15) and South Pacific (ETSP; Stns 5 and 7). A thick oxygen-deficient zone (ODZ; O2 ≤ 10 µM) was present at most stations, with the narrowest ODZ of ~50 m found at the equatorial station (Extended Data Fig. 1). We observed pronounced subsurface chlorophyll maxima at all offshore stations (Fig. 1b) and secondary chlorophyll maxima at the two northernmost offshore ETNP stations (Stns 6 and 15). Ammonia oxidation rates ranged between 0.4 and 64 nM d−1, showed typical maxima close to the base of the euphotic zone and sharply declined below, except at the station closest to the coast (Stn 1), where ammonia oxidation rates remained comparably high in the mesopelagic zone (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1: Cruise tracks and environmental context.

a, Station map of cruises RR2104 (green) and AT50-10 (orange). Bathymetry data from ref. 58. b, Ammonia oxidation rates, chlorophyll a fluorescence (FL) and ammonium (NH4+) and nitrite (NO2−) concentrations at eight stations during cruises AT50-10 and RR2104. NO2− concentrations were not measured at Stn 15. For ammonia oxidation rates, the mean and s.d. (error bars) of three biological replicates are shown (b.d., below the calculated detection limit of the method). Note that the error bars for ammonia oxidation rates are often smaller than the symbols. The depth of the euphotic zone is indicated by the grey dashed horizontal lines.

Ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) of the Nitrosopumilaceae family were the main ammonia oxidizers at all stations and depths, comprising up to 23% of the microbial community (Fig. 2). AOA abundances were low in surface waters and sharply increased to ~107 cells l−1 close to the base of the euphotic zone, coincident with high ammonia oxidation rates and low to undetectable ammonium concentrations (Fig. 1b). Within the mesopelagic zone, AOA abundances remained relatively constant, except at anoxic depths (<1 µM O2), where their abundances declined substantially (for example, Stn 12 at 600 m depth). ‘Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus’ (water column A clade, WCA) was the dominant AOA genus in shallow waters, whereas members of the water column B (WCB) clade dominated below 100 m depth and were often the only ammonia oxidizers in the mesopelagic zone (Fig. 2). Nitrosopumilus 16S rRNA gene sequences were detected in shallow waters only at Stns 5 and 12. Abundances of ‘Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus’ showed a positive linear relationship with ammonia oxidation rates (R2 = 0.47, Supplementary Fig. 1a). In contrast, WCB clade abundances and ammonia oxidation rates were negatively related (R2 = 0.43, Supplementary Fig. 1b), suggesting that ‘Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus’ were the main contributors to ammonia oxidation at our study sites (Supplementary Results and Discussion).

Fig. 2: Nitrosopumilaceae abundances and community composition in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

Relative 16S rRNA gene abundances of different AOA clades are shown as a fraction of the total microbial community. Ca., Candidatus. Absolute Nitrosopumilaceae abundances were derived from quantitative PCR assays and are shown in black. Means and standard deviations from triplicate measurements are shown. The depth of the euphotic zone is indicated by the grey dashed horizontal lines.

Specific inhibition of ammonia oxidation by phenylacetylene

A reliable method for specifically inhibiting the activities of ammonia oxidizers in ocean samples is required to isolate their contribution to dark DIC fixation. Phenylacetylene has previously been shown to inhibit cultures of terrestrial bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidizers by irreversibly binding to the ammonia monooxygenase enzyme31, and is more practical for handling on oceanographic expeditions than the well-characterized inhibitor acetylene gas32. When applying inhibitors to complex microbial communities, it is crucial to evaluate and account for potential undesired effects on microbial community members other than the target organisms. We first determined the effective inhibitory concentration of phenylacetylene on the ammonia oxidation and DIC fixation activities of marine ammonia oxidizer cultures (≥5 µM, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Results and Discussion). We also evaluated off-target effects of phenylacetylene on other members of the microbial community at select stations and depths. Phenylacetylene is known to inhibit other monooxygenase enzymes, including soluble and particulate methane monooxygenases33. However, methane monooxygenases are only inhibited at effective concentrations that are 10–100 times higher33 and relative abundances of putative methanotrophs were negligible at our study sites (≤0.04%, Supplementary Table 1). Phenylacetylene must be dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) due to its low solubility in water, which could affect microbial activity. Furthermore, phenylacetylene could be used as an energy source to support heterotrophic growth. When 10 µM phenylacetylene was added to whole seawater, ammonia oxidation was completely inhibited, while nitrite oxidation and microbial heterotrophic production rates did not significantly differ from those measured in control incubations without phenylacetylene (Fig. 3a,b). We also confirmed that DMSO alone had no significant effect on microbial heterotrophic production and dark DIC fixation during the time frame of our experiments (Fig. 3b,c). Consequently, phenylacetylene seems to be an effective specific inhibitor of ammonia oxidation activity in the ocean and can be used to infer the contributions of ammonia oxidizers to dark DIC fixation rates (‘ammonia-fuelled dark DIC fixation’).

Fig. 3: Effect of phenylacetylene on rates of microbial processes in ocean samples.

a, Effect of 10 µM phenylacetylene additions (+PA) on ammonia (NH3) oxidation (top), nitrite (NO2−) oxidation (middle) and dark DIC fixation rates (bottom) at the indicated depths at Stns 1, 3 and 6 (left to right) during cruise RR2104. b,c, Comparison between additions of phenylacetylene (10 µM) dissolved in DMSO (0.01%) or DMSO alone (+DMSO) on microbial heterotrophic production (b) and dark DIC fixation rates (c) at the indicated depths at Stns 5 and 15 during cruise AT50-10, respectively. The mean and s.d. of three biological replicates are shown. *Significant difference between treatments (determined using one- or two-sided Student’s t-tests, P < 0.05). Details of the statistical analyses can be found in the Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

Total and ammonia-fuelled dark DIC fixation

We measured total dark DIC fixation rates throughout the water column of four stations, spanning the ETNP, ETSP and equatorial Pacific (Fig. 4). Dark DIC fixation rates decreased with depth from the euphotic zone to the upper mesopelagic zone (defined here as below the euphotic zone and above 200 m depth), with the highest rates of ~11 nM d−1 observed at 65 m (Stn 12) and 70 m (Stn 15) depth in the ETNP (Figs. 3c and 4). DIC fixation rates in the lower mesopelagic zone (≥200 m depth) ranged between 0.3 and 1.9 nM d−1, with slightly increased rates in anoxic waters (O2 < 1 µM) at Stns 5 and 12, possibly due to the activities of anaerobic chemolithoautotrophs34. Depth-integrated dark DIC fixation rates ranged between 0.2 mmol C m−2 d−1 and 0.9 mmol C m−2 d−1, which is considerably lower than the range of rates in the North Atlantic (1.8–3.2 mmol C m−2 d−1; ref. 13). Organic matter export from the euphotic zone is estimated to be higher in the North Atlantic35 than in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, leading to higher overall productivity that could explain these observed differences.

Fig. 4: Depth-resolved dark DIC fixation rates in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

Total dark DIC fixation rates are depicted in black and dark DIC fixation rates after phenylacetylene addition (+PA) in blue. The mean and s.d. of three biological replicates are shown unless otherwise stated. Error bars were omitted for four experiments (PA-inhibited treatment of Stn 5 at 200 m depth, Stn 5 at 300 m depth and Stn 10 at 200 m depth and the control treatment of Stn 12 at 65 m depth); only duplicate measurements were available for these experiments due to issues during sample processing. Oxygen concentration profiles are depicted by grey solid lines and the depth of the euphotic zone by grey dashed lines. Note that the scales on the x axes are different for the stations in each column. *Significant difference between treatments (determined using one-sided Student’s t-tests, P < 0.05). Details of the statistical analyses can be found in the Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

We also determined the contribution of ammonia oxidizers to total dark DIC fixation in the euphotic and mesopelagic zones. When phenylacetylene was added to incubation bottles, dark DIC fixation rates significantly decreased on average by 24% (s.d. = 9%, n = 7) in the euphotic zone and by 41% (s.d. = 8%, n = 7) in the upper mesopelagic zone (Figs. 3 and 4). However, no statistically significant degree of inhibition was observed in the majority of incubation experiments (n = 14, Fig. 4), suggesting minor contributions of ammonia oxidizers to dark DIC fixation throughout most of the water column. Ammonia oxidizers are inhibited by light36,37,38 and nitrification rates in the euphotic zone are typically low under in situ light conditions39,40,41. While our incubations were performed in the dark, thereby excluding acute light inhibition, AOA abundances were particularly low in surface waters (Fig. 2), potentially explaining their low contribution to dark DIC fixation within the euphotic zone. Surprisingly, however, despite their high abundances in the lower mesopelagic zone, none of the incubation experiments showed significant inhibition after the addition of phenylacetylene (n = 7), indicating that ammonia oxidizers did not play a significant role in dark DIC fixation at these depths at the tested stations. We hypothesize that this could partly be due to the thick ODZ observed at most of the stations (Extended Data Fig. 1), and the reliance of ammonia oxidation on O2 availability42. Alternatively, WCB clade AOA might rely on other as-yet unknown metabolisms to support their high abundances in the deep ocean (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Results and Discussion).

Overall, ammonia oxidation could account for only 4–25% of the depth-integrated dark DIC fixation rates in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean (Fig. 4). This implies that other microbial metabolisms contribute substantially to the cycling of inorganic C in the water column. Consequently, dark DIC fixation rates cannot be used to infer nitrification rates. In contrast, ammonia-fuelled dark DIC fixation rates could be inferred from ammonia oxidation rates if suitable conversion factors were available.

DIC fixation yields of ammonia oxidizers in the ocean

We aimed to better constrain DIC fixation yields (moles of C fixed per mole of N oxidized) of ammonia oxidizers in the ocean to improve conversion factors for biogeochemical models. Ammonia oxidation and the fraction of dark DIC fixation inhibited by phenylacetylene (ammonia-fuelled dark DIC fixation) showed a strong positive linear relationship (R2 = 0.68, Fig. 5a). The average DIC fixation yield derived from the slope of the regression was ~0.05, which is considerably lower than those for cultures of ‘Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus brevis’ U25 and Nitrosopumilus sp. CCS1 isolated from the North Pacific Ocean (mean ± s.d. = 0.09 ± 0.01; ref. 27). The lower observed DIC fixation yields of AOA in the ocean might suggest a lower metabolic efficiency compared with ideal culture conditions. Our yield calculations, which relied on measuring 15N-ammonium-derived ammonia oxidation rates, did not take into consideration the possible preferential utilization of organic N sources (for example, urea) over ammonium43, which could theoretically lead to even lower environmental DIC fixation yields. Substantial urea utilization in the presence of experimentally added ammonium has been observed in the northwestern Pacific Ocean44; however, the potential impacts on 15N-ammonium-derived ammonia oxidation rates across different ocean regions are yet to be determined.

Fig. 5: Relationships between dark DIC fixation, ammonia oxidation and heterotrophic production rates in the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean.

a, Linear relationship between ammonia oxidation rates and the fraction of dark DIC fixation inhibited by phenylacetylene. Ammonia-fuelled dark DIC fixation rates were calculated by subtracting phenylacetylene-inhibited measurements (n = 3) from non-inhibited measurements (n = 3); error bars show the propagated error using s.d. Only experiments for which significant differences between inhibited and non-inhibited treatments were observed were included (Supplementary Table 1). For ammonia oxidation rates, the mean and s.d. of three biological replicates are shown. b, Linear relationship between heterotrophic production and total dark DIC fixation rates. The mean and s.d. of three biological replicates are shown unless otherwise stated. Error bars were omitted from heterotrophic production measurements from Stn 12, for which only duplicate samples were taken. One data point (Stn 5, 200 m depth) was excluded due to unrealistically high heterotrophic production rates, possibly resulting from contamination or human error. The data points are colour coded by sample depth, with darker colours reflecting deeper depths. The two cruises are differentiated by symbol shape. Linear regression analysis was performed and the significance of the model fit (P < 0.05) was evaluated using F-statistic hypothesis testing. Details of the statistical analyses can be found in the Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

Although relatively low tracer additions (70–200 nM) were used in our study, the possible stimulation of ammonia oxidation is a relevant concern for rate measurements in the oligotrophic ocean and could lead to lower observed DIC fixation yields when measuring rates from separate incubation bottles (with DIC bottles not receiving corresponding additions of ammonium). This may have been the case on cruise AT50-10, where radioactivity safety protocols precluded combined rate measurements of nitrification and DIC fixation. In contrast, on cruise RR2104 13C-labelled bicarbonate was used to measure DIC fixation rates in more productive waters, allowing us to combine both measurements within the same incubation bottle. Even when considering only samples from cruise RR2104, the average DIC fixation yields (0.054) were identical to those calculated from all data points. We therefore consider the DIC fixation yields of ammonia oxidizers in this study to be realistic environmental estimates for the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean that can be used to inform theoretical models to better constrain the relationship between C and N fluxes in the dark ocean.

Additional metabolisms contributing to dark DIC fixation

Ammonia is considered to be the primary energy source fuelling water column chemolithoautotrophy18 due to the higher molar ratio of N in marine organic matter relative to other potential energy sources, such as reduced sulfur (S) and iron45,46. Ammonia oxidizers supply nitrite (NO2−) to nitrite oxidizers, and the two steps in the nitrification process are typically tightly coupled47. Consequently, the inhibition of ammonia oxidation probably also results in the indirect inhibition of nitrite oxidation in the absence of an alternative NO2− source. However, most of our stations were located in regions with pronounced ODZs, suggesting that NO2− could also be supplied via nitrate reduction48. We assessed nitrite oxidation rates at selected depths (Supplementary Fig. 3) and used the average DIC fixation yield of cultured marine nitrite oxidizers (0.036, ref. 27) to estimate their potential contributions to dark DIC fixation. We estimate that ammonia and nitrite oxidizers together could, on average, account for 70% (s.d. = 22%, n = 10) of dark DIC fixation in the upper mesopelagic zone, but only 36% (s.d. = 10%, n = 5) within the euphotic zone. However, nitrite oxidizers in the open ocean are phylogenetically only distantly related to cultured representatives20 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Given the lower DIC fixation yields observed for ammonia oxidation in the environment compared with those of cultured ammonia oxidizers (Fig. 5a; ref. 27), the contributions of nitrite oxidizers to dark DIC fixation could be substantially lower than estimated here.

The genomic potential for chemolithoautotrophy fuelled by sulfur oxidation is widespread in the dark ocean19,49,50, and putative sulfur oxidizers were present at all stations (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Results and Discussion). The organic S content of sinking particulate organic matter is ~17 times lower than the N content45, suggesting a very limited supply of reduced S to the dark ocean. Even when considering the higher DIC fixation yields of sulfide oxidizers (0.15–0.35; refs. 51,52) compared with ammonia oxidizers (0.05; Fig. 5a), we estimate that sulfur-fuelled chemolithoautotrophy could amount to only one-third of that of ammonia-fuelled chemolithoautotrophy.

Heterotrophic microorganisms may also contribute to dark DIC fixation in the ocean14,17,53, particularly in surface waters where the uptake of DIC by different heterotrophic taxa has previously been shown to be high (40–200 nM C d−1; ref. 54). A compilation of >700 microbial heterotrophic production and dark DIC fixation measurements from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans indicated a positive linear relationship between both processes (R2 = 0.45; ref. 14). We found a similar, yet stronger, relationship between microbial heterotrophic production and total dark DIC fixation in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean (R2 = 0.80; Fig. 5b). The sparse available data on heterotrophic DIC fixation suggest that 1–10% of C in bacterial biomass is derived from DIC assimilation55,56,57. When we assumed that heterotrophs incorporate 10% of their C as DIC, we could explain on average 30% (s.d. = 15%, n = 22) of the dark DIC fixation rates in the epi- and upper mesopelagic zones.

Implications for the dark ocean’s C budget

Our data confirm that ammonia oxidation is an important process in the upper mesopelagic zone, but we show that it contributes a much lower percentage of dark DIC fixation than previously assumed, amounting to a maximum of 25% of the depth-integrated rates in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. When including high-end estimates of nitrite- and sulfur-fuelled chemolithoautotrophy and heterotrophic DIC fixation, 36–111% of the depth-integrated dark DIC fixation rates could be explained (Table 1). Discrepancies remain, particularly within the euphotic zone, where the contributions of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers to total dark DIC fixation are comparably small, and in the lower mesopelagic zone (≥200 m depth), where the flux of particulate organic matter from the surface is often insufficient to provide the energy sources required to sustain measured dark DIC fixation rates at depth. Constraining the contributions of sulfur oxidizers and heterotrophs will be crucial to reconcile these observed discrepancies.

Our results improve our understanding of microbial processes in the dark ocean and offer insights into the main energy sources fuelling dark DIC fixation. Our findings have broad implications as they provide critical conversion factors for biogeochemical models of the mesopelagic C budget, which are essential to better predict the impact of future climate scenarios on the biological sequestration of C in the ocean.

Methods

Cruise track and dissolved nutrient analyses

Water samples were collected during two oceanographic cruises in the eastern tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean aboard the R/V Roger Revelle (cruise RR2104: 15–29 June 2021) and the R/V Atlantis (CliOMZ, cruise AT50-10: 2 May–9 June 2023) at a total of eight stations spanning 35° N to 10° S (Fig. 1a). On both cruises, hydrographic data were collected with an SBE-911plus conductivity, temperature, depth (CTD) sensor package (SeaBird Scientific) that was also equipped with a fluorometer (ECO, Seabird Scientific) and a Clark-type electrode oxygen sensor (SBE 43, SeaBird Scientific). Discrete water samples were collected using a rosette sampler equipped with 24 10 l Niskin bottles.

Ammonium (NH4+) concentrations were measured on board from unfiltered 40 ml seawater samples using the o-phthaldialdehyde derivatization method59 with the modifications suggested in ref. [60](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-025-01798-x#re